Visual Culture

Unpacking Fashion’s Love Affair with Artists

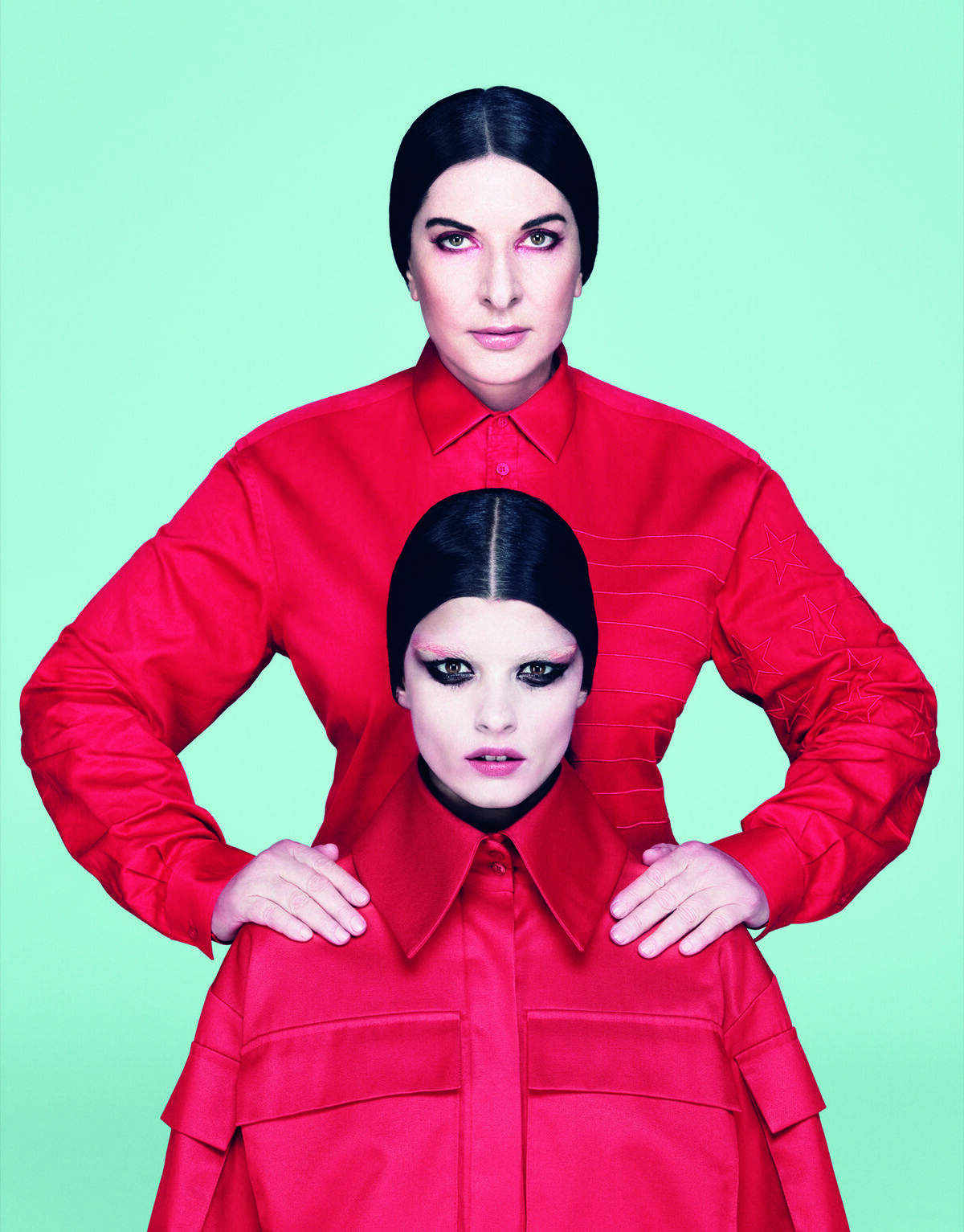

Dusan Reljin, Marina Abramović and Crystal Renn for Vogue Ukraine, 2014, from “Legendary Artists and the Clothes They Wore,” 2019. Courtesy of Harper Collins.

Why do we care what famous artists wear? It might seem silly to look back to the

to appreciate their outfits, but 20th- and 21st-century artists have often found themselves the muses of major fashion houses—and, more recently, fodder for Pinterest inspiration boards. Artists, after all, are keenly considerate of color and form; how they dress can be a telling sign of their creative innerworkings.

“The job of artists is to critique culture, unload their psyches into their work, and make edifying masterpieces the rest of us can revere,” wrote Terry Newman, author of Legendary Artists and the Clothes They Wore (2019). “What they wear while doing these things is interesting, too.” Newman’s book dissects the fashion choices of major artists and traces how their art and personal style has been appropriated or emulated on runways and in wider visual culture.

A model is seen ahead of the Raf Simons fashion show during Pitti 90, Florence, Italy, 2016. Photo by Antonello Trio via Getty Images.

Fashion houses often pay homage to famous artworks and movements—Moschino under Jeremy Scott’s direction heavily references

—but they’ve also tried to capture that ineffable je ne sais quois of the artists behind the works.

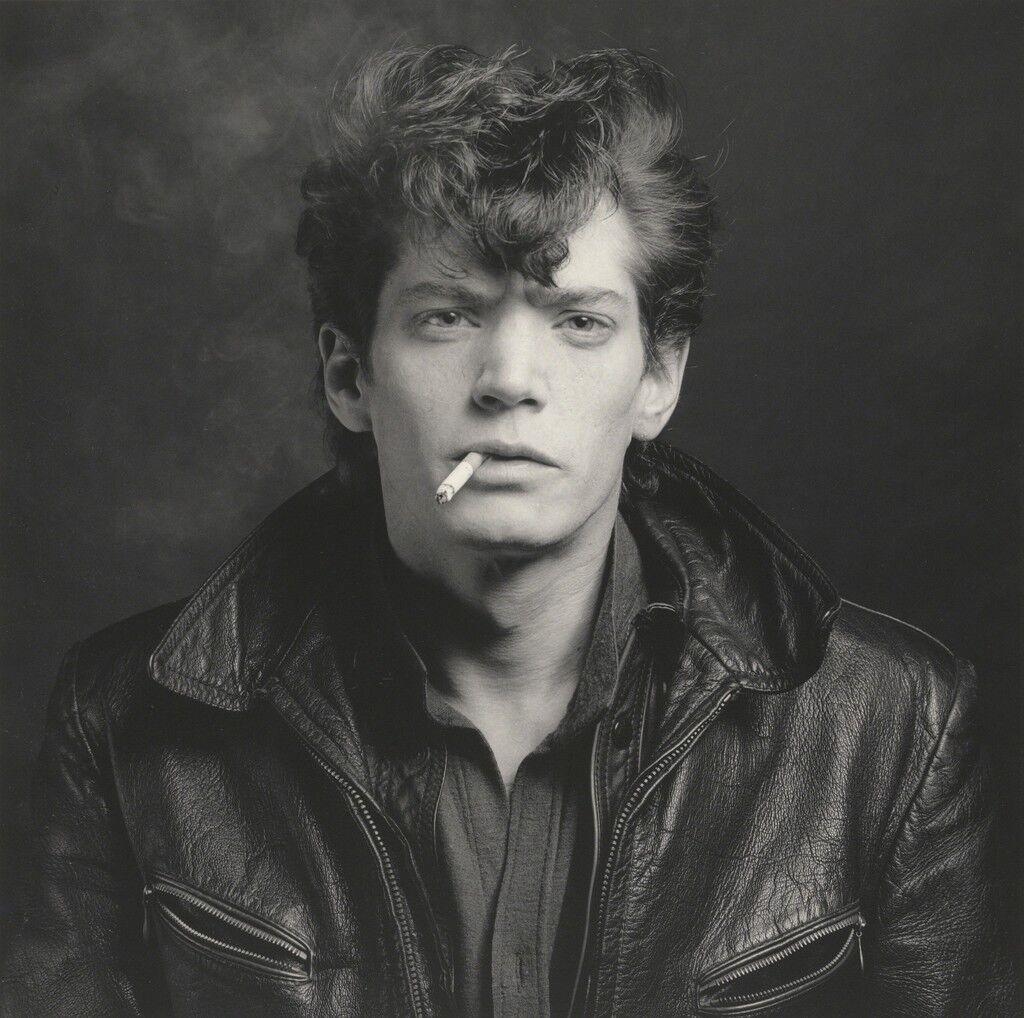

did both in his 2017 spring menswear collection, a collaboration with the

Foundation. The male models wore billowing button-down shirts printed with Mapplethorpe’s black-and-white photographs. They were also styled to look like the late artist, with soft, curly hair and leather muir caps—an ode to Mapplethorpe’s personal and artistic interest in S&M. The looks bring to mind former Interview editor Bob Colacello’s recollection of the photographer when they met in 1971: “He was pretty but tough, androgynous and butch,” Colacello told Vanity Fair in 2016.

The inspiration for the autumn 2014 Céline show was more precise: the muddy, masculine boots of war photographer

, from the famous image of her sitting defiantly in Adolf Hitler’s bathtub just hours before his death. Miller’s streamlined, “utility chic” wardrobe, as Newman called it, which she wore while on assignment for Vogue during World War II, has been referenced in fashion multiple times. But designer Phoebe Philo specifically named Miller’s boots as the starting point for the collection. “[Miller was] doing things which were quite radical at the time, like wearing men’s clothes, but which today seem quite normal,” Philo said after the show.

A model walks the runway at the Celine Autumn Winter fashion show during Paris Fashion Week, 2014. Photo by Catwalking/Getty Images.

Artists’ personal style, intentionally or not, often becomes part of their brand. Some artists channel their visual aesthetic into their looks.

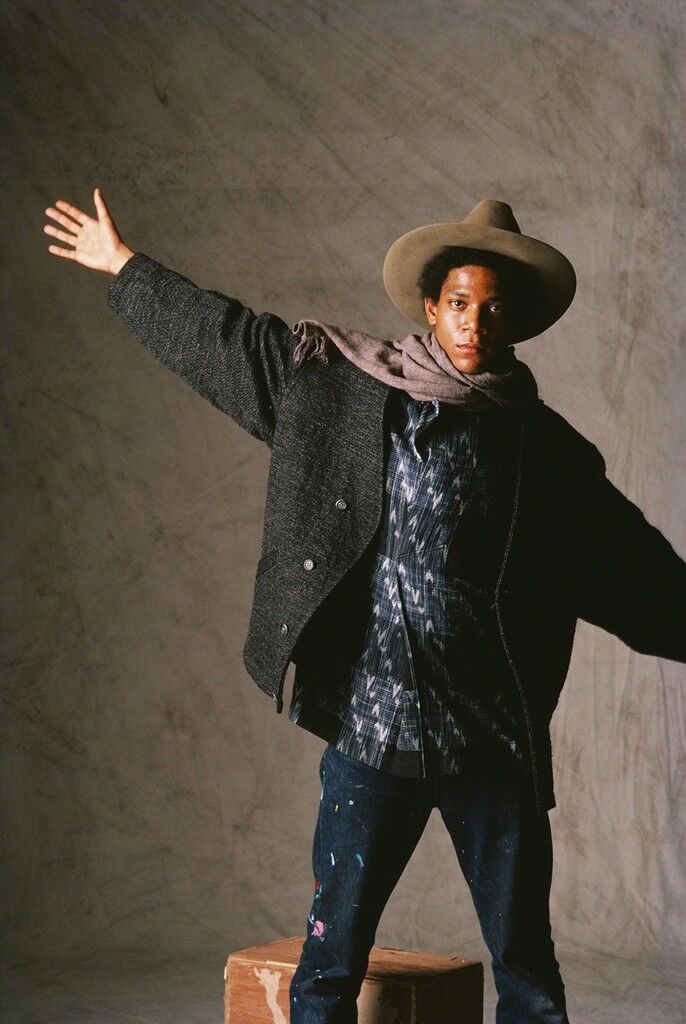

paired designer suit jackets with worn-in streetwear,

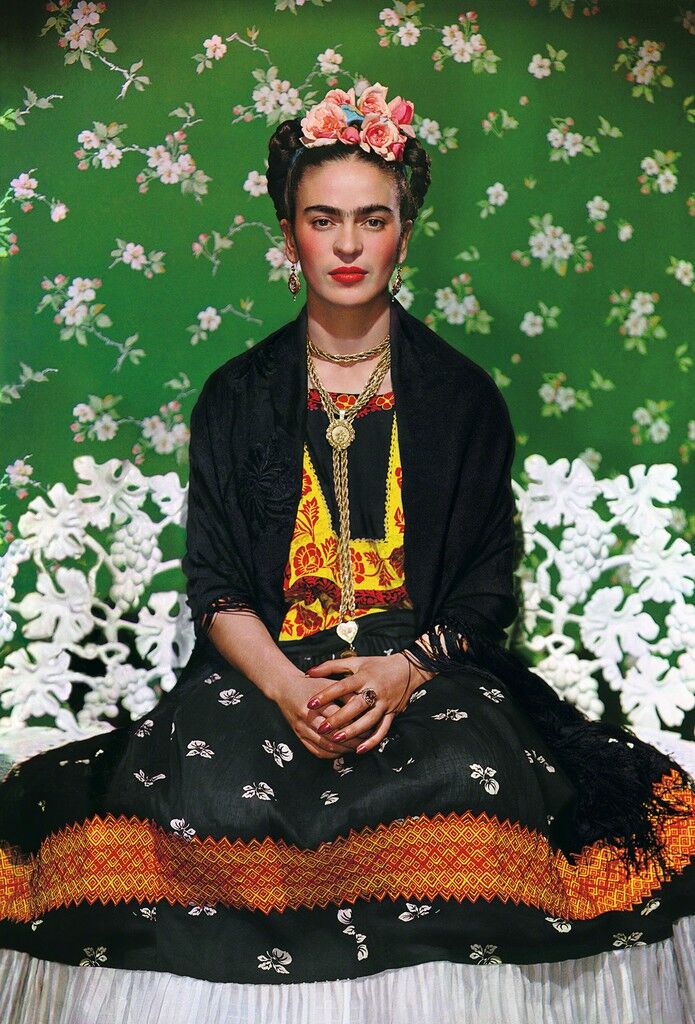

wore traditional Mexican garb rife with symbolism, and

opted for minimal silhouettes with Southwestern accessories. Likewise,

is known to sport vivid, color-blocked outfits. Designer Christopher Bailey, formerly of Burberry, is a self-professed fan: “I love the way Hockney wears color,” he has said, “so that you’re never completely sure how deliberately the look is put together.”

Others resist fashion trends, a statement in itself. Today,

outfits herself in haute couture but as a young artist, she carefully crafted her image as “very radical, no make-up, tough, spiritual,” as she told Vogue in 2005. In the 1970s, she explained, being fashionable as an artist could be construed as overcompensating for a lack of talent.

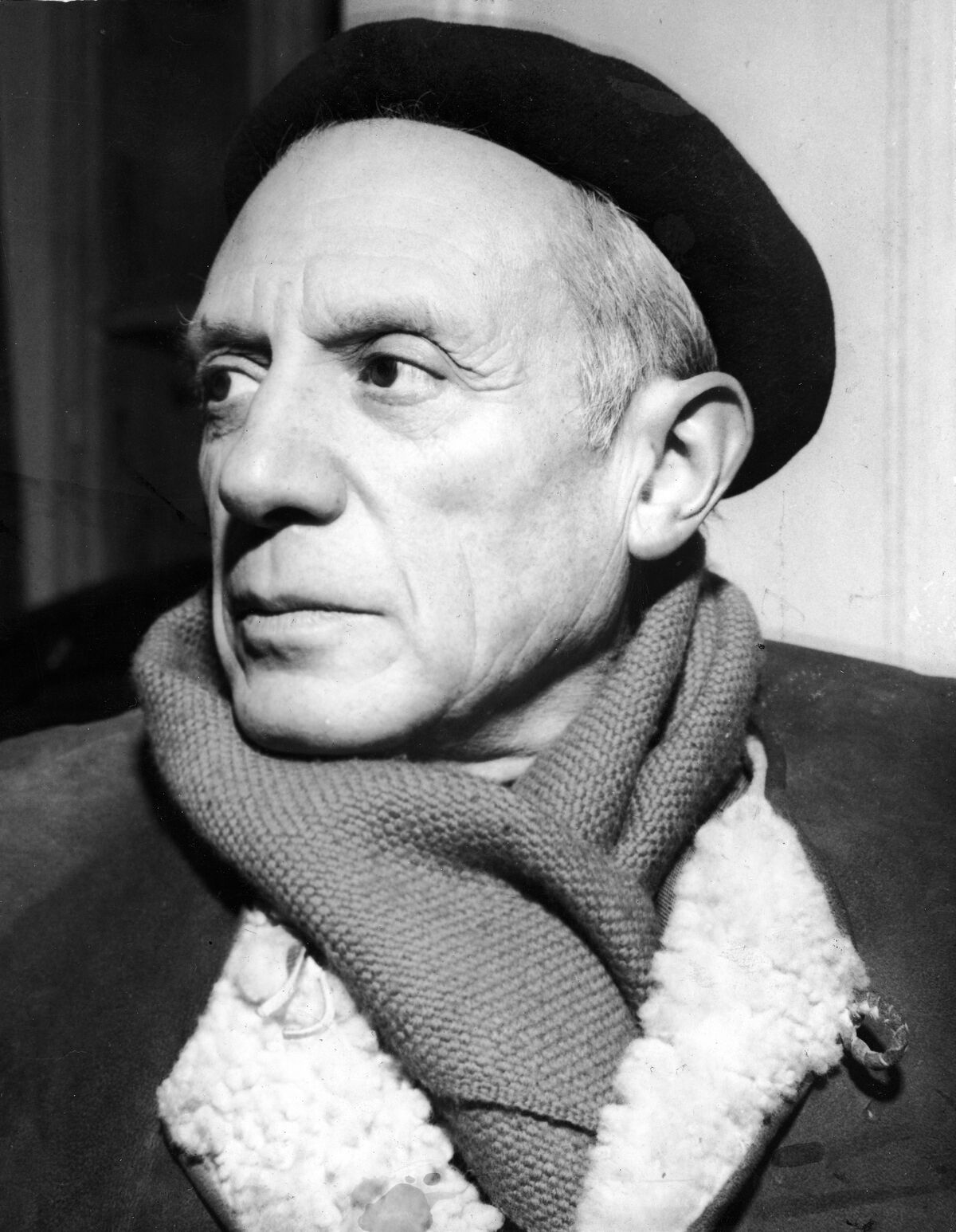

Portrait of Pablo Picasso in a winter coat, scarf, and beret, ca. 1950s. Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Over time, and with the repetition of a look, some artists have successfully whittled down their personal style into a single icon. Think of

’s bowler hat or

’s bright red bob. Although Pablo Picasso was known to wear various types of hats—“Peruvian knitted hats with pom-poms, sun-shielding straw toppers, and stiff, classy homburgs,” Newman noted—it was his beret, frequently featured in his paintings, that stuck. His status as a style influencer was made clear during two of his exhibitions at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art in the 1950s: “Employees found lost berets more than any other personal item,” Newman wrote.

Some artists have influenced contemporary fashion more directly, lending their expertise to fashion houses and retail lines. In 1983, Malcolm McClaren and

tapped

to translate his street art into fluorescent streetwear for the runway. Kusama produced a collection for Bloomingdales in the 1980s and has more recently collaborated with

and

.

has also collaborated with Louis Vuitton, as well as H&M and Stella McCartney.

Wax figure of Japanese artist, Yayoi Kusama at the Louis Vuitton and Yayoi Kusama Collaboration Unveiling at Louis Vuitton Maison on Fifth Avenue, New York, 2012. Photo by Rob Kim/FilmMagic.

It’s after artists’ deaths, however, when their style can be merchandised to such an extent that it becomes disconnected from the reality of their lives.

, who once designed utilitarian-wear for a utopian Russia, would have balked at Jerry Hall modeling high-end red garments for a 1975 British Vogue editorial inspired by his graphic, Communist-flavored works. Basquiat embraced the fashion world and was loved by designers, but he faced racial bias as a black man shopping for expensive clothes. He modeled for

and favored Armani and

, but according to his late girlfriend Kelle Inman, he was often tailed in department stores, and once was denied entry to high-end boutique until he returned with Inman. Three decades later, Basquiat’s brand is packaged into lines from Forever 21, Sephora, and Douglas Hannant.

Norman Parkinson, Jerry Hall Rodchenko, from “Legendary Artists and the Clothes They Wore,” 2019.Courtesy of Harper Collins.

The commodification of Kahlo’s style is perhaps the most glaring example. She is revered for her fashion, which is intrinsic to her art—she appeared in her many self-portraits wearing embroidered huipil blouses, Juchiteca headdresses, and full skirts; and accessorized with flowers, gemstones, and plaited hair. Kahlo’s fashion choices were tied directly to her heritage and her disability; she hid her prosthetic leg in a red leather boot adorned with two bells. Art historian Hayden Herrera said when Kahlo “put on the Tehuana costume, she was choosing a new identity, and she did it with all the fervor of a nun taking the veil.”

Kahlo’s wardrobe and accessories, representing the deepest layers of her identity, have been translated again and again: by Christian Lacroix in 2002, Gaultier in 2004, Commes de Garçons in 2012, and even Barbie in 2018. You can find her face on nearly anything: There are Frida pins, Frida T-shirts, Frida nailpolish, Frida bracelets (like the one British Prime Minister Theresa May wore in 2017, sparking endless news analysis). Kahlo’s clothing, which was kept under lock and key for nearly 60 years at her husband

’s request, has now been the subject of blockbuster exhibitions.

A Pakistani model presents a creation by Deepak Perwani on the second day of Fashion Pakistan Week, Karachi, 2013. Photo by Asif Hassan/AFP/Getty Images.

Perhaps fashion is more cyclical than art, or simply runs on a shorter cycle, repeatedly revisiting and retranslating trends. Artists, willingly or not, are pulled into that rotation, as inspiration. In 1967, photographer

traveled to O’Keeffe’s home in New Mexico to capture her for a story in Vogue. The then 79-year-old artist had spent a lifetime carefully crafting her image, wearing elegant but simple silhouettes accented with turquoise and silver accessories. In 2009, actress Charlize Theron flew to the late artist’s home with photographer

to recreate the shoot, marking another turn in the rotation of O’Keeffe’s influence.

Two years later, Abramović made the influence of fashion on art clear when she asked Italian designer Riccardo Tisci to suckle on her breast in another shoot with Testino, this time for Visionaire. The pair, who are friends and collaborators, commented on the images for the issue. “I said to him, this is the situation: Do you admit fashion is inspired by art?” Abramović recalled. “Well, I am the art, you are the fashion, now suck my tits!” The image of the performance artist feeding Tisci like a baby may be an odd—and oddly literal—visual metaphor, but when art nurtures fashion it trickles down to the rest of us, a small piece of an artist’s oeuvre hanging in our own closets.

Jacqui Palumbo is a Senior Editor at Artsy.