The Most Iconic Artists of the Italian Renaissance, from Masaccio to Titian

- Art History 101

Unfolding from around the year 1300 to the middle of the 16th century, the Italian Renaissance

was one of the most important and prolific periods in the history of

art. The Renaissance (the French word for “rebirth”) refers to the

rediscovery of ideals from classical antiquity. A system of values that

came to be known as humanism, these ideals turned away from the dogma of

medieval scholasticism in order to advance education in rhetoric,

history, moral philosophy, and other liberal arts. While this rebirth

occurred in many creative realms—the poetry of Dante Alighieri, the

architecture of Filippo Brunelleschi, the scientific experiments of

Galileo Galilei—certain works of visual art stand as the most iconic

representations of the Renaissance and its principles. Indeed, this is

the period when the most famous images shifted from being icons—representations of holy figures like Christ or the Virgin Mary imbued with special devotional powers—to being iconic in a secular sense.

- Church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence

Masaccio’s early Renaissance Trinity with the Virgin, Saint John the Evangelist, and Donors (ca.

1425-27/28) in the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, in Florence,

demonstrates this renewed interest in human, rather than only divine,

religious space. Through the scientific application of one-point, linear

perspective, the fresco is considered to have depicted

three-dimensional space on a flat surface for the first time since

antiquity. By giving the illusion of depth in the representation of the

vault’s coffers, and by portraying the figure of Mary gesturing to the

viewer, the Trinity creates a conduit between the space of the viewer and the realm of the divine.

- Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

- Orsanmichele, Florence

As the first free-standing nude since the Classical period, Donatello’s David (c.1440-43)

demonstrates a strong impulse toward antiquity. Not only did Donatello

employ the ancient Greek and Roman technique of lost-wax casting to

create a form of hollow bronze, but his sculpture also celebrated the

human body rather than just the spirit, echoing the engagement with

beauty and pleasure in classical cultures. This can be seen in David’s

sensual form, a lithe body cast in a curving pose. The asymmetrical

balance of his stance, with one hip forward and his weight shifted to

one leg, demonstrates a classic Renaissance technique called contrapposto.

Representing the Biblical story of “David and Goliath,” Donatello’s sculpture was also a metaphor for the might of the small Florentine Republic in the 15th century. While often at war with neighboring powers like Milan, Florence maintained a cultural importance that exceeded its small size. The famous Medici family was the most powerful in Florence and the city’s most ardent patron of art.

Representing the Biblical story of “David and Goliath,” Donatello’s sculpture was also a metaphor for the might of the small Florentine Republic in the 15th century. While often at war with neighboring powers like Milan, Florence maintained a cultural importance that exceeded its small size. The famous Medici family was the most powerful in Florence and the city’s most ardent patron of art.

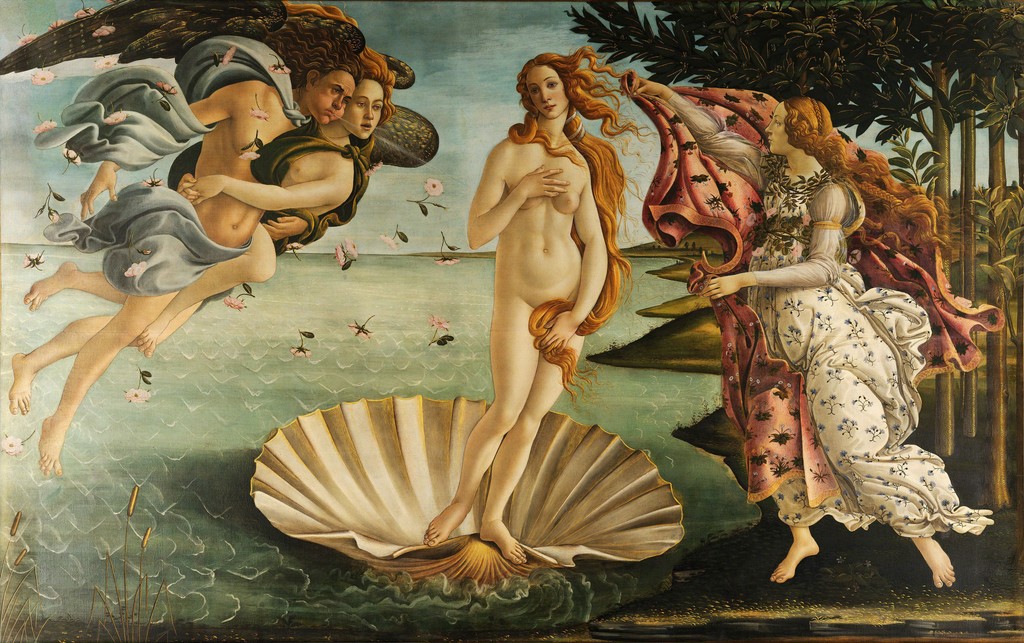

- Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Painted in the 1480s for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (ca. 1486) took

its theme from Ovid’s “Metamorphoses.” One of the most iconic images in

all of Western art, Botticelli’s painting reinterprets an ancient Greek

statue of Venus in a Neoplatonic mode, depicting a nude female body as

an allegory of both physical and divine beauty. Incorporating traces of

real gold in Venus’s hair, the work exemplifies the Golden Age of

Quattrocento painting.

The onset of the 15th century leads to the High Renaissance and the most famous work of art in the world today: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503–06). Coming of age in Florence and Milan, Leonardo had already completed other illustrious works—the Vitruvian Man (ca. 1409) and the The Last Supper (1495–98)

are prime examples—when the merchant Francesco del Giocondo

commissioned him to paint a portrait of his wife, Lisa Gherardini, in

1503. (The work is sometimes called “La Giocondo,” hence the painting’s

French nickname “La Joconde”). In an age when portraiture was

increasingly popular, Leonardo’s unusual approach—giving a half-length,

closely focused view of the sitter—earned immediate praise. Relating the

sitter to forms in the landscape behind her and layering paint in an

innovative way that created the soft, smoky effect called sfumato, Leonardo also endowed Mona Lisa with an enigmatic smile that has become her most alluring feature.

While

Leonardo argued for the superiority of painting in both his artwork and

writing, the younger virtuoso Michelangelo (born Michelangelo

Buonarroti) claimed that sculpture was the supreme art. Their rivalry

was part of the ongoing Renaissance debate of paragone, which

asked what the ultimate form of art was: painting or sculpture. Like

Leonardo, Michelangelo was a polymath, an exceptional talent in many

fields. Yet although he redesigned the architecture of St. Peter’s

Basilica and arduously painted the revered frescoes in the Sistine

Chapel (including the iconic Creation of Adam, 1508–12), Michelangelo considered himself first and foremost a sculptor.

No work encapsulates his so-called divine gifts or ambition so much as the colossal David (1501–04). Based on the same Old Testament story of “David and Goliath” that inspired Donatello years earlier, Michelangelo’s 14-foot-tall sculpture offers a different interpretation. Rather than standing on the head of the slain giant in the aftermath of battle, this muscled, heroic nude in contrapposto pose stares intensely the moment before the confrontation. Carving such a large figure from a block of marble was a precocious technical achievement for an artist in his 20s, but Michelangelo’s clear grasp of human anatomy astounded his contemporaries.

No work encapsulates his so-called divine gifts or ambition so much as the colossal David (1501–04). Based on the same Old Testament story of “David and Goliath” that inspired Donatello years earlier, Michelangelo’s 14-foot-tall sculpture offers a different interpretation. Rather than standing on the head of the slain giant in the aftermath of battle, this muscled, heroic nude in contrapposto pose stares intensely the moment before the confrontation. Carving such a large figure from a block of marble was a precocious technical achievement for an artist in his 20s, but Michelangelo’s clear grasp of human anatomy astounded his contemporaries.

- Stanza della Segnatura, Vatican

The Italian Renaissance reached its zenith in the first decades of the 16th century, and Raphael Sanzio’s School of Athens (1510–12)

is a culmination of the era’s classical style and spirit. Part of a

series of frescoes in the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace, The School of Athens

offers a synthesis of technical refinement, linear perspective through

perfected architecture, and the personification of philosophical ideals.

The figures represent the most renowned minds of antiquity (Plato and

Aristotle are framed at center by concentric arches) as well as a number

of the artist’s contemporaries, including Leonardo, Michelangelo, and

Raphael himself.

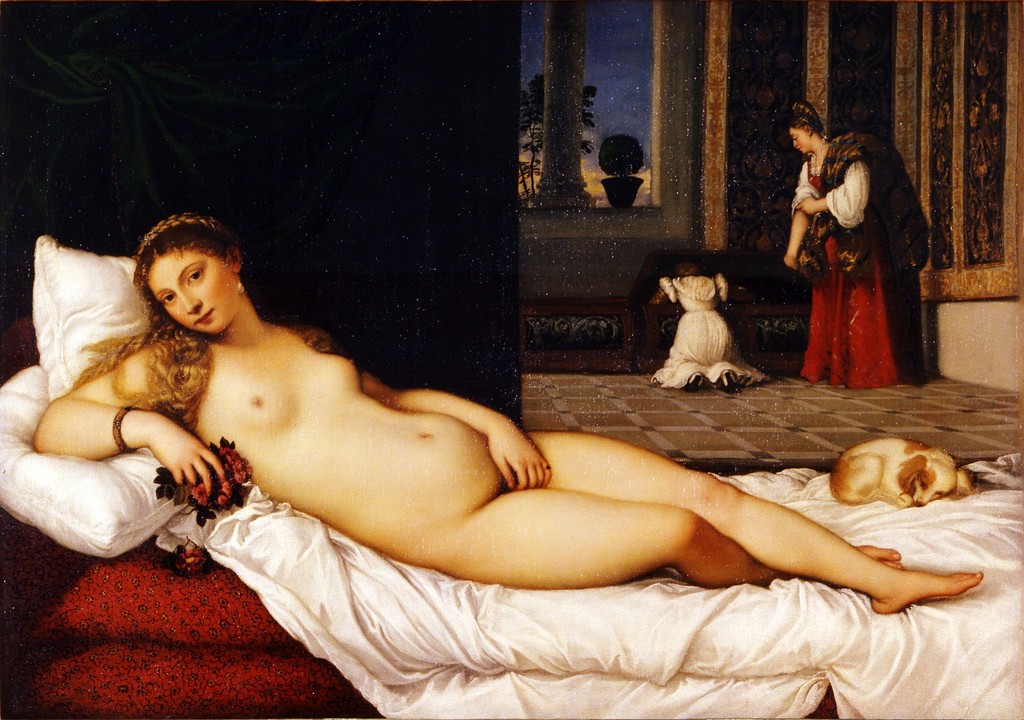

- Uffizi Gallery, Florence

While

the Renaissance installed these Neoplatonic ideals in Western culture,

it also generated changes in the social regard and purposes of art. If

Florentine artists were known for the clarity of their design, Venetian

artists were known for their mastery of color. Titian was the greatest

painter of that school, bringing a rich palette to his portraits,

altarpieces, and mythological subjects like Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–23). His Venus of Urbino (1538),

one of his best-known of his works, approached the nude with

specificity and sensuality. This is not the sleeping goddess painted a

few years earlier by Giorgione, but a real woman in flesh and blood,

reclining on the sheets in front of the viewer. A testament to its

iconic status, Titian’s Venus would later be quoted by artists like Édouard Manet.

Many of these explorations in subject and color are considered examples of Mannerism,

an evolution of style around the end of High Renaissance classicism.

Mannerist tropes are already evident in mature works by Leonardo,

Raphael, and Michelangelo, but Agnolo Bronzino’s An Allegory with Venus and Cupid (1544–45) displays the eroticism and obscure allegories that define the genre.