A Dandy’s Guide to Decadent Self-Isolation

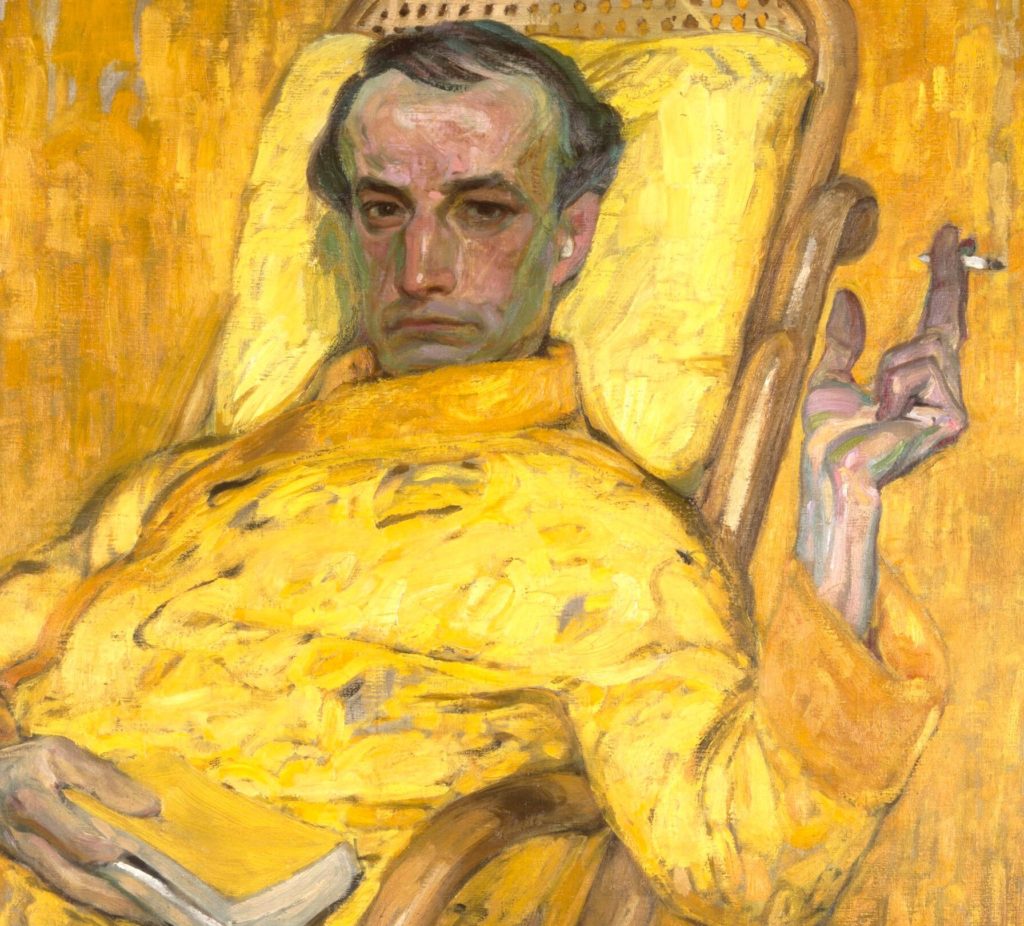

I’m not ashamed to say that I bought Joris-Karl Huysmans’s Against Nature because of the cover: Frantisek Kupka’s The Yellow Scale (Self-Portrait) from 1907 is an exhilarating study of the color yellow. Its human subject, slouched in a wicker armchair, a cigarette dangling from one hand while a single, louche finger marks the page of a book, could be the perfect image of Des Esseintes, the dissolute antihero of Huysmans’s novel. Strictly speaking, the painting is a self-portrait of the habitually mustached Kupka, but it bears more than a passing resemblance to Charles Baudelaire, who haunts almost every page of Against Nature. This novel, about a dyspeptic aesthete who “took pleasure in a life of studious decrepitude,” spends some two hundred pages luxuriating in excess and opulence while the hero cuts himself off from the rest of society.

An old idea that persists about the novel is that it ought to be morally instructive in some way, that it should teach us the correct way to live. Certainly, when Against Nature was published in French in 1884, much of the resultant hand-wringing was because Huysmans’s hero learns nothing new from his misadventures in self-isolation. The problem, according to Émile Zola, was “that Des Esseintes is as mad at the start as he is at the end, that there is no form of progression.” Barbey d’Aurevilly, who, depending on your point of view, was either a minor dandy in the Baudelaire coterie or just a nasty little pornographer, agreed: “Undertaken in despair, the book ends with a despair that is greater than that with which it began.” The reader is informed that in the flower of his youth, Des Esseintes often indulged in the pleasures of the flesh and the card table with his peers, but by the time we meet him in the first chapter, he has already begun dreaming of “a desert hermitage equipped with all the modern conveniences, a snugly heated ark on dry land in which he might take refuge from the incessant deluge of human stupidity.” Page after page, chapter after chapter, Des Esseintes throws more and more money after his ennui and deviant tastes. He flees the crowds of Paris for the country, cuts himself off from outsiders, and attempts to swaddle himself only in objects and experiences that meet his particular aesthetic principles. Decadent literature had its heyday in France in the nineteenth century when the poètes maudits sought to overthrow nature, replacing with it human genius and the pursuit of pleasure, no matter how perverted. But for all Des Esseintes’s extravagance, there is nothing that can stop the rot, there is no escaping his malaise. Eventually, he is ordered back to the city by a pragmatic doctor, where he must abandon his solitary existence and at least try to enjoy the same pleasures as other people. All Des Esseintes can manage, before the doctor strides out the door, is a petulant “But I just don’t enjoy the pleasures other people enjoy!” The novel ends with our hero slumped in a chair.

So, what, if anything, do we stand to learn about self-isolation from an ailing aristocrat at the tail end of the nineteenth century? Des Esseintes is based loosely on Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac, the dandy par excellence who was also the model for Proust’s Baron de Charlus. Proust’s roman-fleuve, and Huysmans’s Against Nature, like so many great novels, are concerned with the twilight of a once-golden age.

The dandy was an important figure in decadent literature, a visible manifestation of a society infected by its own opulence. Things rarely ended well for the dandy, whether fictional or historical: they tended to die in poverty and obscurity, their witticisms forgotten, their fashions surpassed. But for a few blazing decades of the nineteenth century, in fiction and in society, they were the absolute arbiters of taste, and Jean des Esseintes might just have been their high priest.

Curated from the pages of Against Nature, the following is a decadent guide to staying home in style. Quarantine, but make it “fun”-de-siècle.

VÊTEMENTS

A disastrous place to start. The array of “iso-outfits” and work-from-home ensembles that have been bandied about the internet would surely have pushed Des Esseintes to the brink. It goes without saying that you should not be wearing sweats; you probably should not even own any. Your wardrobe should be seasonal and thematic; you may wear your tweeds to an English-style tavern, but not along the boulevards. A workaround for the effort of daily dressing is to invest in a silk dressing gown, or a velvet smoking jacket, and simply throw it over whatever you are or are not wearing. Remember, though, that for a dandy, the primary aim of dressing is one’s own pleasure; impressing the petite bourgeoisie at the opera is just a secondary thrill. In the current climate, the “quarantini” hour is probably your best opportunity to earn a reputation as an eccentric. Try wearing “suits of white velvet with gold-laced waistcoats” or “sticking a bunch of Parma violets down [your] shirt-front in lieu of a cravat.”

BODY & MINDFULNESS

Even in his deepest despair, Des Esseintes never falls so low as to engage in anything resembling exercise. But just because you won’t catch him in a forearm plank doesn’t mean that you can’t take certain steps to take care of your body. As a dandy, you are encouraged to maintain a slender, rakish silhouette while young, but it is perfectly acceptable to become bloated and syphilitic as you grow older. You needn’t worry about flossing or brushing your teeth, either. Simply follow the example of Robert de Montesquiou and hold a gloved hand in front of your rotting maw whenever smiling in public.

Routine is important: our protagonist recommends selecting a daily menu for each season that should never be changed. Here’s Des Esseintes’s winter meal plan and sleep schedule, which can be tweaked as needed: “At five o’clock in winter, after dusk had fallen, he ate a light breakfast of two boiled eggs, toast and tea; then he had lunch about eleven, drank coffee or sometimes tea and wine during the night and finally toyed with a little supper about five in the morning, before going to bed.”

If you’re feeling snacky, then Des Esseintes recommends a hearty enema, the recipe for which is as follows: 1oz cod-liver oil, 7oz beef tea, 7oz red wine (preferably Burgundy), and the yolk of one egg. Those with a sweet tooth are advised that the best violet bonbons to be found in Paris are made by the chocolatier and librettist Monsieur Paul Siraudin, at his store on the corner of Rue de la Paix and Place Vendôme.

Many people have reported difficulty sleeping, an inability to concentrate, or “a mood of splenetic indecision.” To cure such complaints, Des Esseintes recommends a course of soporific literature before bed: “Read those books that are so charmingly adapted for convalescents and invalids, whom more tetanic or phosphatic works would only fatigue: the novels of Charles Dickens.”

INTERIOR DESIGN

Perhaps the most important element of the decadent guide to staying at home. First, you’ll need enough inherited wealth that you don’t actually need to work. Ideally, you’ll also want a modest acreage outside the city to avoid contagion from the masses. From there, your home is really what you make of it. Any space, no matter how dingy or rented, can be transformed with a bold aesthetic vision: “as a matter of fact, artifice was considered by Des Esseintes to be the distinctive mark of human genius.” White walls, framed movie posters, and IKEA bookcases are fine, but have you considered turning your dining room into a ship’s cabin? Try a “ceiling of arched beams, bulkheads and floorboards of pitch-pine, and a little window-opening that lets into the wainscoting like a porthole.” Replace those flat-pack formica bookcases with built-in ebony shelving. For floor coverings, tiger skins and blue fox furs work best. In terms of original art, Odilon Redon etchings can be found online, but copper engravings by Jan Luyken are harder to come by. When in doubt, Gustave Moreau should be in the center of your mood board.

When it comes to decorating the bedroom, there are only two options: “you could either make it a place for sensual pleasure, for nocturnal delectation, or else you could fit it out as a place for sleep or solitude, a setting for quiet meditation, a sort of oratory.”

White walls are out; rooms draped in scarlet tapestries are in. If you’re thinking of giving your apartment a lick of paint, or exploring the possibility of a feature wall, the first chapter of Against Nature will help you choose a decadent color: stay away from all shades of purple (except plum) because they lose their luster in candlelight. In fact, your guiding principle should be to always select colors that “appear stronger and clearer in artificial light.” If you, or someone you live with, is best described as a “gaunt, febrile creature of feeble constitution” then Des Esseintes urges you to resist the temptation of the “most morbid and irritating of colours,” orange—it flares up to an unflattering fiery nasturtium-red by lamplight.

Finally, all dandies know that you need a statement piece that will gesture to your exquisite but slightly outré taste, while also tying the room together. It’s tricky, and usually expensive. Des Esseintes opted for a live tortoise whose gilded shell was festooned with jewels; thanks to Bulgari and Francesco Vezzoli, his dream could also be yours.

TRAVEL

When it comes to travel, Des Esseintes has a few pearls of wisdom for those of us feeling housebound. He reminds us that travel itself, the moving between places, is no fun at all, and that any pleasure we might pretend to derive from it exists “only in recollection of the past and hardly ever in the experience of the present.” The whole travel thing is “a waste of time,” because “the imagination can provide a more-than-adequate substitute for the vulgar reality of actual experience.”

There are many ways to simply imagine travel: start by putting up “a series of colour-prints on the wall, such as you see in packet-boat offices and Lloyd’s agencies, representing steamers bound for Valparaíso and the River Plate.” Then, re-create a risk-free experience of strolling the deck of a cruise ship by “salting your bath-water and adding sulphate of soda with hydrochlorate of magnesium and lime in the proportions recommended by the Pharmacopoeia” then “taking out a ball of twine or a twist of rope, bought for the occasion from one of those enormous roperies whose warehouses and cellars reek with the smell of the sea and sea-ports.” Breathe it all in, and let your mind do the rest.

Des Esseintes would also advise against setting out for a dream destination once the quarantine is lifted, as it’s highly unlikely your expectations will be met. Having long held a fascination for Holland, Des Esseintes once visited the land of Rembrandt. There, he expected to find “patriarchal simplicity and riotous joviality,” and, to be frank, he would have settled for “wild revelry or domestic drunkenness,” but the trip proved a bitter disappointment. Begrudgingly, he “had to admit that the paintings of the Dutch School exhibited in the Louvre had led him astray.”

HOUSEPLANTS & FLOWERS

Houseplants and flowers are nonnegotiable, but steer clear of “stupid flowers such as the rose, whose proper place is in pots concealed inside porcelain vases painted by nice young ladies.” Why not turn your apartment into a hothouse? Fill it with languorous, exotic plants from the tropics and flowers of tremulous delicacy. Sure, ZZ plants and devil’s ivy are easy to care for in a low-light situation, but ask yourself, are they “princesses of the vegetable kingdom, living aloof and apart, having nothing whatever in common with the popular plants or the bourgeois blooms?” Try a drosera or an amorphophallus instead.

If you’re not much of a green thumb (and full disclosure, it took a team of horticulturists to put together our hero’s hothouse), then you might be tempted to spruce up your place with fake plants. It’s a good thought, but a true dandy like Des Esseintes would take the concept one step further: “tired of artificial flowers aping real ones, he wanted some natural flowers that would look like fakes.”

DATING & SEX

Like travel, this isn’t something you need to worry about too much as a self-isolating dandy. You ought to have debauched yourself in your early youth to the point of venereal infirmity, and now, the erotic life should leave you indifferent. If you are as decadent as Des Esseintes, this is a good thing. Why not get together on Zoom with the rest of your single friends, and hold a somber dinner party to bid farewell to your libido? You’ll need a dining room draped in black that opens out “to a garden metamorphosed for the occasion, the paths being strewn with charcoal, the ornamental pond edged with black basalt and filled with ink, and the shrubberies replanted with cypresses and pines.” The menu might take some coordinating, but it should consist of “turtle soup, Russian rye bread, ripe olives from Turkey, caviar, mullet botargo, black puddings from Frankfurt, game served in sauces the colour of liquorice and boot-polish, truffle jellies, chocolate creams, plum-puddings, nectarines, pears in grape-juice syrup, mulberries and black-heart cherries.”

WHAT TO READ

There’s only really one title in English that Des Esseintes can recommend, and that’s Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. For an immersive experience, you could read it in your ship’s cabin-cum-dining room, or while sniffing that twist of rope you bought earlier. Our hero also has strong feelings about Latin literature, so if you only ever read one Roman text, make it Petronius’s Satyricon. Baudelaire’s entire oeuvre is required reading, and from there you can branch into the poetry of Verlaine and Mallarmé. There is no reason to believe that Des Esseintes ever read a work written by a woman. If you, like Des Esseintes, feel strongly that “when the period in which a man of talent is condemned to live is dull and stupid, the artist is haunted, perhaps unknown to himself, by a nostalgic yearning for another age,” you will prefer Flaubert’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony over the tawdry Madame Bovary. There’s a lot of prevarication when it comes to Balzac’s Comédie Humaine: the sprawling body of work has its merits, but there came a point for Des Esseintes when “he no longer opened Balzac’s books; their healthy spirit jarred on him.”

Which brings us to the most important point about books: it’s essential for a dandy to collect them, and maybe even write them, but the reading of them is not altogether necessary. Special attention should be paid to bindings and editions, however. At a bare minimum you should be purchasing hardcovers, and where possible, leather-bound books. You’ll be slouching in your armchair for some time yet; you want those uncracked spines to look winsome in the artificial light.

Samuel Rutter is a writer and translator from Melbourne, Australia. His work has appeared in A Public Space, The White Review, T Magazine, and Harper’s. He is currently writing his first novel.