Visual Culture

These Little-Known Photographers Explored the Female Gaze in 1960s Mali

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1954-1960. © Seydou Keïta-SKPEAC. Courtesy of CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection.

In late February, during what has become Marrakech’s busiest art week, images by the late Malian studio photographer

were pasted up on walls around the city’s medina area. The public installation was organized by the Musée d’Art Contemporain Africain Al Maaden (MACAAL) as an extension of the museum’s newly opened exhibition on the politics of place and space. The now-iconic photographer is known for the striking black-and-white portraits he shot at his outdoor studio before and immediately after Mali became an independent nation in June 1960. His portraits became defining images of a new society on its own terms.

Keïta has been hugely influential as one of the first Black African photographers to document his city, and he has risen to international prominence since participating in the Guggenheim’s group exhibition on African photographers in 1996. However, as the concurrent exhibition across town proved, Keïta was not the only photographer defining the image of African independence. There are many stories from that golden age of studio photography, between 1960 and 1980, that are yet to be told. And one of those vital narratives centers on the female gaze.

Seydou Keïta, Untitled, 1952-1955. © Seydou Keïta-SKPEAC. Courtesy of CAAC – The Pigozzi Collection.

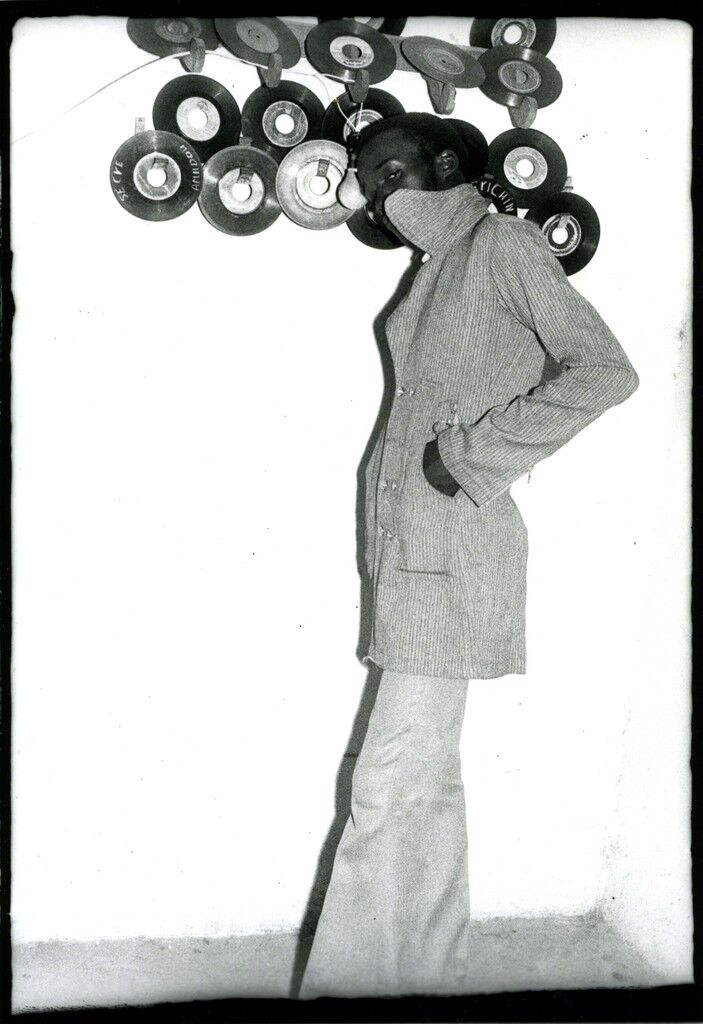

Until now, many of the most famous images to have come out of Mali’s studio photography archives have featured male subjects or mixed couples. Take, for example,

’s suited figures, such as the man who poses in Je Suis Fou Des Disques (1973), or another in Un Ye-ye en position (1963), wearing shades and flared trousers; or Keïta’s shot of a young cosmopolitan figure, circa 1955, posing with a telephone. But the recent exhibition “Her Eyes, They Never Lie,” featuring works by the lesser-known Mali-based photographers

and

, showed that women were active contributors at the studios, claiming their gaze and shaping their own image. The fact that the two photographers were men is a deliberate way to shake up the common definition of the “female gaze.” “The African studio photographers’ gaze was very different to the Western male gaze,” explained Lisa Anderson, the show’s curator.

“Her Eyes, They Never Lie”—which was on view at Marrakech’s Jnane Tamsna hotel in the Palmeraie from February 19th to 23rd—took its title from Tony Montana’s famous line in Scarface (1983), referring to the way women’s looks are frequently misread. The exhibition features never-before-seen prints created between 1956 and 1973 by Kouyaté, who passed away a week before the opening on February 14, 2020, and by Sakaly, who died in 1988 and whose studio—once a local landmark—closed in 2002. Sakaly had mostly been forgotten outside of Mali.

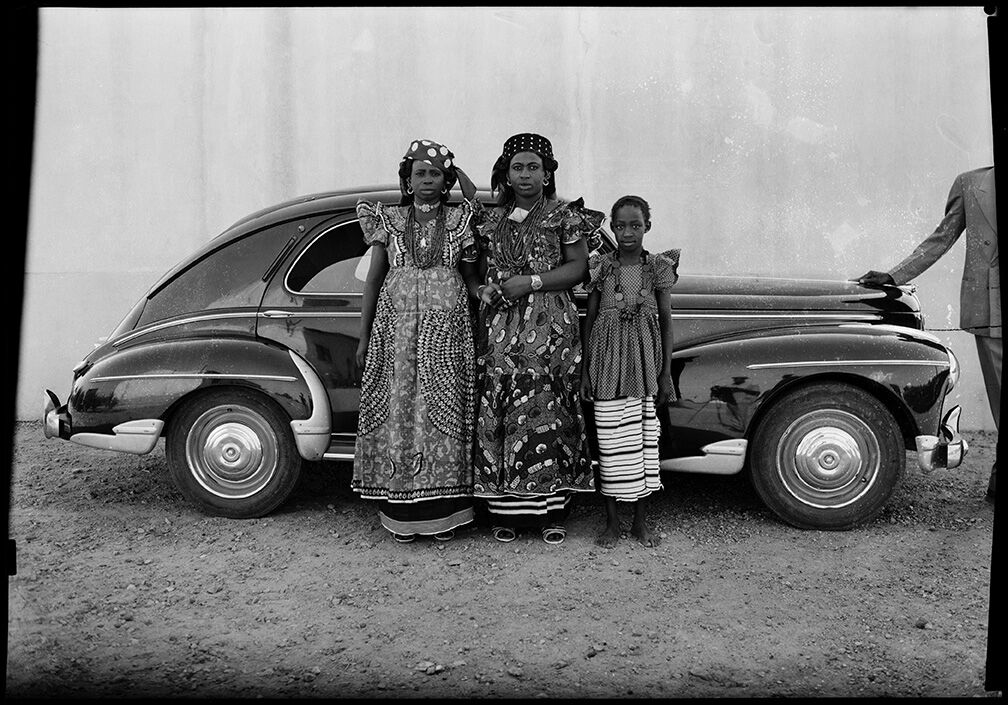

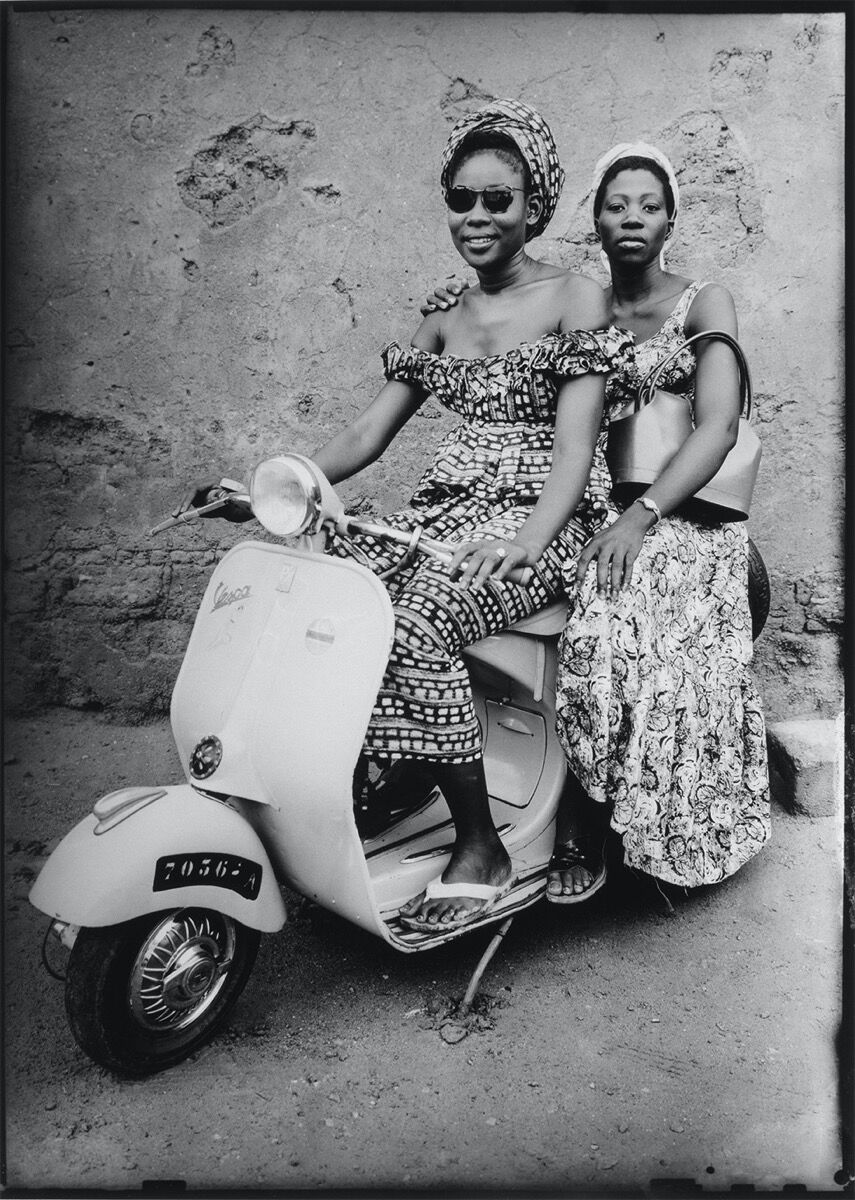

Abdourahmane Sakaly, Jeunes copines, May 1962, 1962. Courtesy of the artist and Black Shade Projects.

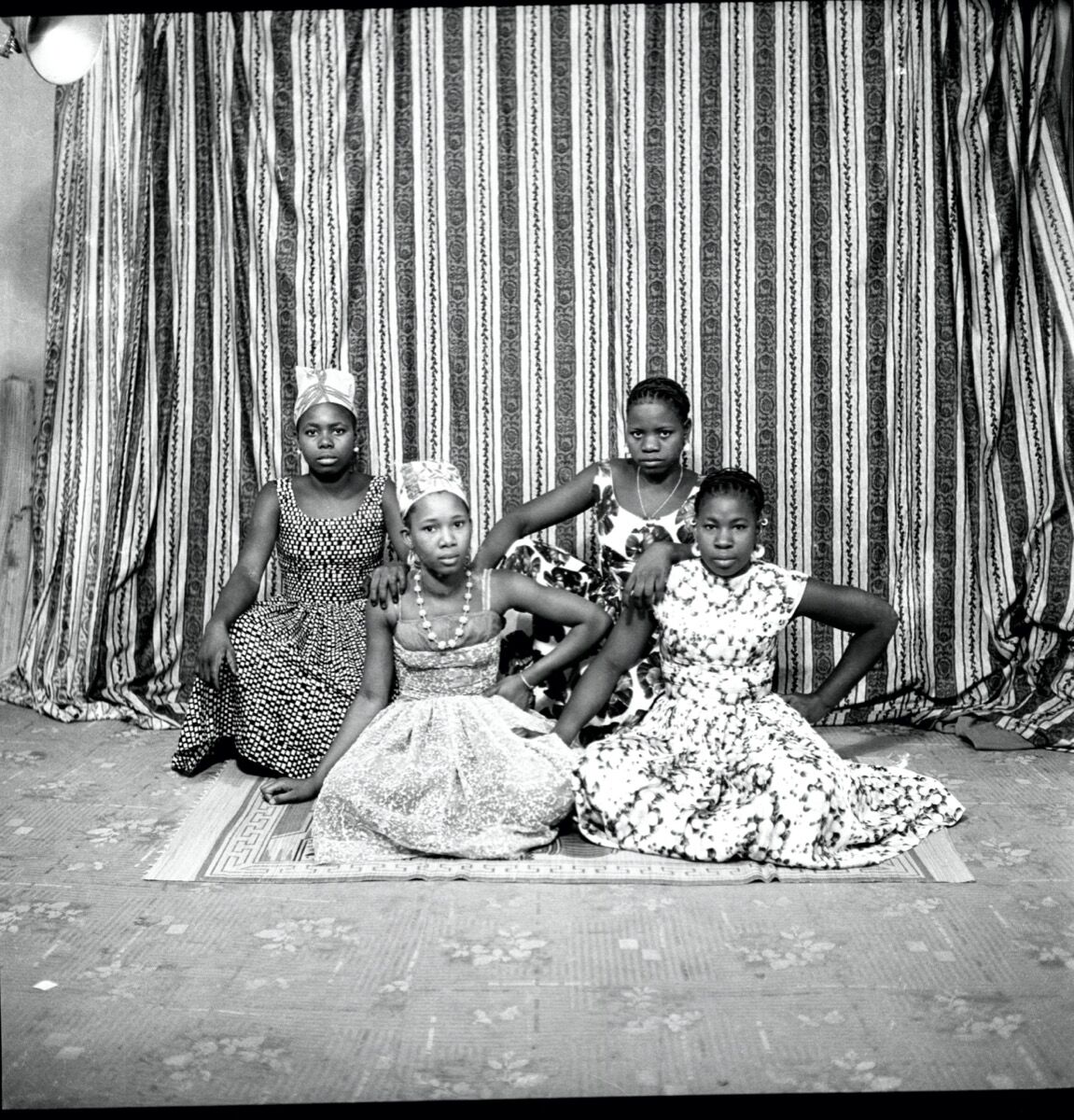

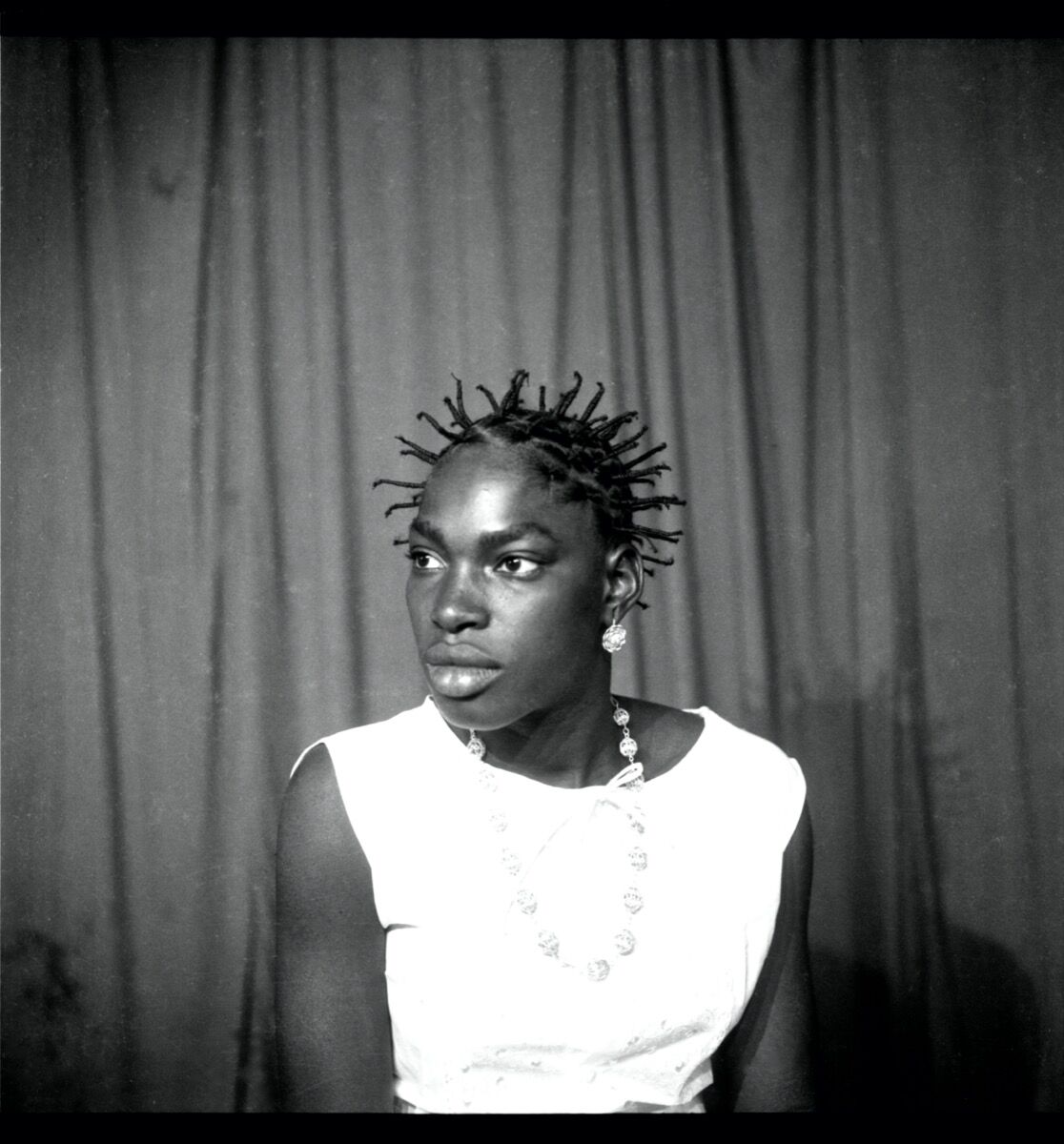

Focusing only on female subjects, the images in the exhibition are striking portraits of self-determination that show that there was no one female archetype at the time. In one image by Sakaly, a group of four young sitters on the cusp of womanhood pose solemnly and confidently, each dressed impeccably in frocks and jewelry. In a contrasting 1967 portrait by Kouyaté, four older women crouch in elegant, voluminous dresses and headwraps; their expressions are less unified and more self-conscious. One of Sakaly’s standout works is an enigmatic portrait of a young woman simply noted as having a “beautiful hairstyle,” shot in 1963. Dressed in a simple white sleeveless top, she gazes out of the frame rather than back at the photographer and his camera.

“I love reading the pose, I love reading the eyes,” Anderson said of Kouyaté’s and Sakaly’s photographs. “As a Black woman, I feel I am often misread as aggressive or upset or defensive. I want to complicate and enrich the ways these gazes are experienced and interpreted and understood, because there’s important knowledge in there for everyone.”

Anderson worked with Black Shade Projects, a platform for African photography based between London and Marrakech founded by art advisor Myriem Baadi. One of Sakaly’s younger sons, Youssouf, who now looks after the artist’s archives, explained that his father, a contemporary of Keïta and Sidibé, was an immigrant from Senegal who arrived in Bamako in 1946 and set up his own studio in 1956. According to his son, Sakaly, who was born in Senegal and was of Moroccan heritage, was one of the first photographers in Bamako—if not the first—to develop his film at his studio rather than send it abroad.

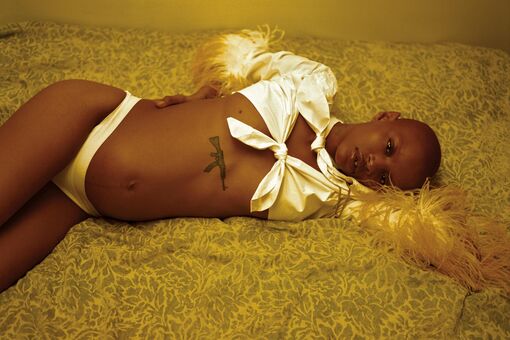

Adama Kouyaté, Jeune fille Amoureuse, November 1969, 1969. Courtesy of the artist and Black Shade Projects.

Abdourahmane Sakaly, Portrait de femme à la belle coiffure , August 1963, 1963. Courtesy of the artist and Black Shade Projects.

The women who visited Sakaly’s studio in Bamako’s market or Kouyaté’s studio in Ségou in the 1960s and ’70s would dress in their best clothes and accessories. The effect is a remarkable sense of agency in these images; the photographs reflect how the sitters wanted to be seen—as the best versions of themselves. “You can tell from the images that these women are not objectified, this was collaborative, and they’re celebrated,” Anderson said.

“These photographers were custodians of culture,” she continued. “They were uncles who revered and cherished their subjects; they were there to capture your memories and your family.” They also had to create images that made their clients happy in order to stay in business, she added. “They couldn’t go around upsetting people! It was a very different dynamic to be a commercial photographer,” Anderson said.

“Her Eyes, They Never Lie” doesn’t only focus on the photographer’s gaze on the female subject, but also on the gaze of the individuals in the photographs, as well as Anderson’s curatorial gaze on them. The show also included a performance and multimedia work by contemporary artist

, inspired by a personal photograph of her mother as she arrived in the U.K. from Ghana.

Adama Kouyaté, On est ensemble, January 1967, 1967. Courtesy of the artist and Black Shade Projects.

“I want to explode some myths around the African female gaze,” Anderson explained, noting that her curatorial research has been foregrounded in the 2019 exhibitions at Toronto’s Ryerson Image Centre and at Brooklyn’s United Photo Industries Gallery. “Her Eyes, They Never Lie” is the first time the African female gaze in photography has been explored on the African continent. The show also coincided with the first retreat celebrating African contemporary creativity—an exclusive, invite-only event organized by AFRƎEculture, also taking place at the hotel.

Although the women in these portraits are anonymous and unnamed, they offer rich insights into the lives of women during the first years after independence: mothers and daughters, groups of friends, aunties, teenagers, young women. Their expressions, poses, and gestures—finger to chin, a coquettish glance, a wistful stare—together with the details of their clothing, hair, and accessories all show how creativity and originality were fundamental in the performance of one’s self. They also reframe the history of the female gaze, locating it in Africa and more than a decade before the popular ideas of the artists working in the West in the 1970s.

“It was something new and exciting in that first decade when you were able to control your image and own it to some extent,” Anderson said, drawing an analogy with the introduction of Instagram selfies, which have been equally important for the development of the female gaze in photography on a global scale. “Historically, culturally, and socially, it was a way of celebrating the power to control the image.”

Charlotte Jansen