The Conceptual Argument for China’s Big Business in Fake Art

“Those who do not want to imitate anything, produce nothing,” said late, great Surrealist master, Salvador Dalí. Redolent of China’s ongoing challenges—and contrivances—surrounding appropriation, plagiarism and conceptualism in contemporary art, Dalí’s words are also relevant to an incident in China last month in which a white French artist effectively killed off the Chinese (and, significantly, already dead) alter ego he’d been hiding behind for a decade.

“On April 4th 2015, Tao Hongjing passed away in a mysterious construction site accident while conducting research for his next project,” read the press release for the artist’s recent exhibitions at Red Gate Gallery and Shun Gallery. All was not as it seemed, though, and on the eve of the show’s Beijing unveiling, the French ‘curator’ of this merry masquerade, Alexandre Ouairy, revealed that he and Tao Hongjing were, in fact, one and the same—and had been for the past decade.

“On April 4th 2015, Tao Hongjing passed away in a mysterious construction site accident while conducting research for his next project,” read the press release for the artist’s recent exhibitions at Red Gate Gallery and Shun Gallery. All was not as it seemed, though, and on the eve of the show’s Beijing unveiling, the French ‘curator’ of this merry masquerade, Alexandre Ouairy, revealed that he and Tao Hongjing were, in fact, one and the same—and had been for the past decade.

Forged artworks from China is big business. A cursory search of Chinese e-commerce site Alibaba quickly turns up copies of works by Yue Minjun and Zhang Xiaogang, all going for less than $500. Likely painted in one of China’s fabled artists villages, they’re convincing enough—when viewed on a laptop screen at least. (It’s worth pointing out that a majority of the canvases produced in these hives of industry—not to mention talent—are totally legit decorative pieces created without an acknowledged author, which likely hang in a hotel or model home near you.)

One such Chinese replica was hung in the hallowed hallways of Dulwich Picture Gallery in spring 2015, hidden there by American conceptual artist Doug Fishbone amidst the institution’s 270 displayed masterpieces. Called “Made in China,” the experiment raised issues surrounding the value we ascribe to art with regard to its authenticity and accomplishment. Apparently very impressive, perhaps the same talented copyist was responsible for an allegedly forged canvas by Geng Jianyi, Hairdressing 2, being withdrawn from China’s Poly Auction in October 2015 after the artist denied its authenticity.

Although it is unusual for forged works attributed to big-name contemporary artists to make it so far along the high-end selling process (the biggest challenge being that the artists themselves are very much alive, vocal, and vigilant), Chinese antiquities are notoriously mired in fakes. The problem has become almost farcical: In July 2015, the former chief librarian of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts admitted stealing more than 140 paintings from a gallery under his charge, replacing them with fakes he painted himself. Soon, however, Xiao Yuan noticed that his own fakes were disappearing from the gallery and being replaced by others, lending truth to the librarian’s defense: Everybody’s doing it.

One such Chinese replica was hung in the hallowed hallways of Dulwich Picture Gallery in spring 2015, hidden there by American conceptual artist Doug Fishbone amidst the institution’s 270 displayed masterpieces. Called “Made in China,” the experiment raised issues surrounding the value we ascribe to art with regard to its authenticity and accomplishment. Apparently very impressive, perhaps the same talented copyist was responsible for an allegedly forged canvas by Geng Jianyi, Hairdressing 2, being withdrawn from China’s Poly Auction in October 2015 after the artist denied its authenticity.

Although it is unusual for forged works attributed to big-name contemporary artists to make it so far along the high-end selling process (the biggest challenge being that the artists themselves are very much alive, vocal, and vigilant), Chinese antiquities are notoriously mired in fakes. The problem has become almost farcical: In July 2015, the former chief librarian of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts admitted stealing more than 140 paintings from a gallery under his charge, replacing them with fakes he painted himself. Soon, however, Xiao Yuan noticed that his own fakes were disappearing from the gallery and being replaced by others, lending truth to the librarian’s defense: Everybody’s doing it.

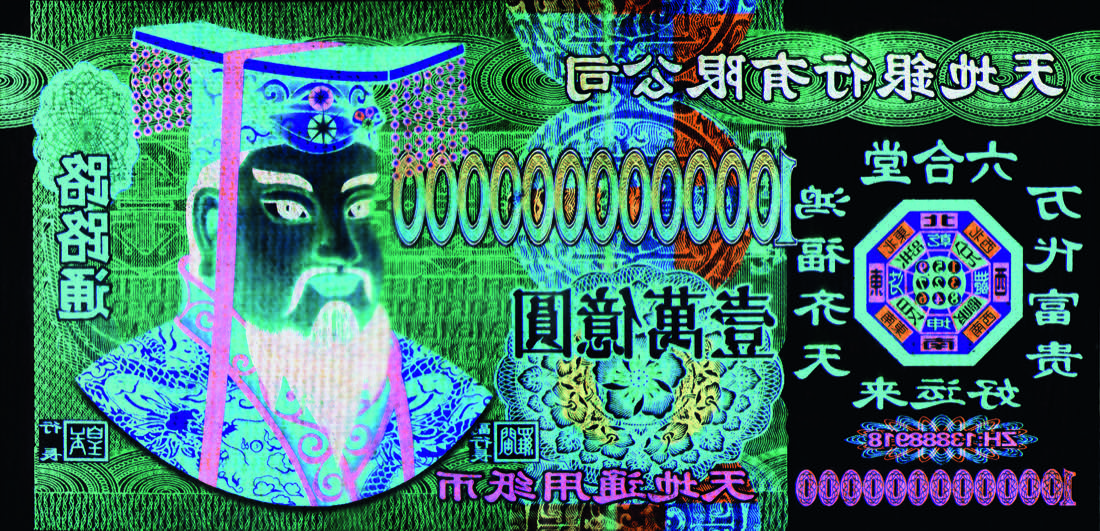

Daft as it may sound, Xiao Yuan’s explanation strikes a chord with bonafide Chinese contemporary artists. Take Xu Zhen, for example, for whom an ongoing and very deliberate blurring of authenticity, identity, and value attribution is a core component of his associated practices. To date, those identities include Xu Zhen’s art corporation MadeIn Company (launched 2009), MadeIn Company’s “brand” Xu Zhen (launched in 2013), and the man himself (born in 1977).

Is differentiating between the three personas necessary, particularly for buyers? “Collectors are more understanding and open and fun than we might perceive them,” says Xu Zhen, suitably evasively. With ambiguity as a hallmark, the artist’s mash-ups of cultural symbols and identifiers include 2010’s Seeing One’s Own Eyes at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery, comprising objects made in China by a fictional group of Middle Eastern artists.

Whether conceptual caper, duplicity, or simply selective amplification of certain truths over others, Chinese artists’ identities have long been integral to their value. In the breakneck ascent to Chinese contemporary art’s zenith in the West—those frothy early 2000s—things were palpably indiscriminate… just so long as the work was Chinese. And as an insatiable appetite for signature Cynical Realism and Political Pop grew, so too did a kind of appropriation of the emblems of Chinese contemporary art: Zeng Fanzhi-esque masks, for example, or Mao Jackets à la Sui Jianguo. Mimicking—not necessarily copying—the show-stealers of the time, they continued the dialogue around contemporary Chinese art, ultimately saturating a certain scene to the point of cliché.

Is differentiating between the three personas necessary, particularly for buyers? “Collectors are more understanding and open and fun than we might perceive them,” says Xu Zhen, suitably evasively. With ambiguity as a hallmark, the artist’s mash-ups of cultural symbols and identifiers include 2010’s Seeing One’s Own Eyes at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery, comprising objects made in China by a fictional group of Middle Eastern artists.

Whether conceptual caper, duplicity, or simply selective amplification of certain truths over others, Chinese artists’ identities have long been integral to their value. In the breakneck ascent to Chinese contemporary art’s zenith in the West—those frothy early 2000s—things were palpably indiscriminate… just so long as the work was Chinese. And as an insatiable appetite for signature Cynical Realism and Political Pop grew, so too did a kind of appropriation of the emblems of Chinese contemporary art: Zeng Fanzhi-esque masks, for example, or Mao Jackets à la Sui Jianguo. Mimicking—not necessarily copying—the show-stealers of the time, they continued the dialogue around contemporary Chinese art, ultimately saturating a certain scene to the point of cliché.

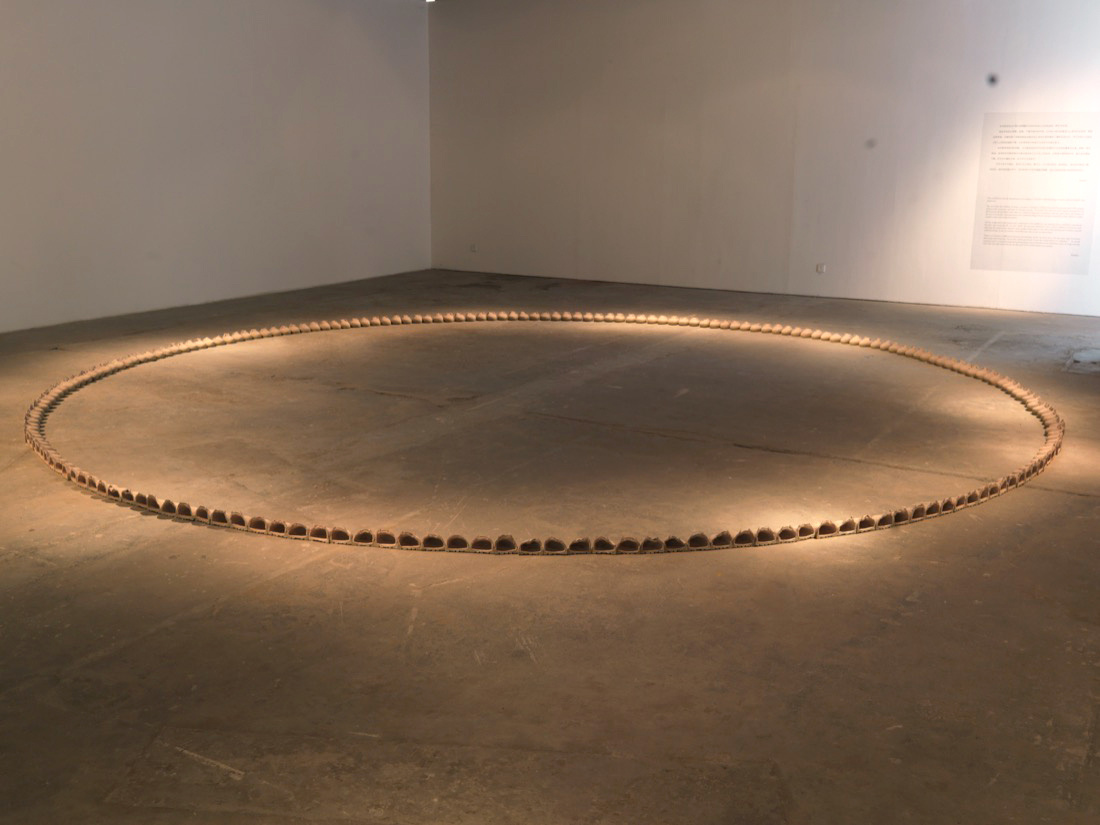

While the fervor in the West may have cooled, the gauntlet has been firmly passed to a new breed of young, monied Chinese collectors, flaunting their buying prowess at auction and at art fairs internationally. Much like Xu Zhen’s parodying of the commodification of art in China, an upcoming solo by Elmgreen and Dragset slated for January 23rd–April 17th at Beijing’s UCCA will take the form of a faux art fair, complete with art fair-style booths.

Both present an uneasy satire on the now fetishized affinity between art, China, and money. It’s an ironic juncture indeed when China’s fake fairs, forged art, stylistic plagiarism, and deliberate plays on the “Made in China” stereotype reveal the country’s contemporary issues more than some of their “legitimate” peers. Above all, the likes of Xu Zhen, those anonymous Alibaba artists, and perhaps even Tao Hongjing raise questions of value, and where the monetary worth of art lies. In China, itself a mecca for fake handbags, fake food, and in the case of Zaha Hadid’s Wangjing Soho (a Beijing building complex which was subsequently copied in another Chinese city), even fake architecture, “fakeness” today carries connotations of an ironic authenticity.

As China’s arts ecology continues to mature, today’s frenzied buying will inevitably stabilize, and in doing so, put the market for knock-offs squarely in its place. Until then, a murky world of simulacrum, intellectual property (and sometimes out-and-out fraud) does precisely what art should be doing: it reflects contemporary culture, and outs taboos.

—Frances Arnold

Both present an uneasy satire on the now fetishized affinity between art, China, and money. It’s an ironic juncture indeed when China’s fake fairs, forged art, stylistic plagiarism, and deliberate plays on the “Made in China” stereotype reveal the country’s contemporary issues more than some of their “legitimate” peers. Above all, the likes of Xu Zhen, those anonymous Alibaba artists, and perhaps even Tao Hongjing raise questions of value, and where the monetary worth of art lies. In China, itself a mecca for fake handbags, fake food, and in the case of Zaha Hadid’s Wangjing Soho (a Beijing building complex which was subsequently copied in another Chinese city), even fake architecture, “fakeness” today carries connotations of an ironic authenticity.

As China’s arts ecology continues to mature, today’s frenzied buying will inevitably stabilize, and in doing so, put the market for knock-offs squarely in its place. Until then, a murky world of simulacrum, intellectual property (and sometimes out-and-out fraud) does precisely what art should be doing: it reflects contemporary culture, and outs taboos.

—Frances Arnold