Words, like many other items of exchange, swoop in and out of fashion. Some become useful staples. Some flourish and become over-familiar. Others are plundered from one arena and deployed in another, bringing with them worrying associations (as a friend recently messaged the fashion world at large: “stop launching and dropping things in 2017”).

Below is a shortlist of words that we feel have endured overexposure, and even abuse, in the art world in 2016.

Here’s to a happy retirement, one and all!

1. /activist

(As in: actor/ activist; musician/ activist; artist/ activist…)

Changing your Facebook status to reflect the cause du jour may well suggest that you are engaged with current affairs and possibly even a lovely human being, but it does not make you an activist (or even an “/activist”). It’s notable that the most long-term, politically engaged artists we’ve spoken to this year have tended to reject the term for themselves, instead reserving it for those who make activism their life’s work. Dishonorable mention here goes to all those in the British art world /activists who took to social media to counsel peace and love as reasons to #remain in Europe, and then filled the same feeds with bile and invectives the morning after #Brexit.

In the press material, Swizz Beatz’s “No commission” art fair sought to “activate” artworks, audience, and space. Courtesy No Commission

2. Activation

We’re not even sure what an “activation” is, but we’ve been invited to attend a few this year. While we imagine it’s meant to sound dynamic in a kind of Tracy Island way (“It’s time to activate the art world Scott!,””Roger that, Virgil! Thunderbirds are go!”) it somehow makes us think of those packs of activated seeds and nuts sold for $20 a pop to raw food vegans. Do you want an art world populated with the human equivalent of a small, overpriced pack of moistened almonds? No, you do not.

3. Carefully

As in “carefully selected,” “carefully put together,” “carefully curated.” If you’ve been given the job of selecting, putting together or curating something, we’d say that doing it carefully is pretty much the bare minimum, expectation-wise. Telling us that you’ve done it carefully is like soliciting praise for not wolfing hash brownies on the job, or failing to drop a vase on the floor. Also, we’re reasonably confident that “carefully curated” is a tautology.

Donna Huanca, “Surrogate Painteen” (2016). Courtesy Peres Projects. Photo: Adrian Parvulescu, Berlin.

4. Continuously

“The installation changes continuously.” “Participants continuously attended workshops.” Does it? Did they? Or did the installation change a few times over the course of the show, and the participants attend a series of workshops? Cheese, wine, and humans change continuously: not always for the best.

5. Emerging

You can see the appeal here. Fair play: it’s a non-ageist way to describe an artist whose work is starting to receive noteworthy attention. Yet “emerging” brings attendant suggestions of darkness and light, as if said artist had hunkered down in a dank cave halfway up a cliff and was finally planning to step out into the radiance of art world attention.

Moreover, it makes art world attention sound like some kind of nourishing benediction. Rather than, for example, the neon glare of the beachfront sports bars that lured confused turtle hatchlings to their sticky doom on a busy coastal strip at the end of Planet Earth II, which some might argue is closer to the truth.

Jeff Koons and Larry Gagosian at the French Institute Alliance Francaise’s Trophee des Arts Gala. Courtesy of photographer Sylvain Gaboury ©Patrick McMullan.

6. Famous

If an artist is genuinely famous, it’s likely we’ll have heard of them. Ditto an artwork or piece of writing. This is not boasting: we’re more or less oblivious to reality stars, can’t identify famous YouTubers, and more or less unlikely to trouble celebrity sportspeople with selfie requests, but artists? If we’ve not heard of them, it would suggest that they’re probably not that famous. They might be acclaimed, respected, award-winning, unfairly overlooked, or even, god-forbid, emerging. They might even be popular, or endorsed by celebrities. But fame? That brings its own proof. If you feel the need to mention it, you’re already over-egging the pudding.

7. Iconic

It’s fine: we get that “iconic” no longer pertains to religious paintings. But when applied to people, it should suggest that they are in some way representative of their time or an idea: something larger than themselves. Rather than meaning “person who has allowed themselves to be photographed a lot,” “artwork that has received many likes on Instagram,” or “popular consumer item.”

Eliza Douglas in Anne Imhof, Angst II (2016) at the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin. Photo ©Nadine Fraczkowski.

8. Immersive

Overexposed. If you’ve used this twice in a paragraph, you’re probably using it too much. Pull back. Grab a thesaurus.

9. Interrogate

The use of artworks to interrogate ideas seems cruel and unnecessary to both parties involved. Just think of all those poor, beautifully-formed concepts being forced to sit through looped three screen video installations with binaural sound until they crumble and ‘fess up. It makes us come over all snuffly.

10. Intervention

Seems to have become a more forceful alternative to “site specific installation.” Just as “activate” feels like it was borrowed from a paleo diet plan, “intervention” has a whiff of therapy to it, as if the artwork were a concerned family trying to come between an alcoholic and a bottle of cash-and-carry whisky. Whether than makes the audience the whisky or the auntie about to be placed in a residential twelve step program, we leave you to decide.

The work of 2016 Turner Prize winner Helen Marten has been described as “poetic” by the jury. Photo Danny Lawson/PA Wire.

11. PoeticPoetry—that stuff that can haunt and tease and trouble your soul—is a natural ally to visual art, (see: Etel Adnan,

Marcel Broodthaers, Dante Gabrielle Rosetti et al.) As an adjective, however, “poetic” has become lazy critical shorthand for “it looks great, I don’t understand it, and I can’t really be bothered to try.”

12. Transformative

The process of developing an exhibition or body of work may very well have been transformative for the artist, but to describe that work in itself as transformative is heady stuff. It suggests the visit to an exhibition as perhaps akin to undertaking a pilgrimage: a journey of change and self-discovery. Sometimes it is, sometimes it isn’t. Usually in the case of exhibitions that describe themselves as “transformative,” it’s the latter.

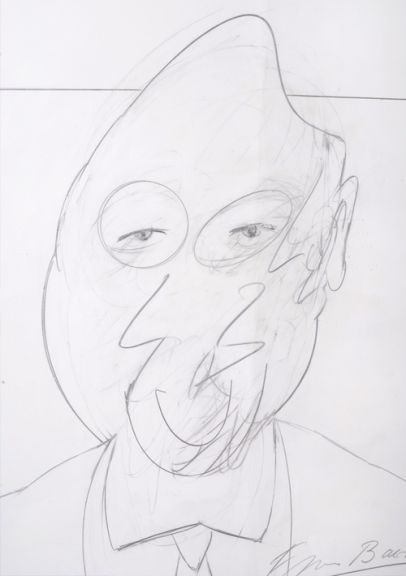

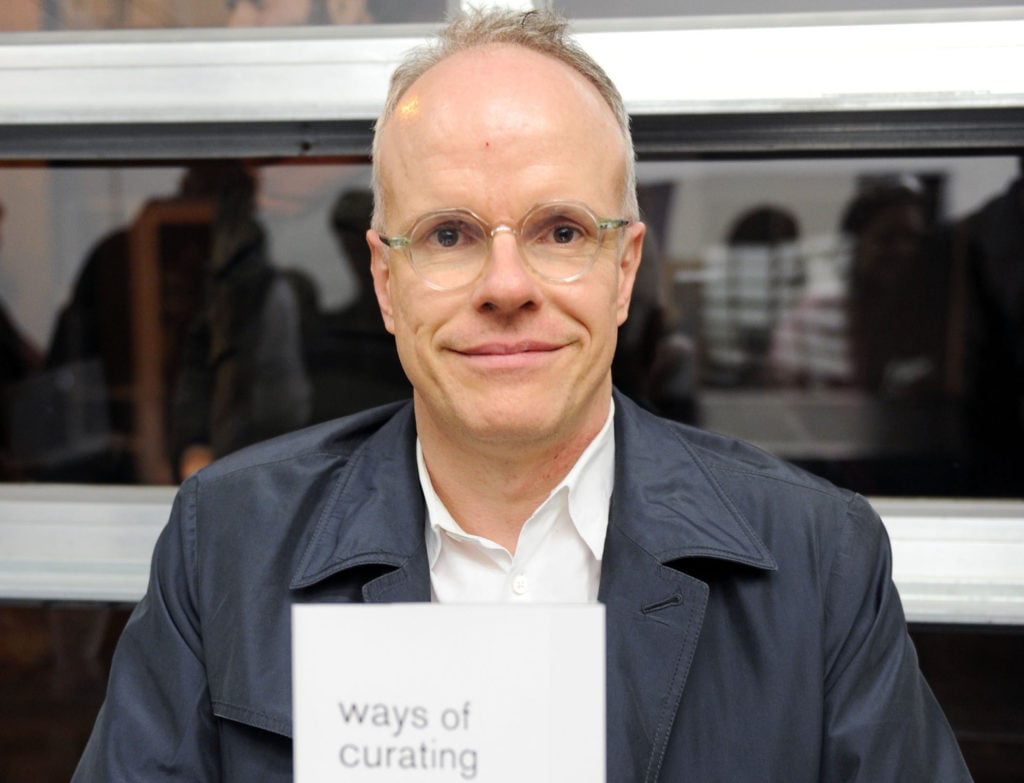

Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist is a fan of the word “urgent.” Photo Craig Barritt/Getty Images for Surface Magazine.

13. Urgency

Remember how people used to describe things as “relevant” in the 1970s? Urgency seems to have taken its place, denoting something very “now” and worthy of your attention. “Urgency” inevitably seems to be applied to –ologies and –isms, which is grammatically irksome. Also, in this month of icy northern winds, “urgency” makes us think of needing to pee.

Follow artnet News on Facebook.