THE TAKE

Everything You Know About Modernism Is Wrong: 7 Canon-Busting Lessons from “Modern Art In America”

Everything you know is wrong. And the truth is perhaps more interesting.

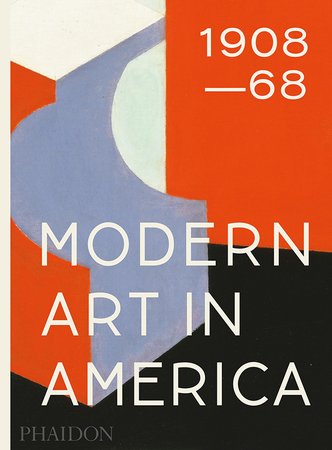

The art historian William C. Agee released Modern Art in America, 1908-1968 via Phaidon Press this spring, and, to a not inconsiderable degree, it upends some long-held tenets, clichés, and canons of the art world.

To oversimplify Agee’s compelling contention, much of early 20th-century American art history was jettisoned either because it either didn’t make a good story for the press, a cohesive argument for historians, or a particularly flattering narrative for those artists who came afterward. There were artists whose work had to be written out of the story of a particular period (the late work of Stuart Davis, for instance) or minimized in importance in order to streamline the pedigree of American art (Edward Hopper). Add to this American culture’s long-held “inferiority complex,” he says, and the Eurocentric bias of Museum of Modern Art founder Alfred Barr and powerful art critic Clement Greenberg, and you have a flawed retelling of what, and who, actually mattered.

The world is full, of course, of academics basing their dissertations on the argument that Regional Brushstroke and Swatch McGee were the real unheralded superstars of modern art. But Agee is no green art history undergrad. A curator at MoMA and the Whitney, and a former director at the MFA Houston and professor at Hunter College for the last two decades, he’s presented some of the more notable museum shows of the last 40-odd years. Perhaps most importantly, in terms of impact, he’s a principal advisor of Walmart heiress Alice Walton, whose Bentonville, Arkansas, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art is perhaps the most ambitious new museum project of the century to date.

So when he says that many artists, and even entire decades of American art, got short shrift—the 1920s in particular, he argues, is wrongly considered “a dark age”—perhaps it’s worth listening.

Georgia O'Keeffe's Grey Line with Black, Blue and Yellow, 1923

Agee writes: "As art in the United States gained international attention after 1945, earlier American art was cast off by critics and curators as a kind of demented uncle, in favor of establishing a more elevated pedigree, a celebrated cast of exalted Europeans such as Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró. No doubt these Europeans were crucial, but more was owed to American art prior to 1945 than anybody understood, or cared to admit." (emphasis ours)

Here, some of his more radical arguments:

1) It’s not, as it has often been suggested, that American artists were slow to “get” Impressionism (or, less so, Cubism), but rather that they had little use for it.

What American painters embraced, instead, decades earlier and more enthusiastically than many of their European counterparts, was the ascendance and importance of color.

Agee writes: "American artists mostly missed the point of the [Impressionist] movement, and did little with it, except to brighten their palette while retaining tight drawing and brushwork. It may be that Americans had less need for it: they already had their own light and openness, right there, in the grandeur of the continent itself."

If anything, they were ahead of the game.

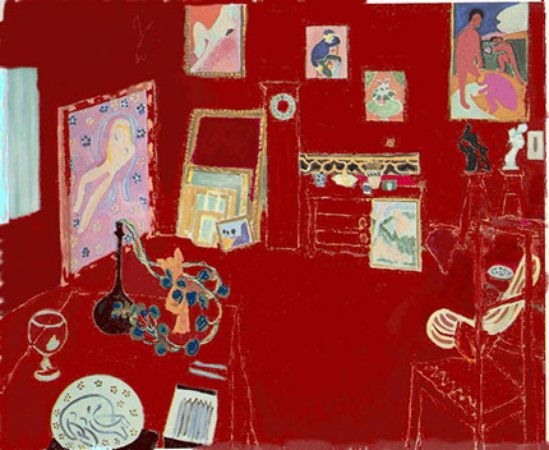

Henri Matisse, The Red Studio, 1911

Henri Matisse, The Red Studio, 1911

2) The importance of Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase II at the 1913 Armory Show has been overblown.

The Cubist work actually wasn’t the superstar of the 1913 Armory show, Agee contends—Duchamp's vertical image was just the easiest to reproduce (and to parody in cartoons) in publications.

Instead, the color, energy, and explosiveness of Vincent van Gogh’s olive trees and Starry Night had a massive impact, he argues; Stuart Davis, the youngest artist to exhibit, made an impression; Paul Cézanne, a massive influence on the artists who followed him, was also on display. And, strikingly, the technique of “sequential movement” that Duchamp used in his much-ballyhooed Nude was also employed, though not noticed or credited, in another work in the exhibition by a female American painter, Kathleen Cunningham.

While Agee doesn’t question Duchamp’s brilliance and massive historical importance, when it comes to the 1913 show, Henri Matisse’s The Red Studio arguably had greater, longer-lasting impact, influencing Andy Warhol, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Davis, among others. It was “the first painting to depend entirely on color.”

3. Movements, Schmovements

Forget the charts of Art History 101. Agee doesn’t worship at the temple of hard-and-fast lines between the Ashcan School, Ab-Ex, Color Field, etc., arguing that many artists' careers bridge those eras and that an art history broken down by movements hauls in names who wouldn’t make it in otherwise.

He writes: "The reputations of too many secondary and tertiary artists have clung on for too long, clouding the waters. American—and all modern—art has had a difficult time determining just who its best artists are, preferring instead to affix artists to the numerous movements and the most recent spectacles. An important principle in this book is therefore to forget movements and concentrate on the artists, to look closely and carefully at their art."

Artists in the early part of the 20th century that Agee elevates and illustrates include John Sloan, Marsden Hartley, s cadre of influential Mexican muralists, and, as a teacher whose influence would reverberate for decades, Robert Henri.

John Sloan's modernist work The Wake of the Ferry II, 1907

John Sloan's modernist work The Wake of the Ferry II, 1907

4) To make their innovations more important, America's postwar artists had to argue, falsely, that nothing else had come before.

In his chapter on the 1940s, Agee argues that self-aggrandizing young artists sought to wipe out earlier history. And, indeed, he notes elsewhere that in 1970, Barnett Newman wrote that, “about 25 years ago, painting was dead… I had to start from scratch as if painting didn’t exist.”

But long before modern American art was supposedly invented in 1945, O'Keeffe was working in New Mexico, Arthur Dove in Long Island, and John Marin in Maine, he points out, but without a critical mass to applaud them. These artists “presaged any of the developments that came after them.”

5) We’re teaching modern art history wrong.

Agee writes: "We teach modern art as a series of radical innovations introduced by ever-younger artists, but we forget that the older artists keep on working, adding immeasurably to the passing decades, often doing their best art in their old age. Think of Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Cézanne, Monet, Matisse, and others; to this, in America, add Marin, Dove, Stuart Davis, Josef Albers, and Hans Hofmann, all of whose late works are nothing less than glorious."

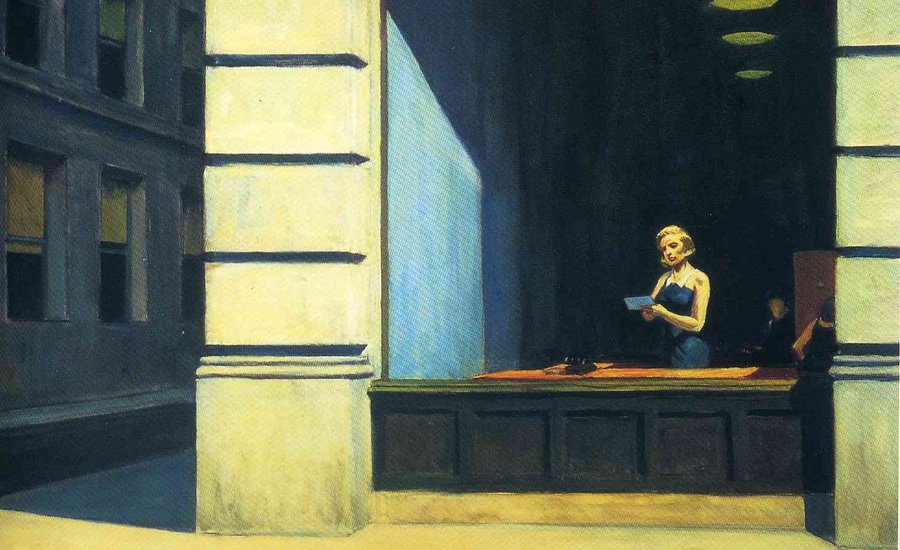

New York Office by Edward Hopper, 1962

New York Office by Edward Hopper, 1962

6) "Hopper was a far greater artist than we have given him credit for."

Hopper has been misunderstood “as a simple homespun realist… We have mostly seen him as a purveyor of alienation, one of the most overused and misconceived clichés in American art history.” Agee argues.

Some others who merit the scholar's effusive phrase: Dan Flavin, whose misnamed “Minimalism” was actually marked by the brilliant use of high color, and Frank Stella, “our greatest living artist.” Several women artists are lauded in the highest terms, including Eva Hesse, Helen Frankenthaler, and Janet Sobol, whose poured paintings, pre-dating Pollock’s and viewed by him at the Peggy Guggenheim gallery, were discounted during her lifetime because “she was an amateur and a woman.”

Janet Sobel's Milky Way, 1945, in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Janet Sobel's Milky Way, 1945, in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

7) The watershed year of 1945 is a canard.

While many art texts have been dubbed “'Art Since 1945,' or some variation,” it’s a false distinction. While working in the U.S. a few years earlier, Piet Mondrian created arguably the first American color-field painting; Guggenheim opened her gallery Art of This Century in 1942; The New Yorker coined Abstract-Expressionism in 1946.

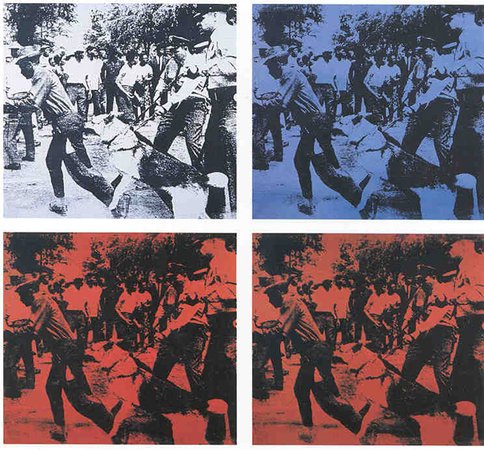

If anything, the 1950s mattered more, Agee argues, as a golden era of broader American culture, and “1957 brought a shift of borders and clearer forms that was to define the look of the 1960s.” And by 1964, with Race Riot, "Andy Warhol establishes himself as the most relentless of social realist and social protest artists the country has produced."

Andy Warhol's Race Riot, 1964

Andy Warhol's Race Riot, 1964

Agee concludes one section in his book with the note: “This book is a history—one of the many possible histories that could be written.” But it may well influence the ones that follow.