On View

At 96, the Sculptor Beverly Pepper Is Only Now Getting Credit for Using Cor-Ten Steel Way Before Richard Serra

At 96, Beverly Pepper is still making monumental sculptures.

When one thinks of an artist who works with massive, rusted Cor-ten steel, Richard Serra might be the first name to come to mind. But it was actually 96-year-old Beverly Pepper who was the first artist to work with the material, way back in 1964.

“I’m the first person—the first artist in America—to use Cor-Ten,” Pepper told the Smithsonian Archives of American Art’s oral history project in 2009. “US Steel said to me—because, you know, they liked me. I was this good-looking kid—’Beverly, why don’t you try this new material we have. It’s Cor-Ten.'”

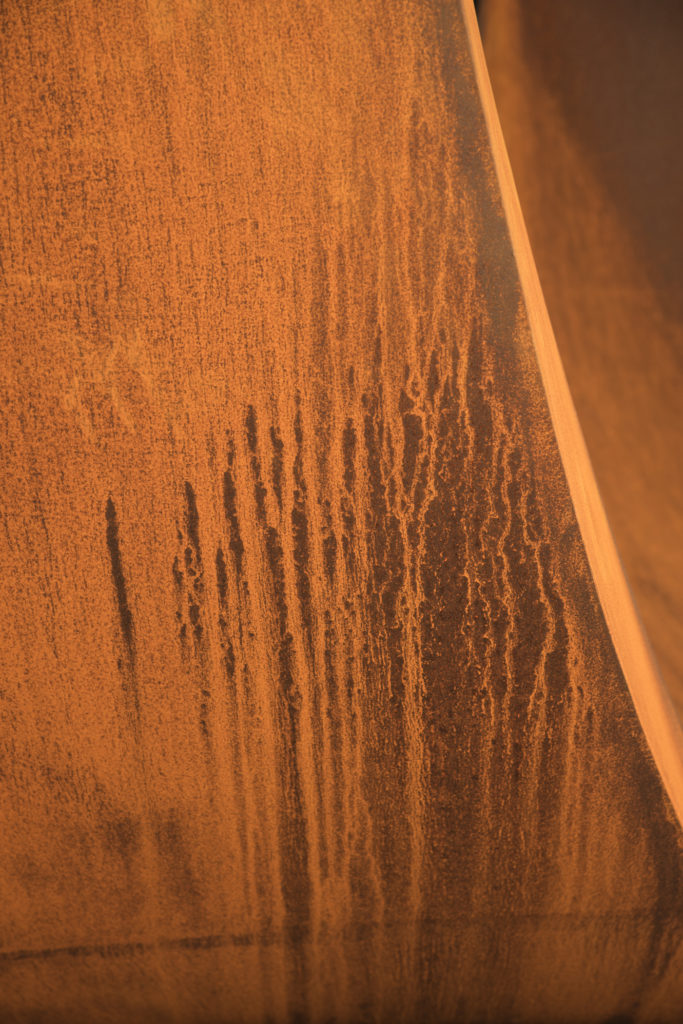

From this simple suggestion sprang a lifetime of work, monumental sculptures that are naturally weather-resistant, with surfaces that oxidize, turning to rich shades of reddish brown, a layer of rust that fends off corrosion and protects the material from moisture. The trademarked steel alloy material that soon became the staple of Pepper’s practice is at the heart of the artist’s new show in New York, “Beverly Pepper: Cor-Ten,” at Marlborough Contemporary through March 23.

The show highlights Pepper’s dynamic sculptural curves, powerful bands of metal that arc toward you, unbowed and unbreakable, each weighing as much as 6,000 pounds. The works are presented on artificial turf, as if outdoors, which is a typical setting for the artist.

“My sculptural language has developed and grown for sixty years,” Pepper told artnet News in an email. “Seeing, touching, and the physical sensory engagement is the way into my sculpture; my intention is that the meaning of my work rests in experiencing it.”

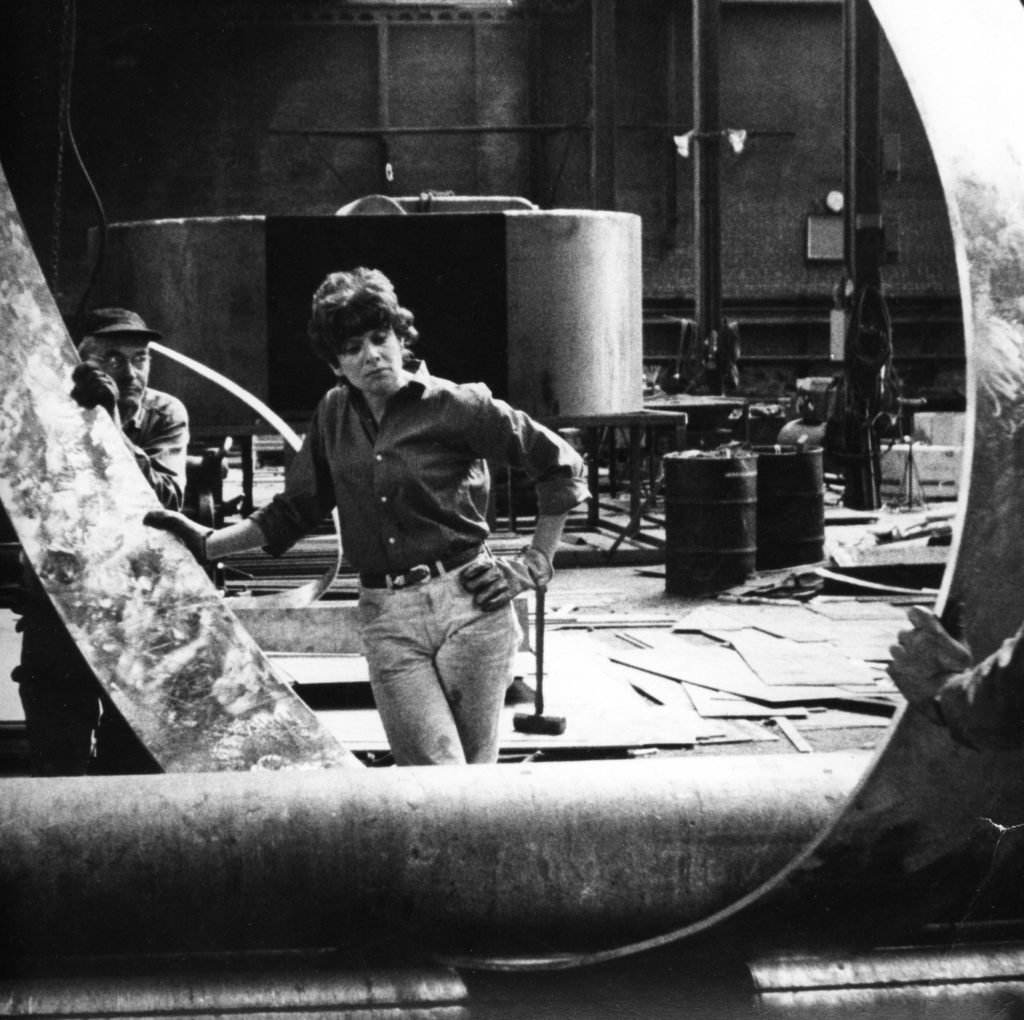

Beverly Pepper working in Spoleto, Italy (1962). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Pepper, who was born in Brooklyn in 1922, studied art at Pratt University. In her first year of school, she took a class in industrial design with Rowena Reed Kostellow, but the university decided that, as a woman, Pepper wasn’t capable of operating the machinery. So although those studies were cut short, the artist still credits that class with equipping her with the skills that would guide her work as a sculptor.

“It was heaven. It was like I came home,” Pepper recalled during the Smithsonian oral history. “Everything I know about—that I use to make sculpture—I learned in the class.”

Pepper was later invited to work in an Italian factory, where she began making large-scale metal works. “I’ve never been happier than I was when I was in a factory,” she said. Her invitation to work with Cor-Ten came while working at the US Steel factory in Conshohocken, Pennsylvania.

Beverly Pepper working at the Foundry in Italy (circa 1960s). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

The advantages of the material were immediately apparent. “Cor-Ten steel requires no painted or other sealed surface, giving her the opportunity to creates sculpture with stable natural oxidized surface finishes,” said Marlborough’s Dale Lanzone in an email. “Her latest works continue to demonstrate her unique ability to create sculptures that, in their ‘intense self absorption,’ seemingly exist both in and outside of historic time.”

Despite her advanced years, Pepper continues to work every day in her studio, a former airplane hangar in Italy. “Beverly rises early, works in the studio with her assistants, has a group lunch with assistants, then returns to the studio. Later in the afternoon, she works out with a physical trainer,” said Lanzone. Her goals are simply to “continue to work!”

Beverly Pepper, Helena (2014). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Pepper’s work is owned by institutions including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center, Paris’s Centre George Pompidou, and the Dallas Museum of Art, and she has been the subject of solo shows at the Brooklyn Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Art, and the Ara Pacis Museum in Rome. Nevertheless, Pepper isn’t as widely known as some of her peers, including Serra, David Smith, or Louise Bourgeois.

Since the 1950s, Pepper has lived largely in her adopted hometown of Todi, Italy, at a remove from the mainstream art world. But the time may at last be ripe for recognition. Another show of Pepper’s early work, from 1958 to 1967, opened last month in Los Angeles at Kayne Griffin Corcoran, and she’ll unveil the Beverly Pepper Sculpture Park in Italy this September.

Beverly Pepper working at the Iron factory (2012). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

“At 96 years of age, Beverly is her own force of nature with a very clear, singular artistic voice,” said Lanzone.

But she has had to make some adjustments over the years. For one thing, she no longer welds or uses grinding machines. “I have a very bad back,” she admitted back in 2009. “I’ve been working with those heavy materials for a long time.” As a result, there are “certain things I can’t do. But that’s fine because it leads me to do something else. Makes me invent another wheel, you see. Which is the interesting thing about it.”

See more photographs of Pepper and her work in the Marlborough Contemporary show below.

Beverly Pepper, Clodia Medea (2014). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Beverly Pepper, Clodia Medea (2014), detail. Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Beverly Pepper, My Circle (2008). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Beverly Pepper, My Circle (2008), detail. Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Beverly Pepper, Helena (2014), detail. Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Beverly Pepper, Medea (2014). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Beverly Pepper at the John Deere factory in Illinois (1980). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Beverly Pepper (1970). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Beverly Pepper working at a foundry in Italy. Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Beverly Pepper welding (1970). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

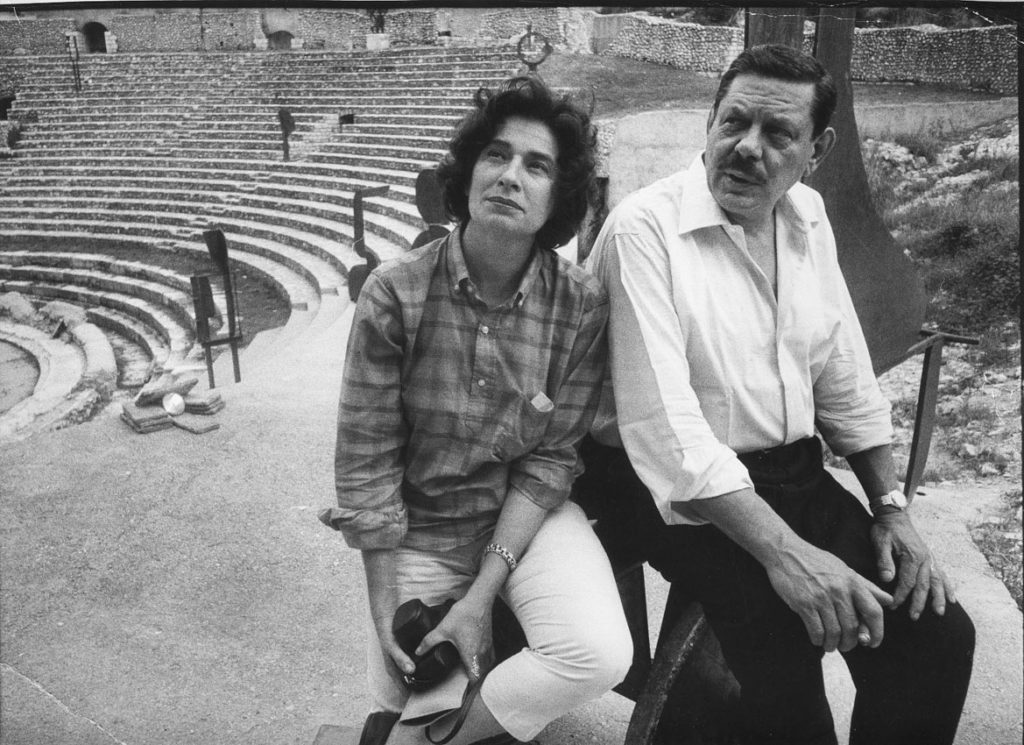

Beverly Pepper and David Smith in Spoleto (1962). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

Beverly Pepper working in the factory (2009). Photo ©Beverly Pepper, courtesy of Marlborough Contemporary, New York and London.

“Beverly Pepper: Cor-Ten” is on view at Marlborough Contemporary, 545 West 25th Street, February 23–March 23, 2019.

“Beverly Pepper: New Particles From the Sun” is on view at Kayne Griffin Corcoran, 1201 South La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, California, January 12–March 9, 2019.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

Article topics