Hy Mariampolski

From the Roxyettes

to the Rockettes

The Conclusion of the Movie Palace Movement

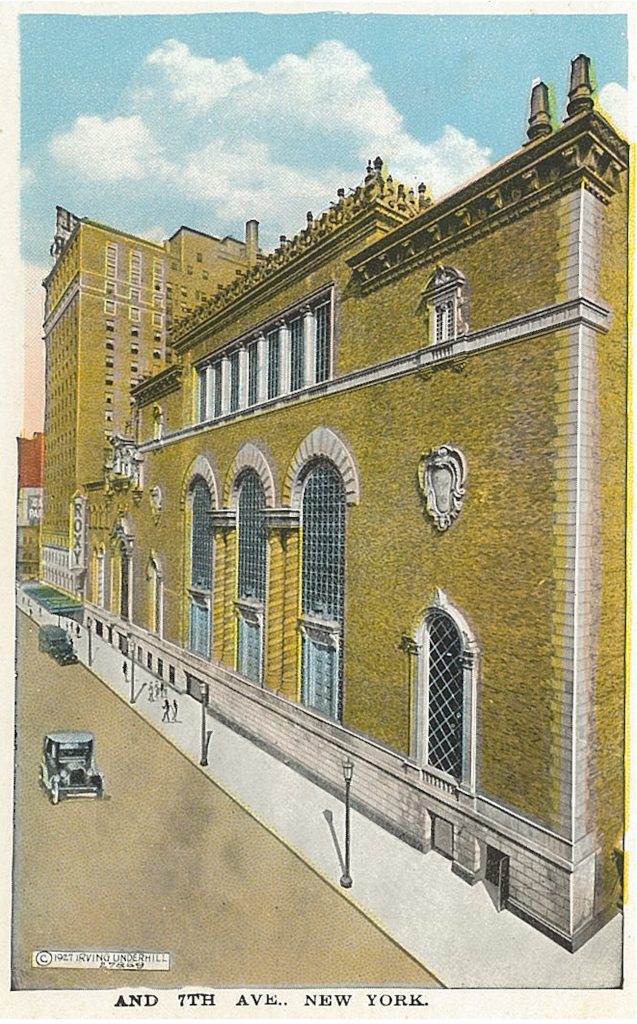

The largest movie theater ever built, the 5,920-seat Roxy Theatre opened in 1927 at 153 50th Street between 6th and 7th Avenues just outside of Times Square. Conceived by film producer Herbert Lubin and intended as a swan song for theater production innovator Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel – who started simplifying the spelling of his name. Rothafel was brought in for creative staging and for attaching his nickname to the brand in exchange for buckets of cash and a share of the gate.

At its most ambitious, this was intended to be a six-theater chain, however, after the Roxy, only the Beacon Theatre (originally called the Roxy Midway) was built, also designed by architect Walter Ahlschlager as a 2,894-seat “miniature” of the Roxy on Manhattan’s Upper West Side at Broadway and 74th-75th Streets. Despite its erratic history as a venue for classical concerts, dance, feature and second-run films, rock music emporium and event space, the Beacon is still kicking. It reopened recently after a brief closure during the Covid pandemic.

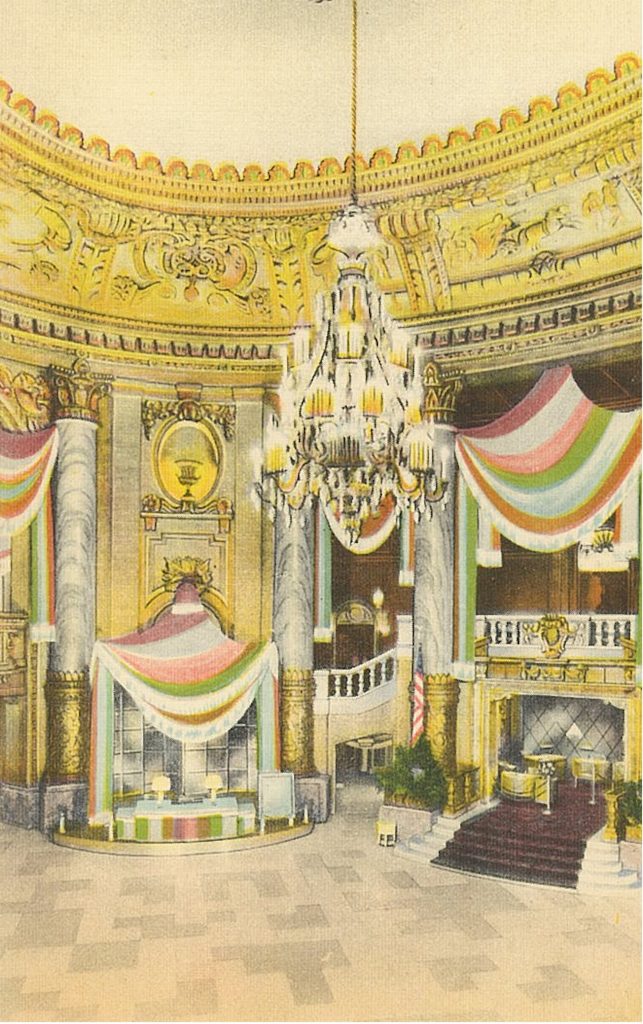

The adjective most often applied to the Roxy from its earliest days was “lavish.” This idea is clear from its main promotional postcard, whose ethereal coloring and staging evokes the “Cathedral of the Motion Picture” it was intended to become, a contrast to its terrestrial street image. Connected by an entryway on 7th Avenue through the hotel next door (originally the Manger, later the Taft, today the Michelangelo,) the architects aimed to provide a sense of arrival into a space extravagantly decorated with unique carpeting and tapestries.

Nothing “lavish” happens without a bountiful budget. Eventually, movie producer and theater owner William Fox was brought in for a controlling interest and to help underwrite the cost which climbed to $12 million. For that money, the Roxy installed the world’s largest oval rug for its Grand Foyer, its own separate pipe organ and a host of amenities for its performers and staff – from elaborate dressing rooms all the way down to an infirmary, cafeteria, gym, nap room, and library. Courteous service to patrons was essential to the Roxy’s formula and this was delivered by a platoon of uniformed hosts operating with near military precision.

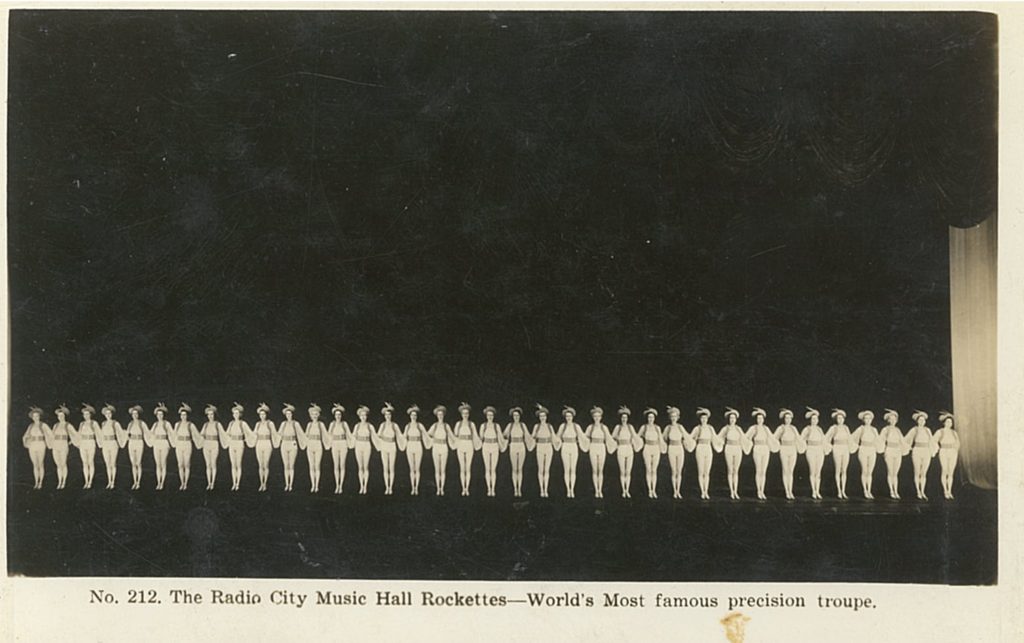

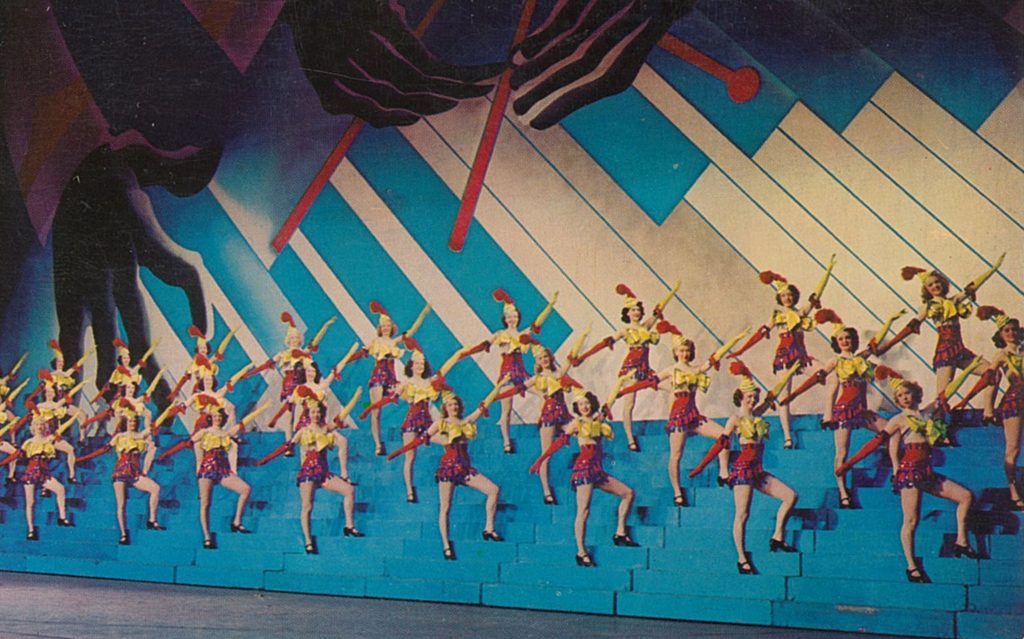

In addition to first-run Hollywood hits, the theater delivered a floor show dominated by a 110-member symphony orchestra, the organ, a men’s chorus and the precision dancing troupe, the “Roxyettes,” promoted via attractive brightly colored linen postcards with a textured feel that recalled canvas. A weekly radio program emanated from the theater’s own studio each week on the NBC network hosted by Roxy himself and gave the theater a national presence. It was a shame when the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash spoiled all this lovely extravagance.

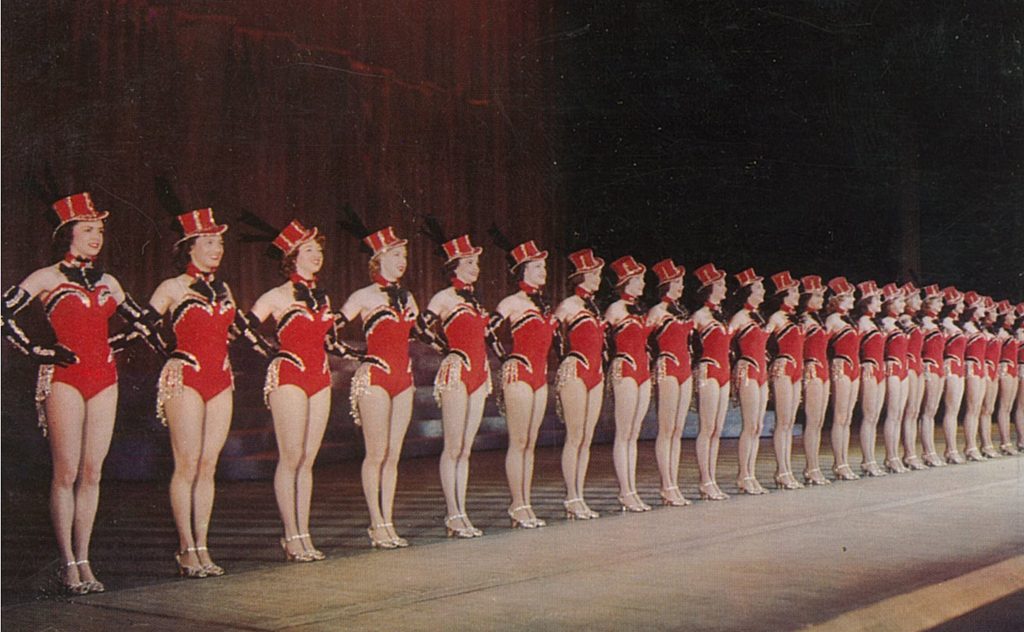

Suddenly, the Fox Film Corporation began suffering financial losses and was forced to start showing inferior films in a menacingly competitive market. Furthermore, Rockefeller Center, located just a little more than a block away, began making waves. Within this confusion of disappointments and hopes, S. L. Rothafel did the unanticipated. Described by theater critic Brooks Atkinson as “a humorless showman with the vision of a demented prophet and supreme self-confidence,” Roxy the guru jumped ship. He signed up with the Rockefellers’ latest endeavor Radio City Music Hall, expected to become a key enterprise within the new Rockefeller Center. Most of Roxy’s leadership and creative personnel went along with him, including the Roxyettes who were rebranded as the “Rockettes.” Interestingly, the precision dancers turned out to become the most beloved and enduring symbol of Radio City Music Hall, succeeding through today.

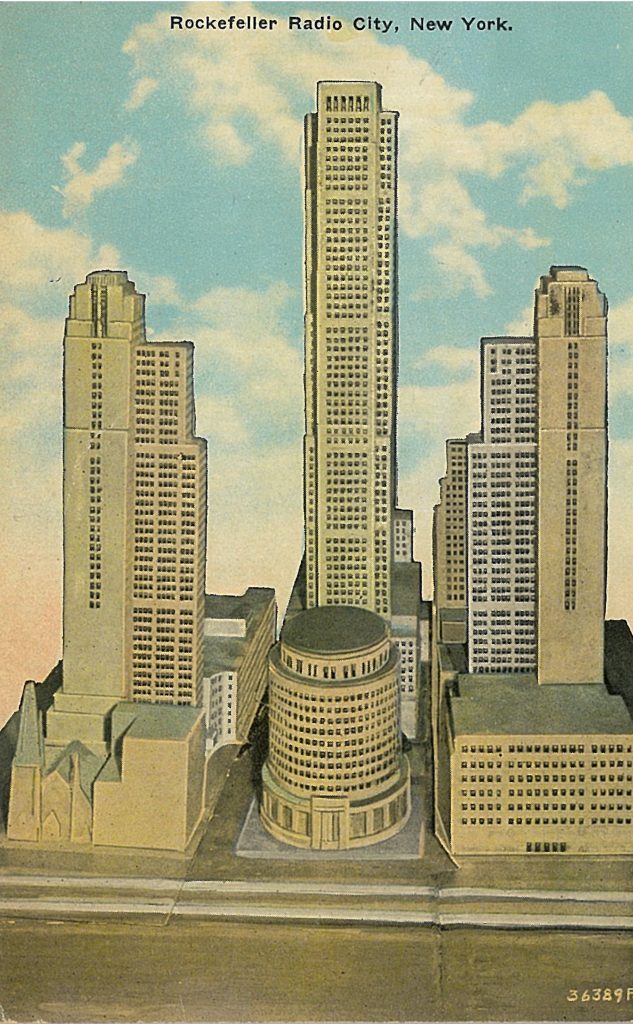

Attempting to meet the challenges of the Depression through investment and economic development, the Rockefellers had intended from the start to incorporate theaters into their massive multifunctional office environment, as these early postcard depictions of the Center’s plans illustrate. Until relatively late in the process, the main theater was intended as a new home for the Metropolitan Opera.

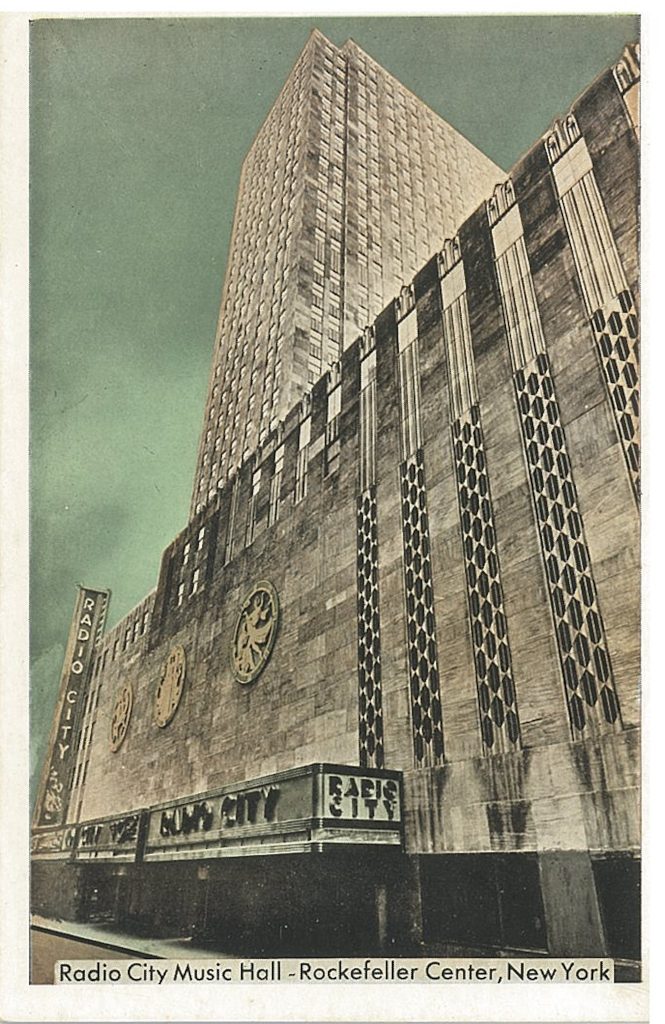

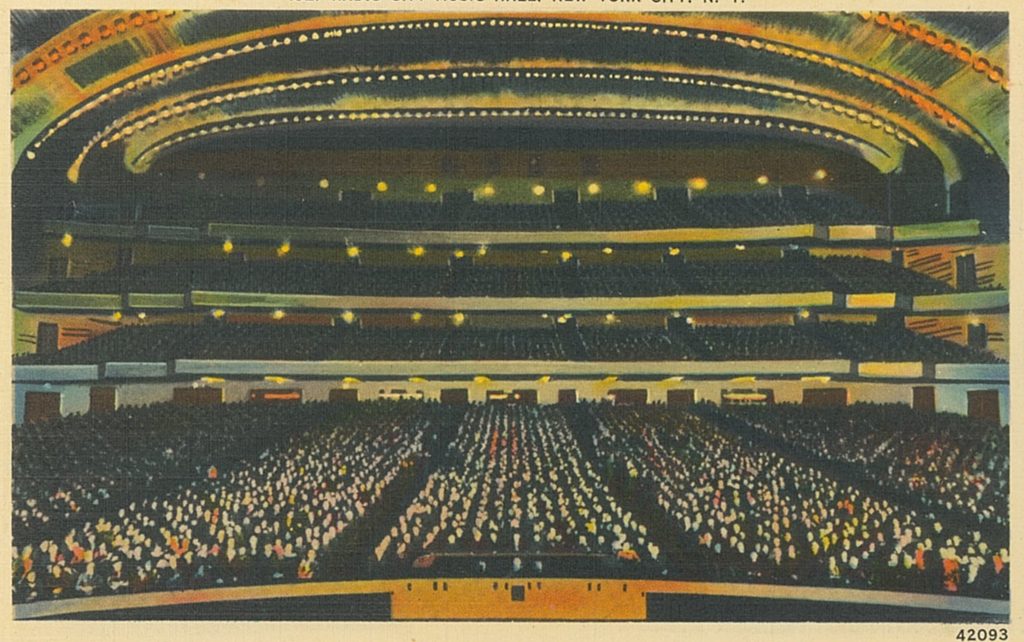

After the opera house concept evaporated, no one was certain what format the new theaters would take. By opening day December 27, 1932, the name Radio City became connected to the brand – honoring the Radio Corporation of America, one of the complex’s early tenants. A decision was made to call the theater a “music hall,” reflecting the vaudeville tradition of variety acts that the new venue was going to showcase.

Unfortunately, the opening night performance turned out to be a dud. Despite featuring vaudeville-style acts like Ray Bolger, The Mirthquakers, Martha Graham and the Tuskegee Choir, the show lasted past two in the morning and caused a walkout by major patrons. Rothafel suffered a heart attack in the confusion. It took Radio City Music Hall two weeks to decide on a format they took straight from the Roxy Theater – feature films alongside a multi-talented floor show.

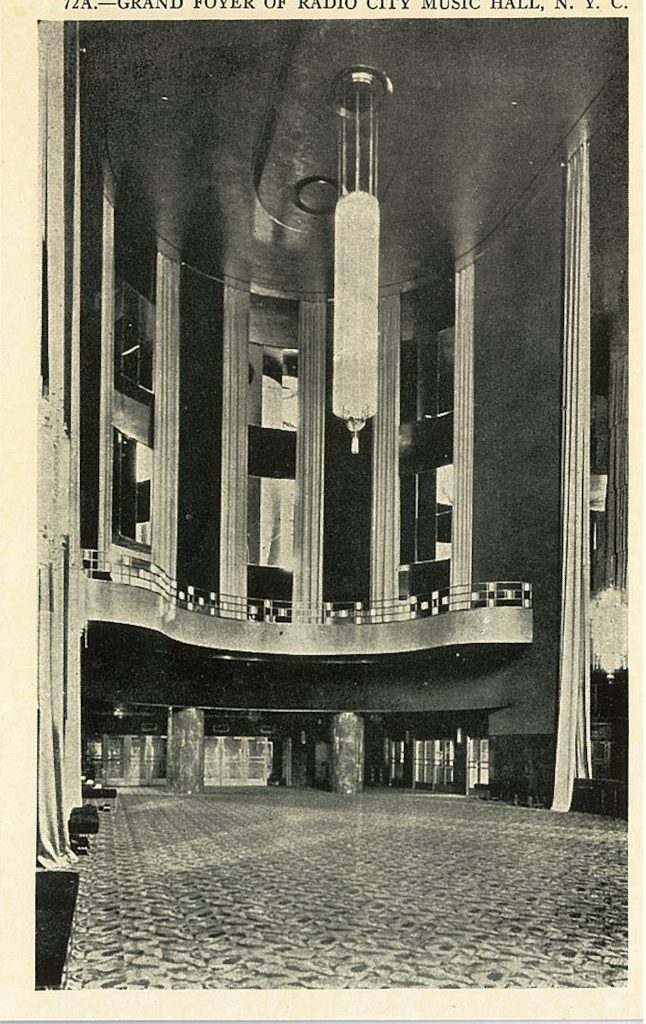

A postcard published to promote the new format shows the Corps de Ballet and the World’s Largest Theater Orchestra – taken straight from the Roxy. The Grand Lounge and Grand Foyer, also lifted from the Roxy, were prominent features of the new movie palace. Designed by Edward Durrell Stone with interiors by Donald Deskey in the Art Deco style, the theater was built with seating for 6,200 enabling its promoters to boast that it was larger than its predecessor.

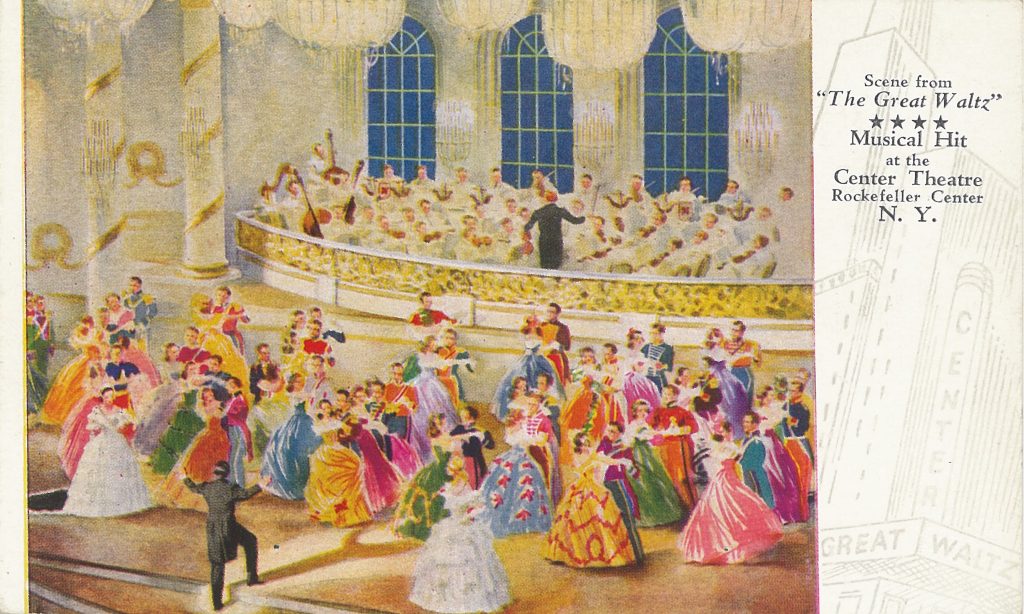

Radio City’s second theater did not have a long life although its struggles were very compelling. Intended as a new “legitimate” theater specializing in light opera and musicals, the Center Theatre (also called the RKO Roxy until its rights to the name were challenged) did not go far beyond a season of “The Great Waltz.” The Center tried other forms of programming from first-run movie theater to television studio – including broadcasts of the early comedy classic Your Show of Shows starring Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca – but just could not make it work. In 1954, it became the first and only section of Rockefeller Center to be torn down.

The Roxy soldiered on despite having its initial glow of optimism tarnished. The film products of the expanded 20th Century Fox improved under new leadership and the theater embraced the wide-screen trend, allowing it to overtake some of the stage space originally intended for the gigantic orchestra. The Roxy also shifted much of its live performances to ice shows, featuring such stars as Norwegian Olympic Champion Sonja Henie. Despite premieres of epic films like The Robe, the Roxy eventually lost steam. The beautiful cinematic cathedral faced the wrecker’s ball in 1960 and was replaced by an undistinguished office tower.

The program inherited by Radio City Music Hall – a movie palace showing performances in a film and stage-spectacle format became the major draw. The theater hosted many movie premieres offered by the increasingly creative RKO-Radio Studios and by a new entrant in the sphere of creative filmmaking, The Walt Disney Studios. Important films like King Kong (1937,) Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961,) To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) and Mary Poppins (1964) numbered among the openings at Radio City Music Hall from the 1930s through the 1960s. The 1937 premiere of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs marked the release of the first full-length animated feature.

The format lasted into the 1970s when declining patronage nearly drove the Radio City Music Hall to bankruptcy. However, enhanced by its over-scaled stage, curved proscenium and amphitheater-like seating, Radio City Music Hall eventually became synonymous with its principal attraction, The Rockettes. The abundance of postcards across time periods depicting the troupe could hardly do justice to the thundering hoofs clanking against the hardwood floors and their marvelous precision movements.

Buffeted by contention and controversy, the Radio City Music Hall was declared a New York City landmark in 1978 which protected it from being torn down. The venue was restored and allowed to remain open, but it had to pay a price. The theater was forced to abandon its movie palace model of feature films alongside live performances because it was no longer financially feasible – marking the definitive end of the movie palace era. Instead, especially following a renovation in 1999, the theater became a location for concerts, featuring everyone from The Grateful Dead, Liberace, Tony Bennett, Lady Gaga, Adele, and Britney Spears and exceptional events like award presentations including the Tony Awards, the Grammy Awards, and the MTV Video Music Awards.

Once a year as the wintry chill descends on New York City, the glorious days of the past, now a 90-year-old tradition, are recalled in its Radio City Christmas Spectacular, a seasonal musical performance, complete with the beloved Rockettes.

Copyright © 2023 Postcard History LLC