COLLECTING 101

The Evolution of Art: Artworks That Advanced Our Understanding of the Medium, Part I

A couple million years ago, humans discovered fire, and in 1879 Thomas Edison manufactured a lightbulb. Today we take both fire and electricity for granted—but these discoveries were never obvious, and though they were made millions of years apart from one another, they aren't completely independent, either; to get from one to the next, humans made crucial innovations that not only advanced the linear progression of science and technology, but opened our imaginations to what could be possible in the future. Art is no different.

Today, art can be almost anything. But there was a time in the not-so-distant past when abstraction was inconceivable, and it was believed that art could only represent something that already existed in the real world. There was a time when an object couldn't be considered art unless it showed evidence of the artist's touch. And until relatively recently, processes like silkscreen printmaking or the use of industrial materials like steel were considered off-limits in the realm of fine art.

So, how did we get to where we are today? Who were the artists that changed the course of art history? And what were the artworks that broke the mold? Though you've probably heard of most of the artists in the list we present to you below, we're here to explain what discovery each artist made, and how they effectively changed the definition of art. In this two-part series, we'll first describe the advances in Modern art beginning with Duchamp's urinal and ending with Donald Judd and the Minimalists in 1969. In Part II, we'll introduce some of the more recent developments leading up to art today.

1. The Beginning of Abstraction

KAZIMIR MALEVICH

KAZIMIR MALEVICH

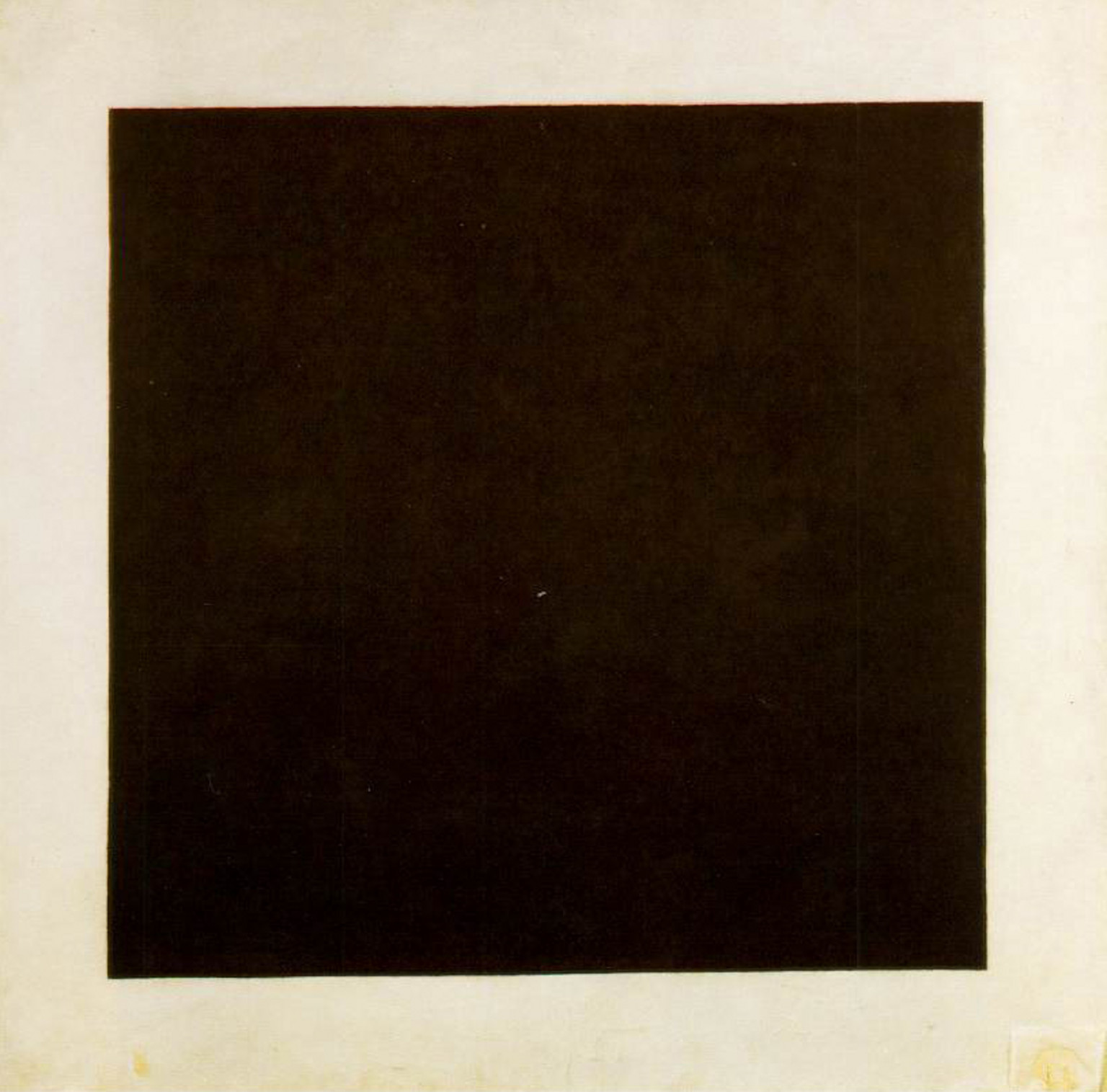

Black Square (c. 1915)

Now it’s hard to imagine that this simple black painting could land anyone in prison—but believe it or not, embedded in the thick layers of black paint (art critic Peter Schjeldal once described them as “juicy”) lies a profound philosophical subversion that made Russian artist Kazimir Malevich a cultural criminal in the eyes of Joseph Stalin at the time. Debuted by the artist in 1915 in Petrograd, this modestly sized painting (it measures only 31 inches on each side) radically demonstrated a shift in art, laying the foundation for abstract painting.

Art previously had been representational. In other words, painters painted subjects like people (think Van Gogh's portraits), places (like Monet's lily-pad-studded landscapes), and things (Cézanne's still lifes, for example). But Malevich sought to liberate art from what he saw as the shackles of pictorial representation, and instead argued for "the supremacy of pure artistic feeling." For him, this pure artistic feeling materialized as a black square, devoid of any reference to anything outside of the artwork itself. This was the beginning of abstraction, or more specifically, non-objective painting (also referred to as non-representational painting): painting that didn't replicate anything in the real world.

Malevich formed a new philosophy that he called "Suprematism," now often cited as the “zero point of painting." In Part II of his book The Non-Objective World (published in Munich in 1927), Malevich writes: “Under Suprematism I understand the primacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist, the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth.” A devout Christian mystic, Malevich’s work invokes spirituality without objectivity, appealing to pure and universal feeling. “Malevich is monumental not for what he put into pictorial space,” writes Schjeldal, “but for what he took out: bodily experience, the fundamental theme of Western art since the Renaissance.”

This was, unfortunately, viewed as entirely at odds with the state approved Social Realism of the time, and landed the pioneering artist in prison. He was officially accused of being a “formalist,” using complex techniques and forms seen as only accessible to the elite rather than being simple and “for the people.” For Malevich, this analysis couldn't be further from the truth; to him, art should be free of logic and reason, allowing us to perceive an absolute truth only realized through pure feeling. What could be more simple?

RELATED ARTISTS: Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin, El Lissitzky, Ljubov Popova, Naum Gabo

RELATED ARTICLE: Rise, Comrades! 6 Revolutionary Artworks of the Russian Avant-Garde You Should Know

RELATED ARTICLE: Rise, Comrades! 6 Revolutionary Artworks of the Russian Avant-Garde You Should Know

2. The Readymade

MARCEL DUCHAMP

The Fountain (1917)

If you’re looking at this piece, thinking, “You’ve got to be kidding me,” good for you! This notorious work of art was submitted to the 1917 Society of Independent Artists as one big joke. Designed by the French-American artist Marcel Duchamp as an elaborate prank poking fun at the American avant-garde, the work established a precedent that forever redefined what constitutes a work of art. The Fountain was the first example of what's now called "the readymade": an ordinary object that becomes art merely due to its context; otherwise it's just an ordinary object. This particular ordinary object, however—a urinal—was Duchamp's way of thumbing his nose at the institution. In the words of philosopher Stephen Hicks, “Duchamp did not select just any ready-made object to display. In selecting the urinal, his message was clear: Art is something you piss on.”

Rejected by the Society for being “immoral,” The Fountain was fiercely defended by critics who celebrated the work for revealing a revolutionary relationship between artist and artwork. According the those critics, The Fountain shows that an artist’s labor has nothing to do with their work’s merit—that an artwork is imbued with cultural significance automatically as soon as an artist calls it "art." As Duchamp puts it, “An ordinary object [could be] elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist.” It isn’t the aesthetic, technical, or material properties of a piece that give it value—it is the artist’s will.

For Duchamp, art should not soley be intended to please the eye (Duchamp called this kind of art "retinal art"). Instead, art should serve the mind. Duchamp's decision to show a urinal in a gallery would become known as one of the most important gestures in what's called "Conceptual Art," or art that asks us to question our most fundamental understandings of cultural value and artistic production.

RELATED ARTISTS: John Cage, Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth

RELATED ARTICLE: How to Think About Conceptual Art

RELATED ARTICLE: How to Think About Conceptual Art

3. Abstract Expressionism

JACKSON POLLOCK

Full Fathom Five (1947)

Often cited as the forefather of what American art critic Harold Rosenberg calls “action painting,” Jackson Pollockmade gestural paintings that he described as “motion made visible memories arrested in space.” Unlike Duchamp and conceptual artists who depended on theoretical concepts to define their artworks, Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists (often abbreviated as AbEx) considered painting an action, not an object. For Pollock, paintings are surfaces that document the interactions between painter and paint. He believed that, in rejecting pictorial traditions, he could access a more essential form of personal expression—one that was raw and unfiltered, and espoused a Jungian, primal way of being. Drips and splatters of paint became his visual vocabulary, freeing painting from object and subject in favor of pure gesture.

He even liberated painting from the canvas, removing the traditional up, down, left, and right orientations of the easel by laying his un-stretched canvases on the ground. This gave him the opportunity to work all around his painting instead of directly in front of it. Orientation becomes lost in his works and the viewer is allowed to, as Pollock suggests, “look passively and try to receive what the painting has to offer and not bring a subject matter or preconceived idea of what they are to be looking for.”

RELATED ARTISTS: Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell

RELATED ARTICLE: Dealer Betty Parsons Pioneered Male Abstract Expressionists—But Who Were the Unrecognized Women Artists She Exhibited?

RELATED ARTICLE: Dealer Betty Parsons Pioneered Male Abstract Expressionists—But Who Were the Unrecognized Women Artists She Exhibited?

4. Pop Art

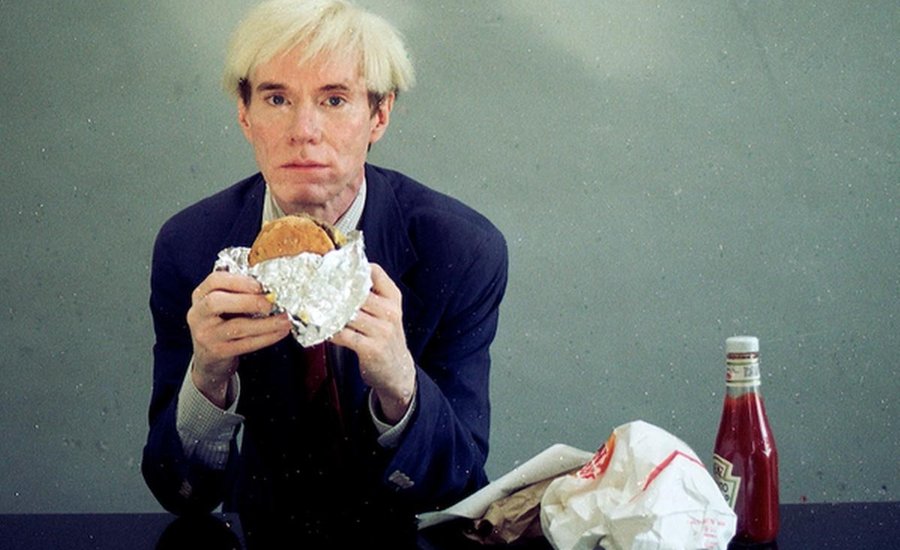

ANDY WARHOL

Campbell's Soup Cans (1962)

By the 1960s, Abstract Expressionism had become cliché, and Andy Warhol saw an opportunity to reintroduce images into the realm of fine art. Warhol broke the mold by completely renegotiating the relationship between the artist and the art object, and he did this in several ways. First of all, the enigmatic Warhol cast an aura around him that elevated him to a celebrity figure, unabashedly embracing the cult of the artist, and the use of social status to further his career. Secondly, he found inspiration and source material in the visual language of commercial culture, using not only imagery taken from advertising and product packaging (like the Campbell’s soup cans), but also by employing techniques and methods typically used by commercial industries—like silkscreen printmaking—to mass produce his work. Which brings us to the third historically significant element of Warhol’s work: The Factory. An army of hired assistants in Warhol's "factory" studio produced Warhol’s work for him, dissolving the idea that the artist's “hand” must be visible in a work of art, and instead, embraced transparency for the notion that art production is in fact a business.

As for Campbell’s Soup, “I used to drink it," Andy Warhol once said. "I used to have the same lunch every day, for 20 years, I guess, the same thing over and over again." In 1962 Warhol reproduced the can over and over again, mimicking the repetition and uniformity of advertising, changing only the label graphic on each one. By reproducing the image found in advertising, Warhol envisioned a new type of art that both criticized and celebrated mass consumer culture. Today, we call this type of art Pop Art.

RELATED ARTISTS: Richard Hamilton, James Rosenquist, Claes Oldenburg, Ed Ruscha, David Hockney, Roy Lichtenstein

RELATED ARTICLES: Warhol Had a Wife? 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Pop Master

RELATED ARTICLES: Warhol Had a Wife? 10 Things You Didn't Know About the Pop Master

C5. Minimalism

DONALD JUDD

Untitled (1969)

Highly critical of the Abstract Expressionists’ reliance on the mark of the artist, Donald Judd wanted to create art that was independent of his own subjectivity, art that had no evidence of the artist's hand. Adopting materials and techniques typically reserved for industrial applications—like steel, concrete, Plexiglass, and plywood—Judd and the Minimalists didn't want their artworks to reference or point to anything outside of the works themselves. This notion of "self-referentiality" is akin to Kazemir Malevich's ideas—both artists found a common enemy in the traditional illusionistic and representational ideologies of art.

Judd used the term “Specific Objects” to describe his own three-dimensional works—“specific” in that they were meticulously designed by the artist, “objects” in that they were fabricated as opposed to sculpted. His practice of using fabricators to realize his objects (like Warhol) revolutionized methods of art production, though not without eliciting severe criticism. In one particularly heated 1966 panel discussion at the Jewish Museum, AbEx artist Mark di Suveroderided Judd: “Real artists make their own art,” he said. Judd replied simply: "Methods should not matter as long as the results create art.” For Minimalists, it doesn't matter who physically makes the art—what's important is who conceived of the art. In Judd’s words, “A work can be as powerful as it can be thought to be.” Though the bright colors and graphic images of Andy Warhol and Pop Art may not seem to bare any relation to the stark sculptures of Minimalism, both movements shared the radical and revolutionary perspective that the value of an artwork didn't necessarily rely on the craftsmanship of the artist.

RELATED ARTISTS: Dan Flavin, Richard Serra, Robert Morris, Ellsworth Kelly, Carl AndreRELATED ARTICLE: The Intellectual Origins of Minimalism

RELATED ARTISTS: Dan Flavin, Richard Serra, Robert Morris, Ellsworth Kelly, Carl AndreRELATED ARTICLE: The Intellectual Origins of Minimalism

...

Now that you have an understanding of how art can progress from one artistic innovation to the next, you can probably see why people get so excited about what living avant-garde artists are making now, anxiously anticipating what might be the next big thing in the ever-evolving history of art. Next week we'll write about five more artists who have made important contributions since Donald Judd, and catch you all the way up to the present day.

No comments:

Post a Comment