Why Renaissance Paintings Aren’t as Green as They Used to Be

Once a brilliant hue, the pigment verdigris is now mostly brown.

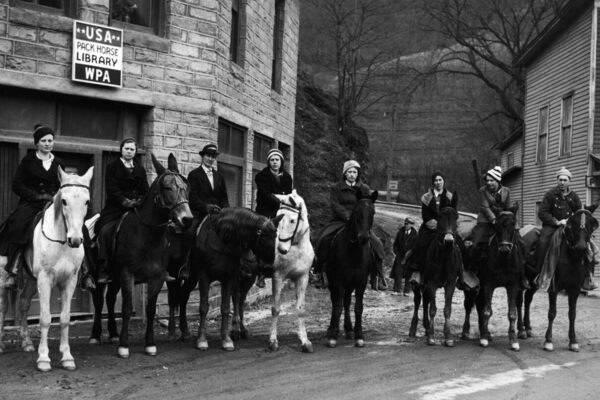

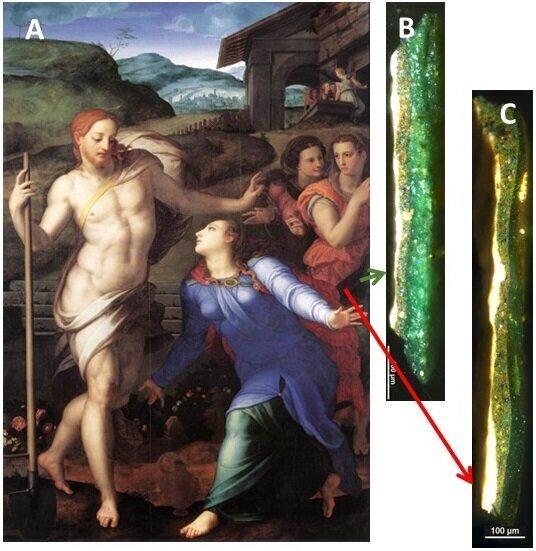

THE ITALIAN LATE-RENAISSANCE PAINTER ANGELO Bronzino spent two years on his 1591 painting “Noli me tangere,” which depicts* Christ as a gardener. The oil-on-wood painting, which was commissioned by a man who wanted to adorn his father’s funeral chapel, would make any dead father proud, depicting a beefy Christ and Mary Magdalene dressed in vivid blues and greens. But if Bronzino saw the painting now, he would probably be sorely disappointed. Over the past four centuries, the once-brilliant green paint has faded into a mucky, unrecognizable brown.

“Noli me tangere,” which hangs today in a gallery of the Louvre, is one of many Renaissance paintings that features a copper-based pigment called verdigris. When fresh, its shade of bluish green is rare and luminous. But like many pigments popular in the 15th through 17th centuries, verdigris is toxic and unstable, Arthur DiFuria, an art historian at the Savannah College of Art and Design, explained in an interview with Copper.org, the website of a trade group that represents the copper industry. By the 19th century, verdigris had fallen out of fashion—mostly due to its poisonous nature—but no one ever figured out why the brilliant green pigment darkened so severely. Now, researchers in France have sleuthed the chemistry behind verdigris’s shadowy tendencies in a study in Inorganic Chemistry.

To anyone living in the 21st century, it might not be obvious that Renaissance paintings were once much more colorful than they look now. “If you look at the paintings of, say, Leonardo da Vinci, they are very, very dark,” says Didier Gourier, a chemist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research and an author of the study. “But they didn’t always look this way.”

Gourier knew that past researchers had speculated that light exposure and oxygen may have contributed to the darkening process, and he decided to analyze the chemical changes that took place in the verdigris. Though they had a plethora of paintings to choose from, the researchers selected two Renaissance paintings from the Louvre: Bronzino’s “Noli me tangere” and Jean Fouquet’s “Pietà.” Both works used plenty of verdigris that had sallowed over the years. Gourier took several samples, each smaller than a millimeter, and ran them through an electron microscope.

Presented with incredibly high-resolution images of the paint chips, they contrasted the color changes in verdigris sampled from the center of Bronzino’s painting against verdigris sampled right next to the frame, a shaded area that would have offered protection from light. Their suspicions were proven right when they found the frame-protected paint was far less deteriorated. When Gourier magnified a cracked paint sample from “Pietà,” he found that each crack had darkened, likely due to the diffusion of oxygen in the cracks. “The darkening is not systematic,” Gourier says. This inconsistency helps researchers pick out now-brown verdigris from originally brown paint, he says.

To chemically confirm their theories, the researchers decided to recreate verdigris according to a medieval formula and see how they darkened over an accelerated time scale. “We had to speed up the darkening, because a painting in the Renaissance period would have taken several hundreds of years to darken,” Gourier says. “We calculated that 16 hours of LED illumination corresponds with several hundreds of years of illumination by museum light.”

Verdigris, technically known as copper acetate, has a simple recipe. Simply place metallic copper in vinegar and wait three or four weeks for the metal to react with the acid, producing blue-green copper acetate on its surface. (The Statue of Liberty appears blue-green for the same reason.) The researchers mixed the pigment with boiled linseed oil to make paint, as was the custom in the Renaissance. Gourier then placed the recreated verdigris on a thin sheet of glass to allow (simulated) centuries of light to pass through the sample. As if on cue, the gaudy verdigris darkened into muddled brown, just as the researchers expected.

Though Gourier intentionally selected two paintings with poorly-aged verdigris, the pigment can be detected a little more clearly on other famous works of Renaissance art. Chemical analysis is required to know for sure that a particular painting used verdigris (and it goes without saying that a permit to sample a 15th-century masterpiece is not easily acquired), but the charismatic green can be spotted in several works by Sandro Botticelli, such as the resplendently verdant “The Mystical Nativity,” which depicts—you guessed it—Christ and the Virgin Mary. DiFuria also suspects that Jan van Eyck’s green-sheened “Ghent Altarpiece” uses verdigris. The greens in these paintings are presumably less prismatic than they would have been several centuries ago, but they still, somehow, seem to glow.

* Correction: This story previously stated that the painting “Noli me tangere” is also called “Christ the Gardener.” In fact, it depicts Christ as a gardener.