|\| ART BLOG HUMOR BLOG PHOTO BLOG CULTURE BLOG |:| FOR THE RENAISSANCE MAN & THE POLYMATH WOMAN |/|

Tuesday, July 24, 2018

Art Gets Damaged All the Time. Here’s How It Gets Back to the Market

Sculpture damaged by an earthquake in Italy, 2016. Photo by Marco Zeppetella/AFP/Getty Images.

When a fire broke out in a second-floor storage space of Paula Cooper Gallery on July 10th, a number of Chelsea galleries were thrown into a mad scramble to save their valuable artworks. The cause of the fire, believed to have been electrical, is still under investigation, as is the extent of the fire and smoke damage to both the building and any works inside it.

A high-profile disaster, such as a fire in New York’s Chelsea gallery district, raises the question of what exactly happens when an artwork gets damaged in a commercial setting. Who should gallery employees call and when? Where does the responsibility lie? How are the works restored? How is their monetary value affected?

Artsy spoke to insurance brokers, lawyers, gallerists, a conservator, and an appraiser to understand what happens to a damaged work, and how it can find its way back to market with its value intact (or not).

How do works get damaged in the first place?

Judging from the news, you’d think the majority are ruined by careless visitors, with rambunctious children and selfie seekers as some of the most egregious offenders. In fact, these kinds of mishaps are fairly uncommon. Damage is usually caused during transit—in shipping, handling, and installation.

“My biggest worry is shipping,” said Louky Keijsers Koning, founder of the Lower East Side’s LMAKgallery. “A lot depends on how works are packed. Sometimes I’m surprised certain works arrive safely as packaged.”

Keijsers Koning remembered one specifically terrifying moment that took place a few years ago, when she received a glass-framed drawing from Europe that clearly had not been packed per her instructions. When the delivery person arrived, “I took the package and heard glass in the box,” she recalled. “The pieces of glass had torn the drawing in some spots. We spoke with the artist, who was a little bit devastated. Insurance took care of it, but the artwork was gone. And the next year, my premium went up.”

Anne Rappa, senior vice president at fine art insurance broker Huntington T. Block, said she has seen a wide range of shipping and handling problems over the years, from forklift damage (“It went directly through the canvas, which is always completely heartbreaking”) to crates containing artwork with dirty footprints on them. She also remembered the devastating effects of Hurricane Sandy, in which damage was caused not only by the corrosively salty, dirty water, but also by the strength of the waves, which caused floating objects to crash into valuable works. “It was the most imperfect of storms,” Rappa said, adding that it was the first time in her career that she’d had to handle multiple geographic locations impacted simultaneously, from Brooklyn to Long Island City to Chelsea.

Appraiser Victor Wiener said he has seen “water damage, fluids of all kinds, stains of unknown origin, lots of tears, and substances hitting the canvas.” During Hurricane Sandy, he recalls a work floating off to sea.

It’s damaged. Now what?

The first thing a gallery should do when a work is damaged is contact the owner of work if it’s a consigned piece, said Colin Quinn, director of claims management at AXA Art. The second step is to notify the insurance company, which will assign a conservator and send an adjuster to assess the damage. The conservator then creates a treatment proposal for the owner of the piece to approve before moving forward with conservation. Once the piece has been repaired, an appraiser assesses it for loss of value.

Suzanne Walsh, director of Salt Fine Art in Laguna Beach, California, said in her 10 years in the business, she’s only ever called insurance twice. Instead, she likes to work directly with the artist and see if they can find a solution together. “Things happen all the time,” she said. “The real problem is if you try to hide it and don’t take responsibility for it.” She added that there have been times when gallery employees and interns have damaged works, but that’s to be expected when one is moving dozens of works around every time a show goes up or down.

While Walsh likes to recruit the help of artists in fixing their own works whenever possible, in larger galleries, and in cases where the artist is no longer alive, a conservator is called to the rescue. Conservator Suzanne Siano has labored over many damaged works, primarily paintings, and at times, sculptures. Usually, it’s the galleries and auction houses that call her, but sometimes the insurance companies do, too.

“Sometimes a dent could be made to go away, but a tear, not so much,” Siano said, noting that even the most judicious restoration of a torn painting will still bear traces of the damage. Fixing tears in paintings involves either realigning broken threads and patching the canvas on the reverse, or, for a more invisible fix, meticulously reweaving the threads of the canvas under a microscope, which can take days or even weeks to accomplish.

Siano noted that even though there may be other wear and tear on a work that could require restoration, for damaged works, she is usually hired to only conserve the damage caused by the particular event, since that is all that is covered by insurance.

After documenting the damage and conserving the work, the appraiser will determine whether or not the work lost value in the process. (It’s helpful to have an evaluation both pre- and post-restoration.) Wiener said that he receives daily calls about appraising damaged and restored works. “Different clients have different needs,” he said, “but mostly they want to know the loss of value.” When Wiener gets called in to do an appraisal on a piece that’s just been damaged, he’ll also often recommend a restorer.

In appraising a work, Wiener said he takes into consideration a number of variables, particularly those outlined in the J. Paul Getty Trust’s Object ID, an international standard for describing cultural objects. Factors include the type of object, materials and techniques, measurements, inscriptions and markings, distinguishing features, title, subject, date, and artist. Wiener added that once the damaged work is restored, “the success or failure of the restoration is crucial.” (A restored work almost always loses value in comparison to the original, but a beautifully restored work tends to regain more value than one where the restoration job is more obvious.) Market tolerance and the rarity of a particular work are also of the utmost importance, as the value of a work that’s completely different from anything else a particular artist has made will have a “stronger tolerance to damage,” Wiener said.

The importance of documentation and contracts

“The most important thing to do after damage occurs is to preserve evidence,” attorney Wendy Lindstrom told Artsy. “Take photographs; save all pieces, crates, and/or packaging; create a record; prepare a report; take witness names and statements; immediately collect as much information about the damage and the tortfeasors [people responsible for the damage] as possible.”

Who pays for what is governed by contracts between consignor and consignee, lender and borrower, gallery and shipper and/or art handler, and purchaser and seller. The contracts ideally also lay out how damage incidents are handled and whose insurance will cover the loss.

When something goes awry

In a perfect world, a damaged artwork is restored, reappraised, and then goes back on the market as soon as possible. Of course, the process isn’t always so smooth. Sometimes the work is simply beyond repair—a “total loss” in insurance policy terms. In these cases, when the damage to the work costs more to repair than its total value, the insurance company pays out the full value, acquires the work, and sells it as “salvage,” explained Mary Pontillo, Senior Vice President and National Fine Art Practice Leader at insurance brokerage firm DeWitt Stern/Risk Strategies. The concept is similar to when a car insurance company determines a car is totalled after an accident, acquires it, and sells it for parts.

(Oddly enough, the totalled artwork sometimes finds its way back on display. For example, working with AXA’s collection of salvage, the Salvage Art Institute puts on travelling shows of these works of “zombie art,” the most recent of which closed in Munich in February.)

Another problem can sometimes arise when the artist isn’t informed of the damage and later disapproves of the conservation job. Whether or not the artist or artist estate works with conservators in situations of damaged works largely depends on their contracts with the gallery. “Once the artist is involved, we have to respect the artist’s feelings,” Siano said, adding that, as should be expected, some artists are more cooperative than others. The most unpleasant cases for everyone involved are when artists disavow restored works under the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA), maintaining the conservation completely changed the work, as

did last year, suing a collector, art adviser, and two galleries for restoring Log Cabin(1990) without her permission.

Other legal disputes can arise. When multiple appraisers are hired to evaluate a work after conservation, they sometimes disagree on the new value of the piece, for example. Perhaps the most well-known of these was a case of differing appraisals of a damaged

triptych, The Chicago Seven, September 25th, 1969 (1969), a disagreement that lasted for years and made it all the way to the New York State Supreme Court. Two appraisers came up with completely different views of the value of the work after it sustained water damage from a leaky pipe. One appraiser concluded the work had “virtually no commercial value due to obvious undulations and tide marks on the bottom half of one panel,” according to artnet News’sAlexandra Peers, while the other appraiser didn't see the damage as dire at all, using “various formulas that involve, among other measures, the percentage of the canvas damaged.” Although he didn’t want to comment on the Avedon case specifically, Wiener said it was “not uncommon” for appraisers to come up with different numbers.

Although damaged works tend to lose value, on rare occasions, the publicity of restoring the work paradoxically can have the opposite effect. Wiener cited

’s Salvator Mundi (c. 1500) as a prime example of this phenomenon, which he largely attributed to the high-quality restorative work of Dianne Dwyer Modestini, senior research fellow and paintings conservator at New York University’s Conservation Center.

On a more personal note, Wiener said he appraised

’s Le Rêve (1932) — the painting that was famously a victim of Steve Wynn’s elbowseveral years ago and sold for $155 million in a private transaction after restoration — right before restoration was finished. (He declined to share the number he came up with.) Again, the quality of the restoration was certainly a factor in the painting’s final valuation, but there were a couple other factors at play, including the amount of press the whole elbow incident received and, perhaps most notably, the fame and uniqueness of the painting itself. Wiener said that the increased value of the painting “was partly because of publicity, yes, but also because it’s one of Picasso’s greatest paintings. What are the chances of another Picasso like that coming along?”

So what’s the lesson to be learned from all this? While damaging artwork should always be avoided, if you happen to be a billionaire collector and damage your very famous painting in a very clumsy way (not on purpose, of course), make sure to hire the best conservator and tell the media all about it. Who knows? The painting might even gain value in the process.

Elena Goukassian

English Art Terms You Should Know

The words we use to talk about art can often seem opaque—and not just when they take the form of foreign languages like French and German. Yet this lexicon is an invaluable tool to have in your arsenal when thinking about and analyzing art. With roots in far-flung historical moments and art movements, the following eight English art terms will set you well on your way to discussing all kinds of art like a pro.

Canon (Canonical)

Differing little in spelling but significantly in meaning from its double-N homophone “cannon,” “canon” comes from the Greek word kanōn, meaning a measuring rod, rule, or model. The term was first used within the context of Christianity to refer to the faith’s accepted guidelines and, later, to official, church-decreed regulations. As early as the fourth century A.D., the parts of the Bible that were considered to be the word of God were deemed to be of the canon, or canonical.

Over time, the concept of a canon expanded to a wide range of fields, from literature, film, and music to philosophy and even geography. Today, it generally refers to the established works, individuals, or theories that form the historical backbone of a particular discipline or genre. Spanning from antiquity through the contemporary era, canonized artworks are generally privileged in art history courses, museum exhibitions, and other art world institutions—venerated as exemplars of the movements they represent, and of art historical progression.

The canon has received its fair share of criticism for prioritizing Western art created by white males, with scholarly efforts emerging at the end of the 20th century to critically assess and broaden it. In addition to the overarching art historical canon, individual artistic movements or national traditions may be said to have their own canons.

Painterly

“Painterly” art is characterized by visible brushstrokes that evidence the hand of the artist and call attention to the nature of the artwork—in other words, to its paintingness. Painterly work is looser and less tightly controlled, contrasting with linear work, which is defined by discrete outlines and borders, as well as smooth, inconspicuous paint application. Linear painting took center stage during the

, when an interest in creating the illusion of three-dimensional space flourished—though Venetians

and

, among others, also celebrated a painterly technique with expressive, unpolished brushstrokes.

In the centuries that followed, artists who advanced a painterly approach proliferated, from

painters like

, to

like

and

, to

.

“Painterly” need not apply only to paintings; it can also describe elements of works in other mediums that suggest a painted quality. In photography, for example, such works abounded in the 19th-century

movement, whose practitioners aimed to elevate the status of their fledgling medium by making their images resemble paintings through atmospheric colors, hazy forms, and surface brush marks.

Figurative

The adjective “

” is applied to artworks that contain identifiable, real-world subjects, often (but not necessarily) including the human figure. Most, if not all, Western art created prior to the birth of modernism—which championed abstraction—represents the physical world, and can thus be described as figurative. Called “figuration” in noun form and often termed “representation” or “representational art,” figurative art was dismissed throughout most of the 20th century as artists pursued what they saw as the higher, universal language of abstraction.

Despite that move away from figuration, artists like

and

continued to make figurative art in the mid-to-late 20th century, and

helped to revive an appreciation for it

. In the past decade, the art world has seen another resurgence in the popularity of figurative painting, especially in work that takes an unconventional approach or reflects upon social realities—like that of

,

,

, and

, to name just a few.

Notably, figurative art includes—but is not limited to—realism. Photorealists like

and

hold down one end of the spectrum, while

and

painted figures that are significantly abstracted from reality, yet still include recognizable forms.

Foreshortening

Andrea Mantegna

Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan

Beginning in the 15th century, during the early Italian Renaissance, artists like

sought a convincing way to depict three-dimensional objects in a two-dimensional artwork. Their solution was foreshortening, a technique that is still ubiquitous today, in which the artist adjusts the scale of an object’s parts to convey variations of depth within the picture plane.

Perhaps the most famous case of foreshortening is the depiction of Jesus in The Dead Christ (ca. 1480) by

, who was a preeminent innovator of the technique. By making the subject’s feet larger and his head smaller, as well as by shortening his limbs and body, the artist created the illusion of the body receding backward. Often, the foreshortened effect is not quite true-to-life, but that’s intentional—the artist makes the difference in size less extreme, so that the nearest part of the foreshortened object does not overwhelm the composition or block the farther part.

In addition to portraits, foreshortening also appears in still lifes, landscapes (such as with a road that winds away from the viewer), and Renaissance frescoes (often used for the representation of architectural elements) by the likes of

,

, and

. More recently,

achieved virtuoso foreshortening in his Reclining Figure(1994).

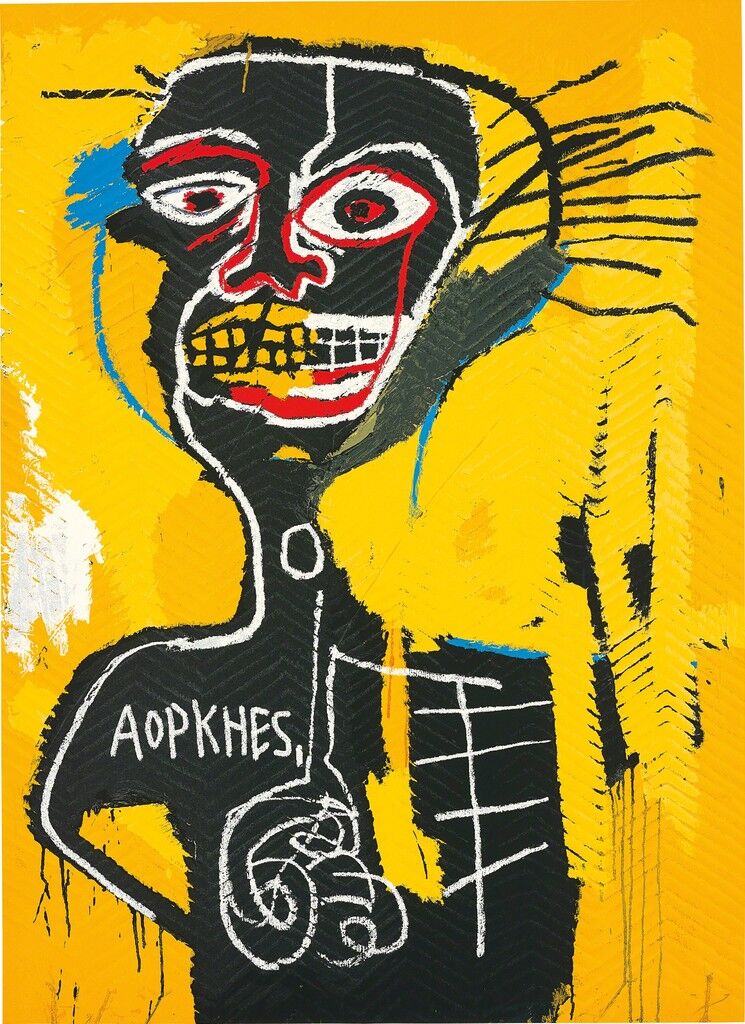

Gestural

In his seminal 1970 book The Triumph of American Painting: A History of Abstract Expressionism, art historian and critic Irving Sandler coined the terms “gesture painters” and “color field painters” to describe the two distinct branches of

. With artists like

and

in the latter contingent,

epitomized gesture painting. Pollock insisted on gesture, or the action of painting, not only as process, but as the primary content of his finished work, while critics read his drips and splatters of paint as outward manifestations of his psyche.

Although it is rooted in this particular moment in art history, the term

has come to apply more broadly to any artwork whose dynamic and sweeping strokes, pencil marks, or sculptural modeling reveal the act of the work’s creation, often with an element of perceived informality, spontaneity, abandon, or emotional intensity. While examples of gestural artwork abound throughout art history—from

to Van Gogh’s swirling landscapes—contemporary artists whose works feature gestural elements include Basquiat,

, and

, among many others.

Participatory

From

’s piles of paper or candy that visitors can take, to

’s installations that light up in response to viewers’ fingerprints and heartbeats, to

’s silent staring contests, “participatory” art depends on the viewer in order to be fully realized. A descendent of

, which relied on an audience’s reactions to intentionally outlandish speech, costumes, and props, participatory art can also trace its roots back to

’s 1960s

, which involved guests in immersive, choreographed experiences.

In the same vein as

, participatory art covers a wide range of practices and motivations. Some artists call attention to participants’ sensory experiences and interpersonal interactions, as with

’s 1968 Dialogue: Goggles—in which two volunteers look at each other through distorting lenses—or the meals that

cooks for gallery visitors. Other participatory works, like

’s performances, are based in social activism and community engagement. Nearly all participatory art, however, challenges the traditional artist-viewer relationship and the position of the artist as sole author, as well as the nature of an artwork as a static finished object.

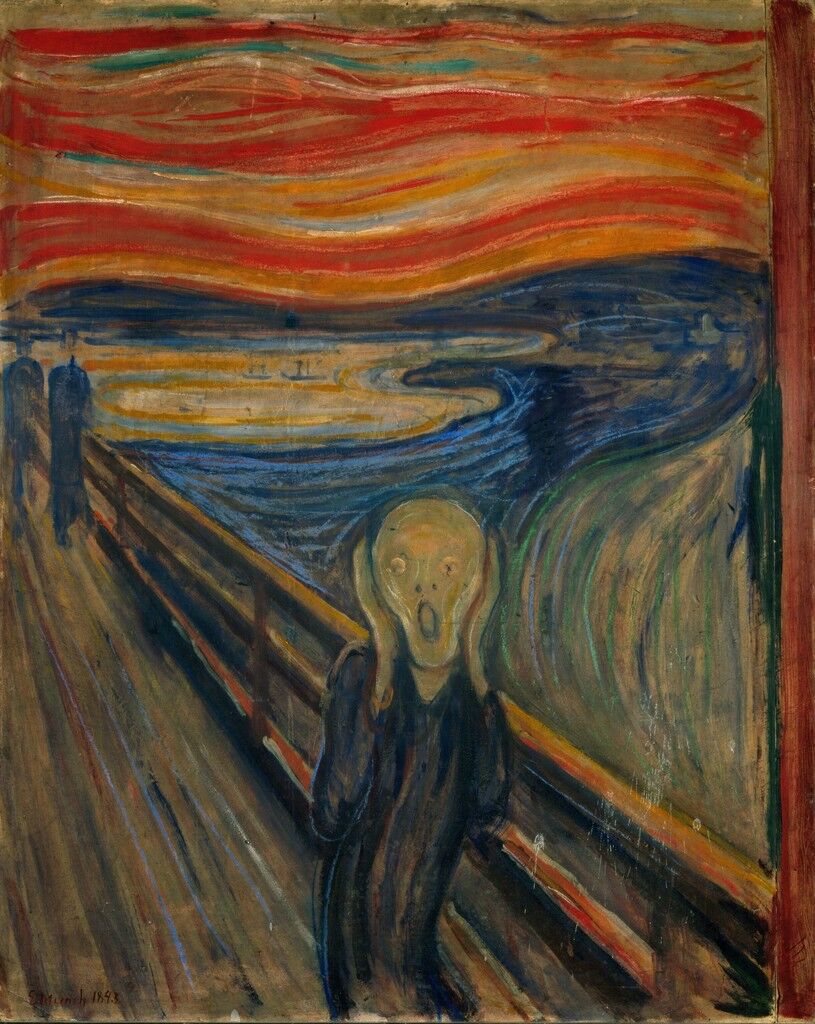

Masterpiece

Edvard Munch

The Scream, 1893

National Gallery, Oslo

Johannes Vermeer

Girl with a Pearl Earring, ca. 1665

Mauritshuis, The Hague

Google variations of “masterpieces in art” and your search will return numerous articles that purport to list the most famous or greatest works of art across history. Artworks considered masterpieces are often undeniably impressive in their own right—virtuosic works that display both the talent and skill of their makers in terms of color, composition, inventiveness, or sheer labor. However, the pieces deemed worthy of this recognition are also intimately related to the art historical canon; for decades and even centuries, they have been written about, displayed, and fawned over, taking on a near-mythical significance.

Although it is still widely used, in recent decades, the term has been critiqued by some scholars for perpetuating a tradition that is overwhelmingly Western, white, and male. Not only did “master” necessarily refer to a man, but the word still refers almost exclusively to male artists who are recognized as having advanced the Western tradition, as in

or contemporary master. Some scholars similarly take issue with the term “masterpiece” for being based in mere renown, rather than in critical evaluation.

Historically, however, a “masterpiece” was a more objective designation. Borrowed from the Dutch meesterstuk and the German Meisterstück, the word literally referred to a piece that an artisan submitted to his guild to become a master of his craft. After attaining this superlative classification, he could pursue his trade without supervision and teach others. With attention to factors like originality and authenticity, connoisseurs and art historians later helped shift the definition of the word toward its current iteration.

Biennial / Triennial

The French Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. Photo by Casey Kelbaugh for Artsy.

Emerging in the early 1600s, the word “biennial” derives from the Latin words bi, meaning “twice,” and annus, meaning “year.” Not to be confused with “biannual,” which refers to twice-yearly occurrences, “biennial” applies to those events that happen every other year, and can be used as both a noun and an adjective.

In noun form, and in art world terms, a biennial is a large art exhibition that takes place once every two years and surveys recent work from the host region or country, or further afield. The Venice Biennale (biennale is “biennial” in Italian)—founded in 1895—is traditionally considered the origin of the modern biennial and still stands apart in its size, scope (last year’s edition featured 83 national pavilions), and prestige; it is often referred to simply as “The Biennale.”

Biennials have recently exploded in number and continue to spread around the globe, with Latvia’s Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (RIBOCA) and the Bangkok Art Biennale in Thailand having both launched this year. Triennials—which range from the New MuseumTriennial in New York City to the Garage Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art in Moscow—are versions that take place every three years, from tri, meaning “three.”

Compared with art fairs, biennials and triennials (as well as quadrennials and quinquennials, which occur every four and five years, respectively) are less commercial, and generally focus instead on celebrating artistic innovation and fostering critical dialogues.

Rachel Lebowitz

Bold Voices

Stefan Sagmeister: What is Happiness

SPONSORED BY BMW

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)