Analysis

Artiquette: 10 Tips for Pricing an Artwork

What is the single-most important thing to remember?

Artiquette is a series that explores etiquette in the art world.

The sands of the art market are always shifting. An artist’s work could be selling for record highs at auction one year and below estimates the next. For a dealer, figuring out where the value of your artists’s work falls on the spectrum—whether it’s a massive installation by a blue-chip artist, a painting by an emerging talent, or editioned prints—can be a daunting proposition.

To help us break it all down, artnet News spoke to Cristin Tierney of Cristin Tierney Gallery about the major considerations she takes into account when determining the price of each and every work that passes through her establishment.

Related: Artiquette: 7 Things Not to Do on a Studio Visit

“From the outside looking in, it’s kind of byzantine,” she told artnet News. “We all do this all the time and we think about it all the time, but articulating it is tricky.”

Even though it’s not an exact science, figuring out how to appropriately price a work of art is actually fairly straightforward process.

1. When in doubt, look to past results.

1. When in doubt, look to past results.

“One of the first things we think about is price history,” said Cristin Tierney. How an artist has sold in the past is an excellent yardstick by which to predict future performance.

2. Compare, compare, compare.

When you’re working with a younger artist who might not have much of an existing track record, look to sales of comparable work by artists at a similar point in their career. “The single-most important thing to remember is that it’s very much about comparison,” Tierney explained. “You’re always thinking in terms of comparison. You do that because your clients will do that too.”

Related: Artiquette: How to Take a Winning Selfie With an Art Star

3. Consider both the primary and secondary market for an artist.

The longer an artist has been around, the more likely it is that their work will turn up at auction. “Often the primary market and even the private secondary market is very different than auction pricing,” said Tierney. Sometimes, there’s a big difference in what a work sells for in the various realms.

But that doesn’t just mean that an artist who has grown in renown will suddenly start hammering down at high price points: “It can go both ways,” Tierney explained, noting that for some artists, their best work often winds up in the hands of friends, dedicated collectors, or museums who rarely part with it, leaving lesser works to make up the bulk of their auction history. “There are some artists that can really pop at auction and then other artists that do better selling privately,” she added. “There’s all kind of reasons on the secondary market why things don’t add up.”

4. You don’t want to be an outlier.

4. You don’t want to be an outlier.

“There’s nothing worse than everyone having a slightly different price,” noted Tierney. “Not only is it not cool if you’re the person looking to buy the work, but you pretty much look like an idiot if you do that.” For the art market to function, “everybody has to be on the same page.”

“You know that if you price something ridiculously high, it’s just not going to sell,” Tierney added. “There’s a threshold for clients.” (Over-priced artwork also angers collectors.)

Related: Artiquette: 7 Tips for Surviving a Gallery Dinner

5. Proof of authenticity is a big factor.

Sadly, we’re all familiar with the tale of the unlucky collector who almost certainly owns a masterpiece, but can’t sell it because no one in a position of authority will vouch for its authenticity. (See Richard Avedon’s master printer’s set of prints, the unconfirmed Mark Rothko from the California School of Fine Arts, and Greece’s cursed van Gogh.)

One of Tierney’s own artists, Peter Campus, had a video piece that sold at auction a few years ago for less than $1,000, even though the gallery prices similar works at around $18,000. “It had no certificate—[the seller] never contacted us about it to get any of the proper paperwork and authentication,” Tierney recalled. “We didn’t protest it or anything, but it sold for pretty much nothing.”

6. Take condition into consideration.

6. Take condition into consideration.

A pristine, mint-condition print is a totally different animal from one faded by years of exposure to the sun, and the price will absolutely reflect that. “Condition is incredibly important—the same image can sell for half as much,” said Tierney.

7. Don’t be afraid to have a conversation.

A second opinion is always a good idea. “We definitely talk to our colleagues and other people who represent an artist or an estate,” Tierney said. “People don’t realize how collegial the art market can be.”

Related: Artiquette: 11 Things Not To Do at an Art Auction

“If I’m having trouble finding the right kind of price I don’t hesitate to call one of my colleagues and talk some things through,” she added. “People are honest about whether things are actually selling.”

8. Think about who the audience is.

8. Think about who the audience is.

For a conceptual artist that might have less commercial appeal, sellers won’t price it as aggressively, Tierney said, because “the heart of that market is institutional,” and museums don’t have the deep pockets of wealthy collectors.

9. Scope out the art fairs.

Outside of your immediate circle of friends and colleagues, the art fairs, which unite gallerists from around the world in a single room, are another important resource to find out what prices make sense for your artwork. “Art fairs are hugely helpful—just like everybody else,” said Tierney, “we’re all running around and asking for prices.”

10. You can only go so low.

Especially large-scale pieces sometimes seem made for museums, as only the wealthiest collectors really have the space to store and display them. “You want to be flexible with how you price it,” said Tierney, but big work often comes with a big price tag. “A 32-foot installation can’t be priced at $20,000, obviously,” Tierney said. “There are production costs and things like that have to be factored in as well. It really can vary based on the installation.”

Follow artnet News on Facebook.

The sands of the art market are always shifting. An artist’s work could be selling for record highs at auction one year and below estimates the next. For a dealer, figuring out where the value of your artists’s work falls on the spectrum—whether it’s a massive installation by a blue-chip artist, a painting by an emerging talent, or editioned prints—can be a daunting proposition.

To help us break it all down, artnet News spoke to Cristin Tierney of Cristin Tierney Gallery about the major considerations she takes into account when determining the price of each and every work that passes through her establishment.

Related: Artiquette: 7 Things Not to Do on a Studio Visit

“From the outside looking in, it’s kind of byzantine,” she told artnet News. “We all do this all the time and we think about it all the time, but articulating it is tricky.”

Even though it’s not an exact science, figuring out how to appropriately price a work of art is actually fairly straightforward process.

The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF), Maastricht, 2013. Courtesy photographer Harry Heuts/TEFAF.

“One of the first things we think about is price history,” said Cristin Tierney. How an artist has sold in the past is an excellent yardstick by which to predict future performance.

2. Compare, compare, compare.

When you’re working with a younger artist who might not have much of an existing track record, look to sales of comparable work by artists at a similar point in their career. “The single-most important thing to remember is that it’s very much about comparison,” Tierney explained. “You’re always thinking in terms of comparison. You do that because your clients will do that too.”

Related: Artiquette: How to Take a Winning Selfie With an Art Star

3. Consider both the primary and secondary market for an artist.

The longer an artist has been around, the more likely it is that their work will turn up at auction. “Often the primary market and even the private secondary market is very different than auction pricing,” said Tierney. Sometimes, there’s a big difference in what a work sells for in the various realms.

But that doesn’t just mean that an artist who has grown in renown will suddenly start hammering down at high price points: “It can go both ways,” Tierney explained, noting that for some artists, their best work often winds up in the hands of friends, dedicated collectors, or museums who rarely part with it, leaving lesser works to make up the bulk of their auction history. “There are some artists that can really pop at auction and then other artists that do better selling privately,” she added. “There’s all kind of reasons on the secondary market why things don’t add up.”

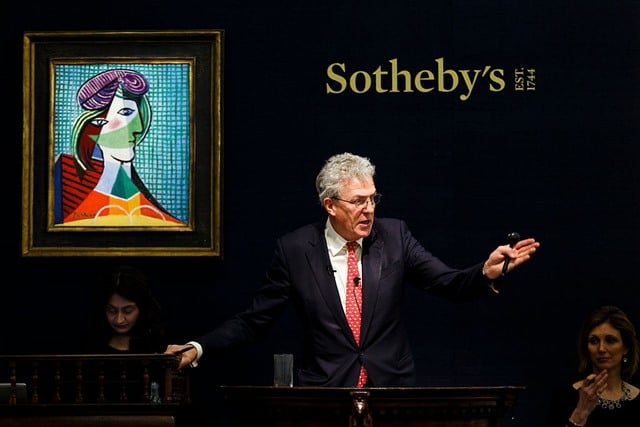

Sotheby’s auctioneer Henry Wyndham at the auctioneer’s London salesroom in February 2016. Courtesy Tristan Fewings/Getty Images.

“There’s nothing worse than everyone having a slightly different price,” noted Tierney. “Not only is it not cool if you’re the person looking to buy the work, but you pretty much look like an idiot if you do that.” For the art market to function, “everybody has to be on the same page.”

“You know that if you price something ridiculously high, it’s just not going to sell,” Tierney added. “There’s a threshold for clients.” (Over-priced artwork also angers collectors.)

Related: Artiquette: 7 Tips for Surviving a Gallery Dinner

5. Proof of authenticity is a big factor.

Sadly, we’re all familiar with the tale of the unlucky collector who almost certainly owns a masterpiece, but can’t sell it because no one in a position of authority will vouch for its authenticity. (See Richard Avedon’s master printer’s set of prints, the unconfirmed Mark Rothko from the California School of Fine Arts, and Greece’s cursed van Gogh.)

One of Tierney’s own artists, Peter Campus, had a video piece that sold at auction a few years ago for less than $1,000, even though the gallery prices similar works at around $18,000. “It had no certificate—[the seller] never contacted us about it to get any of the proper paperwork and authentication,” Tierney recalled. “We didn’t protest it or anything, but it sold for pretty much nothing.”

A painting sold by Knoedler as a Mark Rothko that turned out to be fake.

A pristine, mint-condition print is a totally different animal from one faded by years of exposure to the sun, and the price will absolutely reflect that. “Condition is incredibly important—the same image can sell for half as much,” said Tierney.

7. Don’t be afraid to have a conversation.

A second opinion is always a good idea. “We definitely talk to our colleagues and other people who represent an artist or an estate,” Tierney said. “People don’t realize how collegial the art market can be.”

Related: Artiquette: 11 Things Not To Do at an Art Auction

“If I’m having trouble finding the right kind of price I don’t hesitate to call one of my colleagues and talk some things through,” she added. “People are honest about whether things are actually selling.”

Jill Magid, Trust,

from “Evidence Locker” (2004), video still, in the new International

Center of Photography’s inaugural exhibition “Public, Private, Secret.”

Courtesy the International Center of Photography, © Jill Magid.

For a conceptual artist that might have less commercial appeal, sellers won’t price it as aggressively, Tierney said, because “the heart of that market is institutional,” and museums don’t have the deep pockets of wealthy collectors.

9. Scope out the art fairs.

Outside of your immediate circle of friends and colleagues, the art fairs, which unite gallerists from around the world in a single room, are another important resource to find out what prices make sense for your artwork. “Art fairs are hugely helpful—just like everybody else,” said Tierney, “we’re all running around and asking for prices.”

10. You can only go so low.

Especially large-scale pieces sometimes seem made for museums, as only the wealthiest collectors really have the space to store and display them. “You want to be flexible with how you price it,” said Tierney, but big work often comes with a big price tag. “A 32-foot installation can’t be priced at $20,000, obviously,” Tierney said. “There are production costs and things like that have to be factored in as well. It really can vary based on the installation.”

Follow artnet News on Facebook.

Share

Article topics

No comments:

Post a Comment