|

|

What Steve Jobs learned from Buckminster Fuller during their only meeting

The two luminaries met in 1980, and Fuller’s influence on Apple is visible to this day.

On October 24, 1980, a man named Taylor Barcroft drove to San Francisco. He was there to see Buckminster Fuller, the architectural designer and futurist, who was delivering a speech at a wellness conference. After the event, Barcroft headed south with Fuller and a cameraman to Cupertino, where they parked at a building on Bandley Drive. Barcroft had arrived without an appointment, and his entire plan depended on how confidently he handled himself now. Leaving Fuller in the car, he went inside and approached the receptionist. “I’ve got Bucky Fuller here for Steve Jobs.”

The visit was a gamble, but he had reason to believe that it would pay off. Barcroft, a University of Denver graduate in his early 30s, hoped to produce a series of cable television programs featuring commentary from Fuller. A segment with one of the founders of Apple Computer would be a compelling proof of concept, but instead of calling ahead, Barcroft thought he would have better luck by showing up unexpectedly with his famous guest. “I knew Steve was a fan of Bucky,” Barcroft remembered. “Anybody like Steve would be a fan of Bucky. And I wanted Bucky to meet Steve, who was going to fulfill Bucky’s dream.”

It was a risky move, but it succeeded. After the receptionist passed along his message, the first person who emerged to greet Barcroft was Mike Markkula, the chairman of the company, who spoke with him for a minute as they waited for Jobs to appear. Word also reached Daniel Kottke, a mellow but bright 26-year-old who had met Jobs nearly a decade earlier when they were freshmen at Reed College in Oregon. He had become close to Jobs, with whom he later shared a house, and was hired as the twelfth official employee of Apple.

Kottke was at his lab bench, which stood in a work area of cubicles and Herman Miller chairs, when someone announced that they had a visitor: “Buckminster Fuller’s here.” He rose immediately and hurried for the lobby, where he saw a cluster of people standing outside. His eyes were drawn at once to two men. One was Jobs, who wore his usual outfit of a casual shirt and jeans, and the other was R. Buckminster Fuller, whose face in those days was familiar across the world.

Fuller, 85, was dressed in the dark suit that he favored for all of his public appearances, and, in person, he was startlingly small. His driver’s license may have said that he was five foot six, but he had been about two inches shorter even in his youth, and his stature had been diminished by age. He had a huge, bald head with white hair trimmed almost to the scalp, a large hearing aid, and black, plastic glasses that magnified his hazel eyes into soft, enormously deep pools.

Joining the circle, Kottke spoke briefly with Fuller, whose work he had admired since high school. Kottke expected to talk to him further—he was often the one who showed guests around the office—but as the group headed off without him, he realized that Jobs wanted Fuller to himself.

As for Barcroft, he couldn’t believe his luck. He ended up at a conference table with Fuller and Jobs, who exchanged a few words while a cameraman recorded the meeting. When it was time for a tour, however, Barcroft was left behind as well. Jobs clearly didn’t want to include anyone else, and no one would ever know what he and Fuller said to each other in private at Apple, which was only months away from its initial public offering.

Afterward, Barcroft took Fuller back to his hotel. Barcroft was elated, but his plan for a cable show never materialized, and he later lost the footage of Fuller and Jobs. For his part, Fuller was unconvinced that the personal computer would enable his lifelong vision of access to information. “He didn’t believe it,” Barcroft recalled. “He thought that only mainframes could do that work.” Fuller had devoted his career to predicting the impact of technology, but he saw nothing special in Apple: “I remember him saying that he thought the computer was a toy.”

Judging from his eagerness to meet Fuller, their encounter left a greater impression on Steve Jobs, which came as little surprise to Daniel Kottke. “In my early friendship with Steve, he was interested in so many things that I was also interested in,” Kottke said. “That definitely included Fuller.” Since the ’60s, college campuses had found an unlikely hero in Fuller, whose reputation as an inventor was based on the geodesic dome, a hemispherical structure used in everything from industrial buildings to hippie communes, as well as the sculpture studio at Reed. He had been given a crucial push by the Whole Earth Catalog, an oversized guide to books and tools for the counterculture that Jobs, who avidly read it in college with Kottke, described as “one of the bibles of my generation.”

And Fuller’s influence at Apple was visible in even more fundamental ways. When Jobs and his partner Steve Wozniak—who later praised Fuller as “the 20th-century’s Leonardo da Vinci”—needed an industrial designer to build the housing for the Apple II, they hired Jerry Manock, a graduate of the legendary product design program at Stanford University. Manock established what became the Apple Industrial Design Group using an iterative approach that he attributed to Fuller: “He wasn’t interested in solving just one tiny design problem. He would look at the next level up, and the next level up, and the next level up.”

A year after his visit to Cupertino, Fuller received an Apple II as a gift, and his connection to the company resulted in one last tribute during his lifetime. Wozniak had spent millions on the U.S. Festival in San Bernardino, which he conceived as a Woodstock for his generation, “but maybe better.” On May 30, 1983, the crowd was treated to an elaborate video introduction to Fuller’s philosophy, which hundreds of thousands of concertgoers watched on an enormous screen before Stevie Nicks took the stage to sing “Dreams.”

Fuller died a month later, a half year before the release of the Macintosh, but his legacy at Apple endured. On September 28, 1997, a television commercial debuted during the network premiere of the animated film Toy Story. Steve Jobs had recently returned in triumph to Apple, and over a montage of luminaries—from Martin Luther King Jr. to Pablo Picasso—the actor Richard Dreyfuss offered a declaration of principles: “Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently.”

The “Think Different” campaign was meant to sell computers, but it also spoke to an authentic vision personified by Fuller, who thought differently—for better or worse—than just about anyone else. “You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify, or vilify them,” Dreyfuss concluded. “About the only thing you can’t do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward. And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.”

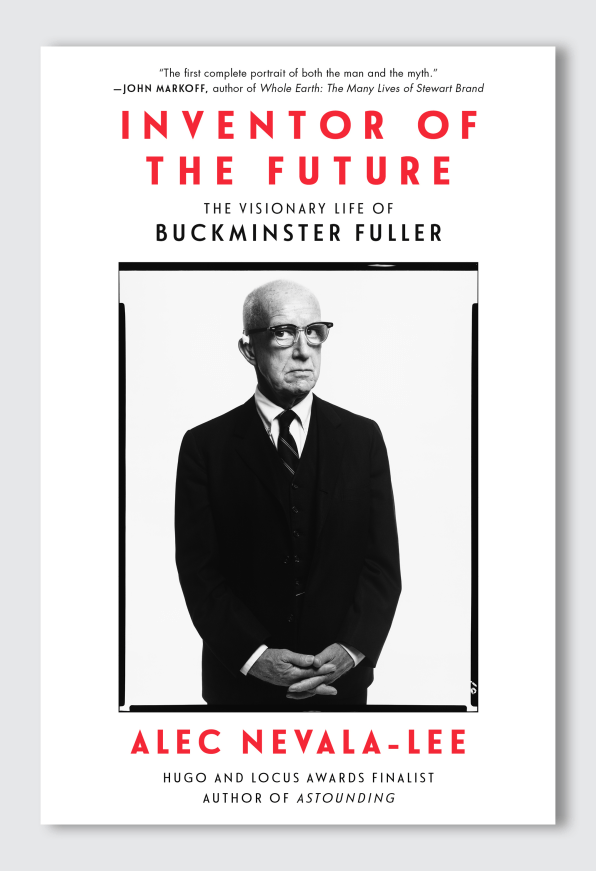

Adapted from Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller by Alec Nevala-Lee. Copyright © 2022 Alec Nevala-Lee. Reprinted with permission from Dey Street Books, HarperCollins Publishers.

No comments:

Post a Comment