With the weather getting warmer and the days longer, it’s road-trip season. We’ve put together a list of public sculptures—some are beloved, some more infamous, and a few are off the beaten path—that all make great pit stops, if not worthy destinations in their own right. From the Lightning Fields in New Mexico to a drinking fountain in the Dallas County Records Building, these ten public artworks make for a geographically illogical but art-historically significant road trip! Seatbelts!

New York City—Sophie Calle,

Here Lie The Secrets of the Visitors of Green-Wood Cemetry

In New York City, there’s an almost never-ending list of places to see great art, but let’s focus on one of the newest additions to the city’s landscape. For

Creative Time’s latest commission

Here Lie the Secrets of the Visitors of Green-Wood Cemetery (2017-2042), French conceptual artist

Sophie Calle designed a marble obelisk gravestone with a mail slot-like opening at its base. Visitors are asked to write their deepest secrets on a piece of paper and slip it into the depository for Calle to later collect and ceremoniously cremate.

Here Lie the Secrets is a good beginning to any trip where you can unload some emotional baggage before over-packing your actual luggage.

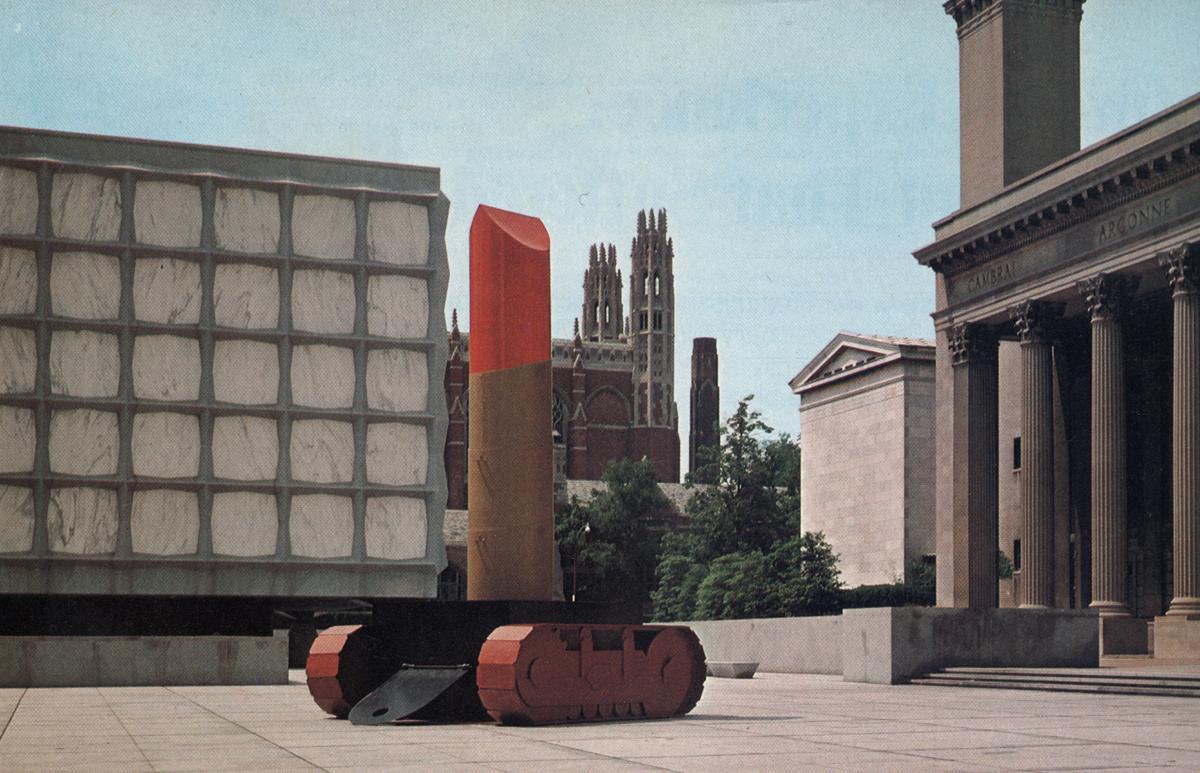

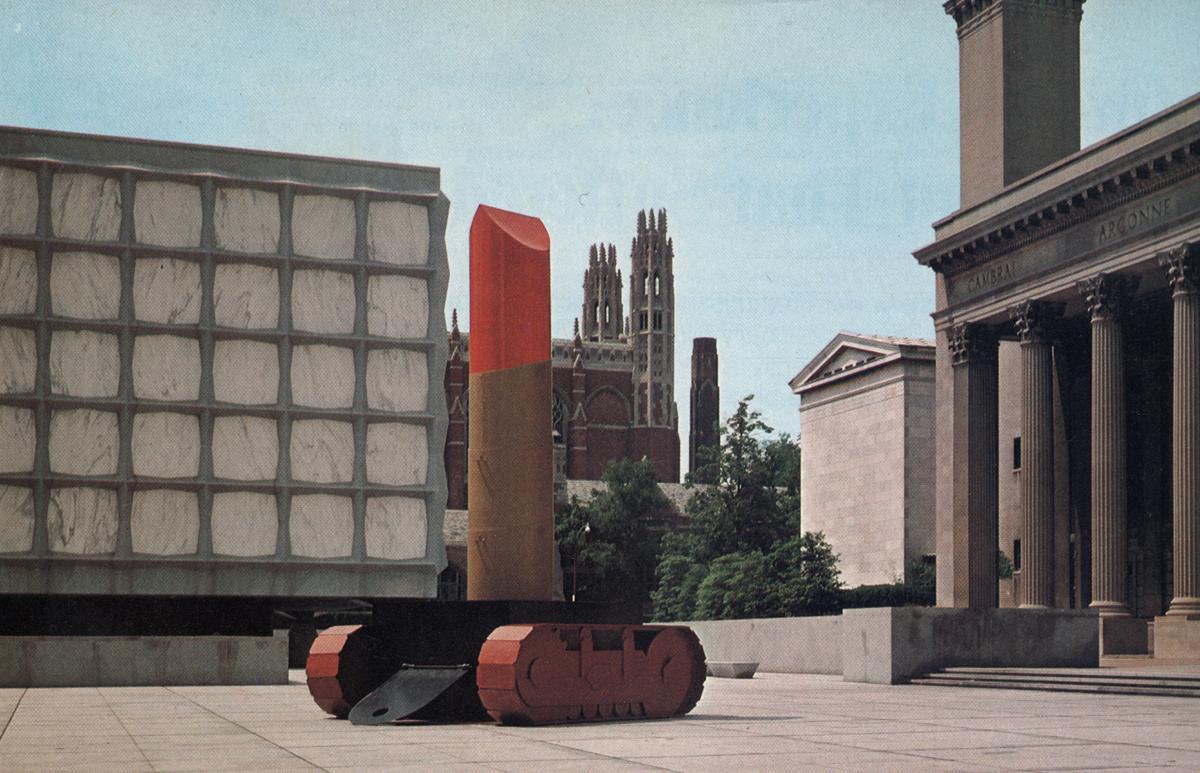

After unburdening your soul, head over to Yale University and see

Claes Oldenburg’s

Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks (1969, 1974). Unlike most public sculptures,

Lipstick was not commissioned by a municipal government or a well-funded nonprofit. Instead Oldenburg collaborated with architecture students at Yale in 1969 to create a Vietnam War protest monument that could also serve as an eye-catching meeting point and soapbox-like platform for protestors and speakers. The 24-foot-high sculpture was placed in Beinecke Plaza, right outside the university president’s window. In typical Oldenburg fashion, the sculpture featured an outrageously large tube of lipstick, with sensuous curves and a glossy sheen, affixed to a brown and black military tank. Originally, the lipstick’s tip inflated and deflated, a visual gag that emphasized the monument’s inherent eroticism, but that quickly malfunctioned. Months after its initial installation, Oldenburg removed the sculpture from the plaza in order to refashion it out of metal. In 1974 it was re-presented to Yale; today, it permanently resides in the Morse College Courtyard.

On your south-bound way down the east coast, be sure to slow your roll in Atlanta, Georgia—drive too fast and you might miss

Sol LeWitt’s

54 Columns. The concrete columns, ranging from 10 to 20 feet high, speak to LeWitt’s devotion to

Minimalism and abstractly reference Atlanta’s metropolitan skyline. But unfortunately, the reference may have been a bit

too abstract: The columns were erected on a piece of donated land in the middle of a residential neighborhood, leading many to assume that the columns were supports for a forthcoming apartment building. LeWitt’s pieceis an example of site-specificity gone wrong, a grand monument somehow made invisible. What a perfect opportunity for a picnic in between the pillars and to discuss the flaws of modernist public sculpture!

Next up, the Windy City. If you’ve ever looked at Instagram for more than 60 seconds you’ve probably seen the Bean (by

Anish Kapoor) more than enough. Instead, veer a few blocks west to check out

Pablo Picasso’s untitled sculpture in Daley Plaza. Now a famous landmark, the piece was initially met with skepticism from Chicagoans. Many lambasted the fact that the piece, and Picasso, had no significant ties to Chicago culture. And it didn’t help that Picasso’s cubist style rendered his subject matter unrecognizable, causing even more confusion and outcry. When Mayor Richard Daley unveiled the massive steel sculpture in 1967, he hoped that the public would view it with, “the belief that what is strange to us today will be familiar tomorrow.” Daley’s wish came true, as the “Chicago Picasso” is now a beloved landmark and main attraction for out-of-towners. This summer, the city celebrates the 50

thanniversary of the piece with a special commemoration ceremony. While you’re there, try to sculpt a replica of the piece using just some crackers and your chisel-teeth!

Minneapolis, MN—Minneapolis Sculpture Garden

The Minneapolis Sculpture Garden has been closed for almost two years for extensive renovation but is set to reopen this June—perfect timing! Once construction is complete, new commissions from

Nairy Baghramian,

Theaster Gates, Phillippe Parreno, and others will join landmark works like

Oldeburg and Van Bruggen’s

Spoonbridge and Cherry and

Jenny Holzer’s

Selections from the Living Series. When you’re done traversing the sculpture trails, check out the garden’s artist-designed mini-golf course and squeeze in a quick round.

It’s only a few more hours to Kansas City, Missouri, where you can see

Louise Bourgeois’s 11-foot tall

Spider (1996). Installed in the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art’s courtyard, the sculpture looks almost like it’s wandering through the grassy knoll. The artist chose to depict a spider because, to her, it represents a “feminine hero figure” in that it weaves intricate and beautiful webs and then waits with an astounding amount of patience for their prey. Bourgeois fashioned a few of these large-scale arachnids as a tribute to her mother, who she viewed as equally patient and graceful. (Don’t let this give you any Mother’s Day present ideas!) Follow the direction of the spider’s lean and you’ll find her spider child, a smaller, cuter sculpture “climbing” up the side of the museum. Afterwards, head over to the sculpture garden at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, to see another famous Oldenburg and van Bruggen collaboration,

Shuttlecocks (1994).

Dallas, TX—Lauren Woods, Drinking Fountain #1

There’s plenty of notable and monumental public art in Texas—from

Elmgreen & Dragset’s

Prada Marfa to Henry Moore’s

Three Forms Vertebrae (the Dallas Piece). Even in Texas, though, bigger isn’t always better as Lauren Woods proves with

Drinking Fountain #1 (2013). Tucked away on the first floor of the Dallas County Records Building, a Jim Crow-era “Whites Only” water fountain has been fashioned into a multimedia piece for the public. Pressing the buttons on the fountain’s side triggers a 15-second video montage of protests from the Civil Rights era, the expected stream of water coming after the video ends. Woods’ sculptural intervention facilitates a meditative moment and a new way to approach historical signifiers of America’s troubling past—in a more visceral way than an explanatory plaque could ever provide. Take a moment to refill your reusable water bottle—the bigger the bottle the more time you’ll have with the piece.

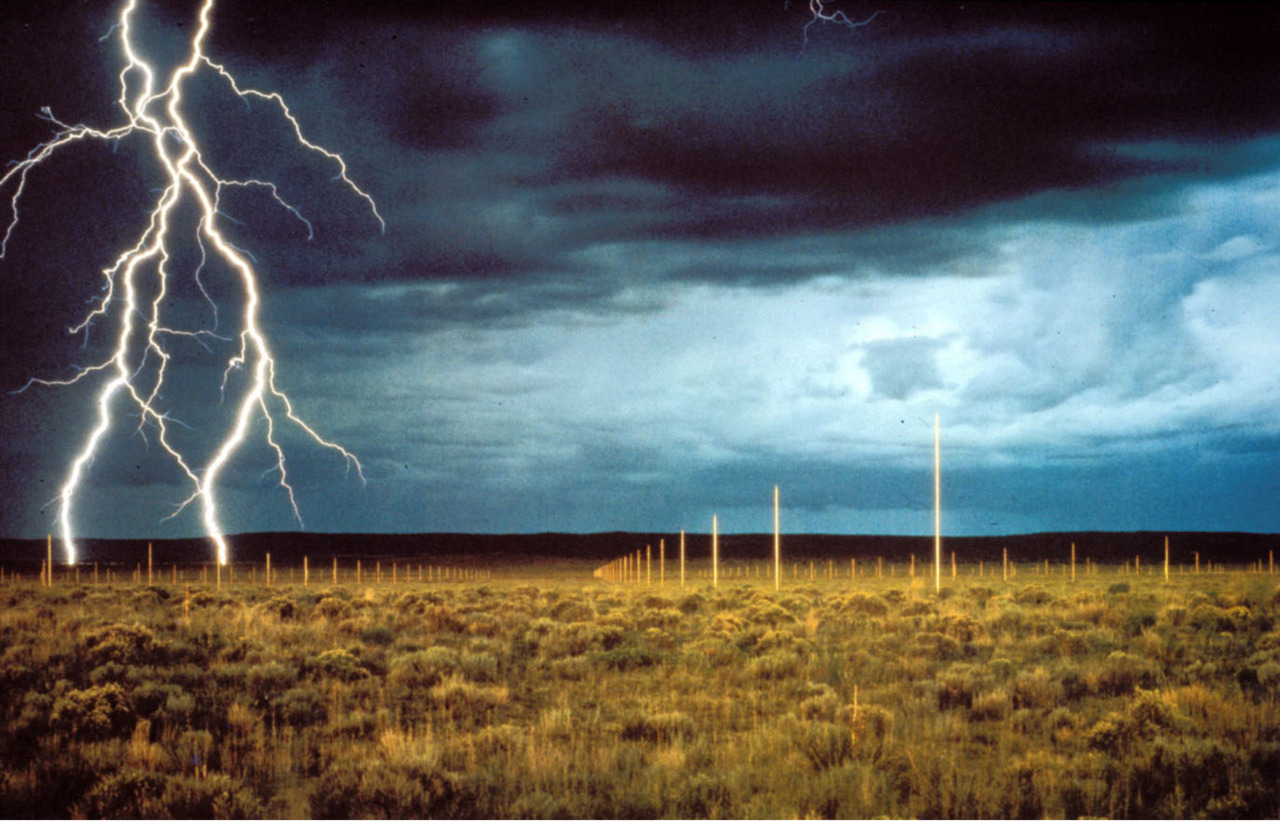

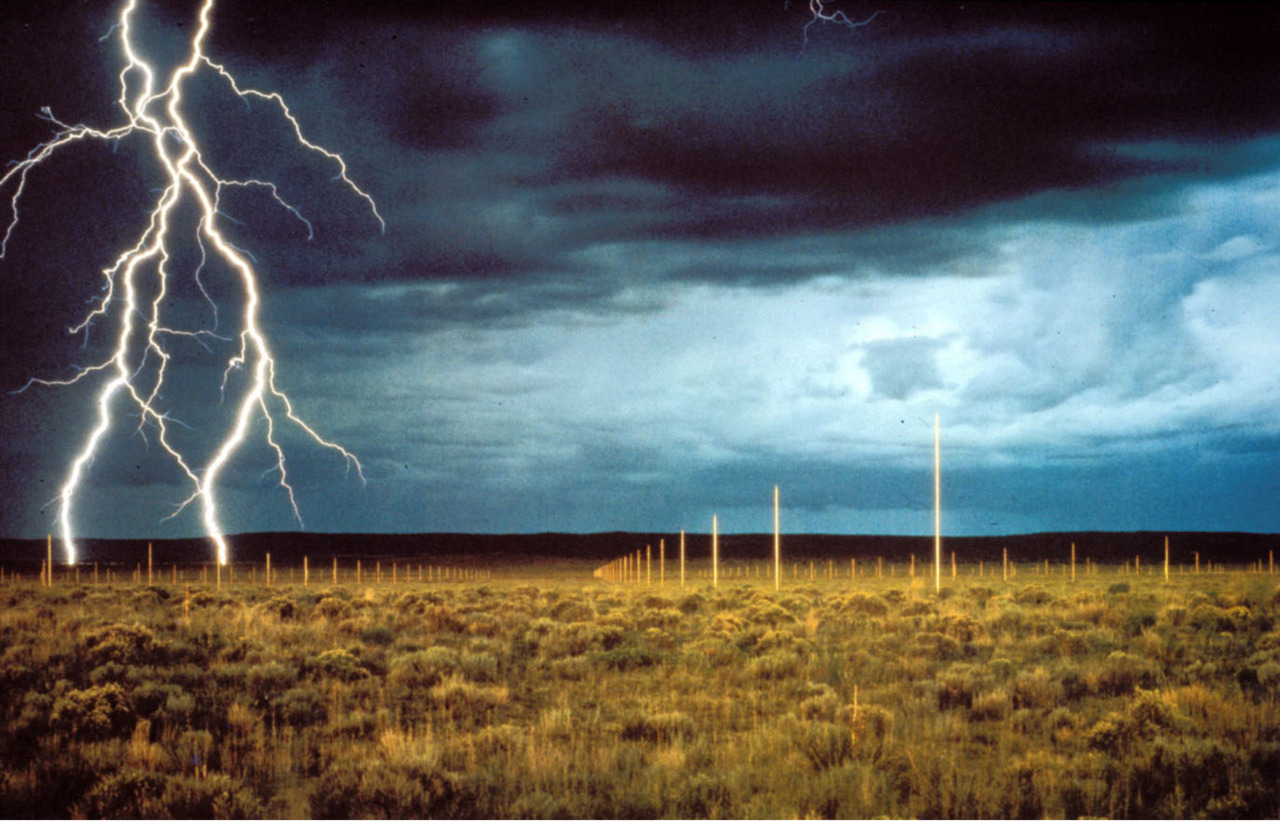

Most of the works on this list are best viewed during the daytime, but Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field (1977) is perfect for an overnight reprieve. De Maria was often associated with the land art movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s, wherein artists sought to protest the commercialization of art objects by crafting site-specific works in under-populated areas of the country, often made with naturally occurring materials. The Lightning Field is located on a desolate stretch of land in western New Mexico, its exact location kept well hidden from the wider public. The piece consists of 400 steel poles with pointed tips arranged in a mile-by-kilometer grid formation, and are meant to attract bolts of lightning during the influx of late summer storms. Dia Art Foundation, the work’s owner, offers a shuttle to a small cabin on the grounds in order to facilitate a camping-like experience, allowing visitors to spend hours with Lightning Field and view the work at its most magnificent times—sunrise and sunset. But know that reservations must be made ahead of time, and are often booked a year in advance.

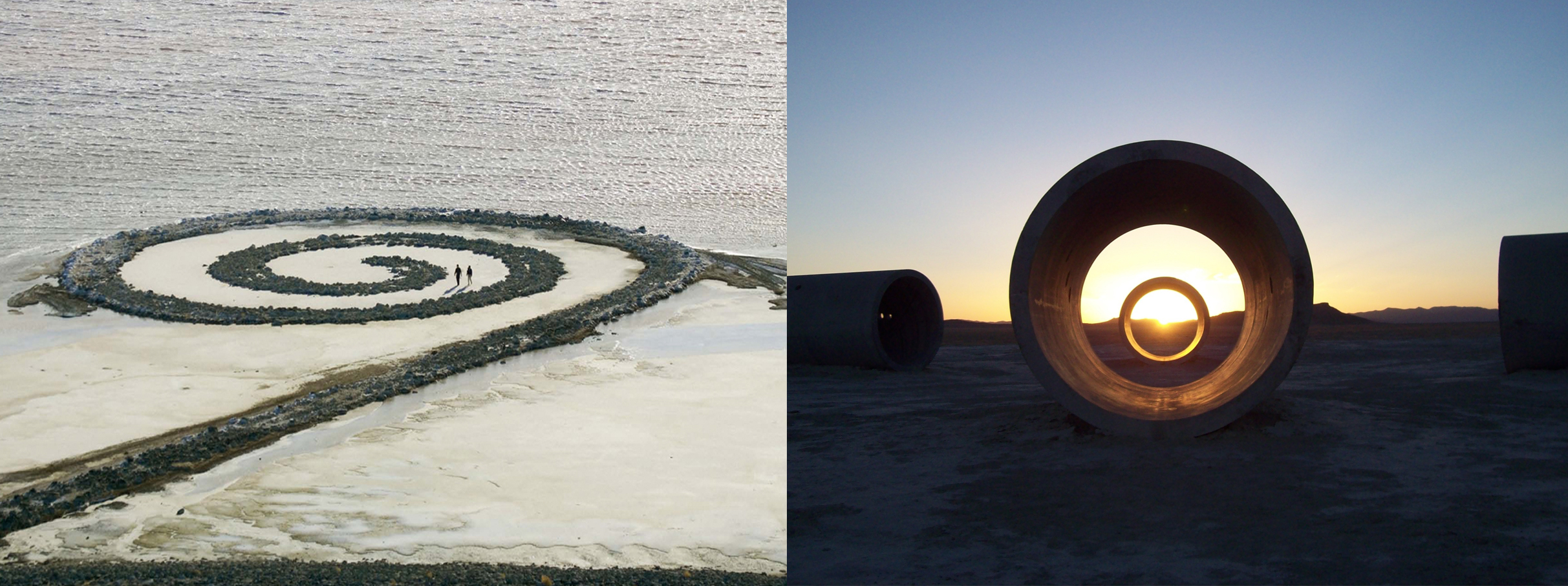

Spending the day in northern Utah, we can see two legendary, beautiful public works in one fell swoop: Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) and Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1973-1976). Smithson and Holt were husband-and-wife pioneers of land art. (Smithson particularly inspired many with his theoretical writings about the new movement.) While it may seem cliché to mention these two works in the list, they are breathtaking in person and absolutely worth the drive. Just make sure to bring a full tank of gas, and check your preconceived notions at the door.

San Diego, CA—Nancy Rubins, Pleasure Point

We’ll end our cross-country road trip in San Diego, California. Even though the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego La Jolla branch is closed for renovation, we can still see Nancy Rubins’ Pleasure Point (2006) from the shores of La Jolla beach. Rubins is known for large, chaotic sculptures made from a plethora of discarded machinery, from household appliances to airplane parts. For Pleasure Point, she assembled a gaggle of maritime vessels and bound them together with steel and wire but without interior supports. Resembling an unpolished crystal or a monstrous stalactite, the sculpture looks as if it crashed through the Museum’s façade without warning. Pleasure Point, like many of Rubin’s works, provokes the viewer to think about obsolescence, or more simply, how industrial junk can be transformed into another’s awe-inspiring treasure. Well, now you’re on the beach—so relax, say ‘hey’ to the sea lions, and pat yourself on the back for completing the most epic (and geographically illogical) art historical road trip ever.

BUY THE WORLD'S BEST CONTEMPORARY ART. ONLINE.