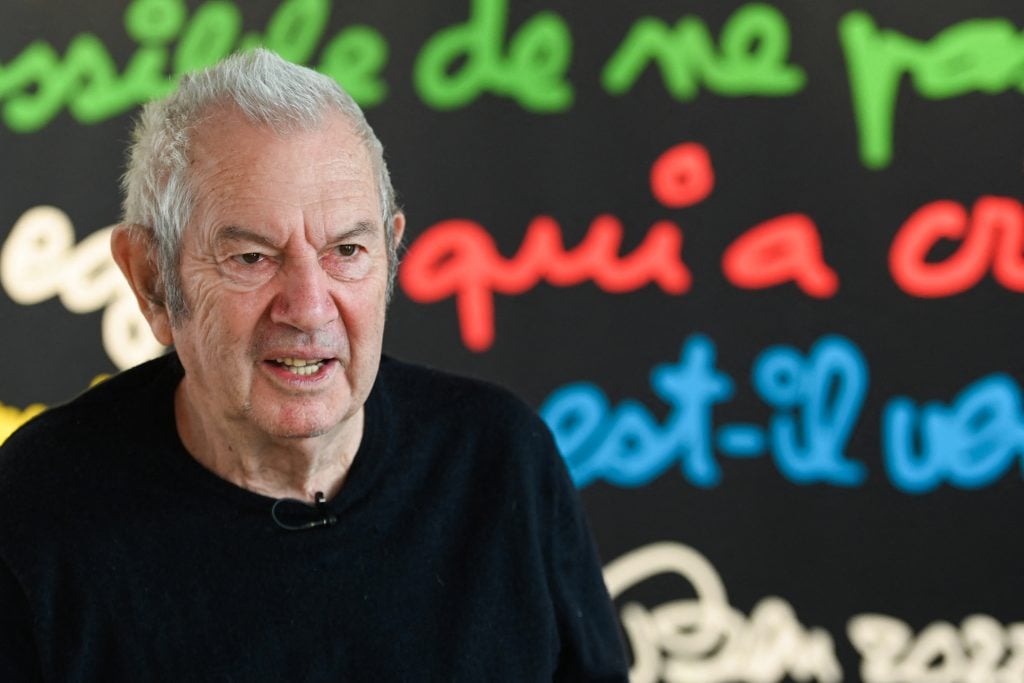

BEN VAUTIER (1935–2024)

Self-taught French artist and provocateur Ben Vautier, a cofounder of the Fluxus movement known for his humorous text-based paintings, took his own life June 5 at his home in Saint-Pancrace, France, hours after his wife, Annie, died of a stroke. Vautier—who frequently went by the mononym Ben—was eighty-eight. The couple’s children, Eva and Francois, confirmed his death. Beginning in the 1950s, Ben was a vocal proponent of the idea that “everything is art,” not only incorporating the phrase into many of his works (tout est art), but embracing life itself as inseparable from art. Indeed, his text works, often scrawled in white paint on a black background, wormed their way into the national consciousness of France, if not the world. “On our children’s pencil cases, on so many everyday objects and even in our imaginations, Ben had left his mark, made of freedom and poetry, of apparent lightness and overwhelming depth,” said French president Emmanuel Macron in a statement addressing the artist’s death.

Ben Vautier was born in Naples in 1935, the great-grandson of renowned Swiss genre painter Benjamin Vautier (1829–1898). His parents divorced when he was young, and he spent an itinerant childhood with his mother, living in Turkey, Egypt, and Switzerland before finally settling in Nice, near his mother’s native Antibes. “I was very sad because my father went away with my brother who was one year older than me, and I was separated from my brother,” he told Forbes’s Y-Jean Mun-Delsalle in 2023. “I think I must have been traumatized because I made a kind of wall. . . . I never talk about my childhood.”

A poor student, Ben was removed from school by his mother and put to work in a bookshop, Le Nain Bleu, where he discovered art within the pages of the volumes intended for sale. Drawn to the abstractions of Picasso, Serge Poliakoff, and Pierre Soulages, he cut out the pictures he liked best and tacked them to the wall of the attic in which he was then living, hoping no one would notice. Before he was twenty, he had embraced the concept that “art must be new”: The sentiment would soon align him with the Fluxus movement.

In 1958, Ben opened a record store in Nice called Laboratory 32 (Le Magasin), which he would run through 1973; in its top floor, a space so tiny that visitors couldn’t even stand up in it, he opened a gallery called Galerie Ben Doute de Tout. Through the shop and gallery, which together functioned as a kind of salon, he met Yves Klein and gained an interest in Nouveau Réalisme; he also met Fluxus cofounder George Maciunas, who introduced him to the work of French dadaist Marcel Duchamp and the music of John Cage, both of which proved of shattering importance to Ben.

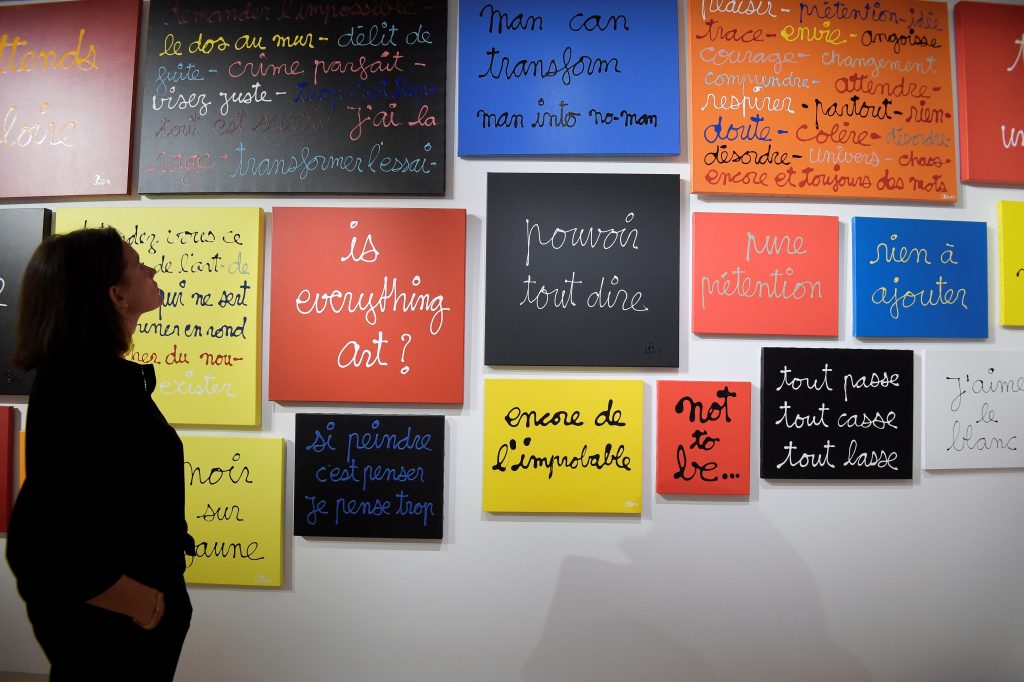

His wide-ranging practice would soon encompass mail art; performances, which he called “Gestes” and which were frequently crude in nature; and the black-and-white cursive word paintings for which he became most widely known. Many of these celebrated life, while still others queried the human condition or took aim at the egotism of artists (from which he himself was not immune). All were intended to provoke thought; some were meant to spark fights. His text works in particular anticipated the work of artists such as Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, and Richard Prince. “Vautier,” wrote Bary Schwabsky in a 1999 issue of Artforum, “is an artist of relentless volubility.”

Characteristic of Ben’s irreverent nature were works such as boxed editions of God; wineglasses in limited editions of twenty, accompanied by certificates verifying that he had drunk the contents in sequence; Flux missing card deck, 1966, a deck of playing cards from which he had removed the ace of spades; and so-called appropriation works, found objects that he branded art by writing on them Ben, je signe (I, Ben, sign). His KUNST IST ÜBERFLÜSSIG (Art is Superfluous), 1972, took the form of a banner proclaiming the titular sentiment, strung provocatively across the top of the Fridericianum in Kassel at Harald Szeemann’s Documenta 5. As Ben had intended, his work leaked outside the walls of the museum, becoming enmeshed in the fabric of everyday life, as embodied for example by his Le Mur des Mots (The Wall of Words), 1995, a group of plaques bearing brief texts relating to art, life, and philosophy and covering a 100-by-40-foot exterior wall of the art school in Blois, France. Too, it lent itself well to reproduction, appearing on the pencil cases referenced by Macron, as well as school bags, notebooks, and the steps of the tramway in Nice.

In recent years, Ben was awarded retrospectives at the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Lyon, France; the Museum Tinguely, Basel; and the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City. His work is held in the collections of major arts institutions around the world, including the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid; and the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. His record shop, which by the end functioned as a kind of evolving sculpture, was reassembled inside the Centre Pompidou, Paris, where it remains today.

artnet

People

Ben Vautier, the Fluxus Provocateur Who Proclaimed ‘Everything Is Art,’ Dies at 88

The French artist's paintings and performances helped usher in a new age of conceptual art.

A leading light of the Nice School of artists and the international Fluxus movement, Ben Vautier, more often known simply as “Ben,” is remembered for his highly experimental conceptual practice that inherited the radical spirit of artists such as John Cage, Duchamp, and the Dadaists. Always driven by the pursuit of novelty, Vautier is best known for surprising audiences with performances that made art out of everyday life and for his unique “écritures,” or written paintings.

“My definition of art is: astound, scandalize, provoke, or be yourself, be new, bring, create,” Vautier said in 2010. From early in his career he proudly proclaimed “everything is art.”

At the age of 88, Vautier died by suicide on June 5 at his home in Nice, France, just hours after the death of his wife Annie Baricalla who had suffered a stroke two days earlier. A statement issued by the couple’s children Eva and Francois said he had been “unwilling and unable to live without her” after 60 years of marriage.

Benjamin Vautier was born in Naples on July 18, 1935 to an Irish and Occitan mother and a French-Swiss father; his paternal grandfather was the Swiss painter Marc Louis Benjamin Vautier. His childhood was spent moving between several countries, including Turkey and Egypt, during the war, before settling in Nice in 1949. Vautier would remain there for the rest of his life.

Installation view of retrospective for French artist Benjamin Vautier, also known as Ben, at the Musée Maillol in Paris in 2016. Photo: Bertrand Guay/AFP via Getty Images.

Towards the end of the 1950s, Vautier set up Laboratory 32, a shop selling second-hand records that he kept until 1973. It became a regular meeting place and exhibition space for a community of local artists including Yves Klein, Martial Raysse, Bernar Venet, and Sarkis. At Klein’s encouragement, Vautier began writing all over the walls of the shop, a precursor to his later “écritures” paintings, made by applying white acrylic paint straight from the tube onto a dark ground. The short, simple but irreverent slogans eventually became recognizable throughout France, even adorning pencil cases.

“In my writing, it’s not the aestheticism that matters, otherwise I’d take more care over it,” Vautier once explained. “Generally, I write to be read and understood. It’s the meaning that has to come across.”

In the late 1950s, Vautier also began his “Living Sculptures” series, produced by signing his name on found objects, friends, and even passersby from the street. By 1963, the artist had even signed the entire city of Nice and manufactured certificates of authenticity for the artwork. These actions tested the limits of what could be considered art and what kind of intervention is necessary to assert authorship over an artistic output.

Performance in which French artist Benjamin “Ben” Vautier is suspended 200m above the ground on his bed in Nice, on July 4, 1985. Photo: Christophe Simon/AFP via Getty Images.

Appropriation would become a particular trademark of Vautier’s after he became a member of the amorphous Fluxus movement in 1962 when he met its founder George Maciunas in London. He invited Maciunas to stage a Fluxus festival in Nice the following year.

Further breaking down the limits between art and real life, Vautier used his own body to stage “gestes,” or happenings. In 1962, he spent two weeks in the window of Gallery One in London. In 1964, he performed Hurler, during which he screamed and yelled until he lost his voice. A record of the performance Vomir consisted of vomit stored in a jar and dated June 8, 1962.

By the 1970s, Vautier had received critical acclaim and institutional recognition in Europe. He participated in Documenta 5 in 1972 and, in 1977, helped organize the influential group exhibition “A propos de Nice,” one of the inaugural shows at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. His work is held in several major public collections, including Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Reina Sofia in Madrid, and the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris.

No comments:

Post a Comment