COLLECTING 101

The Evolution of Art, Part II: From Minimalism Until Now

Image via Sors Paris.

How did we get to where we are today in the realm of fine art? Who were the artists that changed the course of art history and what were the artworks that broke the mold? In Part I of this two-part series we described the advances in Modern art starting with the advent of abstraction and ending with Donald Judd and the Minimalists, showing the progression of art from 1915 to 1969. But what happened next? Here we introduce some of the more recent developments leading up to art today, starting with feminist art in the ‘70s and ending with new media art.

(To see movements one through five, read The Evolution of Art: Artworks That Advanced Our Understanding of the Medium, Part I.)

6. Feminist Art

JUDY CHICAGO

The Dinner Party (1974 - 1979)

JUDY CHICAGO

The Dinner Party (1974 - 1979)

Like most major institutions, the Western art world has been dominated almost exclusively by male histories and narratives, often diminishing the artistic contributions of women to the craft. American artist Judy Chicago saw a pressing need to correct that history. Coining the term "Feminist Art" in the 1970s, Chicago sought to end the "ongoing cycle of omission in which women were written out of the historical record." As part of that initiative, Chicago co-founded the Womanhouse project along with fellow feminist artist Miriam Schapiro in 1971 (the two also co-founded the CalArt’s Feminist Art Program). The ambitious project, involving a large house in which each room was transformed into a installation or a backdrop for performance, became the first feminist art project to receive national attention, introducing the movement to the general public and generating the fundamental dialogues and practices that spurred the creation of works such as The Dinner Party.

Arguably the opus of the First Wave Feminist Art movement, The Dinner Party is a monumental installation that literally gives women their long-due seat at the table. This celebration of women is, according to Chicago, “a reinterpretation of The Last Supper from the point of view of women, who, throughout history, have prepared the meals and set the table." Now on permanent exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, the work features a massive 48-foot triangular table with 39 individual place settings, each one honoring a specific woman in Western history. Every place setting has its own runner, embroidered with the name of the woman whose place it reserves along with illustrations of her accomplishments. Glass plates featuring floral or butterfly-like sculptures symbolizing the vulva also grace each place setting, along with a goblet and cutlery. The floor of the installation is inscribed with the names of an additional 999 remarkable women while the walls pay homage to the 129 collaborators who helped bring the work into fruition. This collaboration with artists working in historically feminine mediums (such as textile, china painting, and glass) highlights the frequently suppressive, patriarchal distinction between high art versus craft and encourages a feminist practice that is both inclusive and uplifting.

RELATED ARTISTS: Yoko Ono, Barbara Kruger, Carolee Schneemann, Hannah Wilke, Miriam Schapiro

RELATED ARTICLE: A Short Introduction to Feminist Art

RELATED ARTICLE: A Short Introduction to Feminist Art

7. Performance Art

MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ

MARINA ABRAMOVIĆ

Rhythm (1974)

In a 2009 conversation between actor James Franco and Serbian-American artist Marina Abromović (while they make almond sweets covered in gold, a process that Abromović insists is a meditation), the artist lambasts the studio practice. Over a bowl of soaking almonds, she declares, “I hate the studio. Studio is the trap. Studio is the worst place [and] where an artist should never be. Art comes from life, not the studio.” As abstract art became commonplace by the late 1950s, many artists began to turn to performance as the new platform for the avant-garde. They saw their bodies as an artistic medium, one that held the potential to abolish the distance separating artist from audience. Among these artists was Marina Abromović. Performance, for her, became a method of testing the limits of intimacy and trust between artist and audience, as well as the limits of the human body. By creating situations that demanded audience participation, she revealed the artist as a subject, vulnerable to the will of the observer. The experience is one that is visceral and terrifyingly real.

Using her own body as both the subject and material of her work, Abromović created the piece Rhythm 0 in which her body acted as a canvas—a passive surface for whatever her audience decided to do to it. On a table next to her, Abromović placed 72 objects—including a rose, a feather, scissors, honey, a whip and gun loaded with a single bullet—and invited the audience to pick up these objects and manipulate her body at their own will, revealing a side of humanity that, without the confines of social consequences, becomes inherently aggressive and violent. "What I learned was that... if you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you,” said Abromović about Rhythm 0. “I felt really violated: they cut up my clothes, stuck rose thorns in my stomach, one person aimed the gun at my head, and another took it away. It created an aggressive atmosphere. After exactly six hours, as planned, I stood up and started walking toward the audience. Everyone ran away, to escape an actual confrontation."

RELATED ARTISTS: Yves Klein, Vito Acconci, Chris Burden, Yayoi Kusama

RELATED ARTICLE: The Fundamentals of Endurance: Marina Abramović on How She Learned to Refuse the Body's Limits and Make Immortal Art

RELATED ARTICLE: The Fundamentals of Endurance: Marina Abramović on How She Learned to Refuse the Body's Limits and Make Immortal Art

8. '80s Painting / Neo-Expressionism

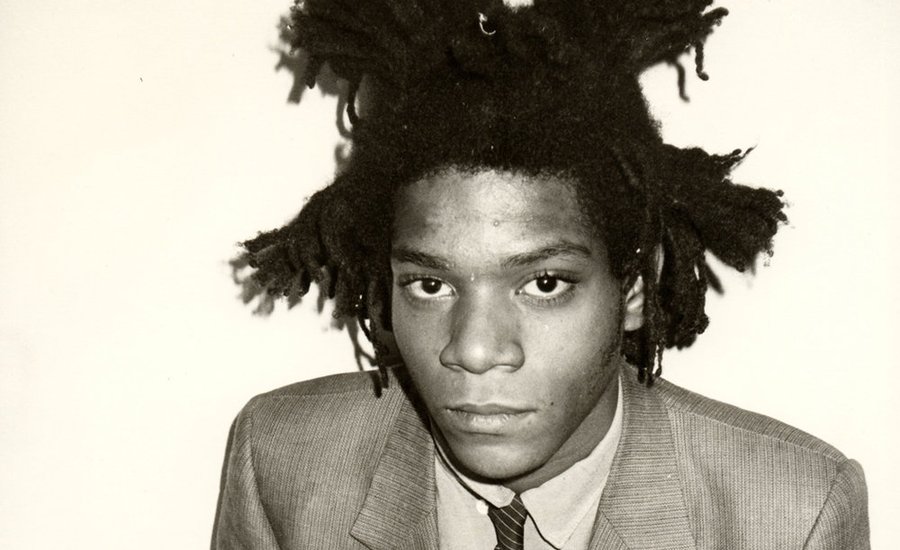

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT

JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT

Untitled (Boxer) (1982)

Famed art critic Roberta Smith described the '80s art scene as a time “when brash met flash,” and this summation could not be more apt. In the 1970s, the art world was in a precarious position; the rise of conceptual and performance art, and its preoccupation with market rebellion, became a liability in its inability to be bought and sold. A wealth of new spaces had opened up in downtown Manhattan and were searching for art that was exciting, trailblazing, and, most of all, marketable. The “flash” of the re-emerging market let to the rise of “brash” painters known as Neo-Expressionists. These artists (like Eric Fischl, David Salle, Elizabeth Murray, Kenny Scharf, Julian Schnabel) ignored critic Clement Greenberg and his prescriptive view of Modernism that had influenced the previous generation of artists, and instead crafted works that combined figurative subjects, abstract landscapes, and intuitive mark-making into volatile works of art. At the same time, graffiti and street art was rising through the cultural ranks, with artists like Keith Haring going from underground troublemaker to Whitney Biennial bigwig.

The breakout star of this decade and movement was, by far, Jean-Michel Basquiat. The son of Afro-Carribean immigrants, Basquiat mixed graffiti aesthetics, rudimentary figures, and Black iconography to create masterpieces that spoke to more than just the art world’s elites. He quickly became friends with some of the decade’s most notable figures, including Andy Warhol. A strong advocate of Basquiat’s work, Warhol later collaborated with him on a series of paintings in the mid-‘80s.

Untitled (Boxer), from 1982, is one of Basquiat’s most potent and powerful paintings. A symbol of excellence, success marked by perseverance, Basquiat’s boxer acts as a hero and an inspiration for the viewer—and for the artist himself. Much like the boxer, Basquiat had to fight many (metaphorical) opponents in the art world to reign supreme; factors like racial oppression, lack of funds, and the struggle to find permanent housing besieged the artist early on. Basquiat’s trademark style is also fully realized in this work—from the background that resembles a graffitied-wall painted over to the simple, mask-like rendering of the boxer’s face.

Buyers rushed to collect Basquiat, spawning a dangerous mix of notoriety and intense pressure that led the artist into a rough battle with depression and drug use. His meteoric rise came to a startling halt in 1988, when Basquiat died of a drug overdose at age 27. His work, however, lives on, resonating with collectors, curators, and art enthusiasts all over the world.

RELATED ARTISTS: Eric Fischl, David Salle, Elizabeth Murray, Kenny Scharf, Julian SchnabelRELATED ARTICLE: Meet the Neo-Expressionists

9. Institutional Critique

ANDREA FRASER

ANDREA FRASER

Official Welcome (c. 2001)

One of art’s most important functions is to critique culture, to make visible seemingly hidden or unintelligible forces and power structures so that we can better understand them—and resist them, if necessary. But art itself—or more specifically, the institutions, economics, and politics that give structure to the art world—is ripe for critique, inundated with the same inequalities and injustices that plague society at large. In the 1990s, performance artist Andrea Fraser popularized institutional critique as an art movement by commenting on the hierarchies, politics, male-dominated history, and commerce that goes on behind the scenes of museums.

In one of her earliest performances (Museum Highlights), the artist posed as a tour guide at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and lead museum-goers on a verbose and theatrical tour of the museum, describing a common a water fountain as “a work of astonishing economy and monumentality” or the museum cafeteria as “regarded as one of the very finest of all American rooms.” In a 2001 performance called Official Welcome, the artist gave a speech at a private reception for the MICA Foundation in which she mimicked “the banal comments and effusive words of praise uttered by presenters and recipients during art-awards ceremonies.” In the middle of the speech the artist began to take off her clothes, striping down to just a thong, bra, and high heels, saying, “I’m not a person today. I’m an object in an art work.” And in 2003, Fraser questioned male power in the art world and the relationship between prostitution and female artistry in her video-recorded performance Untitled. The performance involved having a sexual encounter in a hotel room with a private collector who paid to participate. Five copies of the 60-minute video were produced (one of them is owned by the participating collector.)

Using humor, satire, and perturbation to comment on serious problems that effect the art world at large, Andrea Fraser has helped create a dialogue around systemic issues, paving the way for groups like W.A.G.E. (established in 2008) that advocates for a more equitable distribution of the art world’s economy (i.e. fair wages for artists), and Occupy Museums, an activist group that sprung from the Occupy Wall Street Movement and that made an instillation about artist’s debt at the 2017 Whitney Biennial.

RELATED ARTISTS: Daniel Buren, Hans Haacke, Martha Rosler, Louise Lawler, Fred WilsonRELATED ARTICLES: Arresting Art: How Artists From Robert Gober to Andrea Fraser Have Tackled America's Prisons

10. Video and New Media Art

RYAN TRECARTIN

RYAN TRECARTIN

A Family Finds Entertainment (2004)

From the 1960s onward, artists have been experimenting with video. With more than half of all U.S. homes owning a set by 1955, television became the new proverbial hearth, connecting families and communities with their programming. Alongside this ubiquitous broadcasting medium came the Portapak, a commercial video camera that suddenly allowed just about anyone to create videos cheaply and easily. Artists, of course, could not resist the new medium. Its novelty and accessibility enabled an expanded field of expression, experimentation and documentation that broke away from the tired and restrictive modes of painting and sculpture. This was a wild west of art production. Among the early pioneers of video art was Nam June Paik (largely considered the movement's founding father), who saw video as an anti-establishment tool, capable of empowering the ordinary and democratizing cultural production. That philosophy, along with video’s directness and immediacy, has been foundational in the medium's developments.

Fast forward to the ‘90s and early ‘00s, when an entire generation had been virtually raised on television's high octane, and commercial aesthetics and media manipulation was practically second nature to young artists. In full embrace of this new, inescapable media landscape and vernacular is new media artist Ryan Trecartin. Per the artist, “contemporary art or artists alone have never been a main catalyst for me to want to make art. I’ve been more inspired by how language is used—in culture generally, whether in casual conversation or various forms of media—or by music, TV, dance, and movies… I never think about disentangling moments from my cumulative experience of culture that may have influenced me the most… it means more in its blended entirety than it does a series of key experiences or authors.” As the youngest artist to present at the Whitney Biennial in 2006 (he was 25 at the time), Trecartin’s first major work, A Family Finds Entertainment, has since become a seminal piece of video art; it's hyperactive pace and kitsch surrealism are now iconic (the word “Trecartin-esque” is a surprisingly common art-world adjective). The curator Jeffrey Deitch once described Trecartin as “one of the first artists whose work looks and feels like life today.” Casting friends and family members, Trecartin’s characters are like mutant humans of the very-near future who have been distorted and morphed into alien others by their television sets. His delirious narratives of banal, suburban dramas offer a kind of every-day dystopia that perfectly embodies our current state of media inundation and ubiquity. The result is an uncomfortable mixture of the comically absurd and the unsettlingly familiar.

RELATED ARTISTS: Lizzie Fitch, Cory Arcangel, Petra Cortright, Allan Kaprow, Bruce Nauman

RELATED ARTICLES: "We Had Our First Red Bulls Together": Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin on Their Dusk-Till-Dawn Collaborative Process

RELATED ARTICLES: "We Had Our First Red Bulls Together": Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin on Their Dusk-Till-Dawn Collaborative Process

...

Now that you have an understanding of how art can progress from one artistic innovation to the next, you can probably see why people get so excited about what living avant-garde artists are making now, anxiously anticipating what might be the next big thing in the ever-evolving history of art! For a look at the up-and-coming artists of today, check out Artspace's monthly Artists to Watch series.

No comments:

Post a Comment