Escape Artists: Why These 7 Creatives Disappeared from the Art World

In 1923, rumors circulated that renowned artist Marcel Duchamp was renouncing art to devote his life to chess. “I am still a victim of chess,” he explained at the time. “It has all the beauty of art—and much more. It cannot be commercialized. Chess is much purer than art in its social position.” Duchamp’s retreat from the art world wasn’t total, however. Instead, it gave him space, away from the distractions of the art scene and its attendant market pressures, to make his final work (in secret) for the last 20 years of his life.

Throughout history, many great artists have opted out, taken significant breaks, or withdrawn from the art world altogether—whether in search of a mind-clearing reprieve from commercial and social stresses, as with Agnes Martin, or as the final act of a practice animated by institutional critique, like Lee Lozano. Below, we take a look at seven such instances.

Marcel Duchamp

B. 1887, D. 1968

Arguably art history’s greatest disruptor, Duchamp came up with his most radical act when he abandoned artmaking in favor of chess. He had risen to fame for his iconoclastic artworks and antics in the years prior. Paintings like Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) (1912) scandalized the art world in 1913, and readymades like Fountain (1917), a urinal presented as a sculpture, would forever change the way we make and interpret art. But as early as 1918, Duchamp began a gradual retreat from the public art world, a shift evidenced by his decision to stop painting. He declared the medium bankrupt, saying “I never had the enthusiasm of a professional painter. With me it was the idea that counted more.”

Duchamp also expressed an increasing aversion to the avant-garde art scene in Paris, which he described derisively as “a basket of crabs.” While he did spend much of his time playing chess after 1923, even participating on the French national team for several years, Duchamp continued to make art in secret. (In a covert room in Greenwich Village, known only to he and his wife, he toiled on a single work, his masterpiece Étant donnés, 1946-1966, for 20 years.) The provocateur remains the father of anti-art, engaging in the act of retreat or refusal as a generative form of art-making.

Agnes Martin

B. 1912, D. 2004

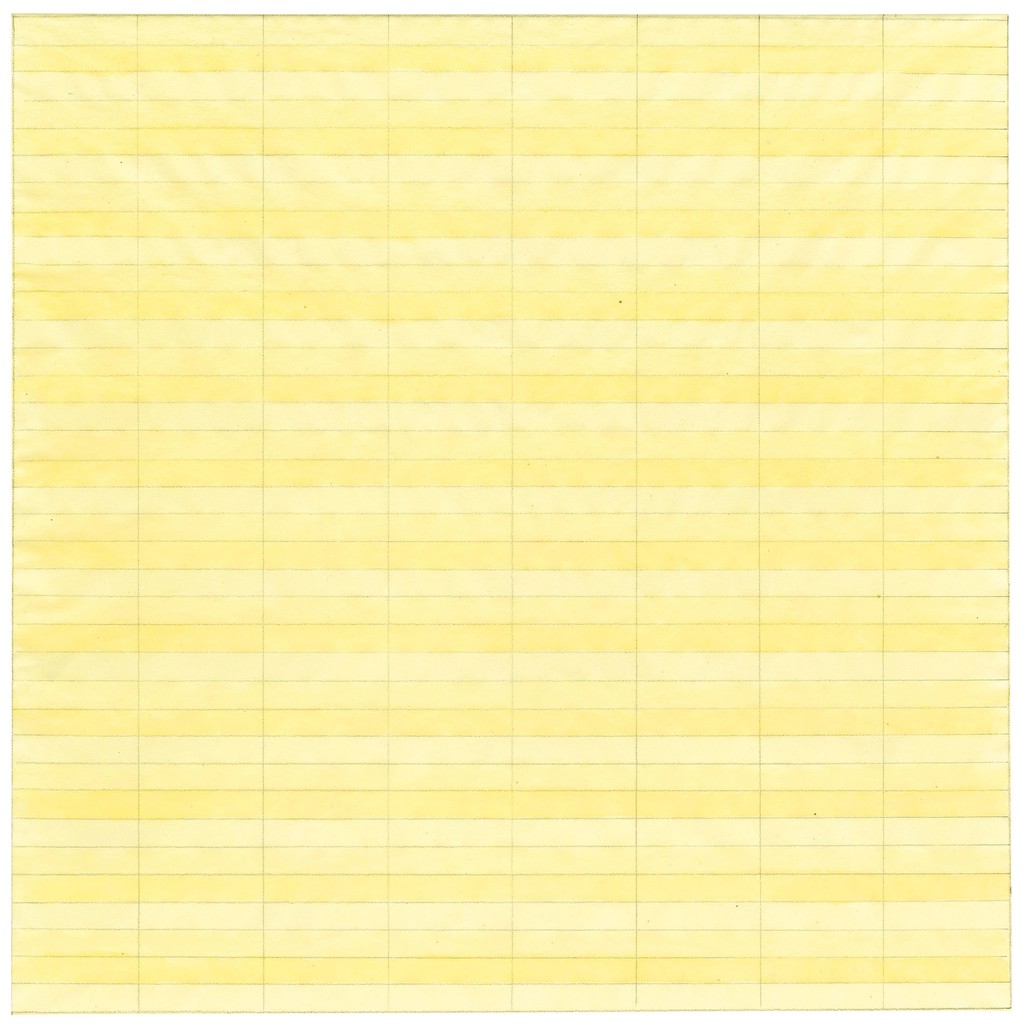

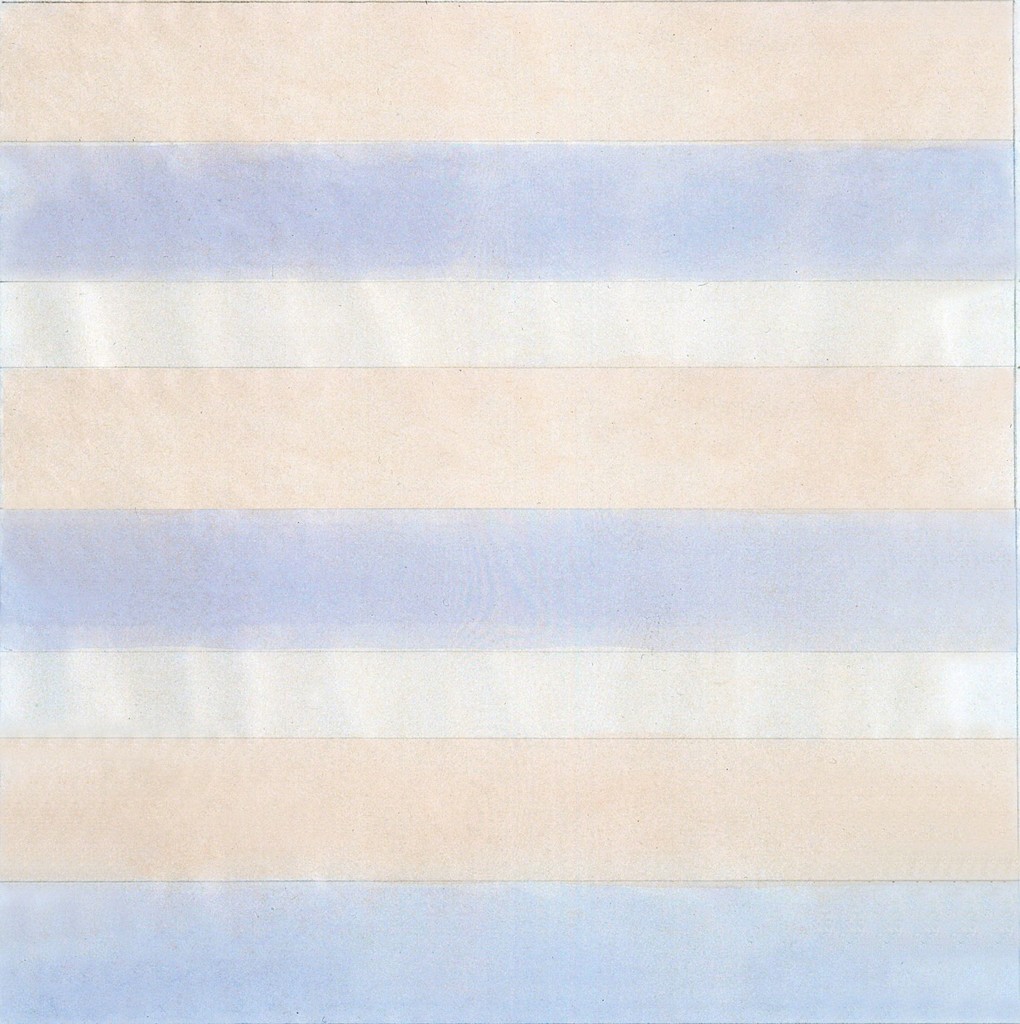

Martin abruptly disappeared from the New York art world in 1967, just after her starkly minimalist paintings had begun to receive acclaim from gallerists like Betty Parsons and artists such as Jasper Johns and Ellsworth Kelly, her neighbors in a ramshackle downtown New York studio building called Coenties Slip. Martin had always worked somewhat reclusively, shying away from the spotlight and the wider art scene. (The era’s rough-and-tumble Abstract Expressionist gatherings at Cedar Tavern took place just a few blocks north; Martin did not participate.) “At that time, I had quite a common complaint of artists—especially in America,” she later explained of her retreat. “It seemed to have been something that happens to all of us. From an overdeveloped sense of responsibility, we sort of cave in.”

After an 18-month hiatus, during which time she rambled through the more remote corners of the U.S. and her native Canada, Martin resurfaced in New Mexico and returned to painting in 1971. “It was only solitude that got her painting again,” explained dealer Arne Glimcher, a close friend of Martin’s until her death in 2004. Indeed, away from the avant-garde art world’s mercurial and critical center, she evolved her grid-based body of work, producing some of her most transcendent, colorful paintings. One such work, titled “With My Back to the World” (1997), references both her desire to embody internal forces in her work (as opposed to the external world) and the act of withdrawal that allowed her to continue making art.

Sturtevant

B. 1924, D. 2014

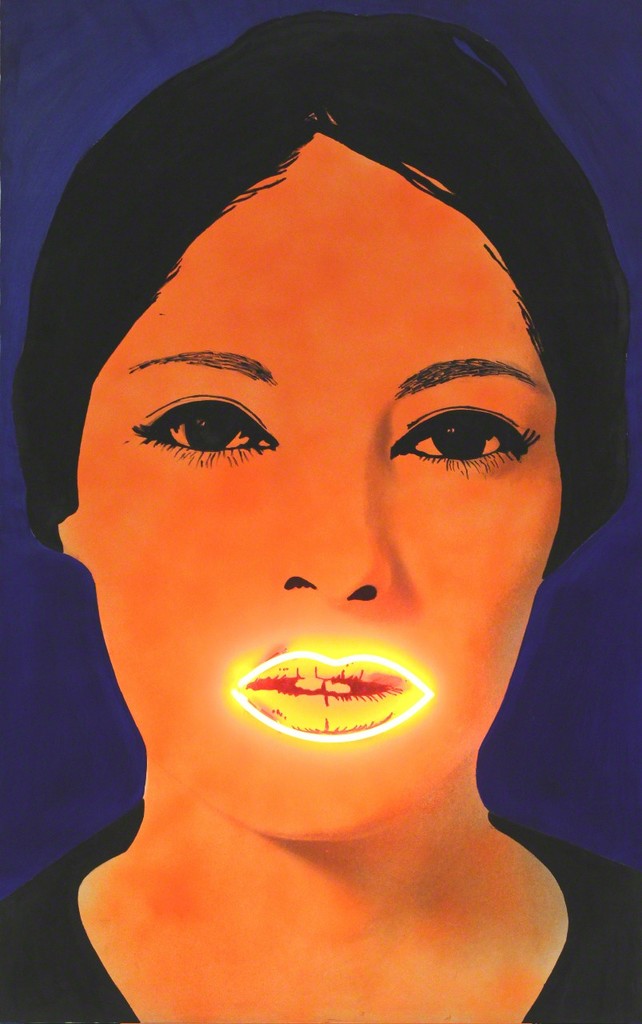

Sturtevant is now remembered as the bold progenitor of appropriation art, or as she preferred to describe it: “repetition.” In the mid-1960s, however, when she was vilified by artists like Claes Oldenburg, Sturtevant left New York and stopped making art for over a decade. “Oldenburg is ready to kill me. It all makes him dive up a wall,” she explained to Time magazine in 1969, two years after she recreated the pop artist’s seminal installation-cum-shop The Store several blocks from its Lower East Side home. For Sturtevant, however, her hiatus wasn’t so much an act of defeat as a proactive response to the hostility she encountered, which she felt undermined the power of her practice. “I don’t think I thrive on hostility, but I think I fight it with courage,” she explained in 1989.

Her retreat also solidified the conceptual framework of her practice—the investigation of artistic originality, authenticity, and legacy—and likewise enhanced the mystery that shrouded her life, which she took pains to keep under wraps. (She dropped her first name and rebuffed questions about her biography with a terse: “Dumb question.”) Sturtevant eventually resurfaced with new work in a 1986 exhibition at New York’s White Columns, and continued to make art through the end of her life. Later pieces, like the 1998 video Copy without Origins, Self as Disappearance, hint at connections between her period of withdrawal and her unremitting interest in identity and originality.

Lee Lozano

B. 1930, D. 1999

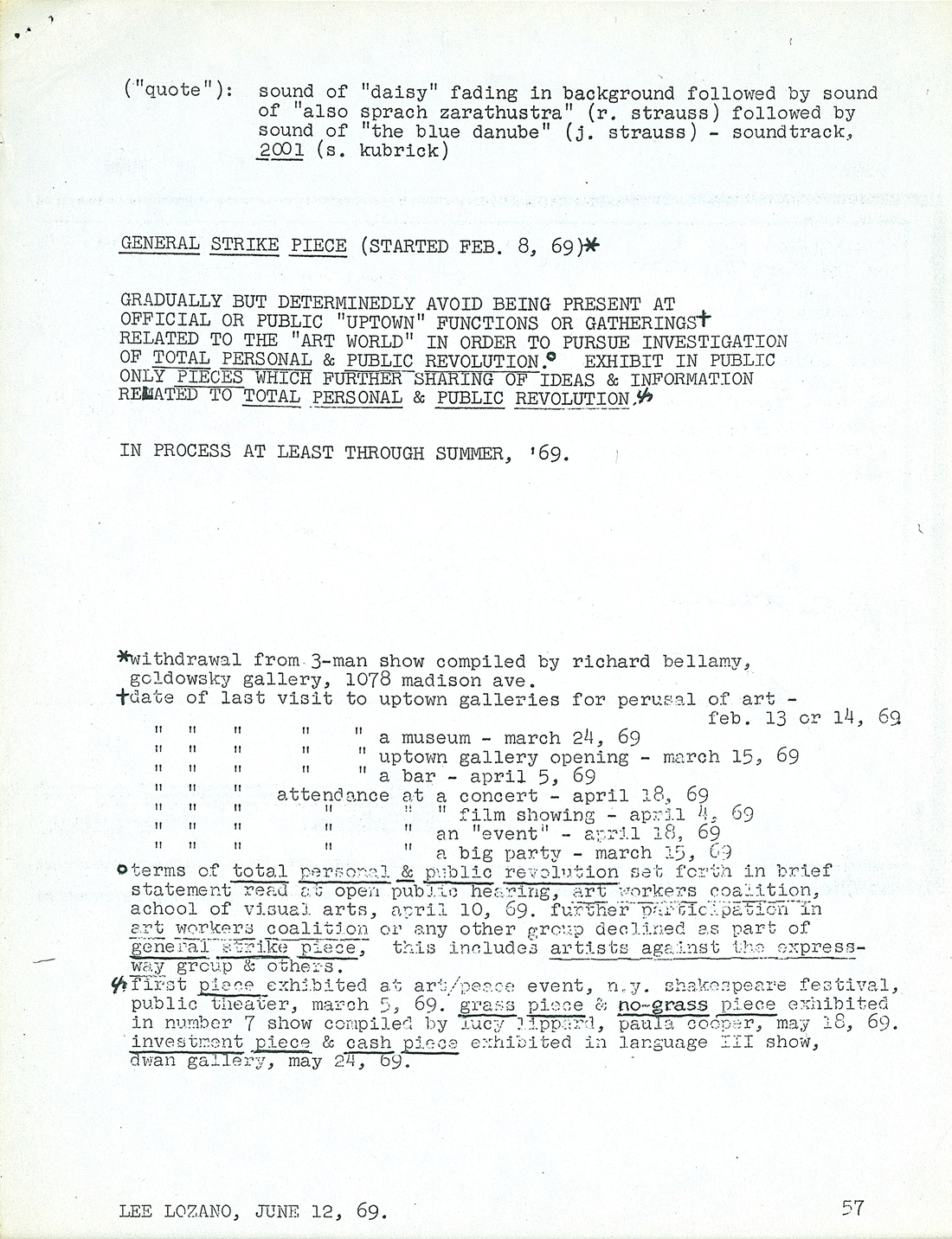

Lee Lozano, General Strike Piece, 1969; offset print; 28 cm x 21.5 cm; location in the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Jaap van Liere in 2001. Image courtesy of the Blanton.

Lee Lozano, General Strike Piece, 1969; offset print; 28 cm x 21.5 cm; location in the Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Jaap van Liere in 2001. Image courtesy of the Blanton.

Lozano brazenly broke into the male-dominated 1960s art world with subversive paintings of gyrating machines that resembled sexual organs. By the end of the decade, however, she had begun a work—Dropout Piece (1970)—that would culminate in her complete, self-induced removal from the New York art community, where she had become a fixture. Despite her successes in the city, she soon became disenchanted by what she saw as the art world’s vanity and embarked on her “Language Pieces” (1967-1971), a series of conceptual works that doubled as a systematic, ferocious takedown of the commercial art system’s failings. “Artist, critic, dealer and museum friends, in fact, almost everybody: I still smell on your bad breath the other people’s rules you swallowed whole so long ago,” she wrote in her journal in 1968.

This sentiment gained momentum with General Strike (1969), in which she documented her retreat from the art world as a timeline of final appearances: “Last time at an opening: March 15. Last big party: March 15. Last museum visit: March 24.” Then, in 1971, a year after mounting her solo show at the Whitney Museum (a rare feat for a living woman during the era), she launched Decide to Boycott Women, an expression of her frustration with the feminist movement, and began her Dropout Piece (1972), which climaxed in her complete withdrawal from the art world and the end of her practice. (The piece has been described by curator Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer as her “greatest act of art and endurance.”) Lozano’s work was then largely forgotten. Her influence as a minimalist and conceptual art pioneer has only recently been resuscitated, placed in the context of other important artists—such as Vito Acconci and Adrian Piper—whose work fuses institutional critique with raw personal experience.

Charlotte Posenenske

B. 1930, D. 1985

In 1968, after a nearly 10-year-long stint exhibiting her radical minimalist sculptures alongside the likes of Donald Judd, Carl Andre, and Dan Flavin, Posenenske renounced artmaking, which she saw as politically and socially impotent. “Though art’s formal development has progressed at an increasing tempo, its social function has regressed,” she wrote in her 1968 manifesto just before exiting the art world. “It is difficult for me to come to terms with the fact that art can contribute nothing to solving urgent social problems.”

While Posenenske devoted the remainder of her life to sociology, she left behind a body of work—and powerful writings—that would go on to influence the direction of minimalist and conceptual art, steering them towards social commentary and institutional critique. Her towering, hard-edged sculptures made from industrial, workaday materials like galvanized steel and corrugated cardboard, could be assembled by anyone—an essential, democratic property of her late work, and an attempt at soldering art and social engagement.

Cady Noland

B. 1956

After Noland’s breakout show at New York’s White Columns in 1988, she mounted no less than six solo presentations in the following two years—a supersonic ascent. But by 1999, at the age of 43, she unveiled what has become known as her last exhibition. From the beginning, Noland’s sculptures and large-scale installations were driven by her distaste for the commoditized, media- and fame-obsessed tendencies of American culture. In one series, she printed found images of murdered or spurned celebrities onto metal, perforating them through erasure or adorning them sardonically with American flags.

“From the point at which I was making work out of objects, I became interested in how...people treat other people like objects,” she explained in a 1990 interview. This sentiment became increasingly intertwined with an aversion toward the commercial art world and her own position as a famous person within it (or perhaps tethered to it), crescendoing with her retreat in 1999. While institutions and galleries have exhibited her work since, they have done so without her involvement. And on the rare occasion that a piece does crop up, it usually comes with a caustic disclaimer from Noland herself; in 2014, a placard next to her installation at the Brant Foundation read: “The artist, or C.N., hasn’t given her approval or blessing to this show.”

Maurizio Cattelan

B. 1960

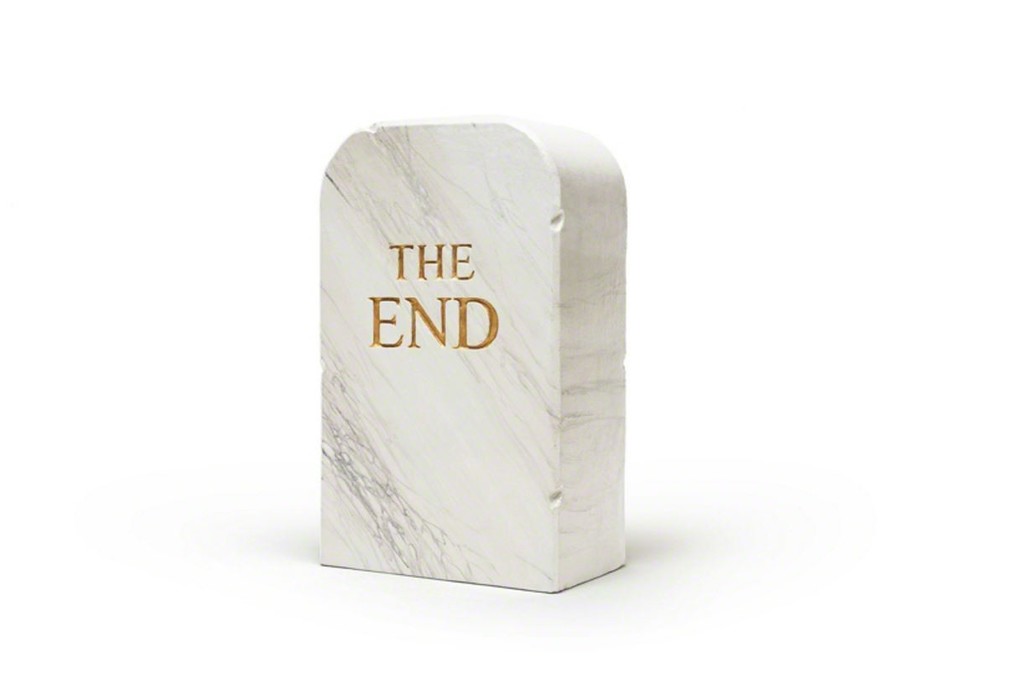

Cattelan’s last act as an artist came, at least in theory, when he dangled the bulk of his wry, disquieting body of work from the Guggenheim’s ceiling for his 2011 retrospective. “You ever feel tired and want to change occupations?” he asked in a statement announcing his retirement. “If you were in a band, you might feel you start to repeat yourself.” The rabble-rousing artist’s career—which helped to shape relational aesthetics and a new wave of conceptual art that fused sculpture and social commentary—has been marked by such surprises and spectacles.

“I pretended to be dead, but I could still see and hear what was happening around me,” he said of his retirement in 2015. “My works were there, available for curators to build their exhibitions, to test the works’ strength, to exploit their potential, and until now I didn’t want to interfere with these experiments.” Though after the appearance of a new Cattelan work at Manifesta 11 in June (a wheelchair that traveled biblically across Lake Zurich), it seems that the artist’s short-lived hiatus was an artwork in itself—and perhaps fodder for more ambitious pieces to come.

—Alexxa Gotthardt

No comments:

Post a Comment