Reviews

The Ego-Centric Art World is Killing Art

JJ Charlesworth on what 2014 revealed about the future of art. It's not pretty.

Miley Cyrus at the opening of her exhibition “Dirty Hippie.”

Photo via: Miley Cyrus/Instagram.

Photo via: Miley Cyrus/Instagram.

But sometimes, it’s the more marginal developments that start to bug you. And one of the least appealing, and, yet, for me, most significant trends of 2014 was the rise of the noisy, empty celebration of the artist-as-ego. Or maybe that should be ego-as-artist. I’m not sure. Of course, the art world has always been full of pretty massive egos, so what’s new, right? Yet 2014 seemed to be the year in which the obsession with the most narcissistic expression of the individual started to take center stage. It points to the apparently unstoppable merging of art with a new form of celebrity culture, one in which individual self-expression has become an obsession above all other considerations.

I’m not talking here about the slew of big swinging, er, ego shows of mostly late-career male artists that peppered the year. Though, those kept coming on strong: the Whitney’s enthronement of Jeff Koons as “the most important, influential, popular, and controversial artist of the postwar era” (according to the Whitney’s crazed, hyperventilating publicity), the interminably pompous gravitas-lite of Anselm Kiefer’s retrospective at London’s RA, and minimalist god Richard Serra’s massive steel erections in the desert of Qatar, among them. When it came to career anointment, the big museums were happy to oblige, desperate as they are these days to pull a big crowd.

Marina Abramović.

Photo: Marco Anelli (2014), Courtesy of Serpentine Gallery.

Photo: Marco Anelli (2014), Courtesy of Serpentine Gallery.

Maybe I’m offending those for whom meditation, mindfulness, and finding one’s inner stillness is a big deal. Oh well, too bad. I never invite you to my parties anyway. The point is that, couched in the language of meditational self-realization, of “forgetting the past” and “living in the now,” Abramović’s recent work really only crystallizes and reflects the wider trend of contemporary culture: its narcissistic ideal of personal self-realization, of experiencing the now, of finding oneself, and (once you’ve found yourself) of being yourself. In short, it’s the cultural expression of Generation Y, or Generation Me, as US academic Jean Twenge styled it in her eponymous book of 2006.

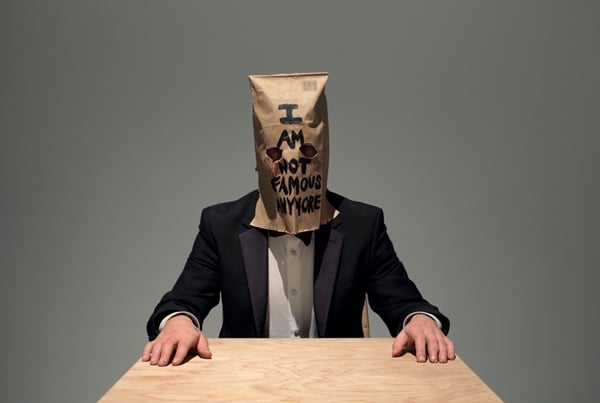

Generation Y’s culture is one that privileges self-expression over anything else. In 2014, that seems to have led to a lot of celebrities (admittedly mostly American celebrities) expressing themselves through the medium of art—or at least the medium of the art world. James Franco “reworked” the early works of Cindy Sherman with himself in the starring role. Shia LaBoeuf went on with his performance-art-styled antics in his gallery show “#IAMSORRY” (complete with his bizarre claim that he was raped by a female visitor).

Luke Turner, Shia LaBeouf, and Nastja Säde Rönkkö, #IAMSORRY (2014).

Photo: Courtesy the artists.

Photo: Courtesy the artists.

Too much of a stretch to tie the austere pseudo-spiritualist transcendentalism of Abramović to the moronic carnival of celebrity art? Not really. They may look poles apart, but they’re based on the same veneration of individual self-realization through self-expression in which it’s the process, not the product, that matters. Everyone, just “being themselves” and claiming to be art. It’s also why art shows are becoming experiences. The only show anyone really wanted to see, as I did my annual stop in Art Basel this summer, was Klaus Biesenbach’s and Hans Ulrich Obrist’s performance art museum-cum-fun-palace-cum-freaky-corridor-of-nightmares, “14 Rooms.” (It includes, of course, one piece by Marina Abramović.) Feeling an experience, being in the now, is the new aesthetic of Gen Y.

That’s why, even though those Alpha male artists might make a big show of themselves (Jeff Koons naked with just the leather gloves on in the gym! Help!), they’re way behind, stuck in the past. That’s because they’re from a generation that still thinks art should be about something other than me, here, right now. That art should be, say, about consumerism, or about the history of Germany, or even just about how massive huge chunks of Cor-Ten steel look when you stick them in a desert. In other words, about stuff you have to think about, maybe discuss, argue over with others, disagree about—something, which isn’t entirely about yourself. But, for now, between Miley and Marina, 2014 began to reveal the future of art: the artist and the audience, holding hands between infinity mirrors, one hand free to squeeze off a selfie.

JJ Charlesworth is a freelance critic and associate editor at ArtReviewmagazine. Follow @jjcharlesworth on Twitter.

Follow artnet News on Facebook.

Share

Article topics

No comments:

Post a Comment