How a Medieval Murder Map Helped Solve a 700-Year-Old London Cold Case

It all started as a Cambridge criminologist’s macabre hobby.

ON FRIDAY, MAY 3, 1337, Chaplain John Ford was strolling down the bustling market street of London Cheapside during golden hour—when three men assaulted him. As one man stabbed Ford in the throat with an 11-inch-long dagger, the other two slashed his stomach open. Ford was left to die in a puddle of blood under the arches of what once was Greyfriars Church as the assailants escaped. Among the crowds, a hatter, a rosary-maker, and a third man called for help.

When local officials filed a report detailing the murder, a mysterious “longstanding dispute” was mentioned alongside one name: the rich and famous Ela FitzPayne.

But what could the churchman possibly have done for the noblewoman to order the man’s murder in broad daylight on a crowded London street?

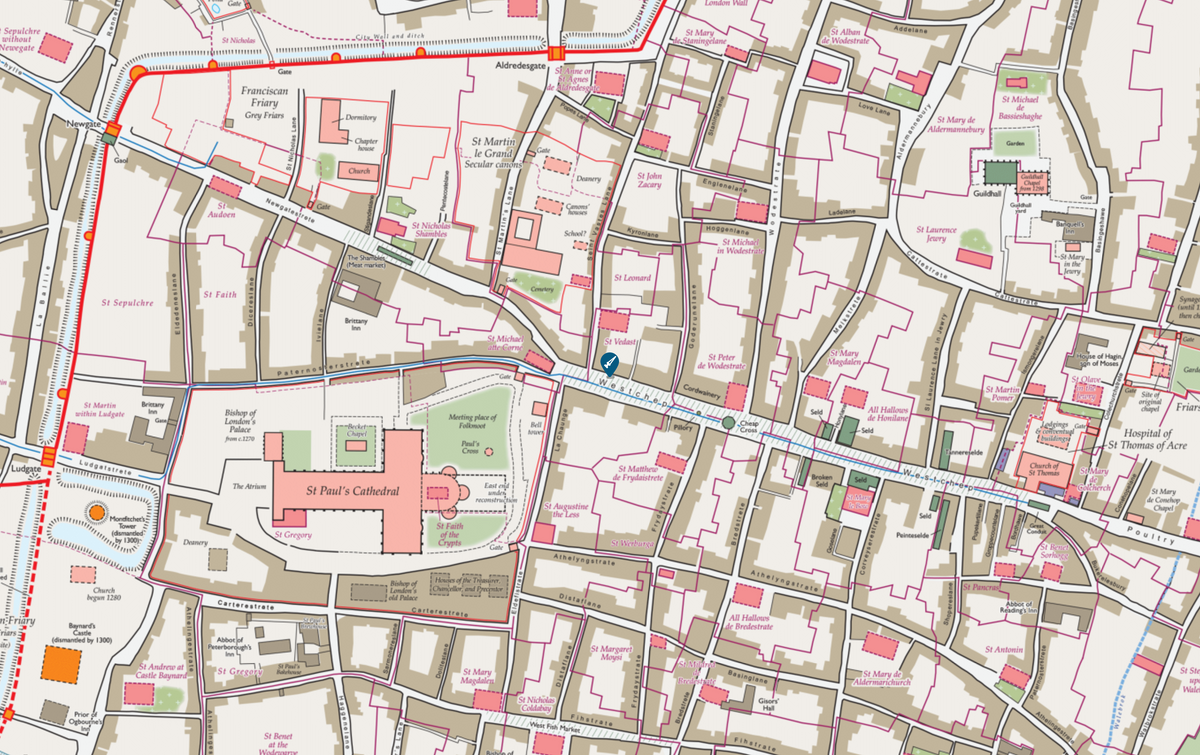

These are the kinds of questions that Manuel Eisner, the deputy director of the Cambridge Institute of Criminology, asks himself daily. In 2018, Eisner founded the Medieval Murder Maps—an interactive medieval murder map plotting the sudden deaths of thousands across the medieval towns of London, York, and Oxford. For Eisner, cracking 700-year-old cold cases, like the murder of John Ford, can provide an invaluable snapshot into medieval life, helping us understand the origins of the modern criminal justice system, what life was like for the past’s everyday people, and how crime patterns have, or haven’t, changed.

“I call it a distant mirror,” says Eisner. “You don’t just read it as violence. You have these little stories that are taking you on a time travel [adventure].”

Eisner, whose work has primarily focused on the when and where of contemporary crimes, started looking into mapping medieval crimes in 2012. For fun, he and his wife would stand at the kitchen table, and while she read out stories of 14th-century murders, he planted pins into an antique map of London of where they would have taken place.

For London-based crimes, the Eisners could refer to transcriptions and translations of the Coroners’ Roll, some of England’s earliest legal records. The rolls date back to the 14th century when a newly-appointed royal official, the “coroner,” would investigate any sudden or unnatural deaths: think murders, suicides, or accidents. The coroner would interview a “jury” of 12 to 50 people from the neighborhood about when and where the death happened, who died, what (if any) weapons were used—writing down their responses in the roll.

But few Coroners’ Rolls are complete, and even fewer have been studied and translated into something easily digestible today. Cambridge historian Stephanie Brown, who researches medieval crimes in Yorkshire, soon joined Eisner to help expand his maps, formalize the project, and add records from lesser-researched cities. Now Medieval Murder Maps is an interactive website where users can browse murders of 14th-century London, Oxford, and York.

Brown is a skilled paleographer and has helped the team decipher the mysterious, medieval penmanship of the Coroners’ Rolls—unlocking centuries of secrets. “You have these huge bits of parchment. Each page is probably about a meter long and half a meter wide, written on vellum, animal skin, and you need to be able to read this 14th-century handwriting,” says Brown of the Coroners’ Rolls.

Brown, who often visits the National Archives in London to touch the documents and “connect closer to the medieval people who would have been putting these documents together,” first transcribes the rolls, jotting down a legible version of the original Latin text. Then she translates the Latin into modern English.

Even armed with a translation, the rolls still hold mysteries for Eisner and Brown. Coroners often referenced places that no longer exist. Medieval England didn’t have postcodes or street numbers, and sometimes coroners just noted details such as “where widow Severless was living.” So the historians often have to cross-reference their findings with ancient financial records or housing documents too.

“Honestly, having looked at these records, I’m shocked that [the Cambridge team] were able to do as good of a job as they did. Kudos to them,” says Sara Butler, director of the Center for Historical Research at Ohio State University, who is not involved in the project. “Having these historic maps available so we can go in and explore is awesome. It’s really exciting.”

Thanks to these maps, it’s easier to spot trends in crime throughout history. Eisner and Brown recently published statistics detailing how Oxford can be crowned a medieval murder capital due to its population of rowdy youths. In the 14th century, the per capita homicide rate in Oxford was up to five times higher than in major cities such as London or York, and 75% of the perpetrators were students between the ages of 14 and 21

“The Oxford stats are really fascinating. It’s not just because they’re students—although the youth, the masculinity, all of that doesn’t help,” says Butler. Within the university, students were often split into individual colleges according to their nationality, so a lot of this crime represents rivalries between those different groups, “playing out in a gang warfare kind of way,” says Butler.

This is just one way Eisner’s murder maps help scholars understand the social, political, economic, and legal realities of the medieval world. This was a time of transition, especially for law enforcement.

Before the 14th century, many violent crimes were dealt with privately, without a formal trial, says Eisner. But after 1330, the state started to more regularly intervene in their towns’s justice. New laws mandated that all prisoners were tried and the jail emptied three times a year (to dole out justice consistently). Convicted murderers were to be sentenced to death, and sometimes that wasn’t even the end of their punishment.

Still, most criminals fled the realm and sought sanctuary elsewhere, and records show that only five to 10 percent of people who were finally tried for homicide were hung. Most were either acquitted, transferred indefinitely to a church prison, granted a royal pardon, or died before trial because of the poor conditions of medieval prisons.

“I’m fascinated by the way people at the time tried to find the truth,” says Eisner. During the 14th century, “there are certain rules about what to do and how to do things. All of this is being invented in that period.” The Coroners’ Rolls, for instance, marked one of the first times in history that government officials were making formal investigations into everyday murders and sudden deaths. The medieval criminal justice system was imperfect, says Eisner, but you can see it developing throughout the 14th century.

Crucially, the Coroners’ Rolls and other criminal records tell the stories of ordinary people. “These are people like you and me: ordinary, run of the mill; not the great and the good, not the elite, not the rich,” says Brown. For many people mentioned in the rolls, it’s the only time, throughout all of history, that their name was ever written down. Such was probably the case for Hugh Colne, John Strong, and John Tindale—three of the men enrolled for the hit job on John Ford that Friday at sunset. “So it’s about understanding our history and our heritage,” says Brown.

Eisner’s maps also shed light on violent crime patterns—some of which haven’t changed much in 700 years. For instance, the percentage of female suspects charged or convicted of murder in medieval London and York is broadly in line with statistics from the 21st century, says Brown—only around a quarter of crimes. When women were suspected of a crime, they often, at least according to surviving records, didn’t act alone. They’d be charged alongside a male relative or their husband as an accomplice or a behind-the-scenes orchestrator.

“Are women more likely to seek support?” asks Brown. “Have women internalized a traditional gender role and put themselves more passively? Or is this the male jury members underestimating women?” Browns says many of these questions are up for debate.

When sleuthing for more information on noblewoman FitzPayne, the team came across a mention of her in a letter from the Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon Metham, to the Bishop of Winchester dated January 29, 1332. The letter described how FitzPayne was convicted of adultery. (She had slept “with knights and others, single and married, and even with clerics in holy orders,” the letter read.) Sentenced to a punishment of public humiliation, FitzPayne had to walk barefoot from the western entrance of Salisbury Cathedral to the high altar carrying a large, lighted candle as an offering every day for seven years. She was also prohibited from wearing gems, silver, gold, or any makeup. Needless to say, she had held a grudge.

Only one other person was mentioned by name in the letter—a former lover who’d go unpunished for their relationship, a man who maybe even told the Archbishop about FitzPayne’s acts of adultery. Back then, just like today, humiliation and revenge can be strong motives for murdering somebody in broad daylight, says Eisner. Indeed, this person’s name was John Ford.

© 2024 Atlas Obscura. All rights reserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment