April 9, 2023

George Miller

Some Thoughts about

Early Postcard Collectors

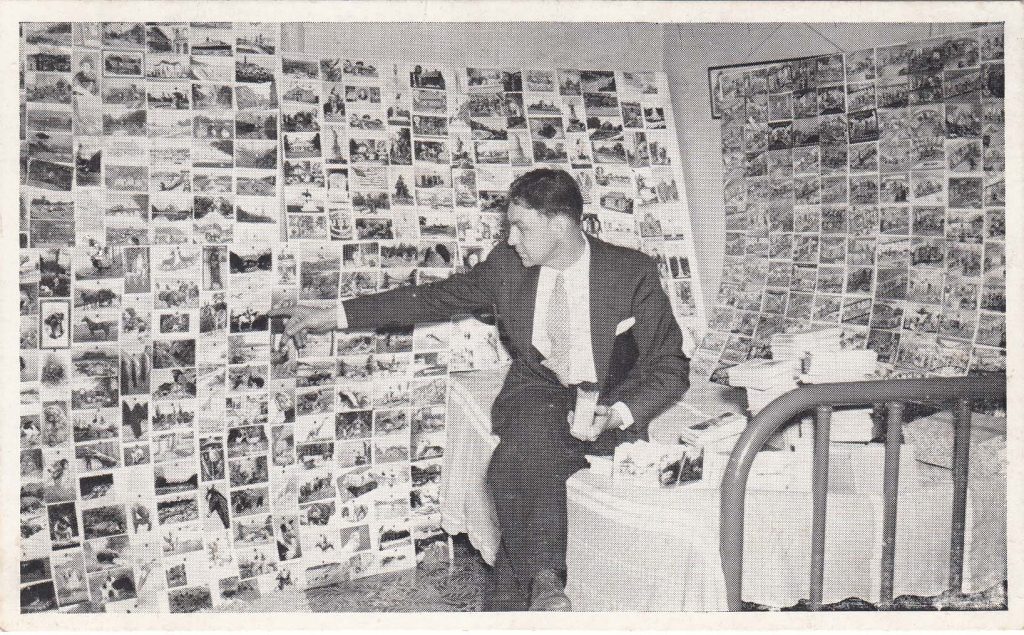

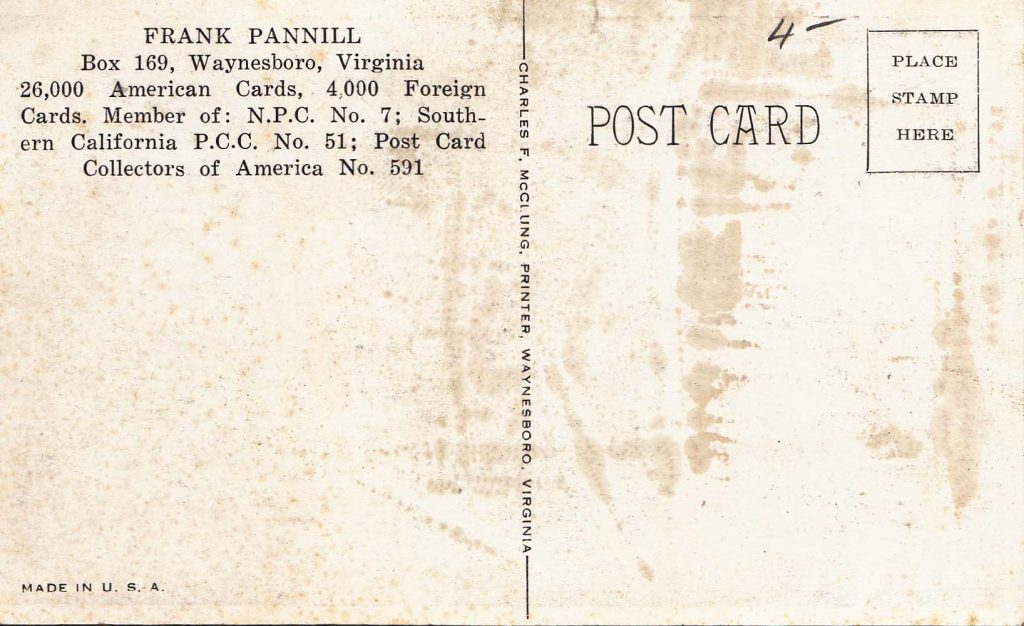

One of the Largest Collections in the World

My title comes from a headline that recently caught my eye. It appeared in The Post Card World, a postcard collectors’ magazine that began publishing in St. Louis in 1906. How many cards, I wondered, were in “one” of the “largest collections in the world”? The opening sentence provided the answer: “Beginners in the post card collecting fad will, no doubt, be greatly surprised to learn that there is a collector in Paterson, N.J., whose collection numbers 10,000 cards, but it is fact.” Even today, the number is impressive and this, after all, was in 1906, a point only a few years into the collecting obsession.

It’s trivial facts about postcards and postcard collectors like these that obsess me. Like most longtime collectors, I’m often–no, always–irrational about postcards. It’s not just the cards themselves, I’m also obsessed with the early days of collecting. What was it like to be alive and collecting during the golden age of postcards? That title, coupled with many years of researching and collecting, prompts these thoughts.

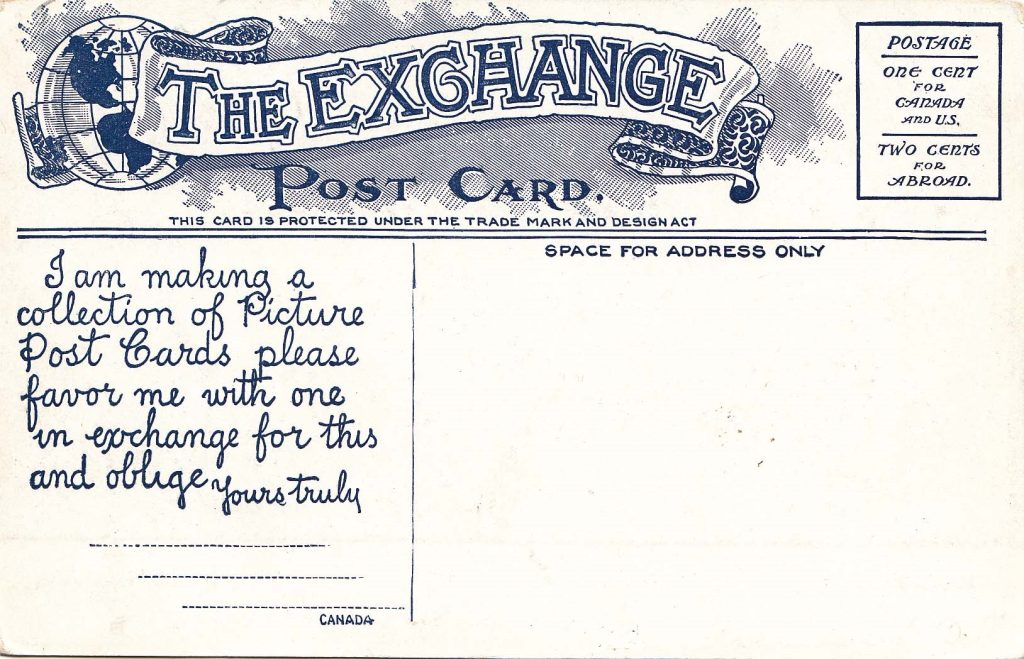

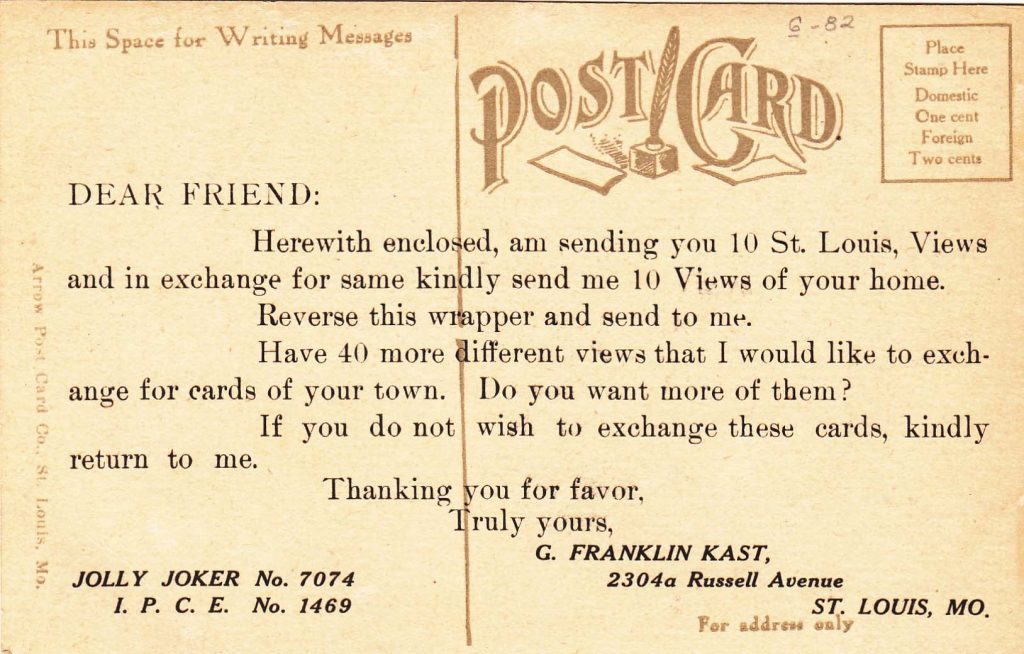

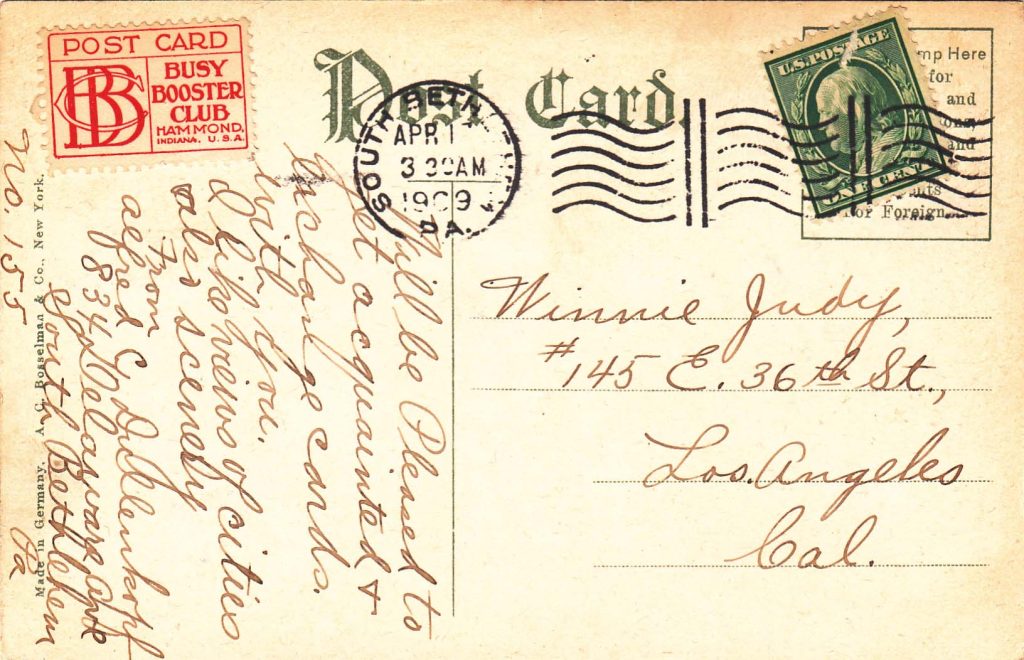

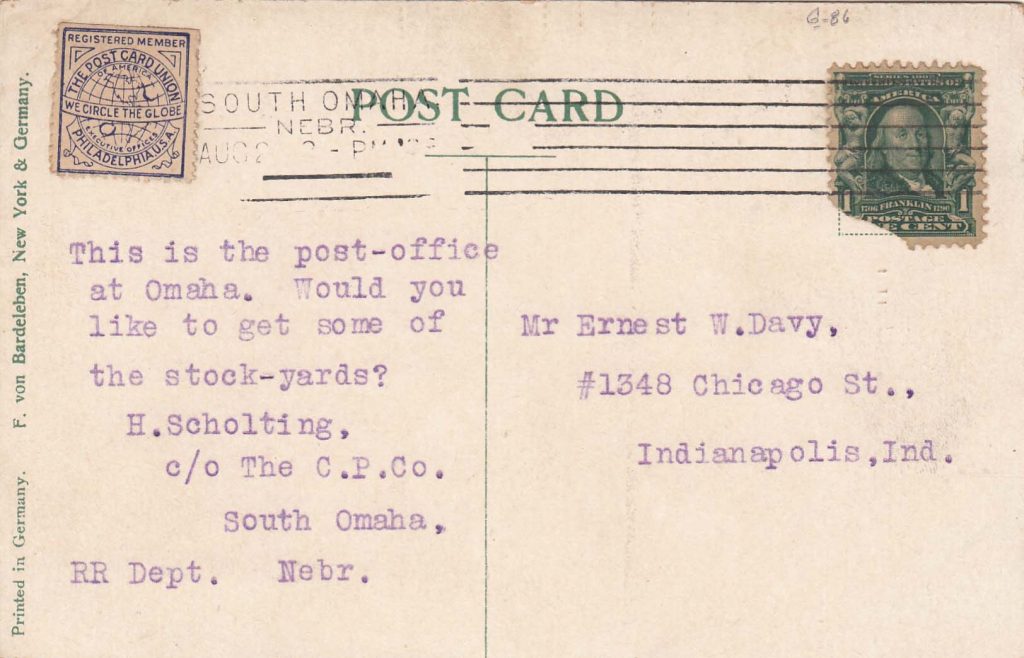

Much of Collecting Was Exchanging

The collection of cards mentioned was owned by Mrs. George Baum of Paterson, New Jersey. She began collecting in 1901 and in 1906 was adding cards to her collection at the rate of a hundred per week. In her record week, she “received” 158 in one day. The verb “received” is crucial. Mrs. Baum, like most early collectors, acquired her cards through the mail from other collectors. They were “postcard exchanges,” often done a card at a time. There she was living at a time when you could visit a local postcard store and purchase hundreds of cards for a few cents each and she, like many others, relied instead on exchanges with other collectors throughout the world.

Mrs. Baum’s method of collecting cards is echoed in dozens of stories that I have read about early collectors. L. C. Wheeler writing in the same issue of The Post Card World, noted: “I began collecting in the year 1902, at which time we had no such societies [postcard collecting clubs] as we have at present, where we could get such reliable names [of people willing to exchange].” “Look at the fine cards we receive from our foreign cousins, together with a good variety of postage stamps, post marks, and autographs,” he continued. “I make a specialty now of collecting only from foreign countries and small islands and try to get six cards from each place, of which I have succeeded in getting them from 103 different places.”

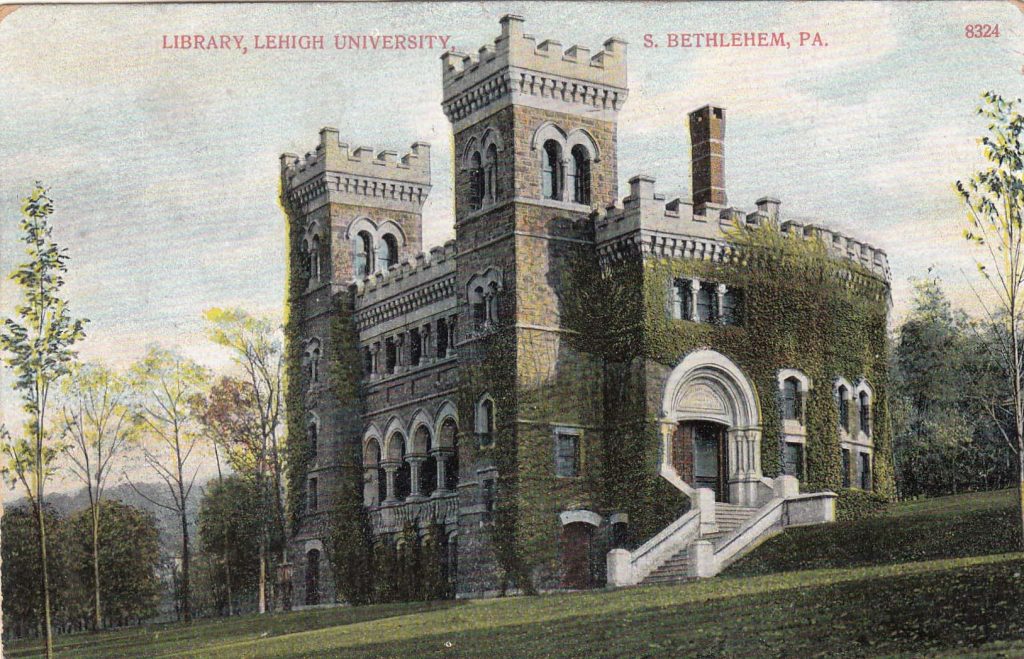

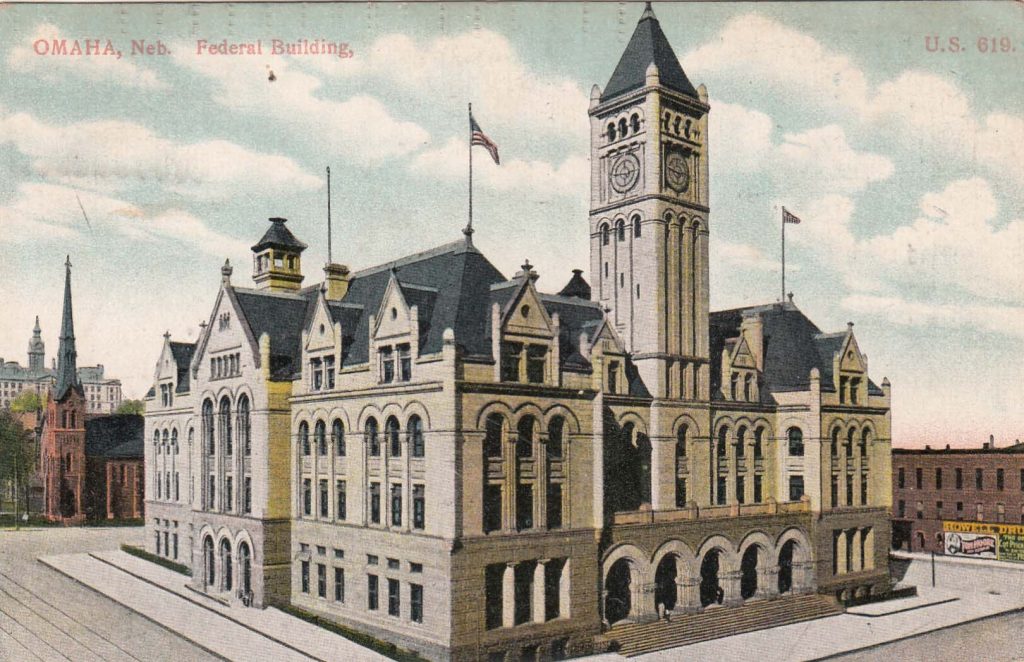

Early Collectors Were “into” Views

If you exchanged postcards, you often sent local views. Now to me that seems a little surprising. To my mind, local views are of local interest. Why should I want to see a view of the courthouse or a local church in a neighboring community hours or days away? But that’s exactly what many exchanges involved. Mr. Wheeler wrote, “Every city in the world and most of the smaller towns have a set of cards bearing views of the principal places of interest, the public and prominent buildings, large fires, and pretty local scenes.” On postally used early views of public buildings, it is not surprising to see a message that says something like, “Here’s a view of new courthouse.”

Why? The world was smaller because travel was difficult. The major roads were unpaved. Getting to town was a major triumph; getting from one town to another was a rare occasion. Travel abroad, especially to exotic places, was out of the question except for the very wealthy. Newspapers and magazines carried no photographs. People were curious about the world outside of their immediate environment. Today, we’re jaded. We fly from coast to coast, from country to country, without thinking about it; we drive for hours. We expect to see on television the latest disaster as it happens.

In the same issue of The Post Card World was an advertisement from a publisher of postcards in Tipton, Staffordshire, England. Did he advertise Louis Wain postcards? Golliwogs? Tuck novelties? Signed art nouveau? Mechanicals? No. Half of his advertisement was devoted to the type of view that no one wants today: “Gems of English Scenery;” “Castles of England,” “English Cathedrals,” and “English Lakes.”

Early Collectors Saved Greeting Cards Sent to Them

Early collectors didn’t just collect views. In an era before the folded greeting card that today is so common, people sent holiday or birthday greetings postcards. Early collections tend to have many greeting postcards that were mailed to the collector or to members of the collector’s family. Just to judge from what I’ve seen, very early collectors didn’t tend to have albums of greeting cards which they purchased at a postcard shop with the intention of mounting them in albums.

No One Collected Postcards Advertising Products or Services

In the years I have collected and researched, I’ve never found evidence that suggested that early collectors thought that advertising postcards were an appropriate part of a postcard collection. I’ve never seen an early collection (amassed prior to 1915) that contained advertising postcards other than a few sent to family members. Why? I guess for the same reason that most collectors today do not save the postcard advertisements that arrive in the mail. They are an intrusion – sent to us from someone we do not know to encourage us to buy something we do not want. Are you in doubt? Watch your mail. How many postcards do you receive each week? How many do you add to your collection?

Collecting by Sets Was Fairly Uncommon

Early collectors occasionally acquired “sets” of cards, but in general they seemed more interested in examples rather than completeness. Mrs. Baum, the article tells us, had among her collection, “complete series of the Paris, Pan-American, and St. Louis World Fairs, nearly every prominent building in the United States, every crowned head and ruler of the countries of the globe.” Presumably Mrs. Baum had the sets of the “official” cards for the expositions listed. She also has “some beautiful specimens of the illustrators’ work.” I’ve never seen any references to the very early collectors as “working on sets.” Probably, this was so for a couple of reasons.

With the exception of a publisher like Raphael Tuck, most postcard publishers did not really market cards as “sets,” even though they were often published in sets. While there are examples of large sets that came in boxes or envelopes, most postcards were simply put out in the stores on racks or in piles. Often cards were sold to postcard dealers in large quantities – an assortment of greetings for example. If a postcard dealer sold out of a single design in a set, it was impossible to re-order that single design.

If Early Collectors Ignored All This Stuff, why Does It Still Survive?

I think that the majority of postcards that survive today did not descend through the hands of early collectors or even through the family’s postcard album. Instead, they came from store stocks or publishers’ stocks that were liquidated years later. Consider how many postcards that are found in mint condition. In some cases, it is more difficult to find a postally used example than it is to find an unused card.

Twenty or thirty years ago it was not uncommon to find shoeboxes of mint cards. These were often highly desirable cards like Nash Labor Day cards, Coney Island hold-to-lights, Albertype sets, and Tuck or PFB greetings. When the golden age of the postcard was over, surely millions of cards still survived in the hands of stores, printers, and distributors. That’s where the majority of our postcards come from.

In a way knowing this destroys the fantasy. I used to imagine what it was like to collect postcards during the height of the craze, when the stores were full of mint condition cards and available for a few cents each.

Postcard collecting was first called philocarty. An early organization in the 1910 era was the Jolly Jokers. With a distinguishable imprint, magazine publication had distribution of over 5,000.

In 1911 the Dry Goods Reporter found 45-50 letters were needed to produce one pound and generated a profit 90 cents to a dollar. Postcard count soared to 160 for the same weight and profit was $1.60. During this Golden Age of communication it was estimated 770,500,000 cards were annually processed by the post office. Staggering numbers.

What Americans did 123 years ago became habitual to the point of comfort.