I’m a novelist and my husband Sabin Howard is a classical figurative sculptor. Currently he’s the sculptor for the National World War I Memorial, which will be a 56 foot long bronze relief set in Pershing Park, Washington D.C.

Before Sabin forayed into public art, he sculpted from life models. Over the course of designing soldiers in combat and nurses tending the wounded for the WWI Memorial, he has evolved into an expressive humanist. But for decades he put clay over a steel armature while looking at a flesh-and-bones body in space, hiring models the way Canova or Rodin did. The model in Sabin’s studio was a vehicle both for an individual figure with psychological expression, and for an allegorical one that embodies a higher ideal.

Sabin has always been of the view that art elevates us. His body of work includes heroic scale sculptures, including the Aphrodite. Eight women posed for her: a flamenco dancer for the legs, a yoga teacher for the core. I can relate funny anecdotes about the responses from Craig’s List to his ad for a boob model. Sabin worked on Aphrodite for about a year. His work is slow art. Clay is painstakingly accreted to the high points of muscles spiraling over bone. One day he phoned from his studio. He said, “I have a chainsaw. Her gesture is wrong. I’m cutting off her left arm.”

It was months of work. Amputated.

When I tell this story, people smile and nod. This is the tale of an artist with an uncompromising vision of his art. It’s an archetype. They understand. But there’s another implication that they tend to miss. That is, Sabin had paid a dancer to stand and bear her arms aloft while he sculpted. When Sabin lopped off the goddess’s arm, we took a financial hit.

Art isn’t free to produce. Especially the kind of art Sabin makes. He buys steel and foam to make an armature; he lays out cash for clay and sculpting tools; he employs models, a photographer for reference images, a mold-maker, a foundry to pour bronze, and a finisher to weld the cast pieces together. He writes a check every month for his studio.

This is a business. A business driven by passion, but a business nevertheless. For nearly two decades, I’ve helped my husband run it. He moved away from the gallery system because galleries take a hefty 50 percent commission. My various literary agents take 15 percent for U.S. sales and 20 percent for international, so half the price for a sculpture strikes me as gouging the artist.

Few artists complain about the percentage; most spend so much time and energy learning their craft that they pay little attention to the business of art. They also cherish the notion that the real value of art isn’t measured in dollars but in its ability to influence culture and move its audience. Of the multitude of artists I’ve met over the years, most seem to want the gallery to hand them an allowance, so that all they have to do is keep making art. They don’t want to roll up their sleeves and climb into the muddy trenches of the marketplace.

But Sabin has an entrepreneurial spirit and he’s good at client cultivation. He decided to forgo the gallery’s percentage and create his own business. As his wife, I’ve been a full partner in all aspects: sales, promotion, marketing, webinar creation and support, web design, writing, and outreach to museums, clients, collectors, and media organizations.

We have better months and worse months. There’s a level of chaos we tolerate because every month sees a different income, and like everyone else, we have fixed costs: our apartment, our health insurance, our daughter’s education. We have to buy tomatoes and lamb chops and shampoo and school uniforms. It can be scary. But, despite the pressure, we’ve come to appreciate the dynamic opportunities afforded by the capitalist model.

That’s why I’m taken aback when someone turns to me and says, “You’re artists. You’re supposed to be left-wing.” By which they mean Socialist. They don’t mean socioeconomically, philosophically, and racially inclusive, or any of the qualities of independent thought and respect for the sovereignty of the individual generally understood as classical liberalism. They mean that we as artists ought to believe in a state-run collectivism that will provide us with an allowance—presumably so we don’t have to exercise our own ingenuity and take responsibility for our financial well-being.

As mentioned, most artists work within the gallery system. The gallery cuts them a check when there’s a sale. Many artists teach, and universities run on a similar model, doling out a pittance with which an associate professor is supposed to make ends meet. It’s a well-greased, time-honored system with a clear hierarchy and a defined path forward. It’s structured. It feels safe.

There’s also a cultural notion that artists are supposed to be too high-minded to make money. The vapid romanticism of the starving artist has been promoted at least since Victorian times. During the Renaissance, a workshop and apprenticeship system, as well as an embedded ideal about the beautification of cities and the ennoblement of public and private spaces, provided a path to livelihood for talented artists. And “starving artist” hearkens to a mistaken idea about filthy lucre—that somehow hard cash and noble ideals are incompatible.

We recently worked with a business partner who was affronted when we explained that our venture together had to culminate in earnings or we couldn’t afford to do it. She felt that what mattered were the ideals behind our platform. Ensconced in her wealth, she couldn’t understand that our ideals are important, but that they will not be realized if we can’t earn a living.

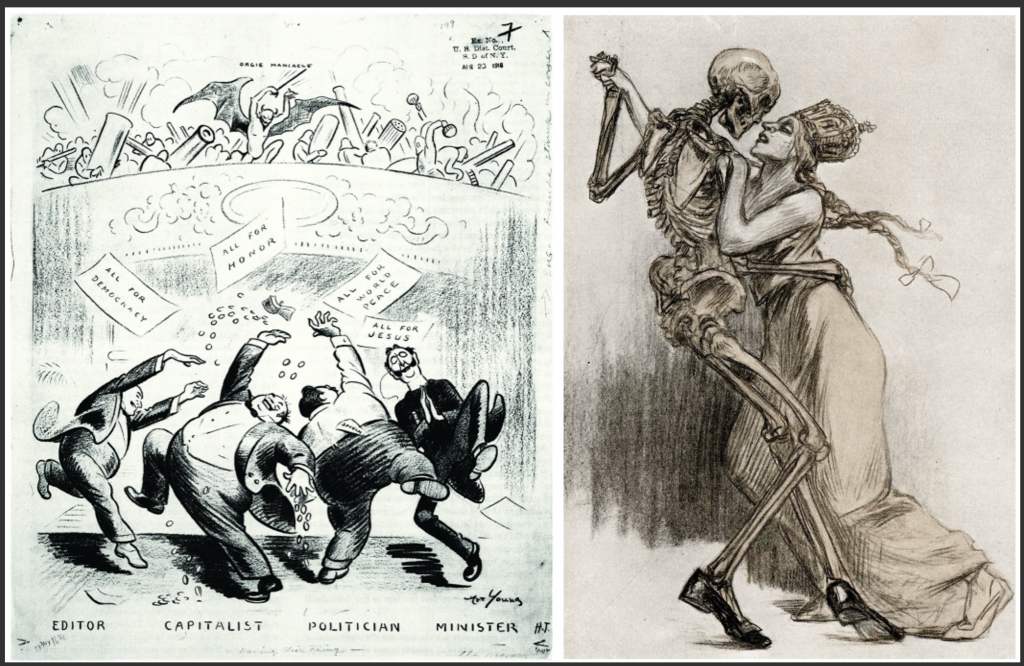

The implications of the left-wing model go deeper than finances. They devolve into a vision of art as a collectivist endeavor: Art by committee. Art by groupthink. The state pays the artist, so the state gets to tell the artist what to make. But the collectivist framework is diametrically opposed to real art.

Real art is the product of the personal, human vision of the artist. However, it is not simply self-expression. Self-expression is worthy and sometimes well-executed, and a small percentage of it is art. Real art, on the other hand, balances the artist’s individual perception with something that is universal in understanding and meaning. People—everyday people without PhDs—feel it in their bones. They may not be able to articulate it but, like pornography, they know it when they see it. And, in fact, there are objective standards for evaluating art. Beauty, excellence, and the artist’s skill matter.

This understanding is incompatible with the fashionably progressive, postmodern credo that only the group matters and, anyway, everything is meaningless. God is dead and so are reason, meaning, and order. All that remains to understand how things are is a sterile process of deduction and, since every person is his or her own Sherlock Holmes, there’s no hierarchy of taste or quality. All is relative. Except that, as always happens, some animals are more equal than others, and the animal that dictates taste is the collective or the state.

The Left behaves in the manner of the totalitarian state they say they fear. They dictate taste and expression. They extinguish an artist’s distinct, personal and human vision if that vision runs contrary to the collectivist agenda. Thus is creative ability squelched. As Ayn Rand declared in The Fountainhead:

…The whole secret of their (the creator’s) power—that it was self-sufficient, self-motivated, self-generated. A first cause, a fount of energy, a life force, a Prime Mover. The creator served nothing and no one. He had lived for himself. And only by living for himself was he able to achieve the things which are the glory of mankind. Such is the nature of achievement.

The inevitable outcome of a collectivist belief system is the ethic and aesthetic of the lowest common denominator. Ayn Rand managed to understand this without God (although, personally, I think she missed the mark on spirituality).

In distinguishing artists from leftists, I respectfully disagree with Jordan Peterson, whom I greatly admire. In a YouTube lecture, he discusses a spectrum with creative artists/non-hierarchical/unstructured liberals on one end and hierarchical/structured/non-artist conservatives on the other end. I believe this spectrum offers too easy a dichotomy. Watching Sabin, and meeting other successful artists, including world-class musicians, painters, and writers, I’ve found that successful creative people have a profound talent for hierarchy and structure. This is just an observation gleaned from personal experience. It’s not the result of a double-blind scientific study.

As the wife of a famous artist, I’ve lived the truth that art transcends social caste and class. Sabin and I have broken bread with billionaires and food stamp recipients, iconic musicians and stunt actors, broke underwear models and rich technocrats, lawyers and bankers and store clerks and ladies who lunch and everyone in between. This is really fun. People’s stories are a novelist’s raw materials, and I get to meet a breathtaking array of humankind.

My experience contradicts Dr. Peterson’s pedagogy. Truly successful artists have a masterful understanding of hierarchy. They see as a whole cloth how small parts fit into a larger whole; they see what is lesser and must be subsumed into what is greater. They’re also experts at structure and the discipline of their craft. Simultaneously, very successful non-artists foist a formidable creativity. They may wear a suit and tie instead of the t-shirt and jeans my husband favors, but their way with hedge funds or legal statutes or sound waves bespeaks an unlimited and inventive playfulness with the fundamentals of their field: creativity.

Recently, Sabin went abroad to make a 1:6 scale maquette for the WWI Memorial. Ultimately, the finished Memorial will be a 56 foot long, 10 foot high relief with 38 figures. All the figures fit into a unified narrative, all the small parts are ordered coherently into a greater whole to tell a story. It’s the hero’s journey from home through the hell of war and PTSD to a triumphal, and transformed, return home. It’s mesmerizing.

Fabricating the maquette, however, was an ordeal. The fabrication factory fancied itself as a “socialist collective of creativity.” But Sabin quickly discerned the truly capable workers. As Dr. Peterson correctly notes, when many people do something, some people do it better than others. The fabrication factory specialized in film props and collectibles. Collectibles are great fun, but they are not art. They are dolls. Sabin parried an argument every time he said, “Make the right leg longer than the left. It’s not a literal translation from life. The figure is perspectival.”

He eventually booted the doll-makers off the maquette. He sculpted alone out of his personal, unique vision, persisting until he accomplished a maquette of power, beauty, and dignity. World War I veterans have all passed, but they will be honored by “A Soldier’s Journey.” The beauty and dignity of Sabin’s National Memorial imbue it with value—which leads to some criticism of the capitalist system. All too often, mercenary collectors expect an artwork to stand somewhere and get more expensive. The dollar value is the “value” of the art. They miss the intangible qualities that make art valuable qua art.

The capitalist system also tends to corruption in the market-museum system. The separation between market and museum should be clean and distinct. Increasingly, it’s not. It’s expensive for a museum to mount an exhibit; a cunning gallery will underwrite that exhibition in order to promote their artists and to shore up the asking price for the artists’ work. This pleases collectors who have already bought works by the exhibited artist. Their investment is safe. However, new artists, or artists whose work is on the next wave of art history, are ignored by galleries and museums. Art is reduced to a commodity.

Reductive and heartless, the capitalist system can go too far. It often does. But the alternative is worse: state-sponsored art that confines the artist to a collective agenda. I see that happening now in Hollywood, where so many movies are vehicles for preaching propaganda, not for telling a story. It gets boring.

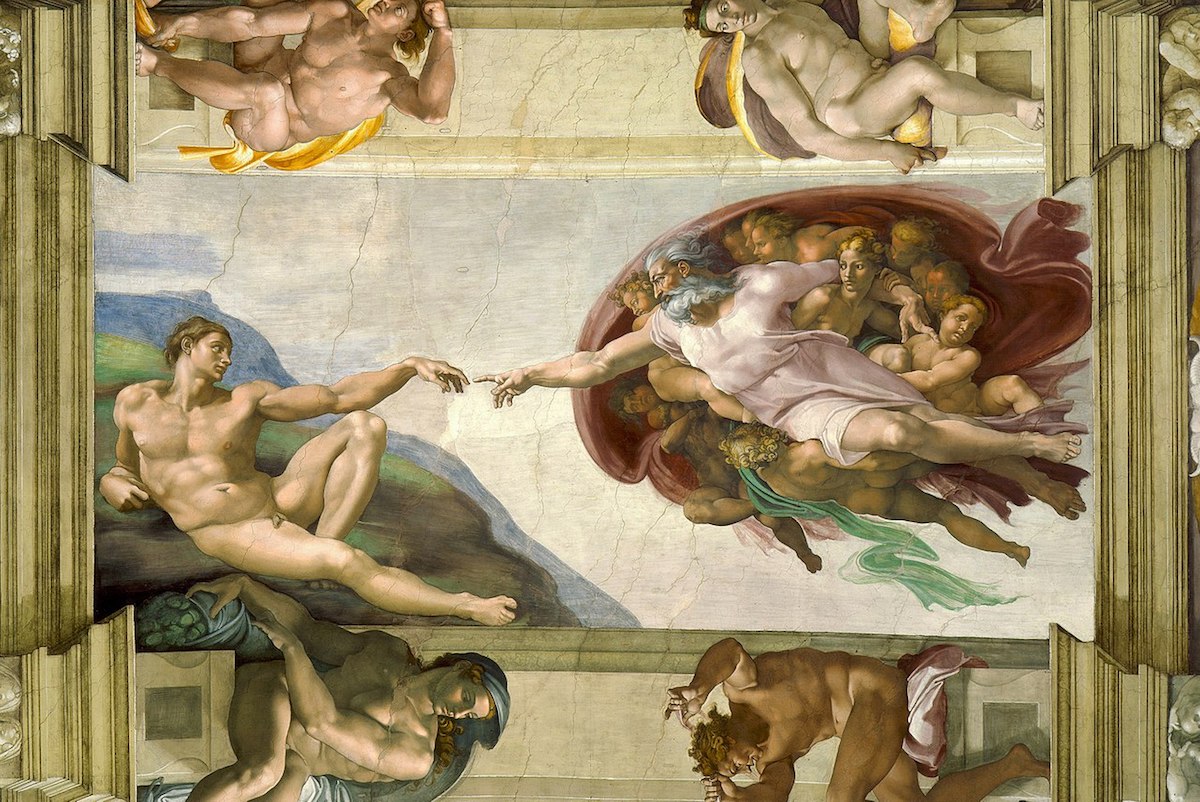

History is replete with examples of artists who stayed the course despite the slings and arrows of groupthink. Michelangelo, for example, my husband’s great reference, stuck with his vision despite potentially fatal disagreements with a murderous Pope. To the benefit of humanity, he resisted Papal input and adhered to his unique, personal vision. The Sistine Chapel resulted.

Great art is not collectivist. And artists aren’t necessarily left-wing.