Art

How Op Artists of the 1960s Created Their Hallucinatory Effects

Bridget Riley

Forum Auctions

According to ancient Greek legend, the artist Zeuxis, who lived around the 5th century B.C., rendered grapes so realistically that birds flew into his painting in attempts to eat the fruit. People have enjoyed such painterly illusions for millennia. Artists have manipulated color, shape, and form to trick viewers into seeing depth on a two-dimensional plane (the prominent artistic technique called trompe l’oeil literally means “trick the eye”). Such deception and perceptual games are the point of the modern

(or “Op art”) movement. (Notably,

and Op art are often linked: The former designation declares a work’s real, instead of perceived, movement.)

Around the 1960s, artists from around the world such as

(Germany/America),

(Israel),

(Venezuela),

(Venezuela),

(United Kingdom), and

(France/Hungary) began using color theory and geometric principles to create optical illusions. Typical works from the era are either bright or stark black-and-white, with graphic shapes that appear to oscillate or swirl, fooling viewers into seeing movement and change within static paintings or prints.

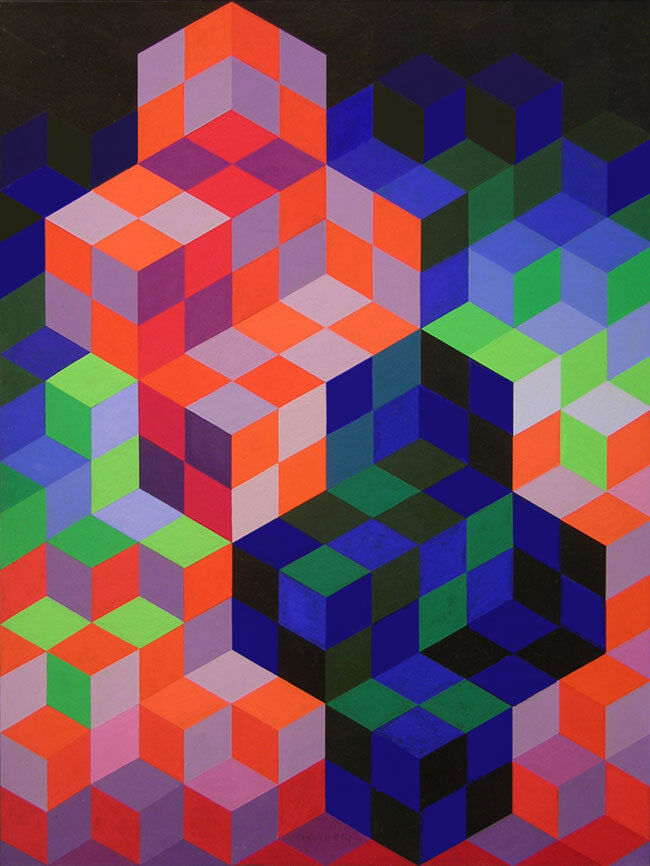

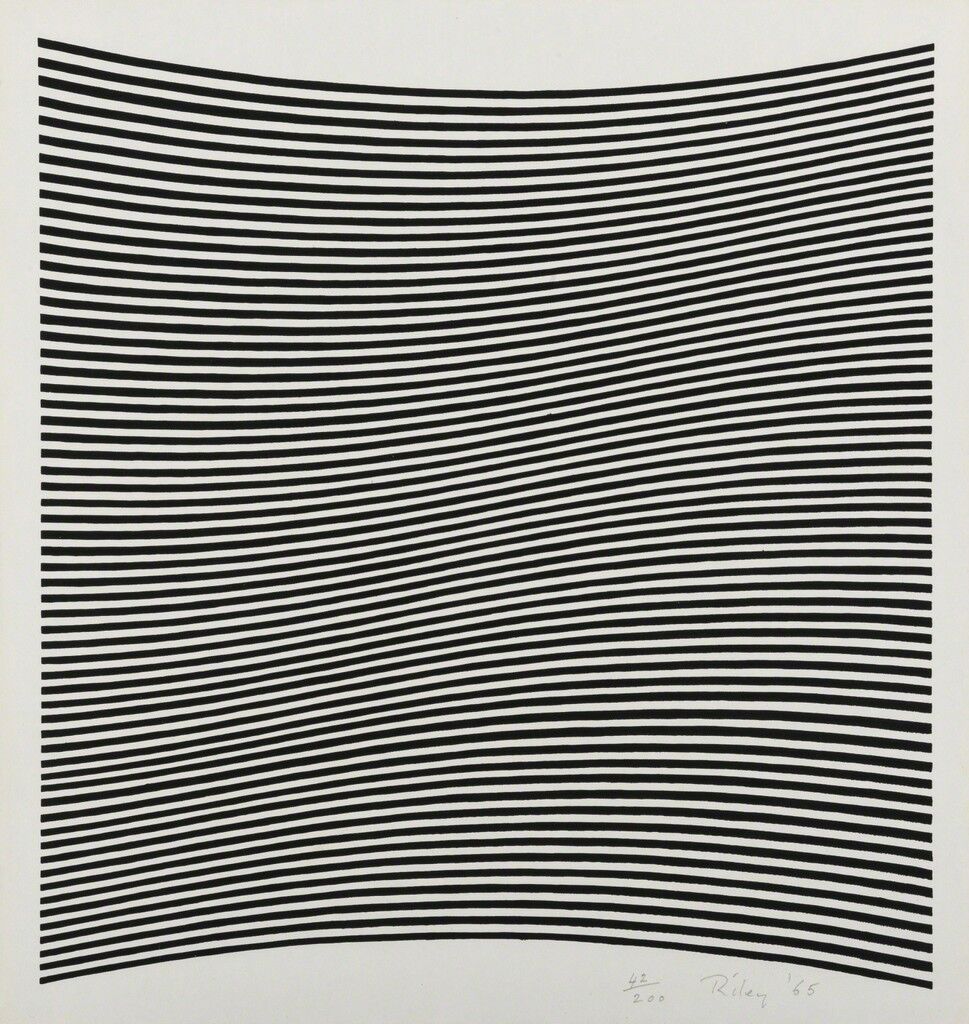

In Riley’s Untitled (La Lune en Rodage – Carlo Belloli) (Schubert 6) (1965), for example, the artist renders a series of horizontally oriented, curved black lines so close together that they seem to vibrate. For Duo-2 (1967), Vasarely painted a series of linked squares in alternating bright (orange, chartreuse) and dark (navy, mauve) hues. The result: stacks of three-dimensional cubes that appear to advance and recede. Many Op artworks recall the drawings of

: impossible patterns that, rendered in two dimensions, subvert perspectival rules.

In 1965, curator William C. Seitz mounted “The Responsive Eye” at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, a group exhibition that gathered the day’s leading Op artists. Seitz posited that the movement’s origins lay in

, which had celebrated artists’ unique perceptions of the world around them, and therefore suggested that a single, common visual experience of the world is mere myth.

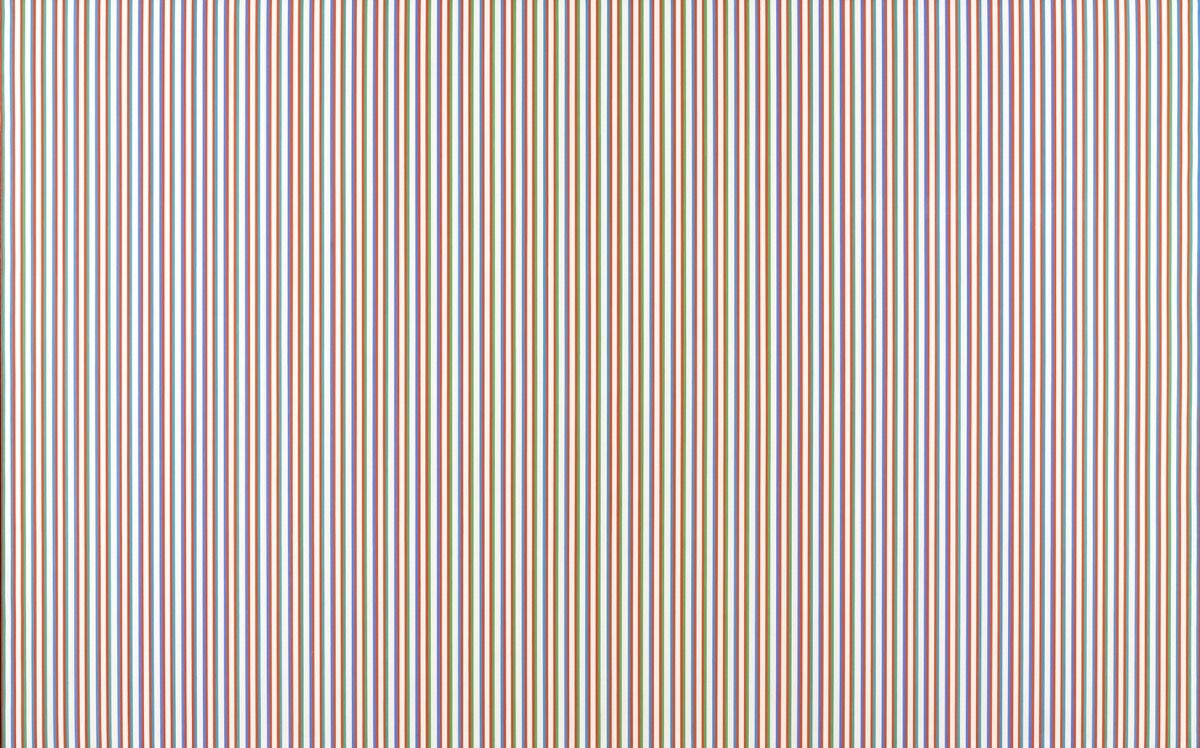

Bridget Riley, Late Morning, 1967-8. © Bridget Riley 2018. Courtesy of Tate Liverpool.

By featuring artworks by American artists like Frank Stella,

, and

alongside works by Riley, Cruz-Diez, and Albers, “The Responsive Eye” proposed a direct lineage between American abstraction and global Op art. According to Seitz’s catalogue, “the establishment of abstract painting has made it permissible for color, tone, line, and shape to operate autonomously.” In other words, Op art developed from Impressionist ideas and abstract techniques.

Albers’s experiments and writings on color theory offered another source of inspiration for Op artists. The nested squares of varying hues featured in his own works propose that color is always relative: We perceive a color differently depending on the other colors and shapes that surround it.

In 2016, New York’s El Museo del Barrio offered a counterpoint to “The Responsive Eye,” highlighting Latin American artists’ roles in Op art. The exhibition, entitled “The Illusive Eye: An International Inquiry on Kinetic and Op Art,” included work by

,

,

, and others Seitz had left out. In a review of the show for the New York Times, Ken Johnson underscored how midcentury critics such as Clement Greenberg had dismissed Op art as gimmicky. El Museo del Barrio instead attempted to elevate the movement by linking it to mysticism and more erudite concepts.

This past July, Tate Liverpool opened “Op Art in Focus,” an exhibition spanning the 1960s to today (it’s on view through June 16, 2019). “To me,” said curator Darren Pih, “it is a movement that speaks to a more technologically connected world, when technology and art were being fused to create new ways of seeing.”

Lygia Pape

Sem título, 1959/1960

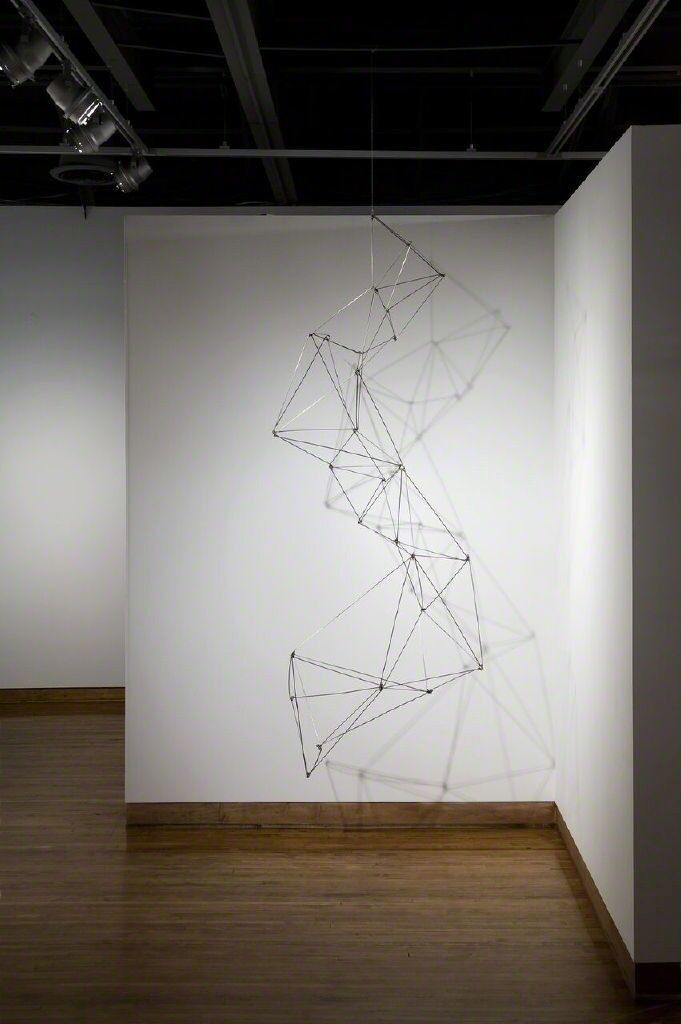

Gego

Reticularea, 1969-1970

Indeed, questions about how we see and what tools can help us see better extended across disciplines. In 1960 alone, American scientist Theodore Maiman created the first laser, while Eleanor J. Gibson and R.D. Walk developed the “visual cliff” study, which tested how infants perceive visual depth.

In an exhibition of 26 works, Pih has included eight by Riley. They range from energetic, buzzing screen prints of zigzagging, black-and-white lines (Untitled [Fragment 1/7] and Untitled [Fragment 3/11], both 1965, for instance) to Late Morning (1967–68), a painting comprised of colorful, vertical lines on canvas. “Her work is immediately recognizable and somehow symptomatic of the technologically-enabled acceleration associated with the 1960s,” said Pih (indeed, Late Morning recalls the static of a television screen). “Yet her work is also rooted in art history and in early movements such as

.”

Pih also connected Riley to

, who experimented with “mechanized optics” decades before Op art emerged. Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, the French artist made discs printed with concentric circles. When spun on a motorized platform, they created hypnotic, gyrating pictures that fooled the viewer into thinking the images themselves were moving. (Since these works actually spun, we might consider them an example of both Op and Kinetic art.)

Yet Op art is very much a product of the 1960s. The bright, graphic colors and shapes recall the day’s mod fashion styles. And the movement’s concerns with perception interacted with the decade’s mind-altering drugs of choice: LSD and mescaline could literally change the way that people saw and experienced shapes and colors.

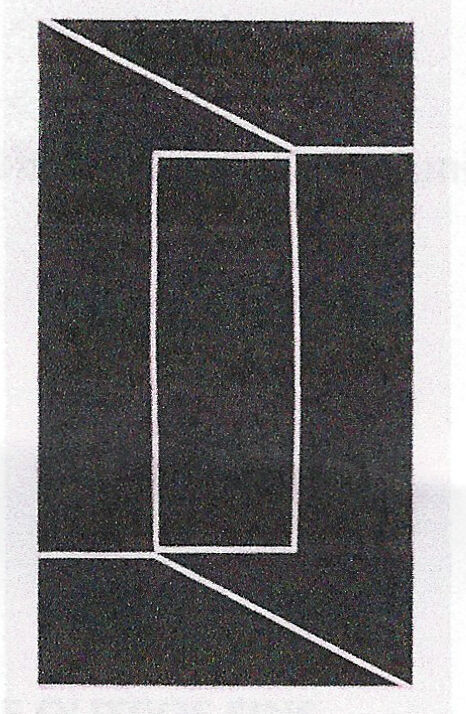

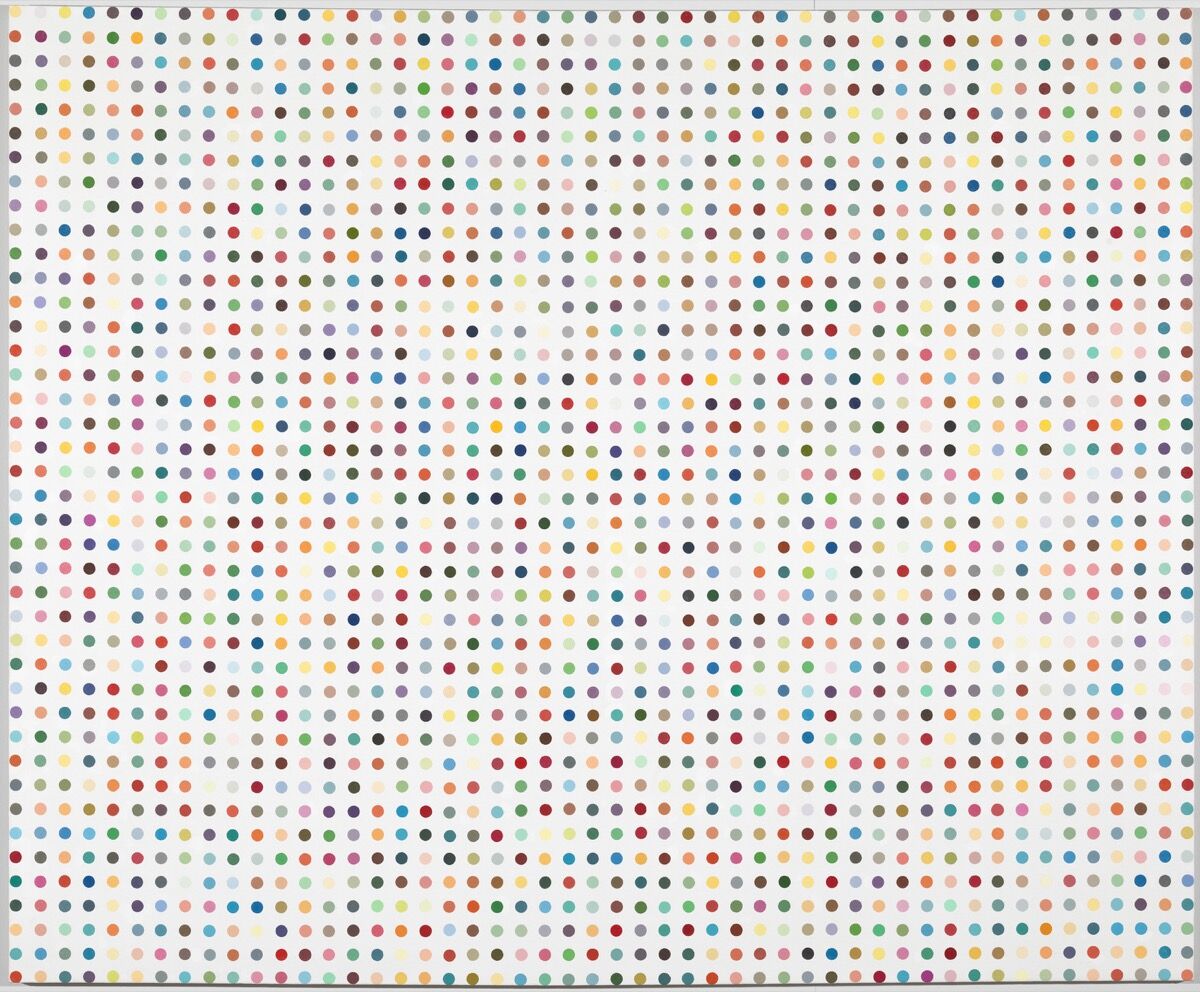

Damien Hirst, Anthraquinone-1-Diazonium Chloride, 1994. © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. / DACS 2018. Photo by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Courtesy of Tate Liverpool.

“Mescalin [sic] raises all colors to a higher power and makes the percipient aware of innumerable fine shades of difference, to which, at ordinary times, he is completely blind,” Aldous Huxley wrote in his influential 1954 bookThe Doors of Perception, in which he documented an acid trip. Huxley also noted “red surfaces swelling and expanding from bright nodes of energy that vibrated with a continuously changing, patterned life.” In many ways, Op art formalized such intense visual experiences.

Yet Op art has continued to influence contemporary painting and sculpture, as well. In the Tate Liverpool show, Pih included Aluminium 4 (2012) by Canadian artist

: a group of four aluminum boxes displayed on the floor that radiate different hues of light. A specialized light system infuses the cubes with more than 16 million color permutations. With contemporary technology, Bulloch further extends her predecessors’ project of demonstrating color’s near-infinite possibilities.

A

spot painting, Anthraquinone-1-Diazonium Chloride(1994), is also on view. From 1986 through 2011, the British artist made over 1,000 such artworks: paintings comprised of colored, evenly-spaced dots against a white background (the dimensions of the dots and canvases vary across the series). Yet Hirst is better known for his attention-grabbing feats—exhibiting a shark in a tank of formaldehyde; setting auction records for mass-produced artworks—than for carefully considering the laws of human perception.

“Of course, Hirst isn’t usually understood in the context of Op Art,” Pih admitted. “But, formally, the ‘spot’ paintings have the dazzle effect.” While the title of the work refers to a pharmaceutical compound, the painting’s execution “takes the form of mechanical and unemotional

paintings,” he observed. Antidepressants and opioids have, arguably, replaced LSD and mescaline as today’s mind-altering substances of choice (though to be fair, “microdosing,” or taking small amounts of LSD, is making a comeback). Artists’ perceptions of color, form, and the world around them have, perhaps, changed accordingly.

Alina Cohen is a Staff Writer at Artsy.