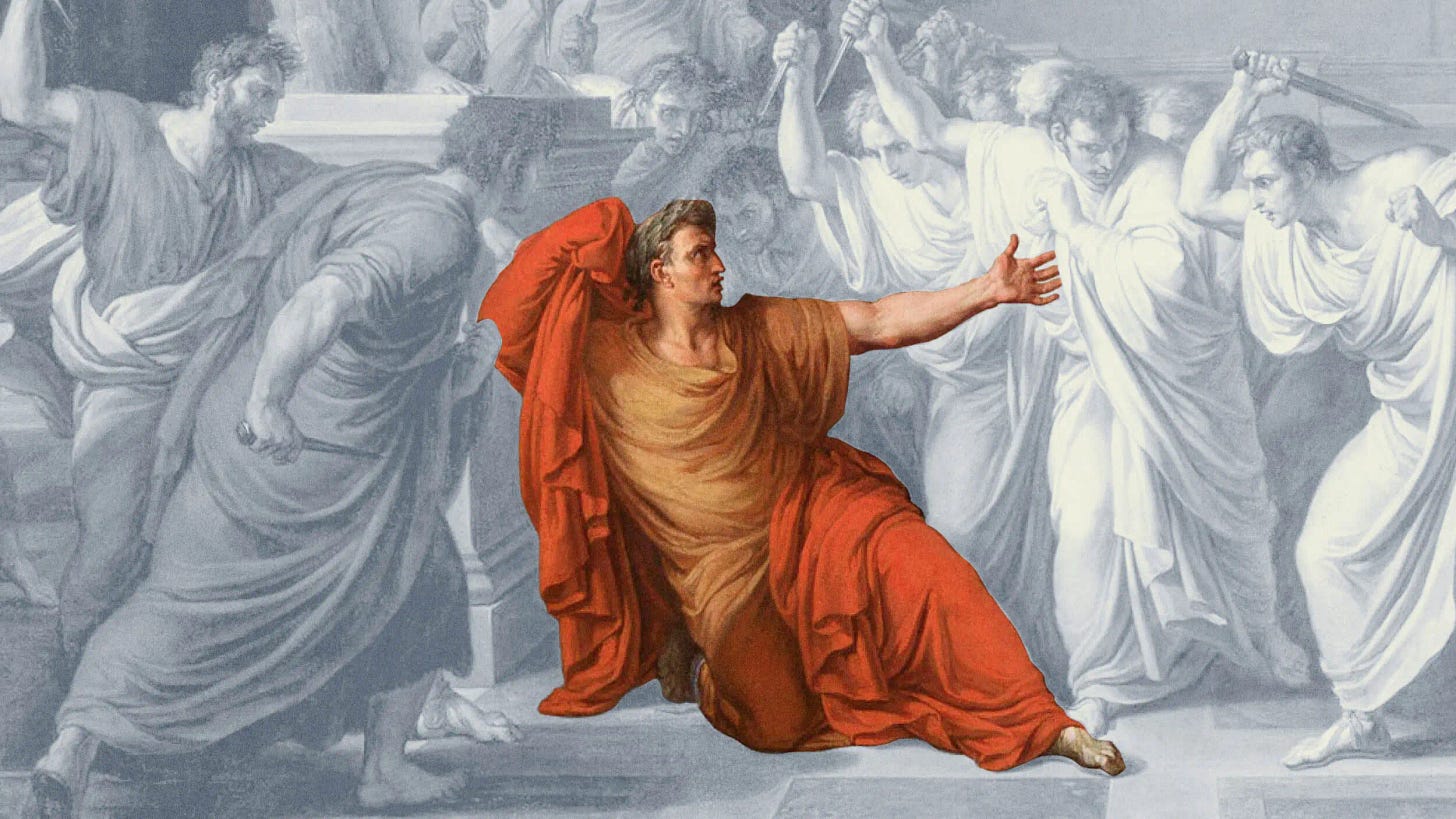

What the rise and fall of Julius Caesar can teach us about EQ

Julius Caesar conquered Gaul but his emotional intelligence was pitiful — and there’s plenty we can learn from his leadership deficiencies.

by Paul Vanderbroeck

In leadership discourse, the spotlight often falls on strategy, execution, vision, and charismatic influence. Yet one of the most persistent failure modes for even the most outstanding leaders lies not in what they do, but in what they fail to sense: the emotional currents around them, the whispers hidden behind applause. It turned out to be Julius Caesar’s fatal trap, a figure who conquered nations, reshaped Rome, and rewrote what leadership looked like. Caesar’s sudden and tragic end to his career at the hands of his followers was not due to arrogance or a power grab. It resulted from a deficit in emotional intelligence (EI or EQ), the quiet skill that sustains trust once one attains a leadership position. Something that Caesar could well have prevented.

A legendary rise — and an under-appreciated blind spot

Julius Caesar’s rise more than two millennia ago was stellar: both in Roman government and as a general. Ever since, Caesar remains one of history’s most compelling case studies in leadership. His career offers timeless lessons about influence, reputation, and human behavior inside large, competitive systems. His name lives on in the titles of Kaiser in German and Czar in Russian. Every reason therefore to study Caesar closely for valuable insights for today’s leaders.

When we examine how his career developed, a pattern emerges. It began early in his career, when he tried his hand as a lawyer. Although a brilliant speaker in court, he failed to influence the stakeholders who ultimately determined the trial’s outcome. After these mixed results, he switched to a political career, winning elections to various offices due to his strong performance and visibility. Yet, as a politician, he repeatedly failed to sway the Senate to his side when arguing proposals. In trying to persuade this powerful institution, Caesar’s rational arguments, although again always eloquently presented, lost against those of his opponents who managed to touch the irrational and soften self-interested drivers of the senators. Later, as a general, he thought he had conquered Gaul, only to be taken by surprise by the most significant uprising ever. A similar thing happened when he believed he had finally won the civil war, and, all of a sudden, a massive revolt broke out in Spain.

Caesar, brilliant as he was, was able to overcome these setbacks, but only with incredible difficulty. In Rome, he compensated by building a political organization that allowed him to circumvent the Senate by getting the people to vote on his proposals. At war, his brilliant generalship and loyal army enabled him to overcome the odds that threatened his victories. The conquest of Gaul is hailed as a great military feat. Yet few know that it not only almost slipped out of Caesar’s hand, but that he could have prevented this from happening. Similarly, the uprising in Spain almost cost him the victory in the civil war that he had just obtained after so much effort.

In all cases, his strengths of speed, innovation, organization, and execution — earmarks of his success — also saved him from disaster. What he did not do was pause and reflect on what had gone wrong in order to learn from it.

Caesar was unaware that discontent was brewing, and it all ended in the Shakespearean tragedy on the Ides of March 44 BC, when he was stabbed in the back.

When he had finally quelled all resistance and had become the sole ruler of Rome, he steamrolled on. His plans to reform Rome and its empire were sound, yet he implemented them with great speed and little consideration for buy-in. Since no one spoke up, he assumed everyone agreed. It brought about a coalition of important stakeholders. Some felt sidelined, aggrieved or became concerned about their own career prospects. Others mistook Caesar’s top-down approach for a desire to replace the Republic with a monarchy.

In any case, Caesar was unaware that discontent was brewing, and it all ended in the Shakespearean tragedy on the Ides of March 44 BC, when he was stabbed in the back.

What exactly went wrong?

Emotional intelligence is the key, as highlighted by KDVI (a leadership development firm). It’s defined as the ability to identify, control and recognize emotions, both in oneself and, to an extent, in others. Leaders with high emotional intelligence possess strong levels of self-awareness and can recognize, understand and regulate their own emotions. Moreover, they are adept at interpreting others’ emotional responses. This understanding empowers leaders to navigate complex situations with finesse and insight.

In Caesar’s case, it meant:

Missing emotional undercurrents among key stakeholders. Caesar failed to anticipate that stakeholders make decisions based on more than rational arguments only and that establishing peace meant winning hearts as well as minds.

Not realizing that a change of role results in a shift in expectations towards the leader. Having become the sole ruler of Rome, Caesar continued to use the same strengths that had brought him success before. Rather than staying in action mode, he should have switched to getting buy-in for his change program. A classic example of Marshall Goldsmith’s mantra “What got you here won’t get you there.”

Contemporary leadership lessons

What does the story of Caesar mean for the leader of today?

Emotional intelligence is not optional. Reading the room, sensing discontent, having an antenna for misunderstandings among followers is not only key to garnering support but also to preventing resistance that can endanger your success.

Don’t just measure what you do, but also how people feel about it. Make sure that you have your intelligence in order, so that you know what’s going on also further down in your organization: e.g. through surveys, town halls and surprise visits.

Adapt your style as your role changes. When taking on a new role, particularly after a promotion, it’s crucial to be aware not only of how your objectives have changed, but also of the expectations of your stakeholders. This awareness allows you to adapt your leadership style accordingly, ensuring you remain effective and influential.

Modern leaders must be vigilant and attentive to emotional undercurrents. Influence without trust can lead to isolation, and power without empathy can invite rebellion. The question we must ask constantly is not just ‘Are they listening to me?’ but ‘Do I hear what they are saying, particularly when they are not saying something?’. Julius Caesar didn’t, and the rest is history.

Check out more of Big Think’s content:

Big Think | Mini Philosophy | Starts With A Bang | Big Think Books

No comments:

Post a Comment