A Surging Auction Market Points to Korean Minimalism as the Next Gutai

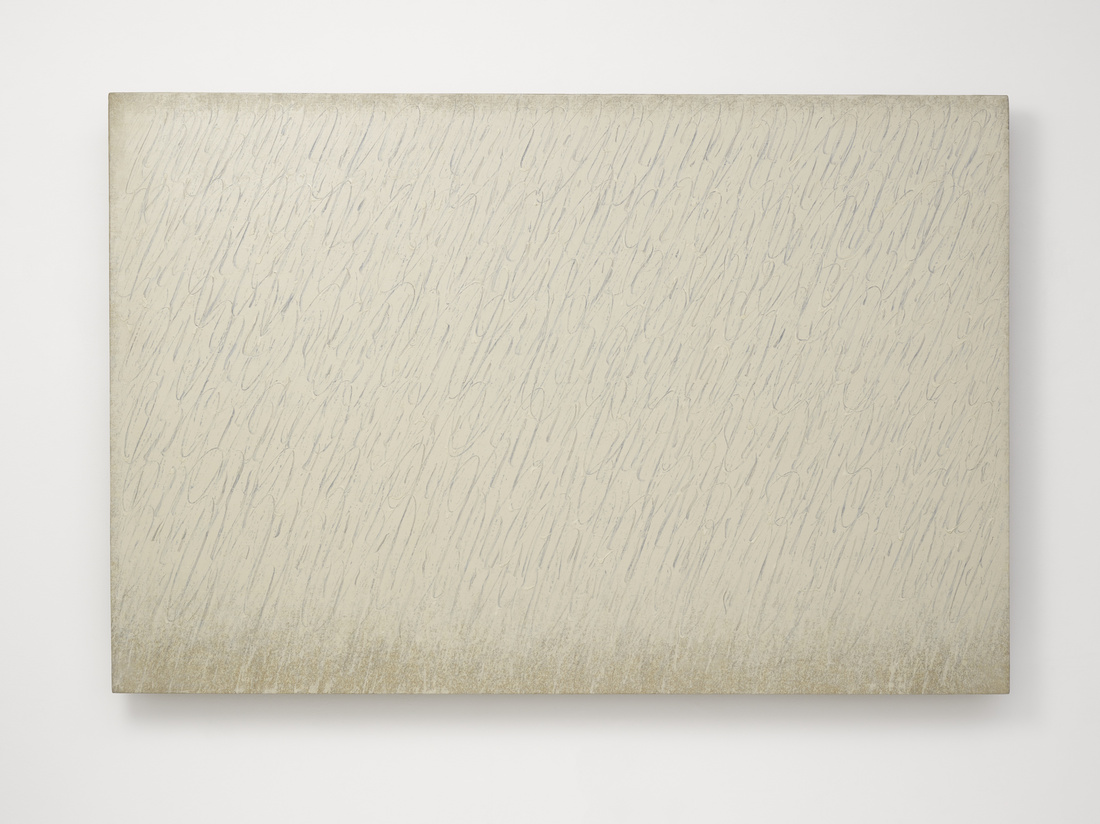

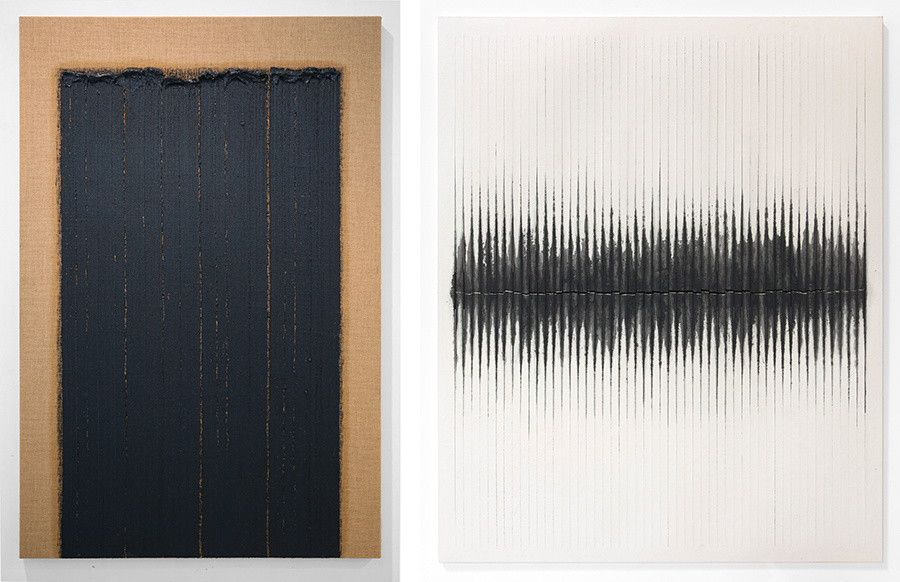

With its repetitious distinct strokes and monochrome palette, South Korean painter Park Seo-Bo’s first British solo exhibition, at White Cube Mason’s Yard, bears a passing resemblance to the gridded canvases of American abstract minimalist Agnes Martin.

But while the similarity might be superficial—given the artists’ disparate backgrounds—the collision of these two cultures has had profound recent repercussions in the art market. Ahead of the White Cube opening this week, a key dealer noted that primary prices for Park and related artists have surged by up to 200% since September 2014. It is part of an ongoing fascination with Dansaekhwa (also transliterated as Tansaekhwa)—translated literally as “monochrome painting”—a loose group of Korean artists who are increasingly popular among buyers seeking underappreciated work to complement existing collections.

This week, Los Angeles’s Blum & Poe opens “Dansaekhwa and Minimalism,” what the gallery calls the first survey of Korean monochromatic painting with American Minimalism, featuring work by Park, Martin, and Sol LeWitt. In February, Seoul space Kukje Gallery will present a solo exhibition by Chung Chang-Sup, another leading Dansaekhwa artist, and will also team up with the Boghossian Foundation on a group show of Dansaekhwa at the historic Villa Empain in Brussels, the first major show of its kind in Belgium.

“I think it’s inevitable that at the moment there is a general interest on the part of dealers and collectors to look at work by artists who have gone underappreciated and undervalued for a long time,” said Katharine Kostyal, curator of the White Cube show, “Ecriture 1967-1981.” “[It is a] move away from this obsession with the new, and always buying the latest youngest artist, and mining recent history.”

But while the similarity might be superficial—given the artists’ disparate backgrounds—the collision of these two cultures has had profound recent repercussions in the art market. Ahead of the White Cube opening this week, a key dealer noted that primary prices for Park and related artists have surged by up to 200% since September 2014. It is part of an ongoing fascination with Dansaekhwa (also transliterated as Tansaekhwa)—translated literally as “monochrome painting”—a loose group of Korean artists who are increasingly popular among buyers seeking underappreciated work to complement existing collections.

This week, Los Angeles’s Blum & Poe opens “Dansaekhwa and Minimalism,” what the gallery calls the first survey of Korean monochromatic painting with American Minimalism, featuring work by Park, Martin, and Sol LeWitt. In February, Seoul space Kukje Gallery will present a solo exhibition by Chung Chang-Sup, another leading Dansaekhwa artist, and will also team up with the Boghossian Foundation on a group show of Dansaekhwa at the historic Villa Empain in Brussels, the first major show of its kind in Belgium.

“I think it’s inevitable that at the moment there is a general interest on the part of dealers and collectors to look at work by artists who have gone underappreciated and undervalued for a long time,” said Katharine Kostyal, curator of the White Cube show, “Ecriture 1967-1981.” “[It is a] move away from this obsession with the new, and always buying the latest youngest artist, and mining recent history.”

According to historical auction data, paintings from Park’s “Ecriture” series dated to the 1970s, of a comparable size to some work featured in the White Cube show, sold at auction as recently as December 2014 for $55,432. A work of a comparable size and date sold in November 2015 for $838,633. Auction records for key Dansaekhwa artists including Park, Chung Sang-Hwa, Yun Hyong-Keun, Chung Chang-Sup, and Kwon Young-Woo have all been broken in the last four months.

Kostyal attributed much of the credit for this to the Korean galleries who have “done an enormous amount to promote this group of artists to bring their work to greater attention.” Hyun-Sook Lee, founder and chairwoman of Kukje said that when her gallery opened in 1982 “there was no domestic art market in Korea,” but since the 1990s, when international art made inroads, she has “been looking forward to the right opportunity to introduce modern Korean artists” to an international audience. The gallery achieved this partly through a much-praised Dansaekhwa exhibition at the Venice Biennale last year, a joint effort with the Boghossian Foundation and New York’s Tina Kim Gallery. “We expect that interest in the movement will only continue to grow in 2016,” said Kim in an email.

Such attention comes after decades of neglect. As Guggenheim Museum curator Alexandra Munroe wrote in an essay on the occasion of a 2014 Dansaekhwa show at Kukje, “Dansaekhwa has long been recognized as one of the most influential art movements in the history of contemporary Korean art…but it is only recently that the movement has sparked new attention abroad.” In part, she puts this down to the “return of abstract painting” mirrored by other recent rediscoveries of abstract art trends including Japanese Gutai and Europe’s Zero movement, both of which experienced market booms. According to a September 2015 article in the New Yorker, Dansaekhwa “has several advantages over Gutai, including abundance,” and is advantageous because it is relatively affordable as an alternative to Western minimalism and its artists continue to make work, create almost exclusively painting, and have strong art historical pedigrees.

Kostyal attributed much of the credit for this to the Korean galleries who have “done an enormous amount to promote this group of artists to bring their work to greater attention.” Hyun-Sook Lee, founder and chairwoman of Kukje said that when her gallery opened in 1982 “there was no domestic art market in Korea,” but since the 1990s, when international art made inroads, she has “been looking forward to the right opportunity to introduce modern Korean artists” to an international audience. The gallery achieved this partly through a much-praised Dansaekhwa exhibition at the Venice Biennale last year, a joint effort with the Boghossian Foundation and New York’s Tina Kim Gallery. “We expect that interest in the movement will only continue to grow in 2016,” said Kim in an email.

Such attention comes after decades of neglect. As Guggenheim Museum curator Alexandra Munroe wrote in an essay on the occasion of a 2014 Dansaekhwa show at Kukje, “Dansaekhwa has long been recognized as one of the most influential art movements in the history of contemporary Korean art…but it is only recently that the movement has sparked new attention abroad.” In part, she puts this down to the “return of abstract painting” mirrored by other recent rediscoveries of abstract art trends including Japanese Gutai and Europe’s Zero movement, both of which experienced market booms. According to a September 2015 article in the New Yorker, Dansaekhwa “has several advantages over Gutai, including abundance,” and is advantageous because it is relatively affordable as an alternative to Western minimalism and its artists continue to make work, create almost exclusively painting, and have strong art historical pedigrees.

“Everyone of [Park’s] generation was profoundly affected by the horrors of the Korean war,” said Kostyal. “He chose, as his colleagues did as well, almost to turn his back on the world and make art that was fundamentally introspective. It was a healing process for them. And that’s partly because there was very little expectation that these works would have a very large audience.”

Looking forward to this year, as this resurgence has shown, the market is notoriously hard to predict. Is there much left to do? “It’s still difficult for people,” said Blum & Poe co-founder Tim Blum. “It’s not like it’s being absorbed quickly. Not everyone knows about it by any stretch of the imagination. [But] it’s heading in that direction.”

A spokeswoman for Blum’s gallery highlighted a 100-200% increase in primary prices since September 2014 for Park, Ha Chong-Hyun, Chung Sang-Hwa, Yun Hyong-Keun, and Kwon Young-Woo, though Blum said that the large number of recent exhibitions for the most popular members of the group might be considered “overly eager.” From now on, he added, “it comes down to distinguishing what’s what, the quality.”

Looking forward to this year, as this resurgence has shown, the market is notoriously hard to predict. Is there much left to do? “It’s still difficult for people,” said Blum & Poe co-founder Tim Blum. “It’s not like it’s being absorbed quickly. Not everyone knows about it by any stretch of the imagination. [But] it’s heading in that direction.”

A spokeswoman for Blum’s gallery highlighted a 100-200% increase in primary prices since September 2014 for Park, Ha Chong-Hyun, Chung Sang-Hwa, Yun Hyong-Keun, and Kwon Young-Woo, though Blum said that the large number of recent exhibitions for the most popular members of the group might be considered “overly eager.” From now on, he added, “it comes down to distinguishing what’s what, the quality.”

—Rob Sharp

“Park Seo-Bo: Ecriture 1967-1981” is on view at White Cube Mason’s Yard, London, Jan. 15–Mar. 12, 2016.

“Dansaekhwa and Minimalism” is on view at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Jan. 16–Mar. 12, 2016.

“When Process Becomes Form: Dansaekhwa and Korean abstraction in the 1970's and 1980's” is on view at The Boghossian Foundation, Brussels, Feb. 20–April 24, 2016.

Chun Chang-Sup is on view at Kukje Gallery, Seoul, Feb. 26–Mar. 27, 2016.

“Park Seo-Bo: Ecriture 1967-1981” is on view at White Cube Mason’s Yard, London, Jan. 15–Mar. 12, 2016.

“Dansaekhwa and Minimalism” is on view at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Jan. 16–Mar. 12, 2016.

“When Process Becomes Form: Dansaekhwa and Korean abstraction in the 1970's and 1980's” is on view at The Boghossian Foundation, Brussels, Feb. 20–April 24, 2016.

Chun Chang-Sup is on view at Kukje Gallery, Seoul, Feb. 26–Mar. 27, 2016.