|

Looted art |

|

Martin Bailey |

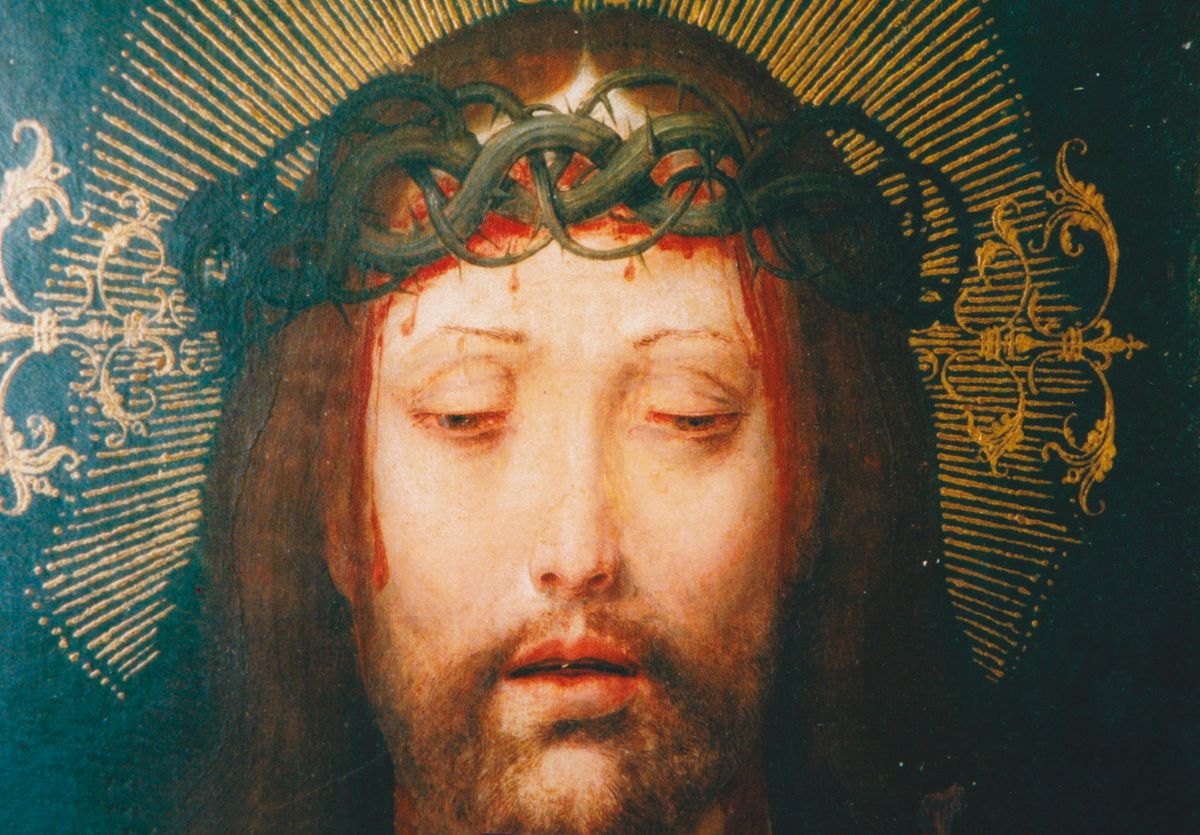

Exclusive: first colour photographs shed fresh light on Ethiopia's most treasured icon and its looting by an agent of the British Museum

An Art Newspaper investigation uncovers new details on the infamous seizure in 1868 by Richard Holmes of a 500-year-old painting of Christ, the Kwer’ata Re’esu, which never reached the London institution

The colour image of the Kwer’ata Re’esu (detail above, full image below) can be seen for the first time after The Art Newspaper tracked it down in Portugal, in the possession of an heir of Luiz Reis Santos, who bought the painting in 1950Image may be reproduced, with the credit: Martin Bailey (photograph), The Art Newspaper

Contact: info@theartnewspaper.com

Among the greatest Ethiopian cultural losses suffered at the battle of Maqdala in 1868 was a remarkable 500-year-old icon of the suffering Christ. It was looted by a British Museum agent, Richard Holmes, who had been sent to bring back manuscripts and antiquities from Ethiopia. On his return he failed to hand over the masterpiece to the museum, instead secretly keeping the painting, so the museum had no direct involvement in handling it. The heir of Holmes subsequently sold the picture at Christie’s in 1917.

The Art Newspaper tracked down the painting, known as the Kwer’ata Re’esu, in 1998, when it was in a Portuguese bank vault (at that point we reproduced the picture in black and white). This was probably the only occasion when the icon has been seen by anyone in living memory outside the owner’s immediate circle.

We can now finally name the owner, who personally showed me the work: the Coimbra-based Isabel Reis Santos, heir of the Portuguese art historian Luiz Reis Santos. When I travelled to see the Kwer’ata Re’esu, it was boxed and still in the wooden crate in which it had been shipped from London. Kept in a bank vault, the painting was wrapped in a 20 April 1950 copy of the London Evening News. In 1998 The Art Newspaper did not identify the owner, but does so now since she has been named in the official Portuguese government gazette.

The Kwer’ata Re’esu has an astonishing cross-cultural story. Painted in Europe in about 1520, either in Iberia or Flanders, it was probably sent soon afterwards to Ethiopia, where a religious inscription was added in Ge’ez, the ancient liturgical language. There it became the holy icon of successive Ethiopian emperors in what has been a Christian land since the fourth century. Nobles swore allegiance beneath the painting and on several occasions it was carried into battle when Christian forces were fighting Muslims. Although very little known outside Ethiopia, it is highly important in both historical and art historical terms.

The painting itself is in good condition given its age and its patchy history of storage and movementImage may be reproduced, with the credit: Martin Bailey (photograph), The Art Newspaper

Contact: info@theartnewspaper.com

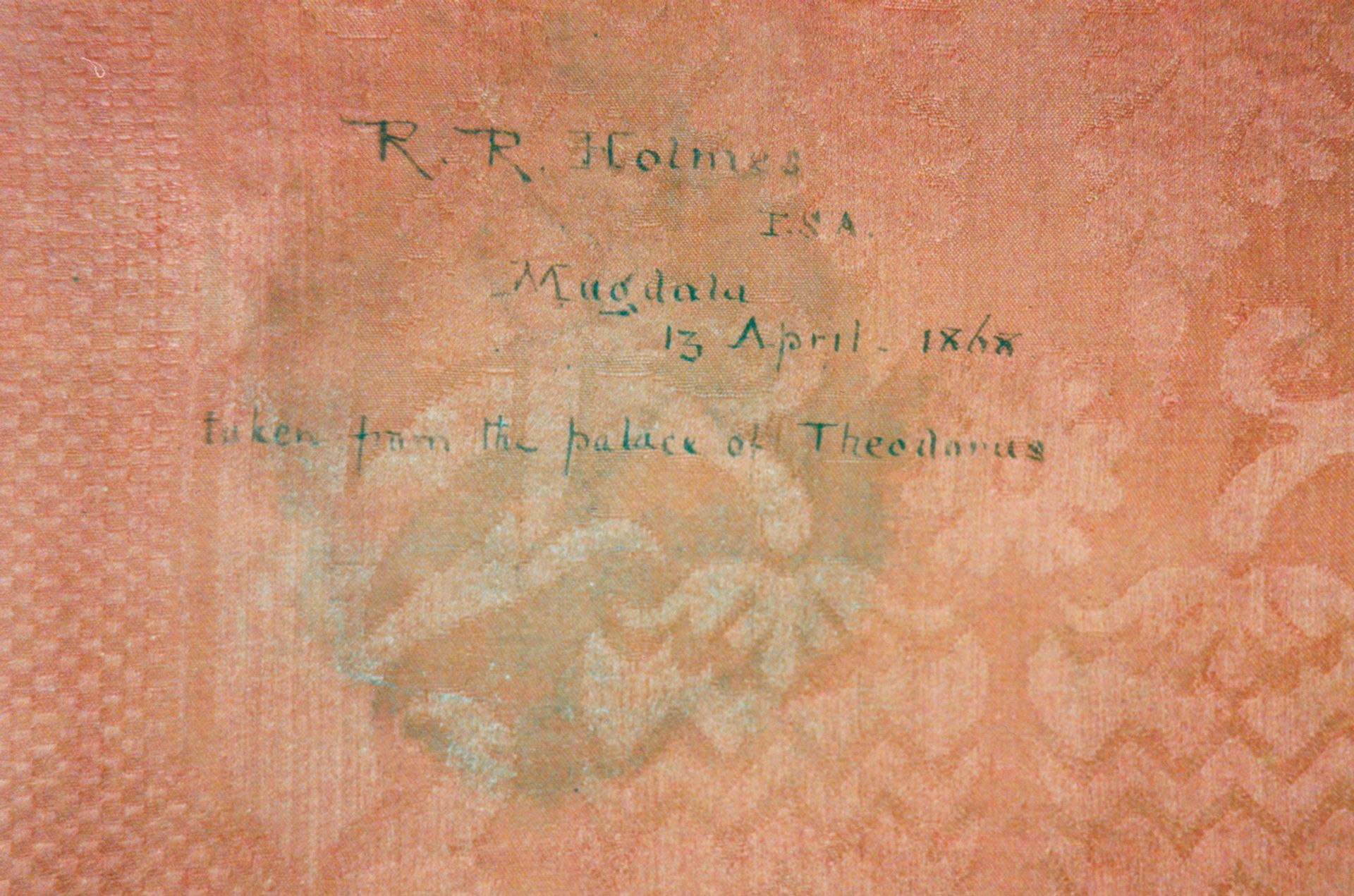

Painted on an oak panel (33cm x 25cm), the holy icon has survived in its original inner frame, which is of early 16th-century Flemish style, with a larger and more modern outer frame. On turning over the frame, I found that the reverse was covered with red silk damask with a stylised pomegranate pattern. Last month the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) textile curator Silvija Banić identified the silk from my photograph as Italian, dating from very roughly 1600 and possibly woven in Florence. How the silk reached Ethiopia remains unknown.

On the silk I found an unrecorded inked inscription in the handwriting of Holmes: “R.R. Holmes/ FSA [Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries]/ Magdala/13 April 1868/ taken from the palace of Theodorus.” Dated the day of the battle, this was conclusive proof that the painting had been looted.

The reverse of the Kwer’ata Re’esu is covered in red silk damask, which a textile expert has identified as being Italian, around 1600. It bears Holmes’s writing saying “taken from the palace of Theodorus”Image may be reproduced, with the credit: Martin Bailey (photograph), The Art Newspaper

Contact: info@theartnewspaper.com

Considering its astonishingly chequered history, the 500-year-old painting has miraculously survived in good condition.

The mystery artist

The Kwer’ata Re’esu is a representation of the blessing Christ, with a crown of thorns and with dripping blood. It was painted by a European artist in the Flemish style—or possibly even by a Portuguese painter working in Ethiopia. Based on the poor and only extant 1905 black-and-white photograph, art historians have made provisional attempts to attribute it to a named painter.

The Art Newspaper hopes that this new colour image will make it possible for specialists to make a secure attribution. Previous attributions include the Flemish artists Quentin Matsys, Adriaen Ysenbrandt, Aelbrecht Bouts and a pupil of Hans Memling; the Portuguese artists Lázaro de Andrade and Jorge Afonso; and the Spanish artist Bartolomé Bermejo.

Mystery surrounds the picture’s arrival in Ethiopia. It may have been brought by Jesuit missionaries or presented to an Ethiopian diplomatic mission visiting Portugal. By the early 17th century the inscription (now very faded) was added to the top left of the painting in Ge’ez: “How they struck the head of Our Lord”. This original Catholic image of Christ was worshipped by Orthodox Ethiopians.

The Kwer’ata Re’esu became increasingly revered and by 1700 a special tent protected it in the emperor’s camp. When a fire once swept through his camp, it subsided as soon as it reached the tent, giving the icon a reputation for performing miracles. In 1744 the painting was captured by Sudanese Muslims, but was later returned for a ransom.

James Bruce, a British visitor to Ethiopia in 1768-73, recorded that what he termed the “quarat rasou” had been “only a little profaned by the bloody hands of the Moors” and “all Gondar was drunk with joy” on its return. Bruce described the painting as “a relique of great importance… said to have been painted by St Luke [the patron saint of artists]”.

The Kwer’ata Re’esu’s importance can be gauged by the fact that from the early 1700s it was very widely copied in Ethiopian manuscripts and religious paintings—right up until today. In many of the early copies, the image is surrounded by a red border, suggesting that it may have already been encased in the Italian silk.

Deathbed drawing

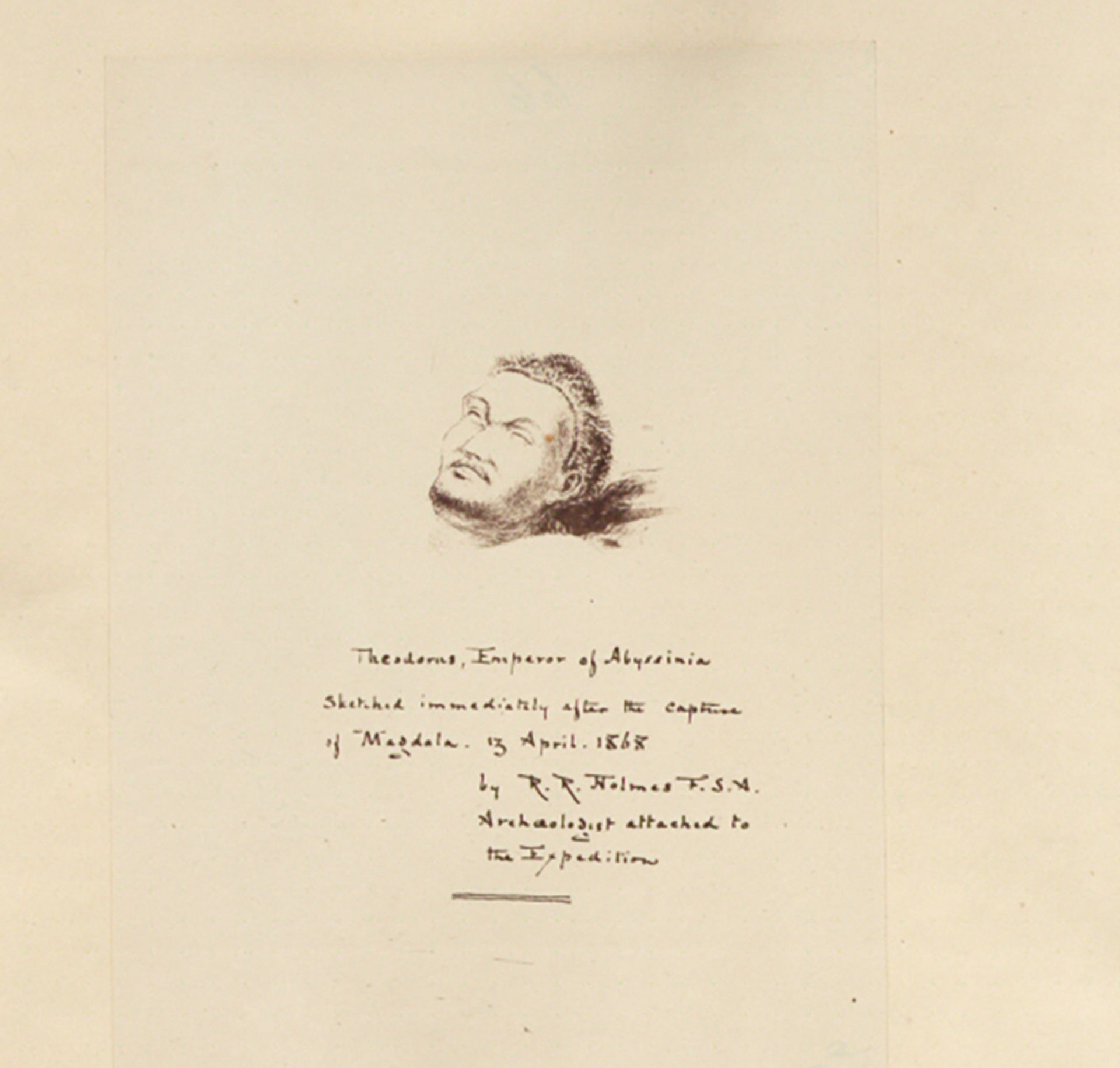

Holmes played a most unseemly role in the story. After being dispatched by the British Museum as its agent he arrived on 13 April 1868 at the emperor’s bedside at Maqdala (Magdala) just minutes after Tewodros II (Theodore) had committed suicide, shooting himself with a pistol that had been given to him in better times by Queen Victoria. The emperor lay on his deathbed, his body still warm.

A deathbed sketch of Tewodros by Holmes inscribed “Theodorus, Emperor of Abyssinia, sketched immediately after the capture of Maqdala, 13 April 1868 by R.R. Holmes F.S.A., Archaeologist attached to the Expedition”The National Archives

The Kwer’ata Re’esu was apparently hanging just above the emperor’s bed. Holmes immediately grabbed it before it could be looted by one of the British troops. At this point he must have been mystified as to why what appeared to be a Flemish painting had ended up in this remote Ethiopian mountainside location. Having seized the icon, Holmes calmly sketched a deathbed portrait of the emperor.

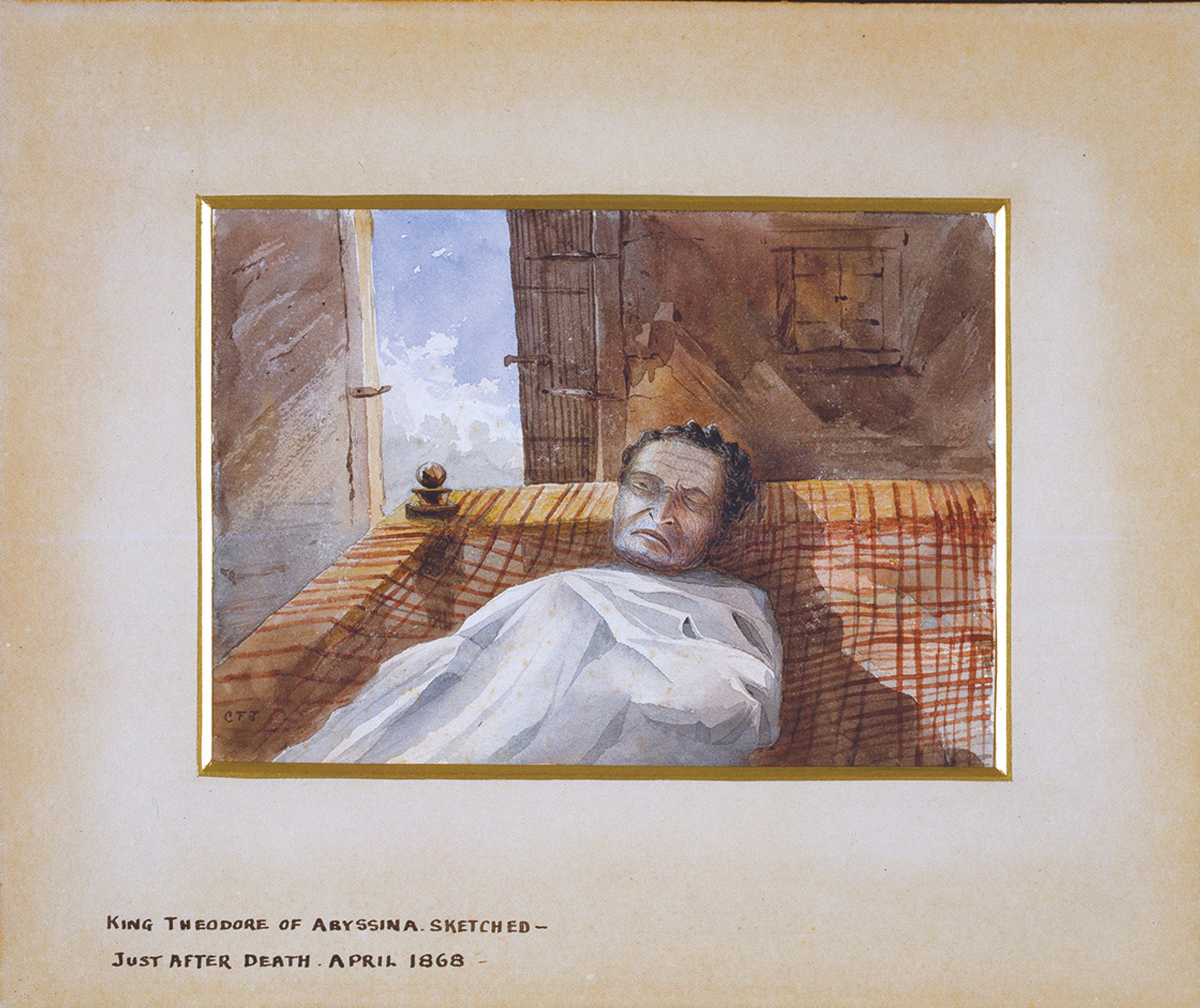

There is another portrait that adds to the story. Frank James, a British soldier and amateur artist, made a deathbed watercolour, which includes a box-like structure hanging on the wall above the bed. Its proportions and apparent size suggest that it might well have served as a protective cover for the precious Kwer’ata Re’esu.

In addition to Holmes’s sketch, this watercolour of the emperor by Frank James, a British Army lieutenant, may show the protected icon on the wall behind him, in the upper-right corner of the sketchNational Army Museum

A few days later Holmes set off for London with his booty: dozens of antiquities—and the Kwer’ata Re’esu, which he kept for himself. Two years later he was appointed by Queen Victoria as her royal librarian.

The Kwer’ata Re’esu remained a secret until 1905, when the May issue of The Burlington Magazine carried a short anonymous article on “A Flemish picture from Abyssinia”, probably written either by Holmes (who was on the magazine’s committee) or his nephew Charles John Holmes (its co-editor).

Holmes died in 1911. Six years later the Kwer’ata Re’esu briefly surfaced at Christie’s. It was not identified as having come from Ethiopia, but as “Bruges School”, and it sold for £420, going to a London buyer, Martin Reid. In 1950 Reid’s heir sold the picture, again at Christie’s, this time as painted by Ysenbrandt.

The highest bid was £131, but this was below the reserve, and the painting was later sold privately to Luis Reis Santos, a Portuguese art historian who had himself published an article on the Kwer’ata Re’esu in the July 1941 issue of The Burlington Magazine, arguing that it was not Flemish, but instead by a Portuguese painter. The painting later passed to his widow, Isabel.

An export ban

To continue the story, on 16 February 2002 the Portuguese ministry of culture published an order in the Diário da República gazette. This required that the painting should not be exported without permission.

The picture was then described as “possibly Portuguese-Flemish”, attributed to the Portuguese artists Andrade or Afonso. There was no mention of its Ethiopian origins or its title, the Kwer’ata Re’esu. This meant that it escaped the attention of Ethiopians and those interested in Ethiopian culture.

The gazette entry has finally been spotted by Andrew Heavens, who recorded it in his book The Prince and the Plunder (History Press, 2023), where the 1905 black-and-white photograph is reproduced. Heavens points out that the Kwer’ata Re’esu can “no longer be moved out of the country without the specific authorisation of the Portuguese Ministry of Culture”.

Since our 1998 article numerous attempts have been made to track down the Kwer’ata Re’esu in order to seek its restitution to Ethiopia. In 2000 the British Ambassador in Addis Ababa privately revived the idea of trying to return the Kwer’ata Re’esu, but this never materialised. Although the location of the Kwer’ata Re’esu is now public knowledge, restitution would require the approval of the Portuguese government.

In a separate development, the Scheherazade Foundation, led by Tahir Shah, has been campaigning for the restitution of Maqdala treasures. On 21 September it arranged the return of a sacred tablet and a lock of hair from Prince Alemayehu, the son of Tewodros. The two objects are from separate private collections.

Shah now wants the Kwer’ata Re’esu to be returned to Ethiopia: “Pilfered by British forces at Maqdala, it was acquired by Richard Holmes, the British Museum’s man on the scene. It’s just a matter of time before it arrives back in Ethiopia, with jubilant celebration.”

No comments:

Post a Comment