Art World

New Book Reveals the Greatest Rivalries in Modern Art

They say the strongest steel is forged in the hottest flame.

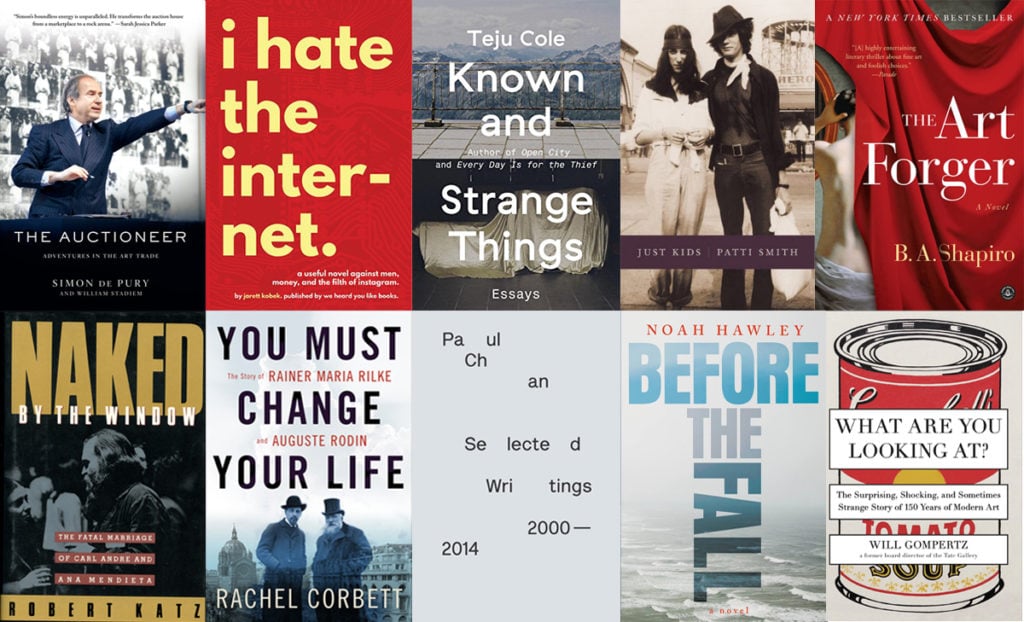

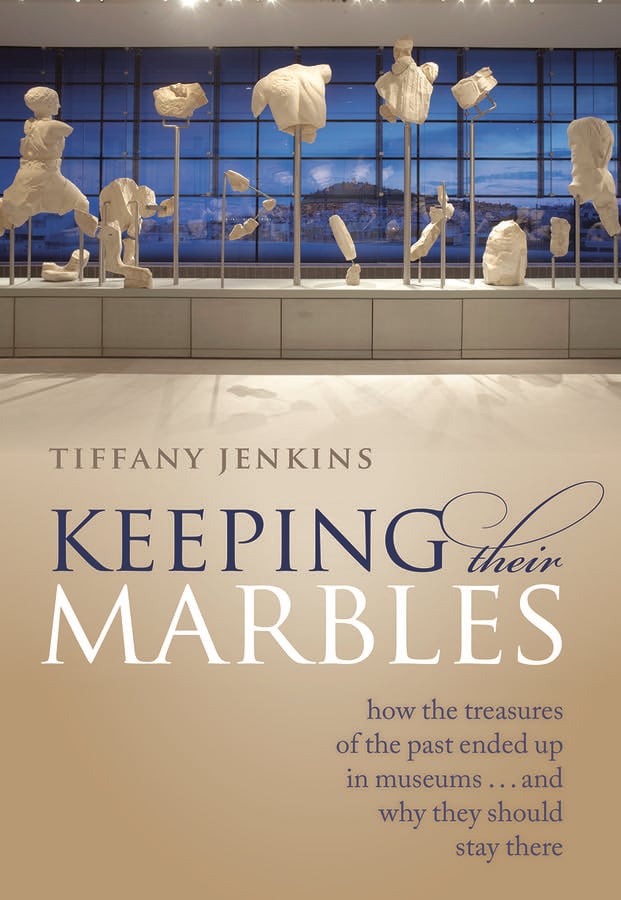

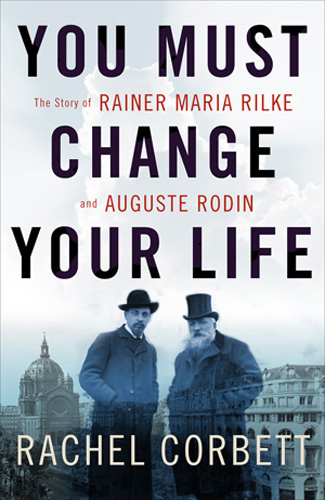

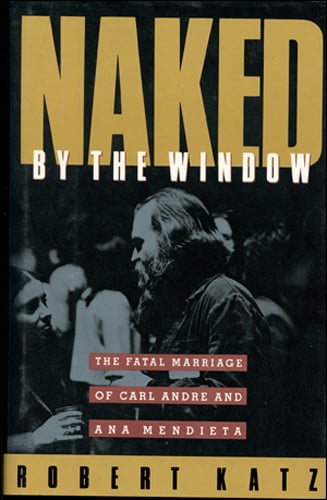

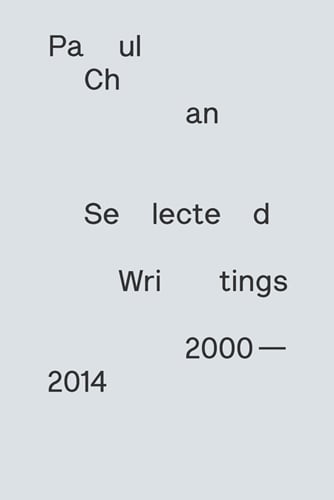

In his forthcoming book, The Art of Rivalry,

Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic Sebastian Smee turns our attention to

four key relationships in the history of Modern art, and he digs deep.

His survey covers the mystifying relationships between Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, who embarked on an obscure and enduring friendship after World War II; Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, who struggled for leadership of a new, 20th century avant-garde; Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas, whose tender relationship collapsed following a skewered painting; and Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, whose lives and work would be inextricably bound beyond the grave.

Central to the book’s theme is also an element of intimacy, which Smee skillfully articulates in anecdotal accounts. Disappointingly, women assume little more than secondary roles in these epic romances. Smee admits in his introduction to focusing instead on the “homosocial” relationships between the artists in question as “uncomplicated by heterosexual passion or chauvinistic condescension.” Gertrude Stein, for instance, plays rebel-rousing sovereign in Matisse and Picasso’s Parisian art world; and artist Ruth Kligman is reduced to “a glamorous younger woman” who embarked on an affair with de Kooning shortly after surviving the car crash that claimed her lover Pollock’s life.

To draw your own conclusions on the most treacherous rivalries in modern art, we offer the following excerpted passages.

On Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon

On Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon

[Artist] Anne Dunn would later claim that Freud “had a kind of hero-worshiping crush on Bacon, though I don’t think it was ever consummated.” What seems undeniable is that the relationship was not only intense but asymmetrical. Bacon was attracted to Freud, who had a way of talking about art that the older man found immensely compelling and tried to emulate.

Insecure about his own lack of facility as a draftsman, Bacon was also eager to learn what he could from his younger friend. Freud was “funnier and more intelligent than Bacon’s average acolytes,” according to William Feaver. But Bacon was indifferent (or so Freud believed) to his work. (When asked if his own interest in Bacon’s work was reciprocated by the older man, Freud replied: “I’d have thought he was completely uninterested. But I don’t know.”) Freud, on the other hand, for one of the only times in his life, was truly in thrall to another person.

On Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso

On Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso

Picasso surely told himself that what he got from African art was very different from what Matisse saw in it. It was more extreme, more potent. The discovery, by his account, was not only more dramatic than Matisse’s curio shop pottering; it was fired by superstition, by magic. Matisse, for his part, would never have dramatized his conception of art in this way. It was not in his interest to do so: People thought he was crazy enough as it was. Better to emphasize ‘planes and proportions’ rather than magic and exorcism.

In any case, an idea of harmony, achieved through sublimation, mattered profoundly to Matisse in a way that it did not to Picasso. Matisse was always shoring himself up against chaos. Picasso meanwhile thrived on dissonance. He welcomed collision and strife.”

On Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas

On Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas

Soon after their fateful 1861 encounter in the Louvre, Manet and Degas were seeing each other several times a week. There were natural affinities between them—not least social and class factors marking them out from most of their bohemian artist peers. But Manet must also have recognized in Degas something brilliant and inimitable. As a student, Degas had worked tirelessly at drawing at drawing. He had a stupendous aptitude for it, one that far outstripped Manet’s.

But he was also disciplined. He had taken to heart the advice of his hero, the formidable neoclassist Jean-August-Dominique Ingres, whose home he had visited as an awestruck student in 1855. Ingres told him: “Draw lines, young man, and still more lines, both from life and from memory, and you will become a good artist.”

On Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock

On Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock

Pollock’s triumph made de Kooning acutely conscious that he, like every other struggling American avant-garde artist, was in Pollock’s shadow. But de Kooning was smart enough to realize that the game had changed. Pollock had achieved what none of them had hitherto looked capable of: He had forced people to look at his work. And he had made sure that once they did, they would not look away without having formed a response that was geared to the aggression in the art itself.

He had done more than just break the ice; he had put his fist through the glass pane separating modern American art from its potentially enormous public. New vistas opened up. De Kooning saw all this. But of course, Pollock’s achievement wasn’t simply about connecting modern art with a public. It was about generating possibilities for the creation of art itself.

The Art of Rivalry: Four Friendships, Betrayals, and Breakthroughs in Modern Art, by Sebastian Smee, hits shelves on Tuesday, August 16.

Follow artnet News on Facebook.

His survey covers the mystifying relationships between Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, who embarked on an obscure and enduring friendship after World War II; Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, who struggled for leadership of a new, 20th century avant-garde; Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas, whose tender relationship collapsed following a skewered painting; and Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, whose lives and work would be inextricably bound beyond the grave.

Central to the book’s theme is also an element of intimacy, which Smee skillfully articulates in anecdotal accounts. Disappointingly, women assume little more than secondary roles in these epic romances. Smee admits in his introduction to focusing instead on the “homosocial” relationships between the artists in question as “uncomplicated by heterosexual passion or chauvinistic condescension.” Gertrude Stein, for instance, plays rebel-rousing sovereign in Matisse and Picasso’s Parisian art world; and artist Ruth Kligman is reduced to “a glamorous younger woman” who embarked on an affair with de Kooning shortly after surviving the car crash that claimed her lover Pollock’s life.

To draw your own conclusions on the most treacherous rivalries in modern art, we offer the following excerpted passages.

Lucien Freud, Reflection (Self-Portrait), 1985. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Francis Bacon, One of Two Studies for a Self-Portrait (1970). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Francis Bacon, One of Two Studies for a Self-Portrait (1970). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

[Artist] Anne Dunn would later claim that Freud “had a kind of hero-worshiping crush on Bacon, though I don’t think it was ever consummated.” What seems undeniable is that the relationship was not only intense but asymmetrical. Bacon was attracted to Freud, who had a way of talking about art that the older man found immensely compelling and tried to emulate.

Insecure about his own lack of facility as a draftsman, Bacon was also eager to learn what he could from his younger friend. Freud was “funnier and more intelligent than Bacon’s average acolytes,” according to William Feaver. But Bacon was indifferent (or so Freud believed) to his work. (When asked if his own interest in Bacon’s work was reciprocated by the older man, Freud replied: “I’d have thought he was completely uninterested. But I don’t know.”) Freud, on the other hand, for one of the only times in his life, was truly in thrall to another person.

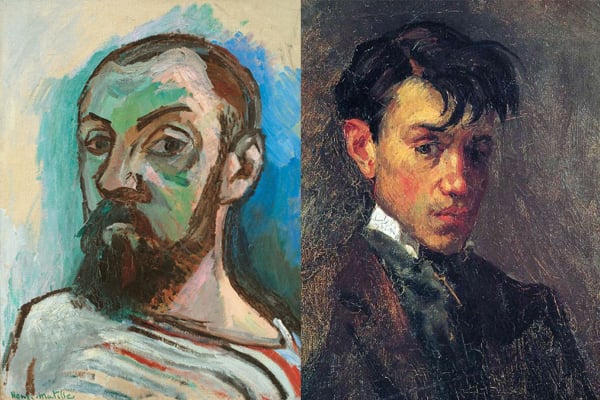

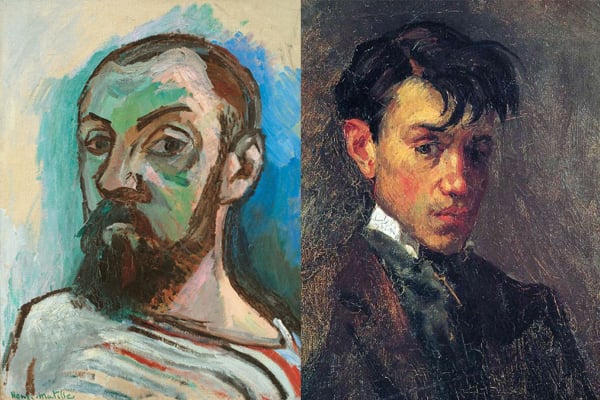

Left: Henri Matisse, Self-Portrait in a Striped T-shirt (1906). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Right: Pablo Picasso, Portrait with Uncombed Hair (1896). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Picasso surely told himself that what he got from African art was very different from what Matisse saw in it. It was more extreme, more potent. The discovery, by his account, was not only more dramatic than Matisse’s curio shop pottering; it was fired by superstition, by magic. Matisse, for his part, would never have dramatized his conception of art in this way. It was not in his interest to do so: People thought he was crazy enough as it was. Better to emphasize ‘planes and proportions’ rather than magic and exorcism.

In any case, an idea of harmony, achieved through sublimation, mattered profoundly to Matisse in a way that it did not to Picasso. Matisse was always shoring himself up against chaos. Picasso meanwhile thrived on dissonance. He welcomed collision and strife.”

Left: Edouard Manet, Self Portrait with a Palette (1879). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Right: Edgar Degas, Self-Portrait (1855). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Soon after their fateful 1861 encounter in the Louvre, Manet and Degas were seeing each other several times a week. There were natural affinities between them—not least social and class factors marking them out from most of their bohemian artist peers. But Manet must also have recognized in Degas something brilliant and inimitable. As a student, Degas had worked tirelessly at drawing at drawing. He had a stupendous aptitude for it, one that far outstripped Manet’s.

But he was also disciplined. He had taken to heart the advice of his hero, the formidable neoclassist Jean-August-Dominique Ingres, whose home he had visited as an awestruck student in 1855. Ingres told him: “Draw lines, young man, and still more lines, both from life and from memory, and you will become a good artist.”

Left: Willem de Kooning, Woman III (1953). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Right: Jackson Pollock, Number 3 (1948). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Pollock’s triumph made de Kooning acutely conscious that he, like every other struggling American avant-garde artist, was in Pollock’s shadow. But de Kooning was smart enough to realize that the game had changed. Pollock had achieved what none of them had hitherto looked capable of: He had forced people to look at his work. And he had made sure that once they did, they would not look away without having formed a response that was geared to the aggression in the art itself.

He had done more than just break the ice; he had put his fist through the glass pane separating modern American art from its potentially enormous public. New vistas opened up. De Kooning saw all this. But of course, Pollock’s achievement wasn’t simply about connecting modern art with a public. It was about generating possibilities for the creation of art itself.

The Art of Rivalry: Four Friendships, Betrayals, and Breakthroughs in Modern Art, by Sebastian Smee, hits shelves on Tuesday, August 16.

Follow artnet News on Facebook.

Share

Article topics