Staff Picks: Horses, Heaney, and Hypebeasts

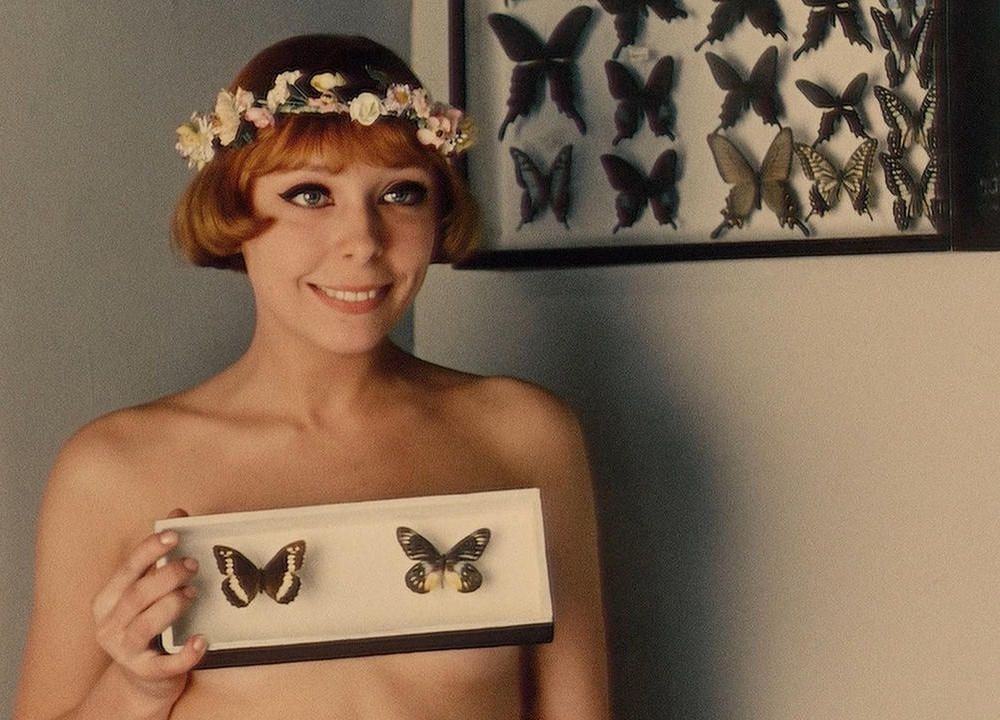

You’ve probably seen Daisies, Věra Chytilová’s dizzying 1966 masterpiece, especially if you were a young woman in the early aughts browsing LiveJournal or Tumblr, where screenshots of its two heroines dancing, throwing food, and declaring themselves “spoiled” abounded. But it’s difficult to find the rest of Chytilová’s films. Over the years, I’ve seen only two: the aforementioned Daisies and 1963’s Something Different, available via the Criterion Collection. That’s why I’m excited to spend the next few days essentially living inside the Brooklyn Academy of Music for their series “The Anarchic Cinema of Věra Chytilová.” What does a teen horror movie–meets–metaphor for authoritarian repression look like under a director like Chytilová? Or a comedic critique of the aging male libido? I guess I’m going to find out this weekend—and maybe you will, too. —Rhian Sasseen

There’s a woefully sparse amount of Seamus Heaney in the Paris Review archive (two poems and an Art of Poetry interview), but a selection of a hundred Heaney poems, newly compiled by his daughter five years after his death, will be released this summer. In her tender introduction, Catherine Heaney writes that she hopes “a newcomer will enjoy reading these poems for the first time, and that the long-time devotee might rediscover a forgotten favourite or simply listen again to the poetic voice as it changes and matures over the course of the years.” Reading through this relatively slim selection of Heaney’s understated verse, I was both new initiate and old friend; as I lingered, I felt a gratitude for Heaney and a pang of loneliness that he is gone. The last line of his poem “Blackberry-Picking” sings this conflicted sense of mourning beautifully: “Each year I hoped they’d keep, knew they would not.” —Lauren Kane

Jenifer Sang Eun Park’s Autobiography of Horse—out this month from Gaudy Boy, a new indie press that publishes authors of Asian heritage—documents her “critical obsession” with horses. The obsession is “critical” in that it is turned toward and engaged with. There are risks associated with telling people you love anything: “This is when people give you things imprinted with the horse—a book, a mug, a poster, a sticker, a shot glass, a stuffed horse, etc.,” she writes. “Each gift is another device for torture.” It’s not that the gifts are ill-intended. In fact, this kind of gesture reminds me of all the small ways we try to reach each other on a daily basis: repeatedly, frenetically. Gestures nearly always result in a mix of recognitions and misses. Would we really want a gesture to make us feel entirely seen—that is, transparent? After reading Jenifer Sang Eun Park, I am more willing to accept life’s inevitable excess, though it’s terrifying: “I’m afraid of looking into the horse’s eyes and finding in that single gaze the meaning of both hatred and love.” Autobiography of Horse is a high-wire act of accepting a multiplicity of voices and forms. It slips into different personas, into images, back to text. The book asks its reader: Will you hold all of these things at once? Sometimes the horse knows itself to be good enough, sometimes less so. Sometimes the horse is hiding, but always, by putting itself on the page, the horse is not alone. —Spencer Quong

There are some days I feel as old as subway tiles, and this week was a string of them. Postponing an email I felt too ancient to type, I read a profile of the singer-songwriter Tayla Parx. I like a woman who knows her strengths, and I love a writer behind the scenes. Parx is both, and she’s an all-star. She’s written No. 1 hits in nearly every genre, perhaps most notably for Ariana Grande, but her own music is what provided the Aphrodite dip I was looking for. Parx’s videos for “Me v. Us” and “I Want You” overflow with juicy hues, and her completely magnetic presence gave me the spring-dress feeling I never feel. It’s pop with pop. And instead of griping about autotune or kids these days, I just adjusted my headphones and bumped up the volume. —Julia Berick

Along with the rest of the internet, I’ve spent the past two weeks wandering in an angsty trance spurred by the pop singer Billie Eilish’s new album, When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? If you’ve heard about it, you likely fall into one of two camps. The first holds a highbrow suspicion of the seventeen-year-old homeschooled hypebeast. But I’m not onboard with the popular inclination to deny teenage girls credit for their significant cultural influence, so I fall into the second group: those who are awestruck and raving on Twitter. When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? is not a perfect album (I skip “xanny” and “wish you were gay”), but songs like “ilomilo” are so good I’ve been hopping off the subway early and walking the rest of the way home, seeking out moments of solitude so I can rest my mind in Eilish’s ambiguous emotional void. It’s easy to call her some mix of Lorde, Banks, and maybe FKA Twigs, but those parallels feel insufficient. Eilish’s best quality is the contradiction she represents: fragile but invincible, scared yet defiant. In “you should see me in a crown” and “bury a friend,” a darker, bass-dropping bravado is accentuated by the sound of a knife being sharpened and an unsettling shriek. Eilish is prepared to duel with an eerie growl, but in “when the party’s over,” she offers a reluctant vulnerability, lilting “I could lie, say I like it like that.” A tension remains between the image she creates—lounging in Louis Vuitton cargo shorts or chomping down on a spider—and the soft hum of her voice. Perhaps this is what’s most striking and appealing about Eilish: despite the swagger, her music contains an underlying anxiety and the desire to push beyond it. It’s a feeling I identify as distinctly teenage girl, which is to say human. —Nikki Shaner-Bradford

BILLIE EILISH. PHOTO: JUSTIN HIGUCHI FROM LOS ANGELES, CA, USA (CC BY 2.0 (HTTPS://CREATIVECOMMONS.ORG/LICENSES/BY/2.0)).