People

Lutz Bacher, the Elusive Conceptual Artist Who Never Revealed Her Real Name, Face, or Age, Has Died

The mysterious, pseudonymous artist died of a heart attack on May 14, leaving behind precious few details of her life.

The pseudonymous artist Lutz Bacher died of a heart attack in New York City on May 14. Her conceptual work, known for defying categorization, encompassed photography, sound art, sculpture, video, and appropriation art, much of it exploring sexuality, power, and violence through politically charged juxtapositions of text and image.

News of Bacher’s passing was confirmed by the artist’s galleries, Greene Naftali in New York and Galerie Buchholz in Berlin, Cologne, and New York. “The impact and influence of her life and work is immeasurable,” Greene Naftali director Martha Fleming-Ives told artnet News. Her work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, among many other institutions.

Bacher kept her real name a secret, and the only photograph of the artist that appears to be available online, on the webpage for her 2018 solo showat the Fondation d’entreprise Galeries Lafayette in Paris, obscures her face.

The details of Bacher’s biography also remain a mystery, despite a career that spans more than 40 years. According to New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the artist was born in 1952. But a 2008 work, Bingo (Or the Year I Was Born), calls that into question by presenting a bingo card with numbers that light up at random. (Wikipedia lists her birth year as 1943.)

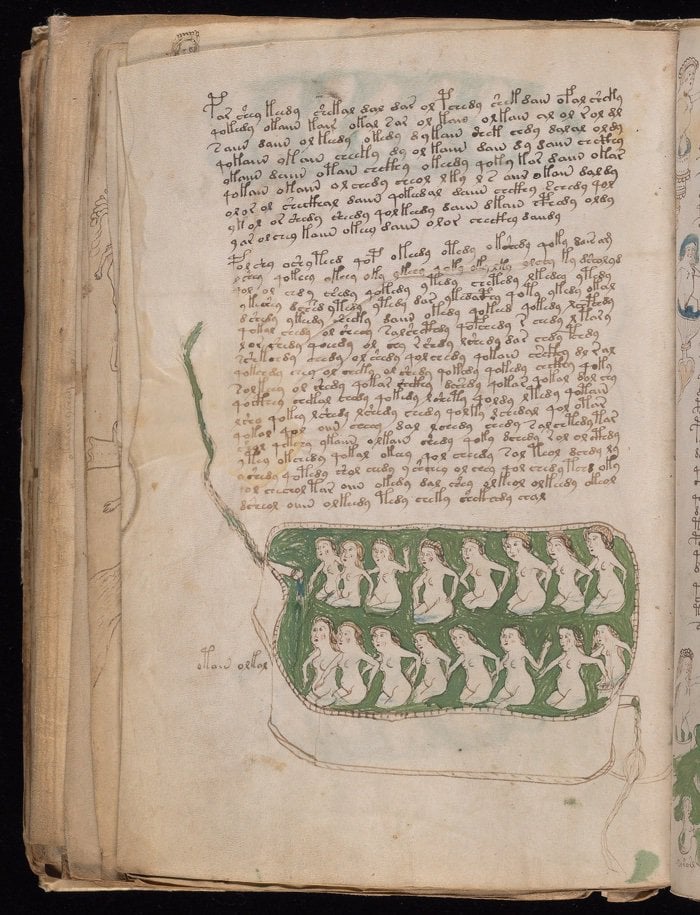

Lutz Bacher, Jokes (Groucho Marx) (1987-88). Photo courtesy of Galerie Buchholz.

Bacher moved to Berkeley, California, in the 1970s and called the Bay Area home for decades before relocating to New York sometime after 2013.

The artist was similarly evasive about her work, once releasing a recipe for butterscotch pudding in lieu of a press release for a 2008 exhibition at Ratio 3 in San Francisco—almost certainly delicious, but not particularly illuminating in terms of understanding the art. In 2012, Bacher published a book titled Do You Love Me?, based on extensive interviews with artists, curators, and others who knew her and whom she asked to describe her.

“[Bacher’s] approach has been constantly to shape-shift, deny her authorial signature, disperse like smoke,” wrote Martin Herbert in Art Review in 2015. “Recognizing the cult of personality that clings to artists, she’s made herself a personality in absentia, à la Warhol and Duchamp.… Recognizing up front that viewers never get a full picture, always inject their biases into whatever they see, Bacher doesn’t even try to present one; she offers something explicitly speckled with holes and gaps to occupy.”

Lutz Bacher, Do You Love Me? Photo courtesy of the artist.

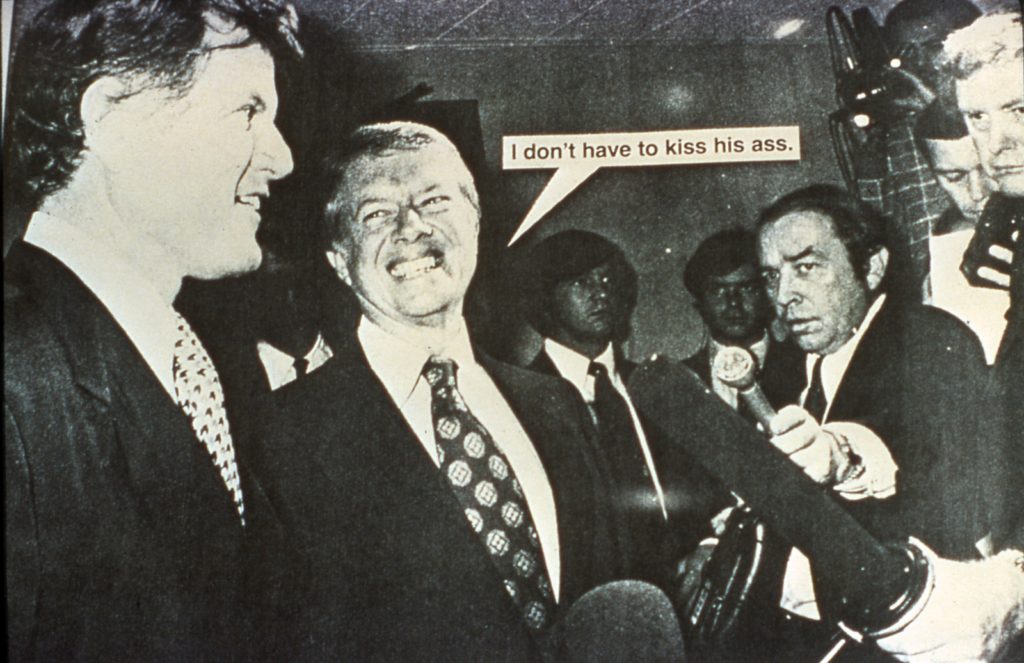

Often humorous and pointed, Bacher’s work includes her 1986 series “Sex With Strangers,” which featured enlarged photocopies of pornographic images, and “Jokers” (1985-87), which overlays off-color comments atop blown-up photos of celebrities and politicians, most of whom are white men.

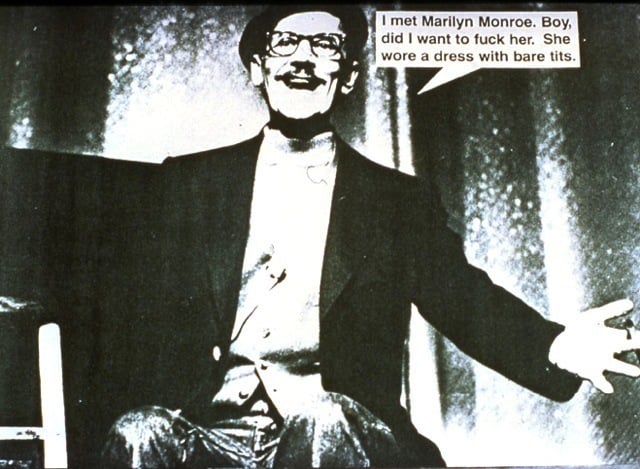

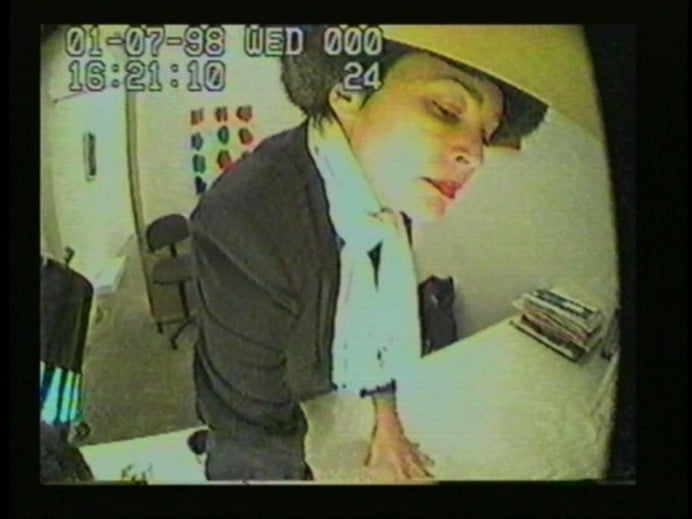

Lutz Bacher, Closed Circuit (1997-2000). Photo courtesy of MoMA PS1.

Over the years, Bacher’s New York gallery representation included Pat Hearn Gallery, Colin de Land’s American Fine Arts, Taxter and Spengemann, and Alex Zachary Peter Currie.

When Hearn, who died in 2000, was diagnosed with liver cancer, Bacher set up a surveillance camera in the gallery, capturing 1,200 hours of footage of the last years of the dealer’s life. The result was a 40-minute video, Closed Circuit.

Lutz Bacher, Magic Mountain (2015). Photo courtesy of MoMA PS1.

Bacher was the recipient of an Anonymous Was a Woman grant in 2002, and was included in the 2012 Whitney Biennial, where her piece Baseballs 2(2011) dumped hundreds of baseballs onto the museum’s fourth floor. A similarly show-stopping work, Magic Mountain (2015), filled a gallery with a massive pile of gray foam spikes in the “Greater New York” exhibition at MoMA PS1 in Queens in 2015. The museum had previously hosted Bacher’s first museum survey, “MY SECRET LIFE,” in 2009.

The artist’s last one-person gallery show, “Open the Kimono,” was in Cologne at Galerie Buchholz last fall. It featured Bacher’s recent series “Swingers,” in which she rephotographed personal ads from the back pages of vintage adult magazines, a precursor to today’s online dating.

Lutz Bacher, Carter/Kennedy (Kiss Ass) (1987). Photo courtesy of the artist.

“One always treads uncertain territory with Lutz Bacher, who has made a habit of elusiveness,” wrote Faye Hirsch in Art in America in 2015. “Yet suddenly her avoidance strategy feels like an effective defense against an art world in which understanding can be so easily monetized as PR or collecting points.”

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

Article topics