Never have we produced more images than at the time of their death. A million sharp knives carefully planted into the beating heart of the image. It looks around. Et tu? Yes, you. Yes, I. Yes, we. We have killed the image. 2025 will go down as the year the image died.

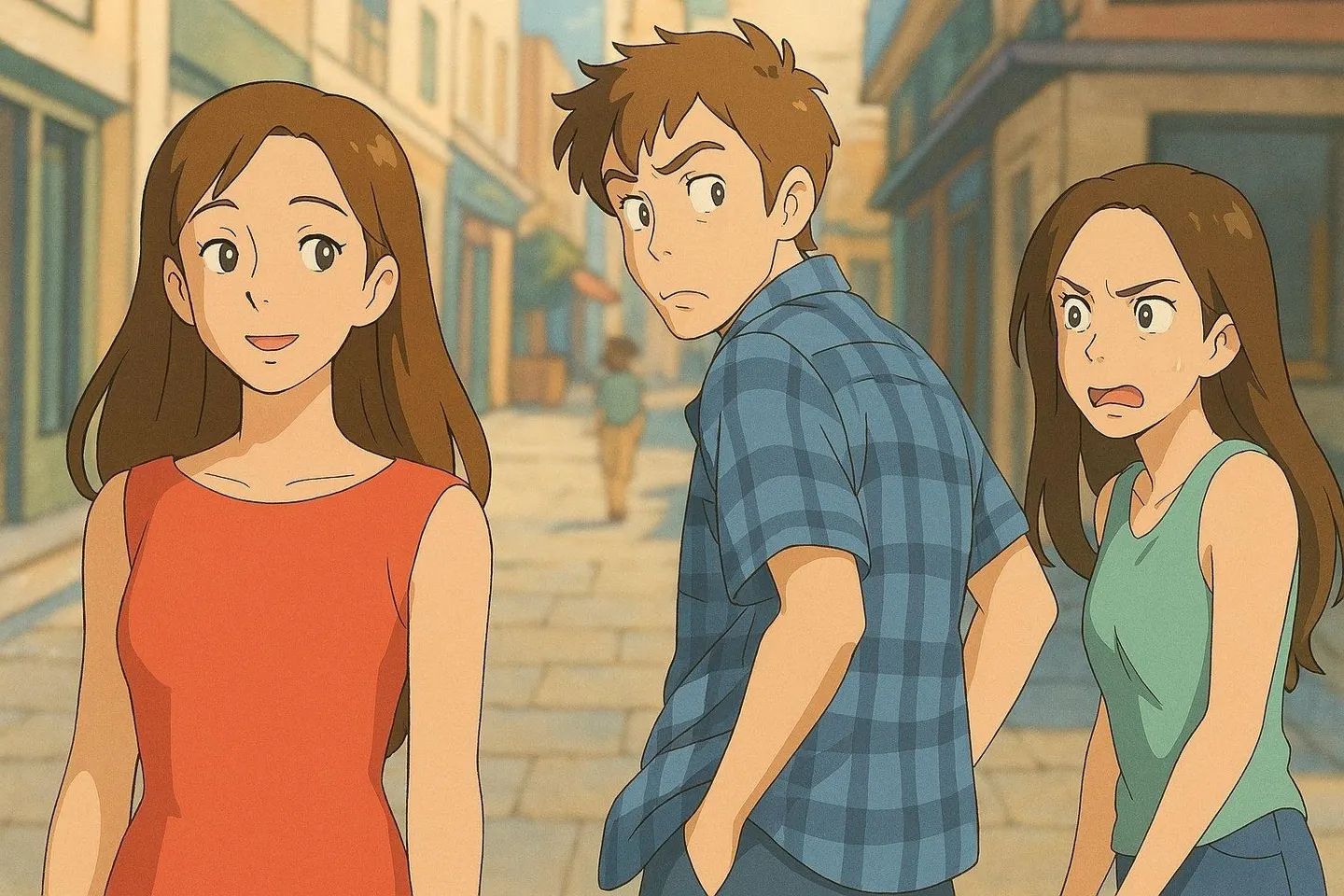

One of my favourite image-related anecdotes of the year occurred in March, when OpenAI released a new image model with a style emulation feature that took the internet by storm and pushed AI-image generation into the mainstream. Specifically, the storm swirled around the model’s ability to generate images in the style of beloved animation company Studio Ghibli. It allowed users to input an image, which the model then returned as a cute cartoon version in the style of Japanese animator and filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki’s whimsical films. The most interesting datum was that, in the week of its launch, 700 million images were produced, a significant amount of which were in the pseudo Studio Ghibli style. I want to pause here for effect because that number is absolutely insane: 700 million images. In comparison, in 2022 (according to Domo’s Data Never Sleeps report), all Instagram users grouped together produced just 665 million posts per week. We are being inundated with so-called images, at the exact moment that they are slowly dying and losing their power.

Images had a good run. For around 75,000 years, we used them to create representations of our physical world. Images were tools of ‘mimesis’ aiming to represent nature. In around 340–322 BCE, Aristotle wrote in De Memoria et Reminiscentia of images as a medium of recollection. However, he also warned us in De Insomniis, another short work in the collection Parva Naturalia, about the potential for the dream-image to mislead, because the dream-image can be indistinguishable from waking perception. The soul, deprived of corrective sensory input, accepts images as if they were real. Though he was writing specifically about sleep and dreams, Aristotle intuits what later philosophers will identify, which is that images possess phenomenological force independent of truth.

This concept was renewed by philosopher Vilém Flusser many years later in his book, Towards a Philosophy of Photography (1983). He wrote: ‘Essentially, this is a question of “amnesia”. Human beings forget they created the images in order to orientate themselves in the world.’ This amnesia is one of the effects of images, which (when maintained in controlled numbers) we have enjoyed and utilised to produce culture. When immersed in a film, we temporarily forget that what we are watching is fiction. When we encounter a striking image, like the one of the Buddhist monks standing on rubble from the earthquake in Myanmar in April, the apocalyptic images of the L.A. fires, or even the crowds almost cinematically placed around the casket of Pope Francis, we forget the framing, the choices the photographer made. Unfortunately, when images overtake reality, they stop representing reality; they stop serving as evidence. They change and are no longer guides to make sense of the world. Rather, they exist as independent entities.

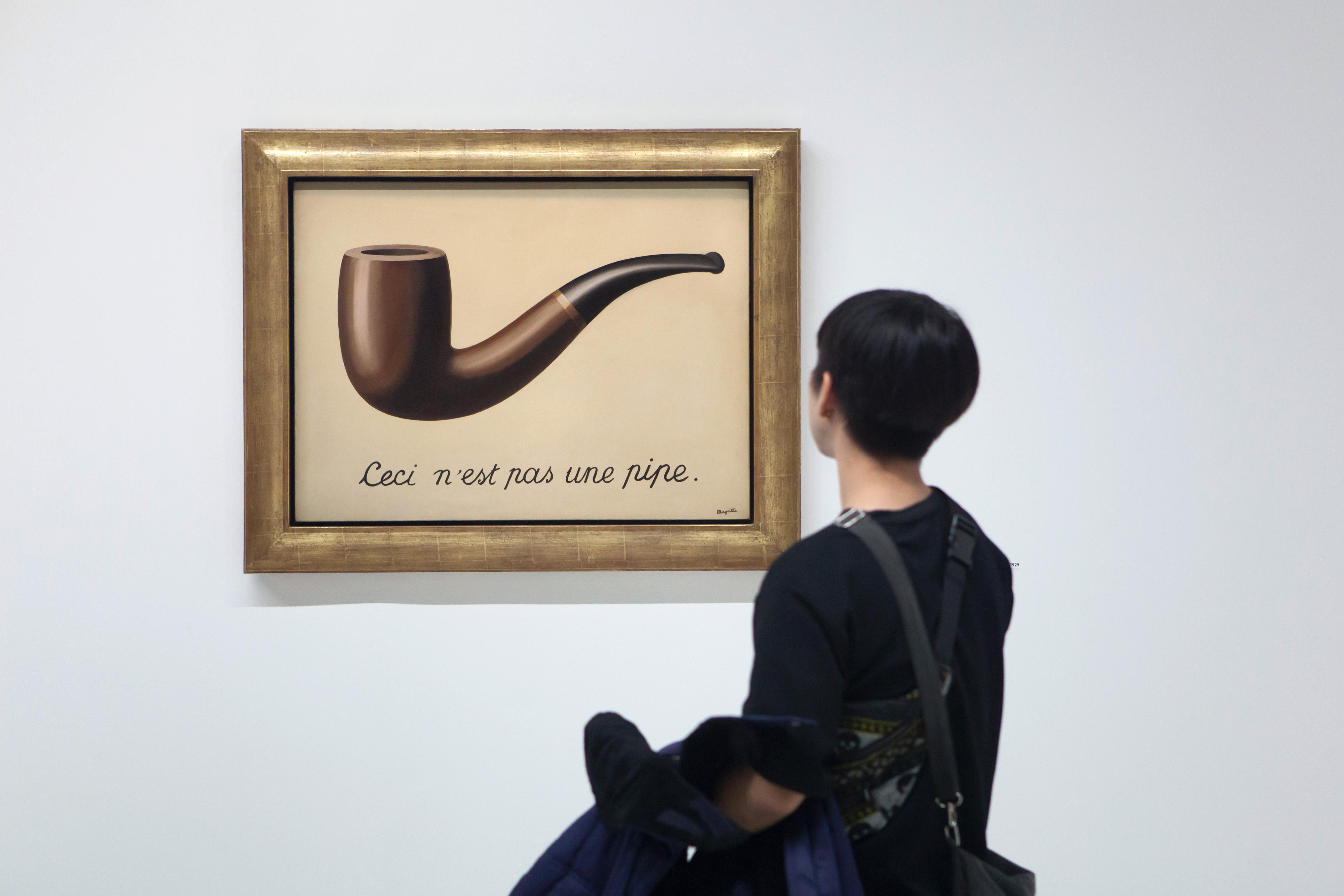

The death of the image was caused by two phenomena: the treachery of images and what I call ‘default fakeness’. In 2023, I wrote an essay called ‘The Treachery of Images’, which stated that the Image was entering a crisis—one being brought about by the advent of widely disseminated AI-generation technologies, specifically diffusion models, whose ability to produce realistic images was growing rapidly with time. The term ‘Treachery of Images’ comes from Surrealist Rene Magritte’s 1929 painting of the same name. The painting depicts a pipe juxtaposed with an inscription below: ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe.’ Or, in English, ‘This is not a pipe.’ This is the paradox of the image: it represents the thing but is not the thing.

This crisis is what happens when the image is free from authorship and relationship to reality, when it is fully emancipated and transformed into a new entity, closer to Aristotle’s concept of the dream-image, an image with no relation to the material world. Think of it this way: the AI-image represents a rupture in the role of images (something many artists and theorists have tried to grapple with this year, including Hito Steyerl in her recent book Medium Hot). This theory captures something materially observable: that once humanity acquired the capacity to produce images, it did not—and, most importantly, could not—stop. In this generated deluge, the world is submerged by dream-images.

The other phenomenon is ‘default fakeness’. It’s an epiphenomenon of the first. ‘Default fakeness’ describes an epistemological change or a change in how we acquire knowledge when faced with the preponderance of computer-generated images. Because of the uncertainty that these generated images’ presence causes, we enter a state of epistemological scepticism, whereby the entirety of the image corpus is now put into question. Every image encountered now is seen as ‘default fake’. Upon encountering an image on X or Instagram, like the false image of the Hollywood sign going up in flames during the L.A. fires, and discovering it to be AI, we start to assume that all images are generated or fake until proven otherwise. Instagram has even instated a tag for AI-generated images for clarity.

I have previously written about an upcoming decisive moment: the time when there will be more AI-generated images than human images. I called this the ‘pictorial flippening’. In retrospect, there was an error in my calculations of when this moment would occur. I underestimated the exponential character of image production once the technical threshold had been crossed. I predicted that there would be fewer human images than AI-images by 2044. I had assumed a bold growth rate of 50 percent in our AI-image production and still I underestimated our societal desire to produce new, fictional images. That estimate now appears overly conservative and wrong. Given the velocity and ease of contemporary AI-image generation, we have already met the threshold. The treachery of images accelerates itself and we are in the world of exponentials and not linearity: the easier images become to produce, the more images we produce, and the faster reality is submerged beneath their accumulation.

Wakes and dirges can be sombre affairs, but the death of the image need not be sad. When images lose their representational power, we awake from our 75,000-year-long sleep and must orient ourselves through the world with new tools. Faced with an avalanche of images, reality regains its lustre. Suddenly, the real matters again, because it is all we can trust. In that spirit, Broadway attendance for live theatre increased 15 percent this year and Lyas’ fashion show watch parties, where people gather at bars to look at runways together, took off, causing lines around the block in New York and Paris. Through our newfound scepticism, we learn to love our senses and mediate the world with the immediate. The image is dead. Long live the image. When the funerary veil is lifted, when the grief settles, reality looks oh so lovely. —[O]

No comments:

Post a Comment