and again

one more time

idem

and again

take me to the next hospital

|\| ART BLOG HUMOR BLOG PHOTO BLOG CULTURE BLOG |:| FOR THE RENAISSANCE MAN & THE POLYMATH WOMAN |/|

one more time

idem

and again

take me to the next hospital

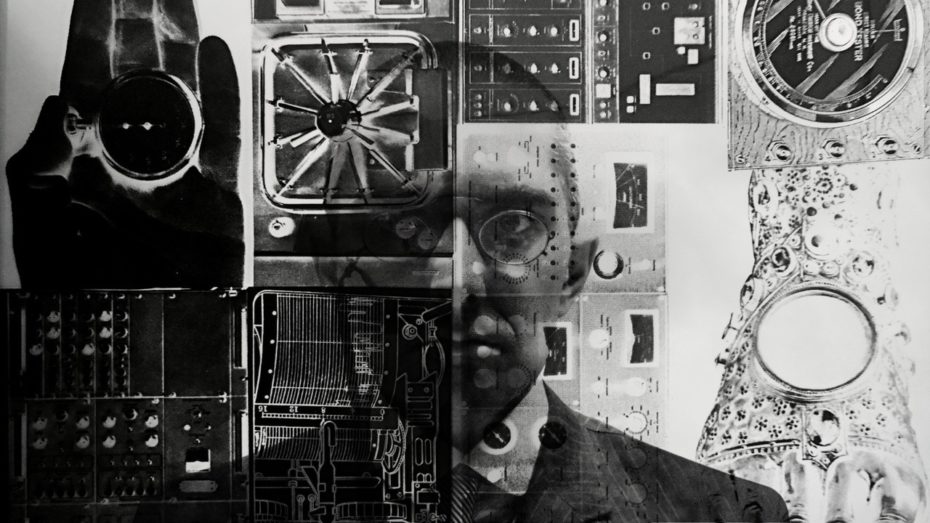

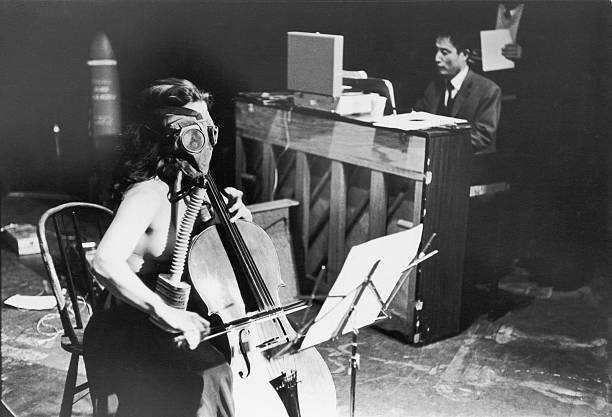

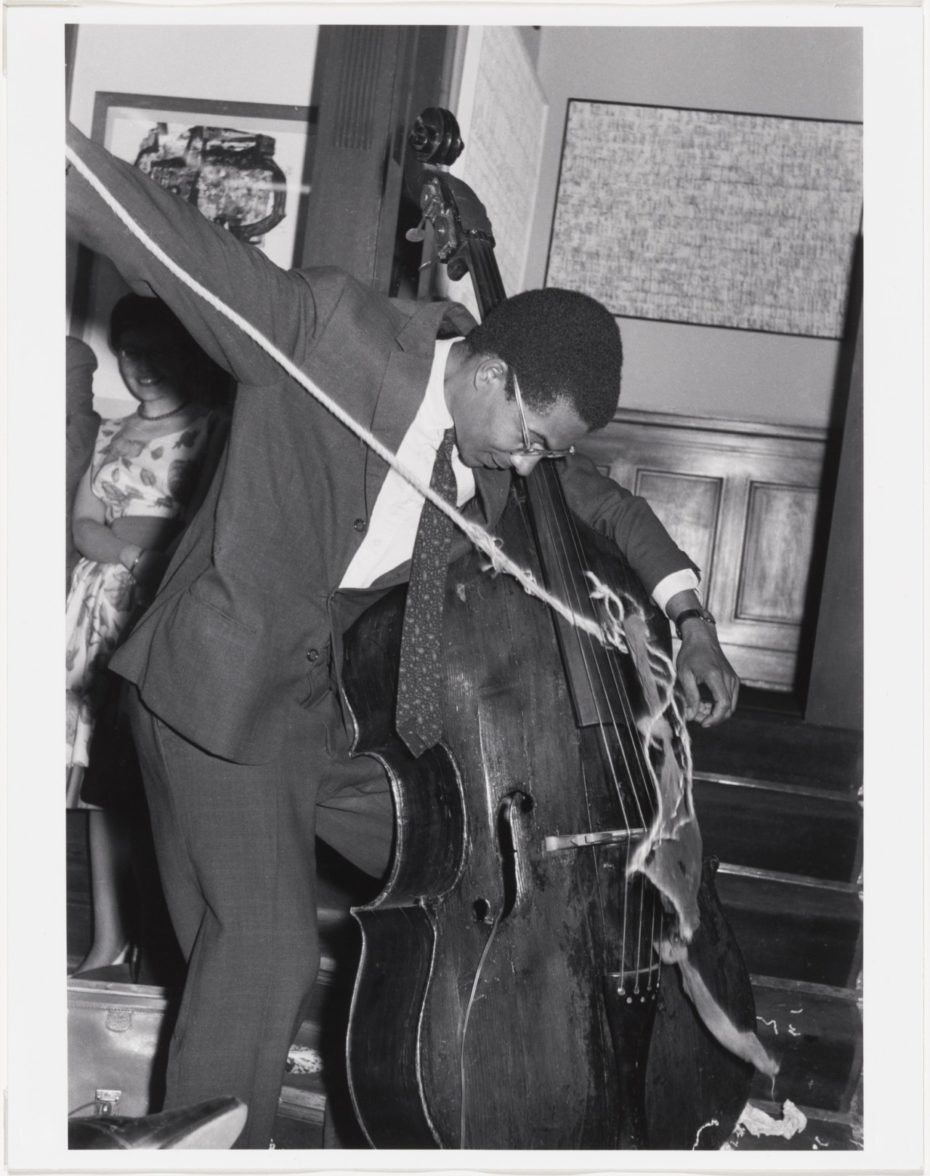

When an artist named George Maciunas looked up the word “flux” in the dictionary in 1960, he found seventeen definitions. “Flux” can be used as a verb, an adjective, or a noun. The multiplicity of the word made it the perfect term for the art movement he was in the process of creating; a loose collection of artists, writers, scholars, and performers whose interdisciplinary work was on the cutting edge of the sixties avant garde. Fluxus encapsulated the question eternally proposed by the avant-garde: “what is art?” Can silence be music? Can a wedding or a funeral be a piece of performance art? Can art really be made by anyone? The most recent evocation of this question has come with the rise of NFTs (non-fungible tokens) within the crypto industry. Digital assets are fast gaining momentum in the art world and became one of the biggest buzzwords of 2021. And while the concept of NFTs may still be a black box to many, it’s not entirely novel. Much like the radical art of Fluxus, crypto art is difficult to “collect” or own in the traditional sense, and both concepts essentially remove art from mainstream museums and white gallery walls. Long before the internet and crypto mania, Fluxus worked to overturn cultural conventions and hegemonies and with George Maciunas at the helm, the movement revolutionarily declared that art was for everyone and art could be anything.

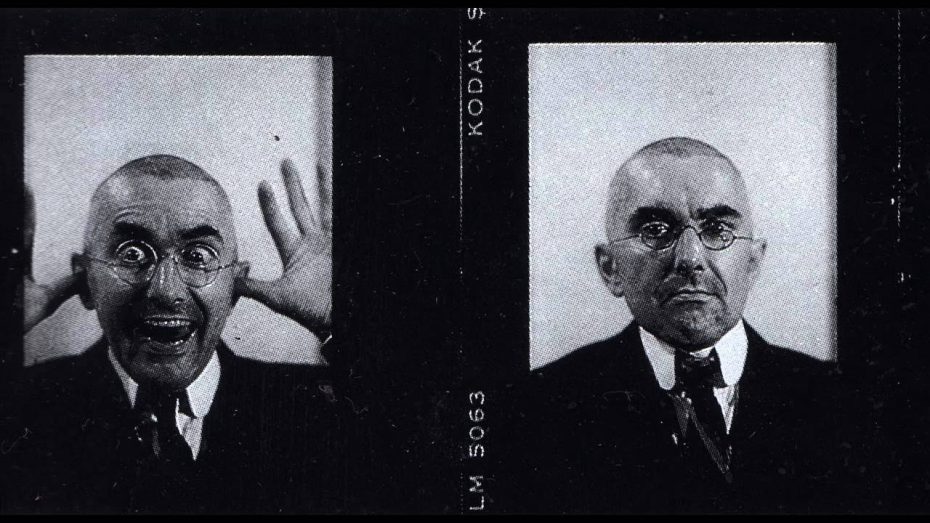

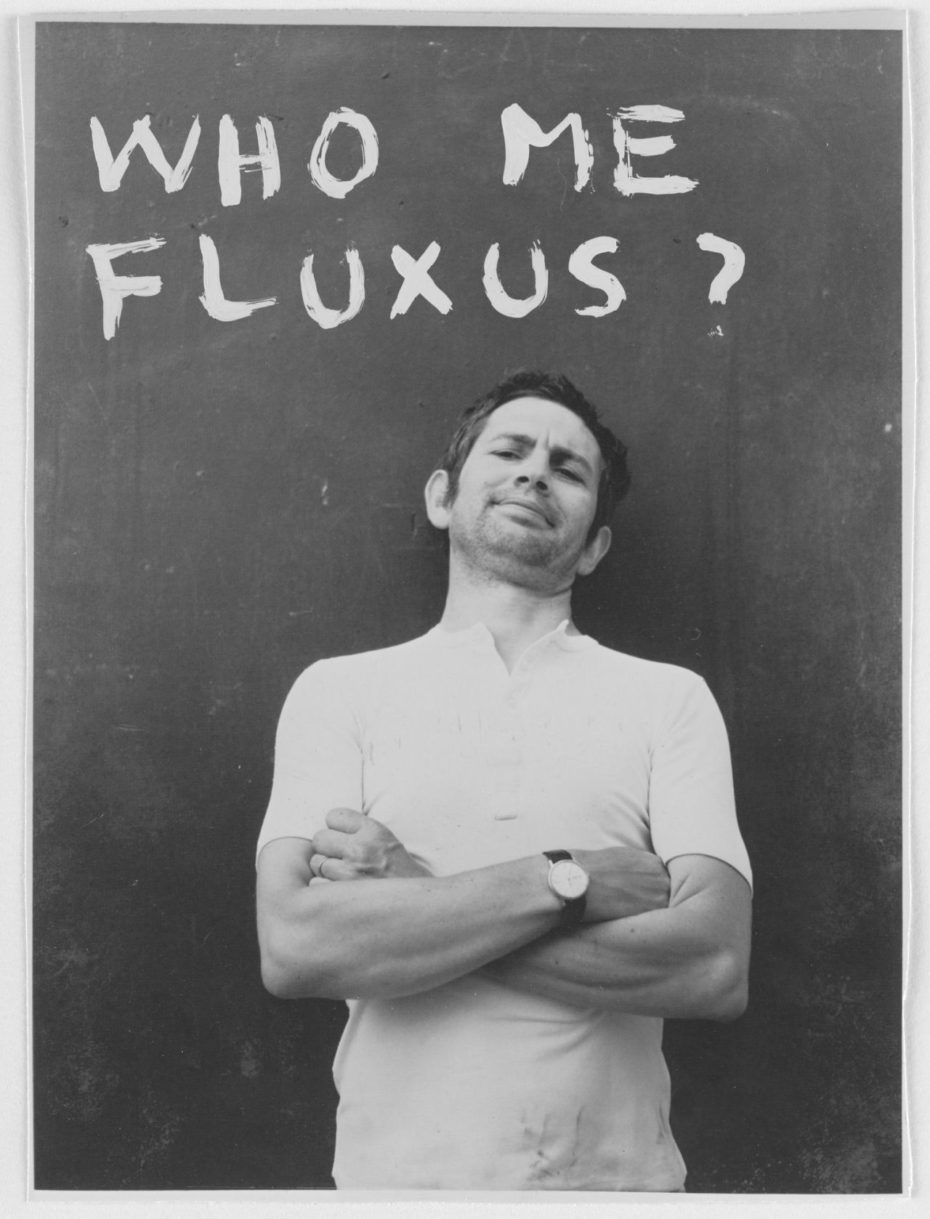

George Maciunas was a Lithuanian-American artist and architect who trained at Cooper Union, the Carnegie Institute, and NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts before working for several architectural firms during the 1950s. He first used the term Flux as the title for a magazine he was attempting to launch from the Lithuanian Cultural Club of New York. Acting as the editor and publisher himself, Maciunas wanted to create an international, interdisciplinary quarterly that covered every aspect of the avant-garde, from cinema to nihilism, from events to sound poetry. Maciunas co-founded the AG gallery in 1961 in New York and began to hold events there, working with a circle of artists that included Yoko Ono, a core member of the movement.

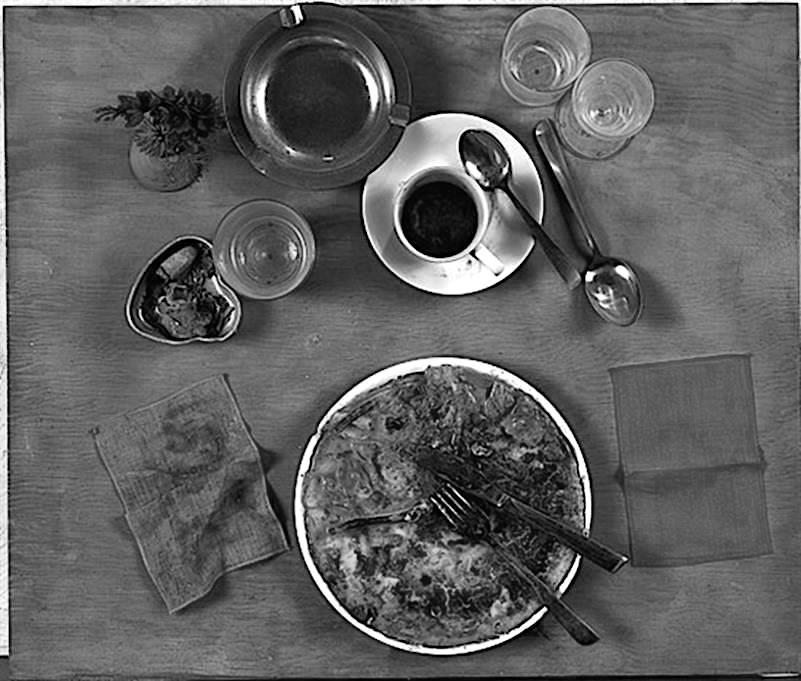

In June 1971, the Fluxus artist George Maciunas threw a dim sum party in New York for guests including Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono and John Lennon, who became an honorary Fluxus artist, not just by virtue of his relationship with Yoko but for his Dadaist humor in own his lyrics, other writings, and drawings. The digital video footage of that surreal party, come to think of it, would make a great candidate for an NFT.

“Fluxus artists pushed art well outside of mainstream venues,” one writer notes in a piece for Artsy.net. “Their informal, spontaneous, and often ephemeral pieces were not only difficult to collect and codify; they were also sometimes hard to recognise as art. But museums and galleries eventually caught up and absorbed their work. So too did younger generations of artists, who continue to build on the freedom that the movement introduced into artmaking with their own work.”

A major early event for Fluxus was the 1962 Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik, or Fluxus International Festival of Newest Music. The festival consisted of 14 concerts that spanned several weekends. The choice to hold the festival in Germany was partially due to the popularity of New Music there, as well as the many Americans living in Germany at the time, most of them employed by the United States military. This included Maciunas, who had arrived in Wiesbaden in 1961 in an attempt to flee from debt collectors.

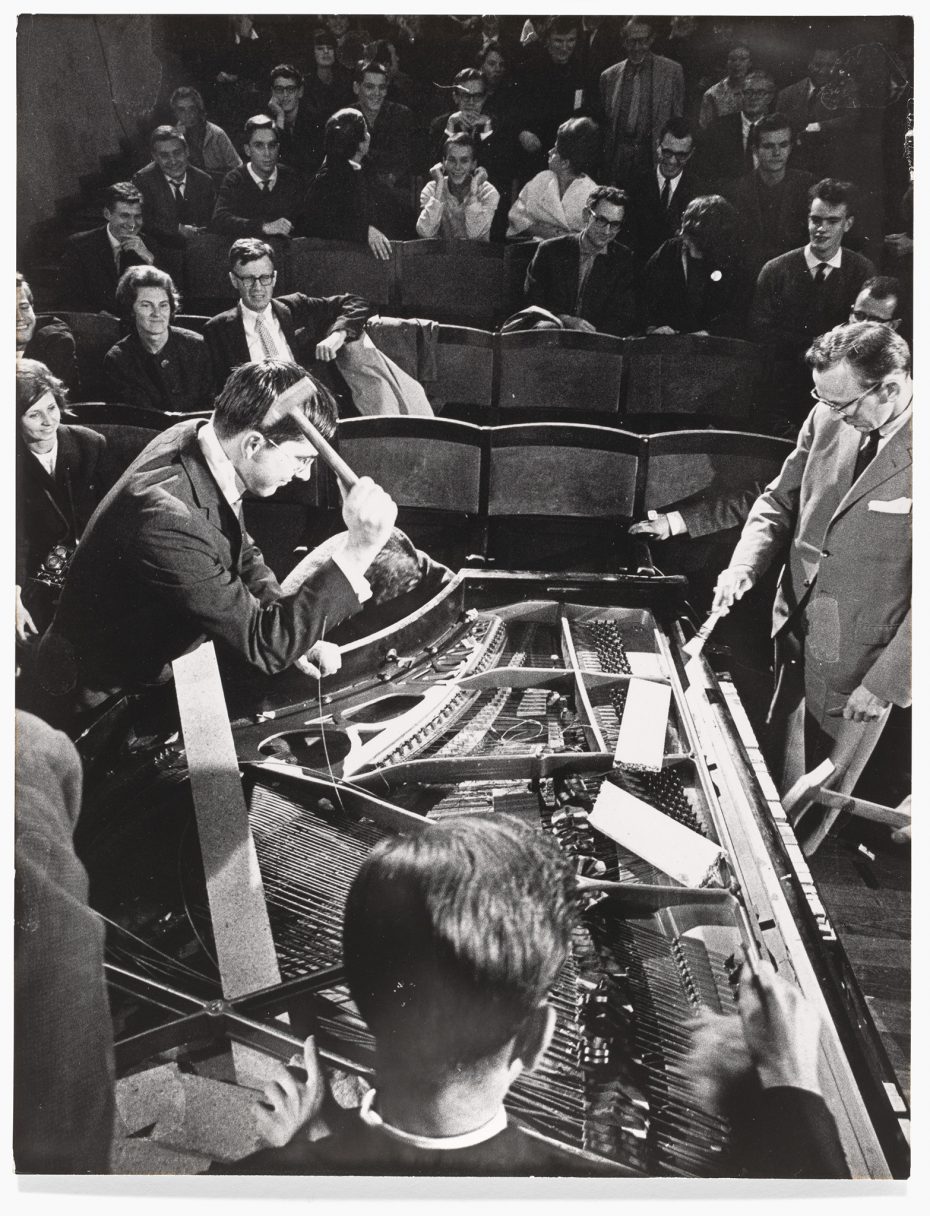

The most famous performance of the festival was Piano Activities, a composition by Philip Corner. Conceptually, the piece explores the sounds that can be made with a piano without touching the keys. Maciunas and several other artists scratched, struck, and eventually destroyed the piano. The work shocked the German public, ultimately raising the international profile of Fluxus and its members.

John Cage is often cited as an important influence on the Fluxus sensibility; Maciunas took great interest in the work of the experimental composer best known for his work 4’33”, which was performed in the absence of deliberate sound. Another inspiration was Marcel Duchamp and the Dada movement.

Maciunas would sometimes refer to Fluxus as Neo-Dadaism, a revival of the movement that thrived in Europe during the 1910s and 20s. Both Cage and the Dadaists shared similar sensibilities with Fluxus, chief among them, the rejection of traditional perceptions and presentations of art, exemplified through Cage’s silence filled symphonies and Duchamp’s “anti-art” ready-mades such as his famous “Fountain” and “Bicycle Wheel”.

Yet the origins of Fluxus were far different from those of Dada. In an interview, Fluxus artist Dick Higgins describes how, although their aesthetic and political sensibilities overlap, Dada began with an idea, followed by the work, while Fluxus emerged out of a group of artists already creating the work. Fluxus is more complicated to pin down and define than other artistic movements. In fact, “Fluxus network” seems a far better term for the style than “Fluxus movement”, for although artworks by Fluxus artists sometimes share a physical aesthetic, what was most important to the artists was the process in which they were made. Indeed, a cornerstone of Fluxus art is the concept that the process is prioritized over the product.

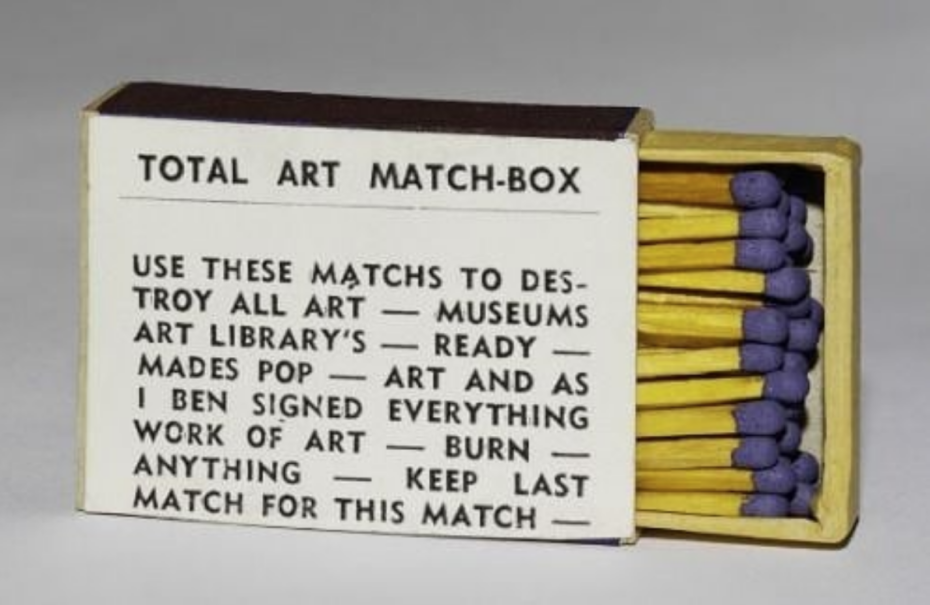

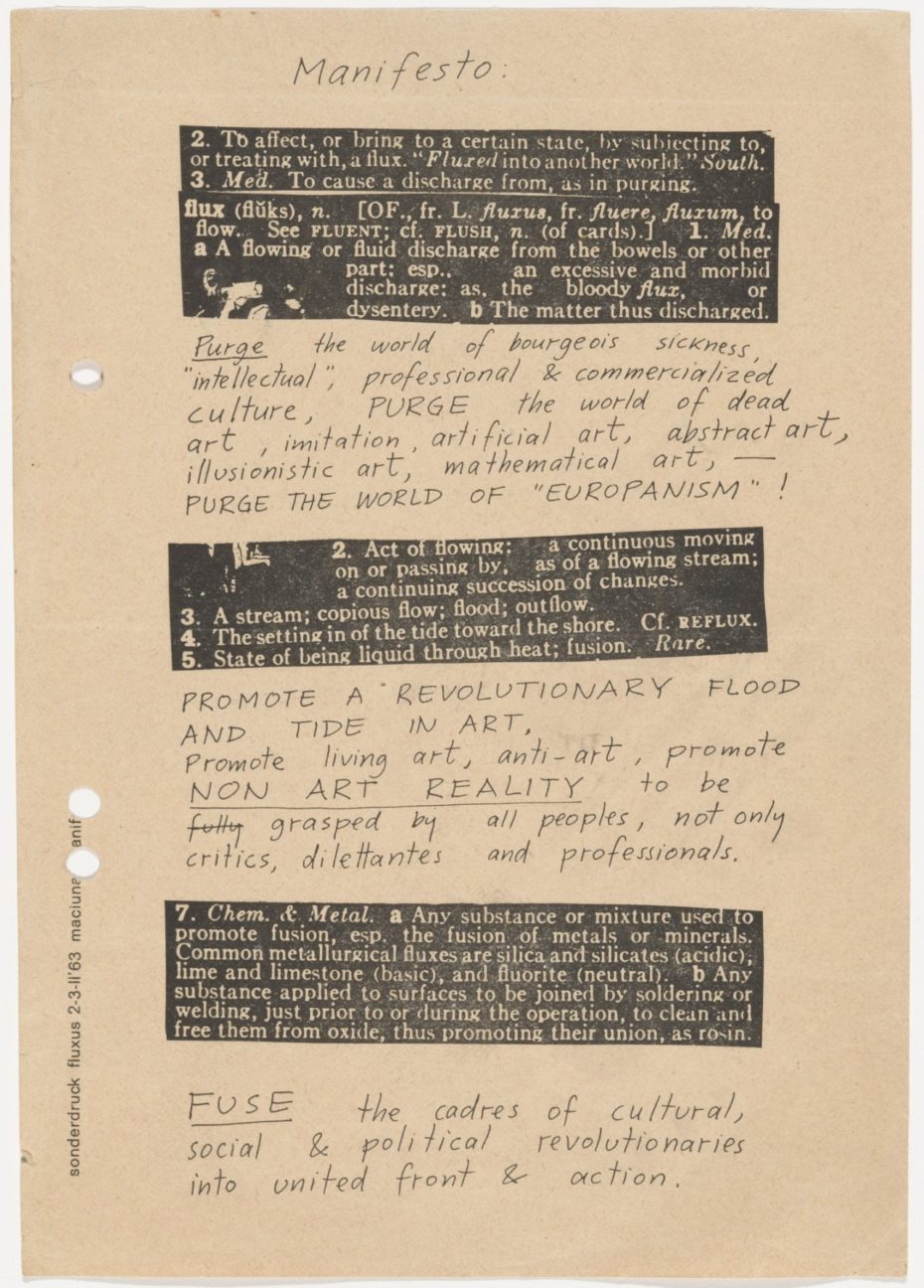

In 1963 Maciunas published the Fluxus Manifesto, clarifying that the objectives of the artistic movement were to “promote a revolutionary flood and tide in art, promote living art, anti-art, promote non-art reality”. In a nutshell, this was art intended to eradicate a high brow view of art that so often alienates the ordinary person. It was the idea of making art from everyday experiences and what it meant to be human; putting on events and performances in the streets and getting the public involved.

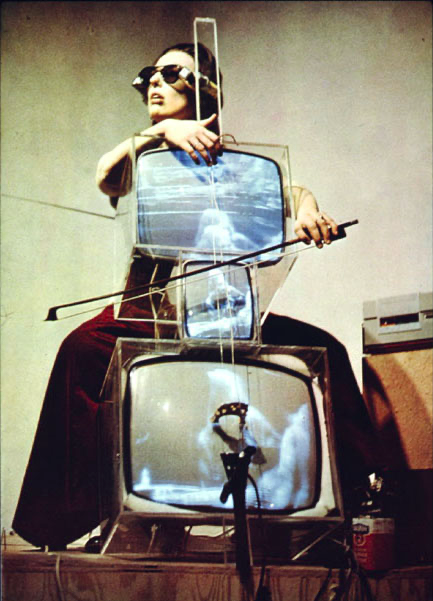

Within the Fluxus circuit, events were known officially as “Happenings”. Behind many of these Happenings in New York, Paris, Berlin and beyond, was Germany’s most dedicated Fluxus artist, Wolf Vostell, who was also the first artist in art history to integrate a television set into a work of art. He also took his art to the streets, testing the public with his radical Fluxus ideas. Here is his 1968 Happening on the H-Bahn, a suspended, driverless passenger suspension railway:

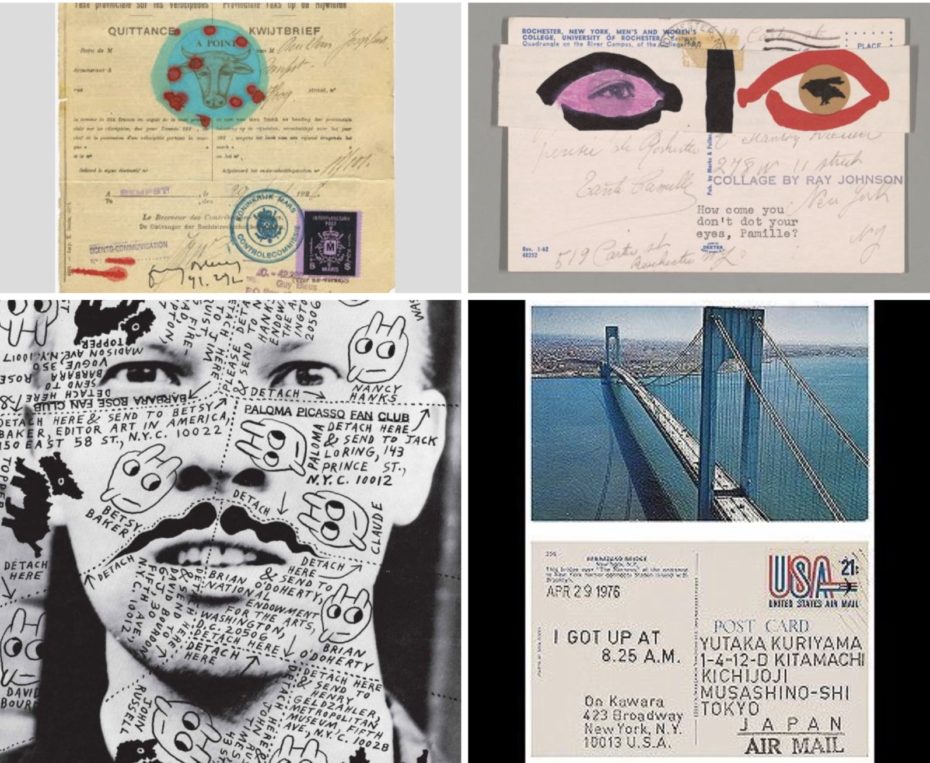

Along with video art, conceptual art and intermedia art (inter-disciplinary art activities), mail art also developed out of the Fluxus movements of the 1960s. The artistic movement centered on small-scale works, postcards inscribed with poems or drawings, and sending them through the postal service rather than exhibiting or selling them through conventional commercial channels. The mail was considered art once it was dispatched. Fluxus artists had also been involved since the early 1960s in the creation of artist’s postage stamps, spawning a vibrant sub-network of artists dedicated to creating and exchanging their own stamps and stamp sheets. Artist Jerry Dreva of the conceptual art group Les Petits Bonbons created a set of stamps and sent them to David Bowie who then used them as the inspiration for the cover of the single “Ashes to Ashes” released in 1980.

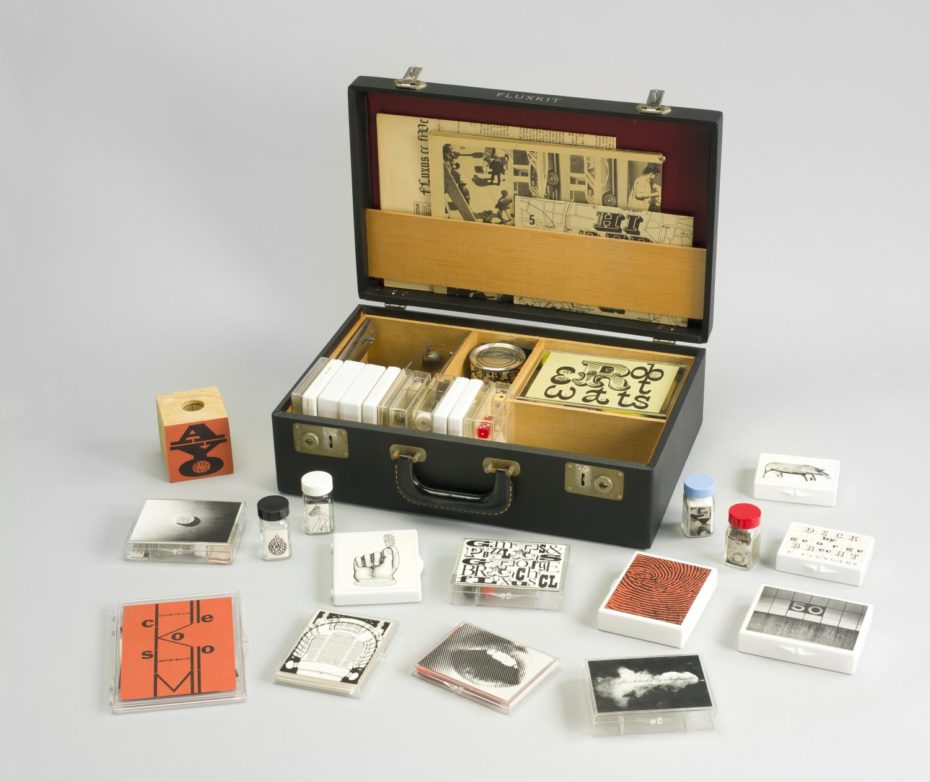

Around the same time as the new music festival, Maciunas began producing a series of game-like kits called Fluxboxes or Fluxkits, in unlimited edition that were small assemblies of objects meant to create Fluxus art with, for example, a briefcase containing a noisemaker, a Fluxus newspaper, a film, a game, or another type of art object. Each element was produced by a different artist. The goal of the Fluxkits was to democratise art and to allow anyone to participate. The Fluxkit rejected any ideas of authenticity or authorship, instead celebrating collaboration, mass production, and accessibility.

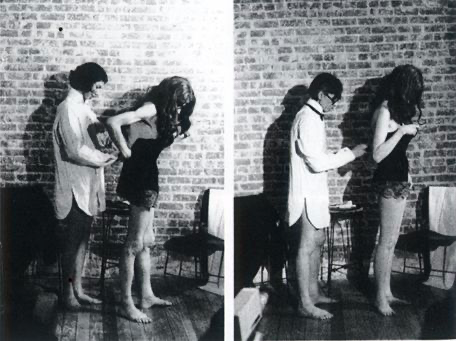

For the fifteen years, before his early death, George took on a plethora of projects in New York, from housing cooperatives to films, anthologies, events, and even a Flux chess set. Though Fluxus doesn’t have a definitive endpoint, the movement was considered to be over after the death of Maciunas in 1978. The events surrounding Maciunas’ funeral are often classified as the last Fluxus events. Called the “Fluxfuneral” and the “Fluxfeast and Wake”, artists performed, mourned, and only ate food that was white, black, or purple. Only months before, when it was clear Maciunas would soon die from pancreatic and liver cancer, he and his collaborators held a “Fluxwedding”. Maciunas married his long time companion, poet Billie Hutching. The bride and groom switched outfits midway through.

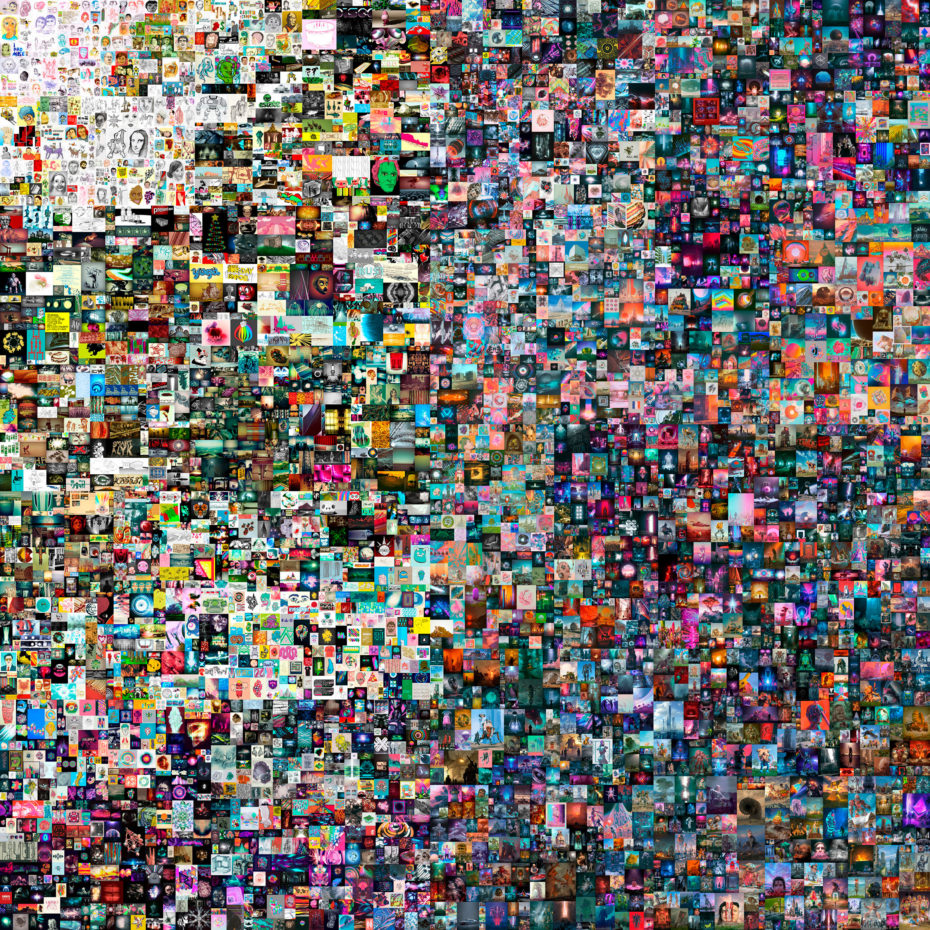

Half a century later, the Fluxus network is still in place, exemplified by contemporary artists who continue to practice Fluxus values. From an art historical standpoint, a line could be drawn from Dada to Fluxus to Andy Warhol’s factory, to street artists like Banksy and ending today with NFT crypto art. Consisting of a digital artwork verified and authenticated by blockchain, NFTs can be anything from a collection of pixels to a JPEG image to a screenshot of a tweet (Twitter founder, Jack Dorsey’s first tweet sold as an NFT for an oddly specific $2,915,835.47). While some critics remain skeptical about the artistic value of works that are entirely virtual and intangible, others, like Jerry Saltz of New York Magazine, have been quick to jump onboard and give NFTs the blue-chip endorsement leading to bidding wars at prestige auction houses. After breaking records in March for their $69 million sale of Beeple’s “Everydays: The First 5000 Days”, Christie’s listed a sale of digital pieces by Andy Warhol, bringing with it a fierce debate about authenticity within the world of digital art. Gucci held an auction ending on June 3rd of an NFT drawn from a video used in their Fall/Winter 2021 show. Sotheby’s joined the trend with a sale in April of NFTs from the artist known as Pak, that sold for over $16 million, quickly followed by the creation of a virtual gallery called Natively Digital: A Curated NFT Sale” which netted a total of $17.1 million.

Artists producing NFTs carry a spirit akin to that of the Fluxus artists, seeing themselves as figures on the cutting edge of both technology and art, challenging what art can be. Seen in the work of Beeple a.k.a Mike Winkelmann (the most financially successful and well known NFT artist so far), crypto art often shares an absurdist, irreverent tone that calls to mind Fluxus pieces like Piano Activities. Both movements reject art history by valuing process over finished product. Both criticise their respective political environments through satirical imagery and symbolism (see Beeple’s “sweet god I hope this picture stands the test of time“). Of course, Fluxus never had the market NFTs have – crypto art is intrinsically linked to buyers with millions in cryptocurrency and few places to spend it – yet the sensibilities remain the same. In an interview, NFT artist Beeple is asked about his artistic inspirations and replies “I’m going to be honest, when you say, ‘Abstract Expressionism,’ literally, I have no idea what the hell that is.” It’s hard to not hear the echos of George Maciunas, who, when asked to define Fluxus, was known to play recordings of dogs barking or geese honking.

https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/c12908/

Nagasaki Sites Associated with Endō Shūsaku’s “Silence”

In February 1582, four Japanese youths left Nagasaki bound for Europe as part of the Tenshō embassy. The diplomatic mission, among the first recorded accounts of Japanese in Europe, was initiated by Alessandro Valignano, an Italian Jesuit priest who accompanied the young emissaries Itō Mancio, Chijiwa Miguel, Hara Martinho, and Nakaura Julião—all aged just 13 or 14—on their journey half-way around the globe.

Studying at a Jesuit seminary in Arima on the Shimabara Peninsula (today part of Nagasaki Prefecture), the young men had been instructed in subjects ranging from Latin to astronomy to Western music. In Europe, the young Christians travelled to Portugal, Spain, and Italy, where they met with leading cultural figures and rulers and had an audience with two Popes. Below is a brief introduction of the four Tenshō envoys.

Born in 1569 in Hyūga province (Miyazaki Prefecture), he was the grandson of daimyō Itō Yoshisuke. He was eight years old when Yoshisuke was defeated by the Shimazu clan and sought refuge with the Christian daimyō Ōtomo Sōrin of Bungo province (Ōita Prefecture), who would later help sponsor the Tenshō mission.

Born in 1569 in Hizen province (Nagasaki Prefecture). He was four years old when his military commander father Chijiwa Naokazu was defeated by the Ryūzōji clan, forcing he and his mother to take refuge with his uncle, the Christian daimyō Ōmura Sumitada. He was one of the first students at the Jesuit seminary in Arima.

The only known documents of his birth come from Italy, which indicate he was born around 1569 in Hasami in Hizen province to Hara Nakatsukasa, a prominent figure in the Ōmura domain. He is considered to have been the brightest of the four ambassadors.

Records kept by Jesuits in Rome indicate he was born in 1568 in Hizen province to Kozasa Sumiyoshi, the lord of Nakaura Castle. After his father was killed in battle, he came under the patronage of Ōmura Sumitada’s son Koshō.

A newspaper printed in the Bavarian city of Augsburg in 1586 depicts the members of the Tenshō embassy. Clockwise from top left: Nakaura Julião, Father Diogo de Mesquita, Itō Mancio, Chijiwa Miguel, and Hara Martinho. (Courtesy Kyoto University)

Sailing eastward, the embassy grappled with rough seas, unfavorable winds, and outbreaks of disease that required it to stop, sometimes for months on ends, in different ports as it slowly made its way to Europe. It touched at Macau, Malacca, and Goa before rounding the Cape of Good Hope, finally reaching Lisbon on August 10, 1584, some two and a half years after leaving Nagasaki.

A digital exhibit at the Ōmura City History Museum retraces the route taken by the Tenshō embassy on its journey to Europe. (© TeamLab)

The Tenshō embassy officially represented Ōtomo, Ōmura, and Arima Harunobu, the three most important Christian daimyō, and carried letters from them to the pope. However, the impetus for the mission was wholly Valignano’s, who conceived of it with two main objectives in mind.

First, he wanted to introduce Japan to Europeans, reasoning that the sight of the young Japanese would help win the support and financial backing of the pope and the king of Spain and Portugal for further Jesuit missionary work in East Asia. Second, he wanted to impress on the emissaries the grandeur and authority of the Christian religion in Europe in expectation that they would report this when they returned home, raising the stature of Christianity in Japan and helping in its spread.

There was the risk that Europeans, who knew almost nothing about far-away Japan, would look down their noses at the foreigners, and Valignano went to great pains to groom the Japanese youths to conduct themselves in a “cultured” fashion. Certainly, there were some who treated the four as exotic oddities, but most accounts describe the ambassadors as fulfilling their diplomatic duties with aplomb.

From Lisbon, the embassy made its way to Spain, stopping at cities along the way before reaching Madrid, where it was met warmly by Philip II. The king of Spain and Portugal, Philip ruled over a vast, global empire that made him the most powerful ruler in Europe next to the pope in Rome. He was impressed by the resolve and intelligence of the boys and sent letters to the mayors and administrators of the cities along their route ordering that the envoys be welcomed and provided with any funds and support they required.

The embassy triumphantly made its way to Rome, where Pope Gregory XIII received it at Saint Peter’s Basilica with all the ceremony fitting an official mission. Pope Gregory died shortly after, but his successor Sixtus V was equally welcoming of the mission, inviting the four envoys to take part in the procession to the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran following his selection. A fresco in the Sistine Hall of the Vatican Library captures the scene and shows the young Japanese emissaries astride white horses.

From left: Saint Peter’s Basilica, where the embassy had its audience with Pope Gregory XIII. (© Reuters); the delegation also visited Venice, with records describing the waters next to the city’s Piazza San Marco filled with boats in welcome of the Japanese emissaries. (© Amano Hisaki)

Having succeeded in its mission after more than a year and a half in Europe, the Tenshō embassy began the long journey home in April 1586. However, the situation awaiting them in Japan had changed dramatically. Landing in Macau in August 1588 the mission learned that warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi had issued an edict the previous year expelling Christian missionaries from Japan. Concerned, the members of the embassy pushed on, reaching Nagasaki in July 1590 after eight and a half years away.

Some time later, the four emissaries and Valignano were summoned by Hideyoshi to his Jurakudai Palace in Kyoto to give an account of their journey. Portuguese Jesuit missionary Luís Fróis describes in his book History of Japan how among the tributes offered to the warlord, Hideyoshi prized the gift of Arabian horses, with a demonstration of Western equestrian techniques by the Portuguese handlers of the animals making a deep impression.

There was no shifting the growing anti-Christian tide, though. Hideyoshi and his successor Tokugawa Ieyasu issued a string of edicts against the religion, and persecution of missionaries and followers of the faith increased. Droves of believers in strongholds like Nagasaki, Ōmura, and Shimabara were forced to recant or died for their faith.

Of the four Tenshō emissaries, Itō Mancio, Hara Martinho, and Nakaura Julião were ordained Jesuit priests in Japan. Itō, the leader of the delegation to Europe, carried out missionary work in Kyūshū and the Chūgoku region in western Honshū until his death from disease in 1612. Hara, who was a linguistic prodigy, fled to Macao as persecution intensified, teaching and translating there until his death in 1629. Nakaura remained in Japan and continued his missionary activities even as persecution of Christians intensified, dying a martyr in 1633.

The ruins of Saint Paul’s Cathedral in Macao. Hara Martinho is said to be buried at the altar of a church in the historic district of the city, which is a World Heritage site. (© Pixta)

The remaining member of the mission, Chijiwa Miguel, entered the Jesuit order like his colleagues, but left sometime between 1601 and 1603. He eventually abandoned the Christian religion, and history remembers him as an apostate.

What little is known about Chijiwa’s life after returning to Japan provides no clues as to why he turned from Christianity. After leaving the Jesuits, he took Seizaemon as his given name and served Ōmura Sumitada’s successor Yoshiaki before fleeing the domain after the daimyō banned Christianity in 1606. He spent time in Arima and Nagasaki, married, and fathered four children, but it was not known when and where he died.

Then in 2003, researcher Miyazaki Eiichi came across a grave in Ikiriki, a village in Isahaya in central Nagasaki Prefecture, purported to belong to Chijiwa Miguel’s fourth son Genba. He reached out to fellow researcher Ōishi Kazuhisa, a local high school teacher and expert on stonework, and encouraged him to have a look.

Miyazaki had been digging through Ōmura domain records piecing together the Chijiwa line—he had uncovered that Ōishi was distantly related to Genba on his mother’s side—and sharing his findings in the newsletter of the local historical society. Despite the genealogical connection, Ōishi showed little interest in visiting the site at first as experience told him that grave markers from the Edo period (1603–1868) generally were of a design mandated by the shogunal government and offered few historical clues.

Ōishi finally visited the grave with Miyazaki three months later. Speaking with Ide Norimitsu, a local who had long tended the grave, he learned that the site had been revered for generations as Genba’s resting place. However, all that Ōishi found on the face of the marker were two posthumous Buddhist names and a date corresponding to 1633.

Suspecting that the story of it being Genba’s grave was a local legend, he inspected the reverse side of the gravestone and found something that seemingly proved the claim. There carved in the stone was the name Chijiwa Genba.

But Ōishi knew better. It was customary with old gravestones for the name of the chief mourner to be carved at the back, indicating that Genba was the sponsor of the tomb, not the inhabitant. The early date also made it unlikely that Genba was buried there. Of equal interest was the fact that the grave contained a couple. The two individuals interred were likely family members, raising the probability that it was Chijiwa Miguel and his wife, an exciting proposition.

Ide added credence to the theory, saying that family lore held that the occupant of the grave had a grudge against the Ōmura domain and had been buried where he could “keep an eye on things.” If true, this further reduced the odds of it being Genba, who records show was adopted into the Ōmura clan and lived within the confines of nearby Kushima Castle.

From left: The grave sets on a hill in Ikiriki overlooking Ōmura Bay; the name Chijiwa Genba no jō engraved at the back of the gravestone. (© Amano Hisaki)

Ōishi Kazuhisa (left) and caretaker Ide Norimitsu. (© Amano Hisaki)

The only way to be certain that the grave belonged to Chijiwa Miguel was to carry out more research, including scouring Ōmura domain records to determine what if any connection Genba had to the Ikiriki site. Ōishi was able to make a link through an important Ōmura vassal, giving him the certainty he needed to announce the discovery to the press, which he did in 2004. He was careful to avoid reaching any definitive conclusions, though—that would require carrying out an excavation.

There have been four separate digs at the site, and the latest in 2021 unearthed the skeletal remains of a man and woman along with a slew of artifacts. Among the items of interest are burial goods such as beads and pieces of glass that are associated with Christian graves. Combined with other research, the findings make a strong case that the site is the final resting place of Chijiwa Miguel.

The discovery of a grave of one of the Tenshō emissaries would be of incredible historical importance. But the strong evidence that Chijiwa received a Christian burial is of immense significance as it rewrites history by overturning the label of apostate and proving that he had in fact retained his faith to the very end of his life.

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: A monument to the four young members of the Tenshō embassy at Morizono Park in Ōmura commemorating the 400th anniversary of the diplomatic mission. © Amano Hisaki.)

Chief editor in the Nippon.com Japanese editorial department. Born in Akita in 1961. After graduating from Waseda University, attended the University for Foreigners of Perugia, earning a degree in Italian language and culture. Has covered sports and other fields for the Mainichi Shimbun for around 20 years. Works include Hamamatsu ōtobai monogatari (The Hamamatsu Motorcycle Story) and a Japanese translation of an Italian biography of Ayrton Senna.