A first look at Serpentine Pavilion 2024: ‘It really is an archipelago’

The Serpentine Pavilion 2024 opens its doors and we catch up with its architect, Minsuk Cho of Mass Studies, to talk about the design’s origins, concept and future travels

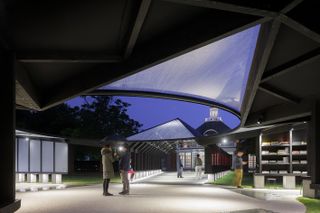

The Serpentine Pavilion 2024 is titled ‘Archipelagic Void’ – a name that perhaps at first glance does not instantly bring a park installation to mind. Yet, as its author, Korean architect Minsuk Cho, the principal of Seoul studio Mass Studies, explains, it's a particularly purposeful description. The term ‘archipelago‘ is used ‘to bring together an amalgamation of cultures, and from it, something completely unexpected comes out’, says Cho. ‘It's not hybridisation. It's a great model for our globalised era.’

Now completed in London's Kensington Gardens, the large-scale installation is about to open to the public (accessible from 7 June 2024). This is the 23rd pavilion in the Serpentine Galleries' much-loved series. As always, it will be accompanied by a curated season of events, such as a newly commissioned soundscape by composer Jang Young-Gyu; The Library of Unread Books, a piece by artist Heman Chong and archivist Renée Staal; and a series of performances and talks. It's all part of a carefully composed, rich programme of concepts and activities, with Cho's architectural pavilion design at its heart.

Minsuk Cho of Mass Studies

Serpentine Pavilion 2024: utopian and meditative

At the core of Cho’s concept sits the idea of ‘bridging’ or combining, putting things (physical elements, cultural ideas) together. ‘In Korea, and perhaps other Asian cultures, the idea of the pavilion is about a simple, often wooden structure, placed among amazing surroundings, and its role is to be a humble, private, meditative space. It is more about observing,' he explains. ‘In the West, the pavilion is often seen as a folly, something otherworldly and almost utopian.’

His (self-imposed) task, realised through the 2024 Serpentine Pavilion commission, was to mix these two ideas of what a pavilion can be and surround them with different functions, creating a menu of activities for the visitor, as well as the option to flexibly adapt the space to potential new uses. This thinking led to a structure consisting of five 'islands' – they form the project's ‘archipelago’ – a concept also manifested in the idea of bringing the two different interpretations of a pavilion into a single piece.

'The word “archipelago” came from a book Hans [Ulrich Obrist, the Serpentine Galleries’ artistic director] was making with Édouard Glissant [The Archipelago Conversations]. They coined the [use of] “archipelago” as a way to generate this cultural diversity,’ Cho recalls, talking about what inspired the pavilion's name.

'I wasn’t thinking about it as [an archipelago] as I was initially designing it, but two days before submitting the proposal, I came across the book and thought, that’s exactly what we’ve been doing!'

Serpentine Pavilion 2024 designed by Minsuk Cho, Mass Studies. Design render, view of void from the Gallery and Play Tower

The Archipelagic Void’s five ‘islands’

An open-air area in the middle of the structure offers space for contemplation in the shape of a circular 'void' that nods to the madang, a small, flexible courtyard found in old Korean houses and used for anything from household chores to family celebrations and ceremonies. The broken-down volume of this year's pavilion was also informed by its surroundings and temporary nature, and was conceived to help it blend with its leafy, low-rise context.

Each of the 'islands' is designed to have its own function and purpose. The 'Gallery' is a welcoming main entry, 'extending Serpentine South’s curatorial activities outside'. The 'Auditorium' becomes an informal, gathering area for events and impromptu meetings. The 'Library' is one of the smallest areas and offers 'a moment of pause'. The 'Tea House' references Serpentine South's historical role as a tea pavilion. And the 'Play Tower' is the home of a multifunctional, netted structure for kids (and adults) to play in.

Cho worked on his pavilion's floor plan vigorously. 'Looking at the previous pavilions, 22 before us, each brought a different way [for the public] to be in a generous space of different shapes. I am an architect and think in floor plans. In my practice, I have designed pavilions in the past, so we thought, what about we empty the place we use together the most, and we create an 8m void there instead?' he explains.

Serpentine Pavilion 2024 designed by Minsuk Cho, Mass Studies. Design render, exterior view

'We looked at ways of bringing people together. It's about being generous and offering choices. So there are these different experiences around it and this empty space in the middle – the most flexible space, it can be whatever you want. Like a Korean madang.'

An additional bonus of the loosely star-shaped layout of the pavilion is that it creates a variety of outdoor areas in-between the irregularly shaped, built sections – more open-ended public space for visitors and users to make their own.

The result is a structure placed on a concrete base that not only negotiates the site's slope with flair (supporting the pavilion's upper level, it becomes a bench, a perch or a table at different parts of the building's body); it also connects to the existing concrete foundations on site, ensuring it reuses what's there and no significant new groundwork was needed.

The top is made of timber (Douglas fir, sourced locally) and recyclable PVC panels that add playful translucency and a punch of colour. Keeping things environmentally friendly was important to Cho and his practice. The material selection also makes the whole soft and tactile – another important quality for the team.

Adding to its sustainable architecture credentials, the structure can also be disassembled to travel in future. Its five sections' relatively simple, modular nature means they can be reconnected in a variety of ways. The architect adds: 'We calculated that taking down the elements that make the pavilion and reconnecting them in different configurations offers the possibility of creating, upon reassemblage, 180 new, different pavilions.'

There’s something poetic about his thinking – a bridging of cultures, a coming together – matched with efficiency and careful spatial planning that makes the most of the brief and maximises it. Combining invention and discovery, East and West, the 2024 Serpentine Pavilion is about to open.

The Serpentine Pavilion 2024 will be open to the public 7 June – 27 October 2024

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture & Environment Director at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020) and House London (2022).

No comments:

Post a Comment