The Final Artworks of 8 Famous Artists, from Frida Kahlo to Mark Rothko

The last artwork of a prominent artist can assume a near-mythic status. Take Frida Kahlo. What artistic concerns defined her twilight years? Did her work come to particular resolution, or reveal a perspective on human mortality? In fact, she painted watermelons—with a poignant nod to the end of her life inscribed into the flesh of the fruit.

In their final artworks, the eight artists below continued their commitments to the issues that shaped their careers, took risks, and meditated on existential questions.

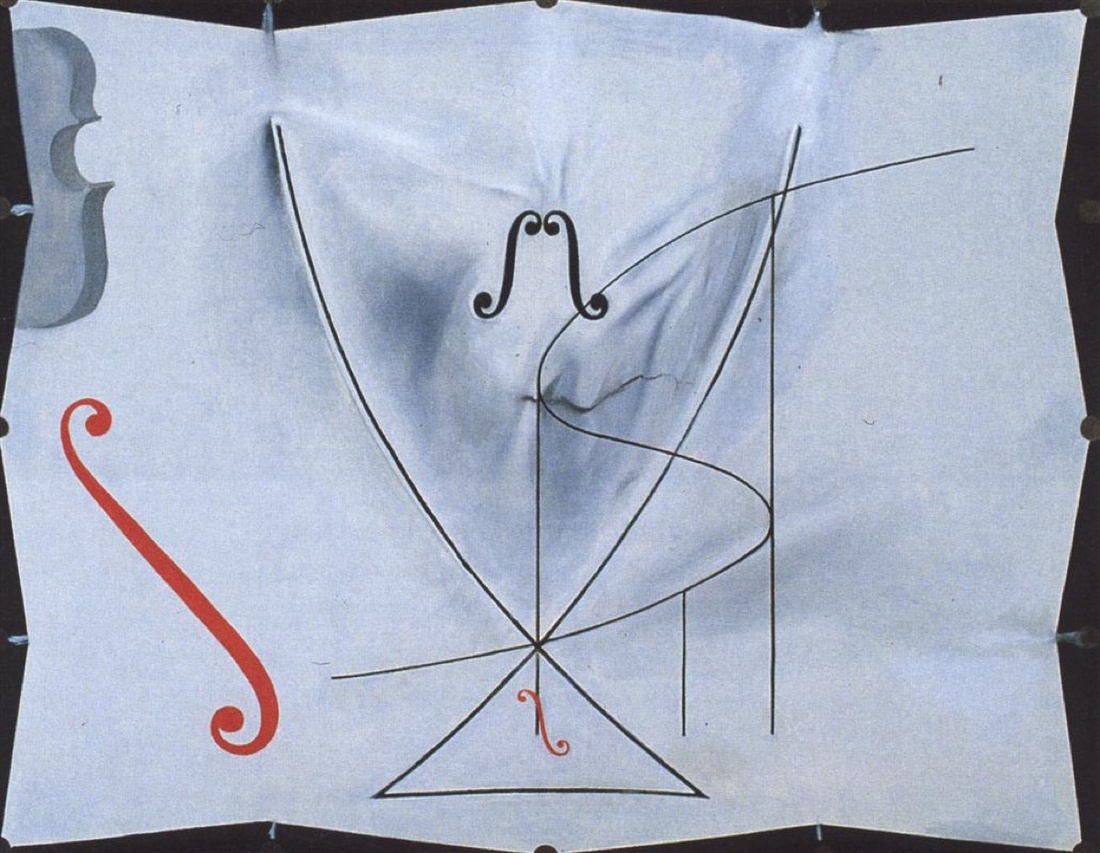

Salvador Dalí, The Swallow’s Tail, 1983

Salvador Dalí, The Swallow's Tail, 1983. Courtesy of the Dalí Theatre and Museum, Figueres, Spain.

Salvador Dalí, The Swallow's Tail, 1983. Courtesy of the Dalí Theatre and Museum, Figueres, Spain.

The perplexing works of Surrealist master Dalí are more readily associated with psychoanalysis and Freud than with mathematics. Yet his last painting (he may have created bronze works later, but issues surrounding their reproduction make their origins difficult to pinpoint) was inspired by the “catastrophe theory” formulated by 20th-century French mathematician René Thom. It attempted to predict the occurrence of abrupt phenomena in the world.

The theory appealed both to Dalí’s aesthetic sensibility and to his longtime fascination with time, as evidenced by his iconic melting clocks. The last work in a series related to the theory, The Swallow’s Tail references the shape of one of the graphs that Thom used to describe events in four dimensions. The symbolic cello at the painting’s top left is doleful, and Dalí—whose wife had passed away the previous year—combines anguish and allure in this last painting.

Marcel Duchamp, Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas, 1946–66

Marcel Duchamp, Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage . . . (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas . . . ), 1946-1966. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Estate of Marcel Duchamp. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Marcel Duchamp, Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d'éclairage . . . (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas . . . ), 1946-1966. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Estate of Marcel Duchamp. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

For two decades, the Dada pioneer of the readymade created his last artwork in secret—all while the public believed he had abandoned artmaking altogether. The installation work, an old door that opens onto a full-scale, 3D tableau, turns its viewers into voyeurs as they peek through the opening. While the door, which Duchamp procured from Spain, reprises his fondness for found objects, the tableau behind it is surprising in its intricacy and representational realism.

In the foreground, a naked female figure is splayed on a bed of twigs and leaves, holding a lit gas lamp. She appears to be the victim of a crime. The figure was composed of casts made from the bodies of Duchamp’s former lover and his second wife, in an unsettling tribute. Like a more sexually suggestive version of John Everett Millais’s Ophelia, the piece is at once disturbing and enchanting. Dubbed “the strangest work of art in any museum” by artist Jasper Johns, it was finally unveiled when it was moved from Duchamp’s New York studio to the Philadelphia Museum of Art after his death in 1968.

Frida Kahlo, Viva La Vida, Watermelons, 1954

Frida Kahlo, Viva la Vida, Watermelons, 1954. Photo by Jen Wilton, via Flickr.

Frida Kahlo, Viva la Vida, Watermelons, 1954. Photo by Jen Wilton, via Flickr.

While she may have painted the bulk of the composition somewhat earlier, Kahlo finished this still life, by adding the words “Viva la vida” to the meat of the watermelon wedge in the foreground, just eight days before her death. Meaning “Long live life,” the phrase has particular poignancy in this context. Below it, Kahlo wrote her name and the painting’s year and place of creation. Taken as a whole, the inscription both memorializes the artist’s existence and evokes her perseverance throughout a life of chronic physical pain. While exuberant in their colors and arrangement, the watermelons are traditionally associated with the Day of the Dead. The Mexican holiday is known to celebrate, rather than mourn, those who have passed on.

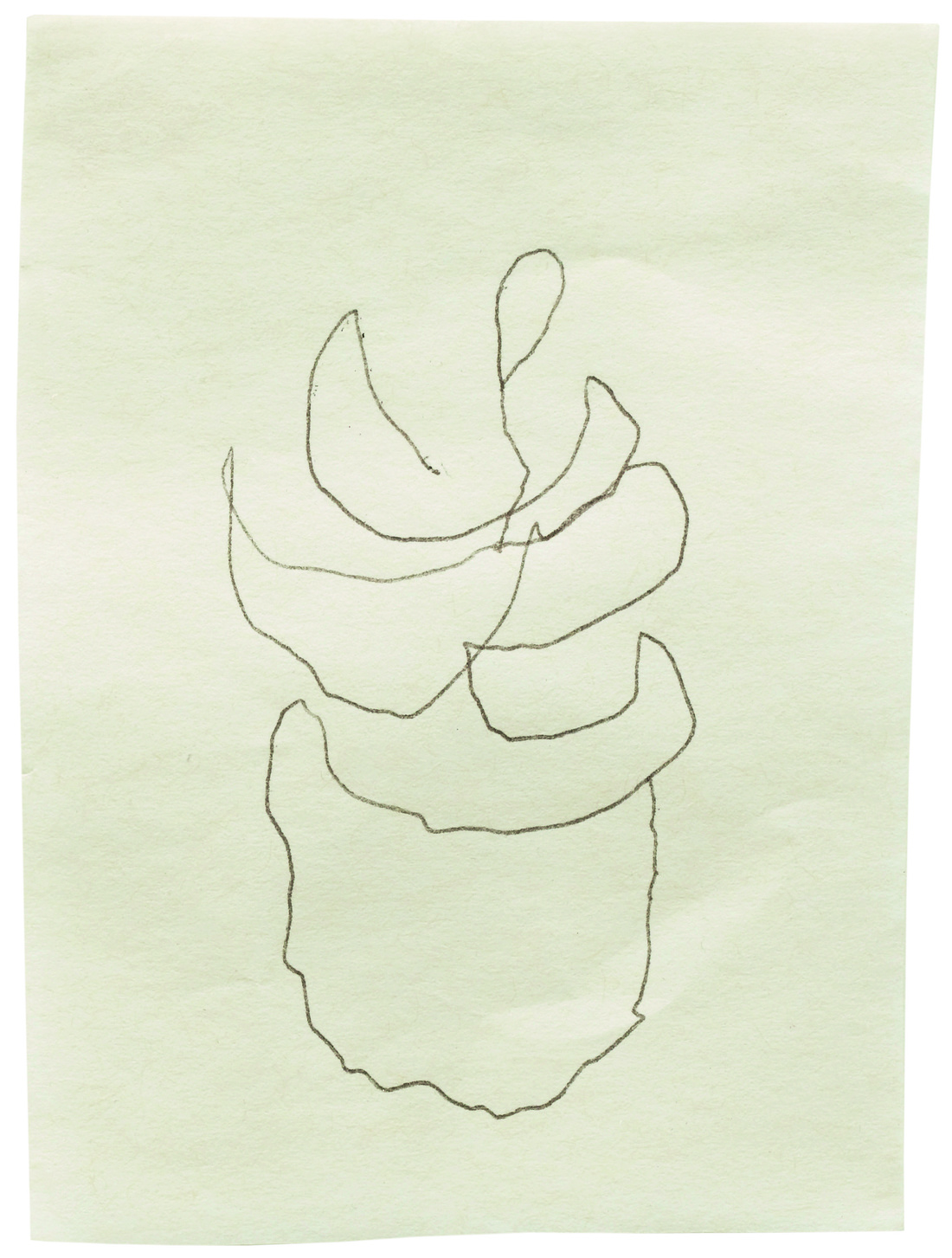

Agnes Martin, Untitled, 2004

Agnes Martin, Untitled, 2004. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

Agnes Martin, Untitled, 2004. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

An ink-on-paper work measuring not quite 10 inches square, the last drawing that Martin created before her death is curiously distinct from the geometric work she is known for. Still, the artist’s enduring fixation on lines and their spatial relationships comes through in the meandering, single-line drawing that resembles a potted plant. Likewise, Martin often captures subtle emotions in her work and, through the fragile line of the piece, a mental image surfaces of Martin at 92, drawing serenely. There is a peaceful quality to the composition, as well as a vitality that’s in step with Martin’s late paintings, in which she broke from subdued grids to render bolder shapes and colors.

Mark Rothko, Untitled 1970, 1970

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1970. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Mark Rothko, Untitled, 1970. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Rothko used large, rectangular swaths of color to express universal emotions, and his transfixing Color Field paintings are almost talismanic in the way they provoke empathy and awe. The Russian-American artist’s last painting is familiar in composition, with its stacked asymmetrical rectangles and limited color palette. Its bright-red hues, however, are notable in comparison with the more sober browns, blacks, and rusts that feature in many of Rothko’s preceding works. While vibrant, Untitled 1970has been seen as a harbinger of Rothko’s suicide of the same year, as its bold color is also evocative of blood.

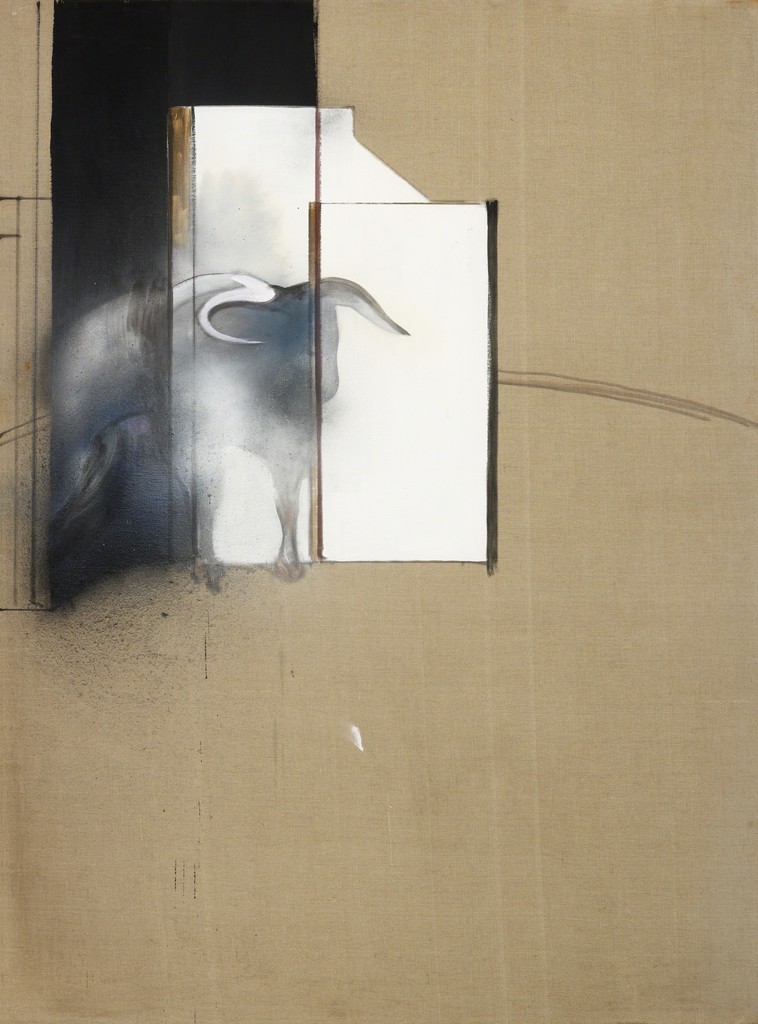

Francis Bacon, Study of a Bull, 1991

Last year, an art historian compiling a catalogue raisonné of Bacon’s oeuvre introduced his final artwork to the public after discovering it in a private collection in London. The piece reflects the British artist’s interest in bullfighting, a recurring motif in his work, but more so, it reads as a meditation on his own mortality. Having spent decades steeped in alcohol and debauchery, Bacon was in ailing health in his later years and knew he was approaching death by the time he painted Study of a Bull.

The bull, a common symbol of male virility, is faded and smudged, caught between the dark unknown and searing, white oblivion. While the bull lacks the usual contorted fleshiness of Bacon’s other figures, it carries a similar pathos and color palette. Bolstering the work’s evocation of death, Bacon incorporated dust from his studio into the composition, recalling the biblical “dust to dust.”

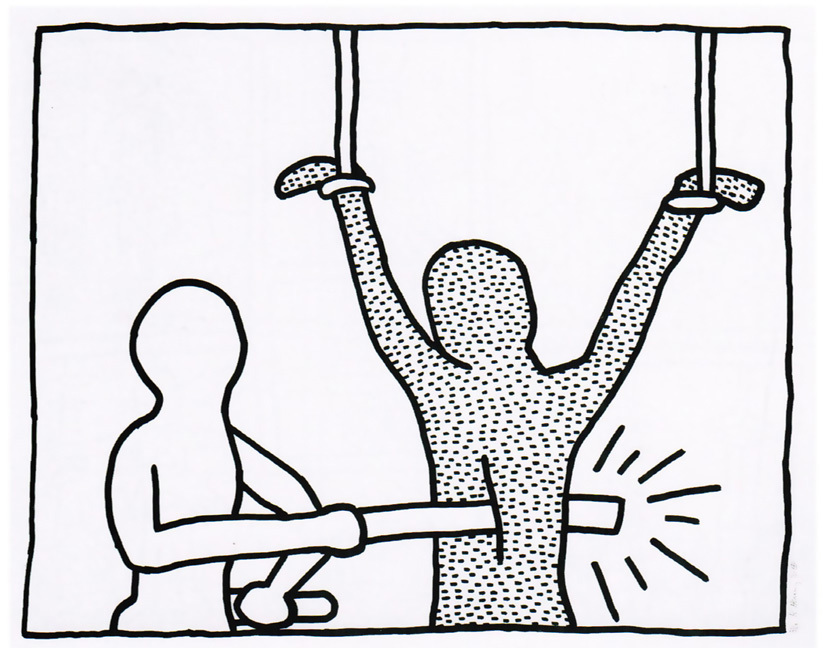

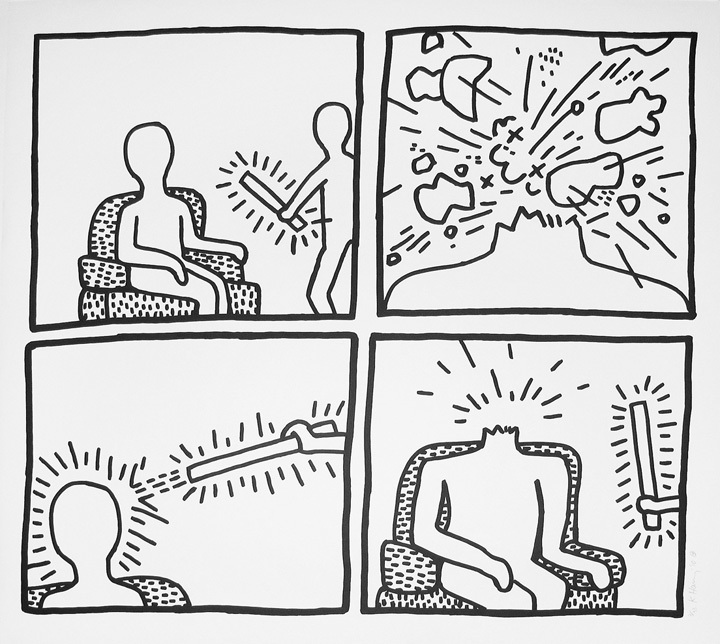

Keith Haring, The Blueprint Drawings, 1990

From 1980 to 1981, before shooting to fame, Haring created a suite of black-and-white Sumi ink drawings that were intended as blueprints from which to make copies. The drawings feature Haring’s signature pared-down lines and recurring motifs, including androgynous human figures, often engaged in violent or sexual acts; UFOs; dogs; and pyramids. In early 1990, Haring returned to the drawings he had created nearly a decade prior, turning them into a portfolio of screenprints. The drawings are both touching and urgent in the way they address same-sex love and the AIDS epidemic, and Haring made the portfolio just one month before his death from the disease.

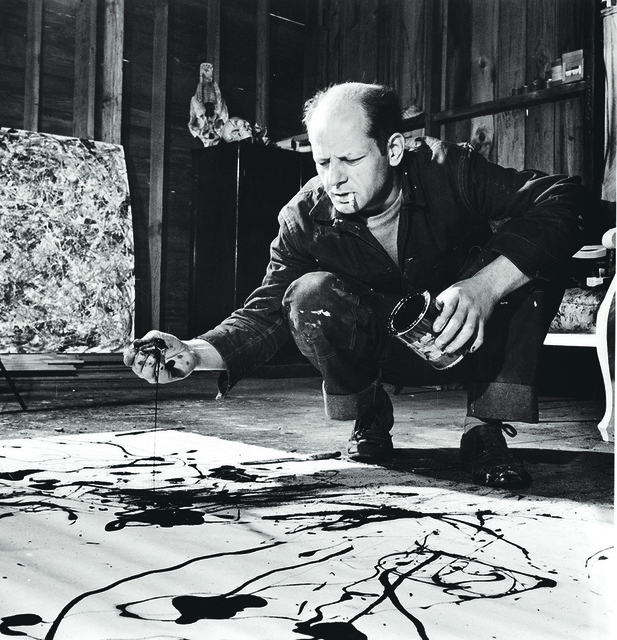

Jackson Pollock, Red, Black & Silver, 1956

Pollock’s purported last artwork has been embroiled in controversy over its authenticity for years. With its loose drips of red and cocoon-like blotch of black paint, the piece is, admittedly, a departure from the tighter drips and all-over chaos that typifies his work. Yet Ruth Kligman—Pollock’s lover who survived the car crash that took the artist’s own life in 1956—insisted the piece was genuine, and that the Abstract Expressionist artist created it as a gift for her shortly before he died.

Although the Pollock-Krasner Authentication Board still declines to vouch for the work (some have speculated this is due to allegiances to Pollock’s widow, Lee Krasner), forensic evidence that was found after Kligman’s death may support her claim. Along with Pollock’s hair and bits of sand from his local beach, the painting contains polar bear hair believed to be from Pollock’s polar bear rug.

—Rachel Lebowitz