People

Van Gogh, Visionary Artist, Was Once a Truly Terrible Art Dealer. Until This Guy Fired Him

If Van Gogh had been able to keep a steady job, he might not have become a great artist.

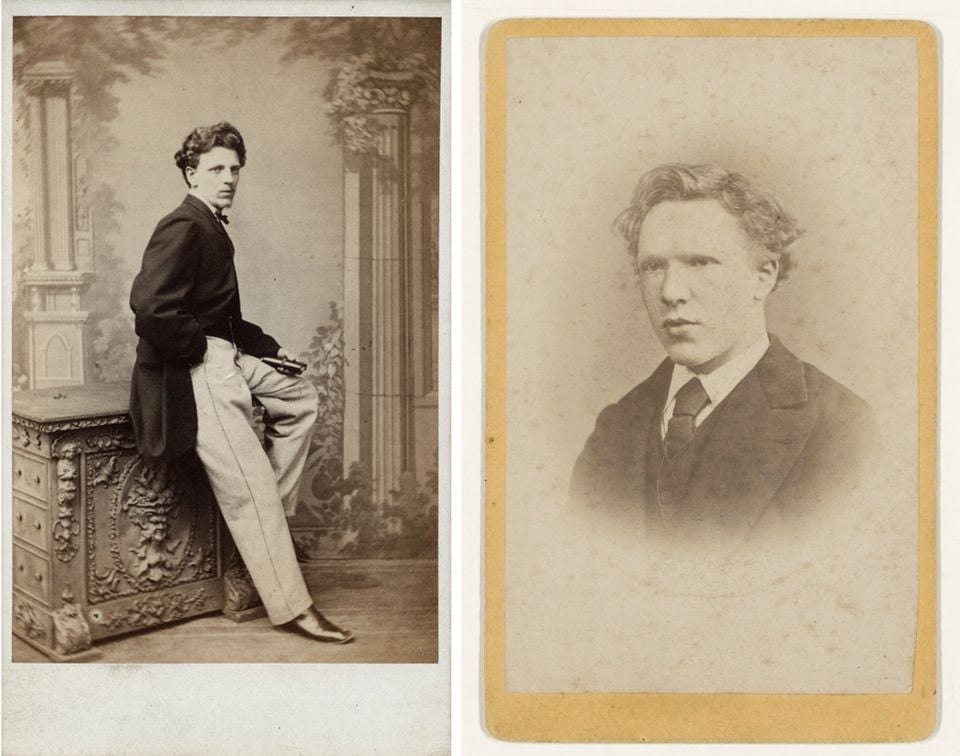

The National Portrait Gallery in London has discovered the first known photograph of Charles Obach, the manager of the Goupil Gallery in London, where Vincent van Gogh worked during a short-lived career as an art dealer. Van Gogh started working at the firm’s branch in The Hague in 1869 but got fired in 1876, after Obach informed the company’s owner that the young Dutchman was underperforming.

At first, the artist seemed to excel at Goupil. He was excited when his brother Theo also got a job at the company, congratulating him in a letter saying “it’s such a fine firm, the longer one is part of it the more enthusiastic one becomes.” But that was when the artist was still working at The Hague, making a respectable 50 Guilders a month helping pack paintings, etchings, and photographs. When he went to work for Obach in the company’s London warehouse, he complained to Theo that “the firm isn’t as exciting as The Hague branch.”

Before long, things had taken a turn for the worse. “Unfortunately Van Gogh turned out to be an awkward employee, lacking tact, and he was poor at dealing with customers,” wrote Van Gogh expert Martin Bailey for the Art Newspaper, announcing the discovery of Obach’s photograph. Van Gogh did a couple of stints at Goupil’s Paris office, in the hopes that location would be a better fit, but things didn’t work out. Based on Obach’s damning evaluation, Van Gogh was fired in January 1876, while working in Paris.

The loss of his gallery job was a pretty crushing financial blow to Van Gogh—living in poverty, he was forced to rely on Theo, who kept working as an art dealer, to make ends meet for the last 10 years of his life. But had Van Gogh not been fired, who can say whether he would have ever pursued a career as an artist.

Vincent Van Gogh, The Potato Eaters (1885). Courtesy of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Of course, it took a few more years for Van Gogh to find his true calling—before taking up a paintbrush, he taught in an English boarding school, worked briefly at a bookshop, and became a missionary, failing his entrance exam to study theology at the University of Amsterdam. Finally, in 1880, he moved to Brussels. There, Van Gogh studied with Dutch artist Willem Roelofs and attended the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, setting himself on the path to artistic greatness.

The portrait of Obach was taken in a photography studio in the 1870s. There are no known photographs of Van Gogh as an adult, just a single portrait of him as an adolescent, taken in 1870 when the artist was 19. (The notoriously camera-shy painter may have been captured in a group photograph or twoover the years, but that’s never been proven.)

“I myself still find photographs frightful and don’t like to have any, especially not of people whom I know and love,” Van Gogh wrote in a letter to Theo, asserting his preference for painting since photographs “are faded more quickly than we ourselves, while the painted portrait remains for many generations.”

As for Ogden, he went on to open his own art gallery in London. Van Gogh saw him one final time, in The Hague in 1881. Went the artist died, his former boss wrote Theo a letter offering his “heartfelt condolences on this distressing occasion.”

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE