Defining the Demonic

Although Jacques Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire infernal, a monumental compendium of all things diabolical, was first published in 1818 to much success, it is the fabulously illustrated final edition of 1863 which secured the book as a landmark in the study and representation of demons. Ed Simon explores the work and how at its heart lies an unlikely but pertinent synthesis of the Enlightenment and the occult.

PUBLISHED

October 25, 2017

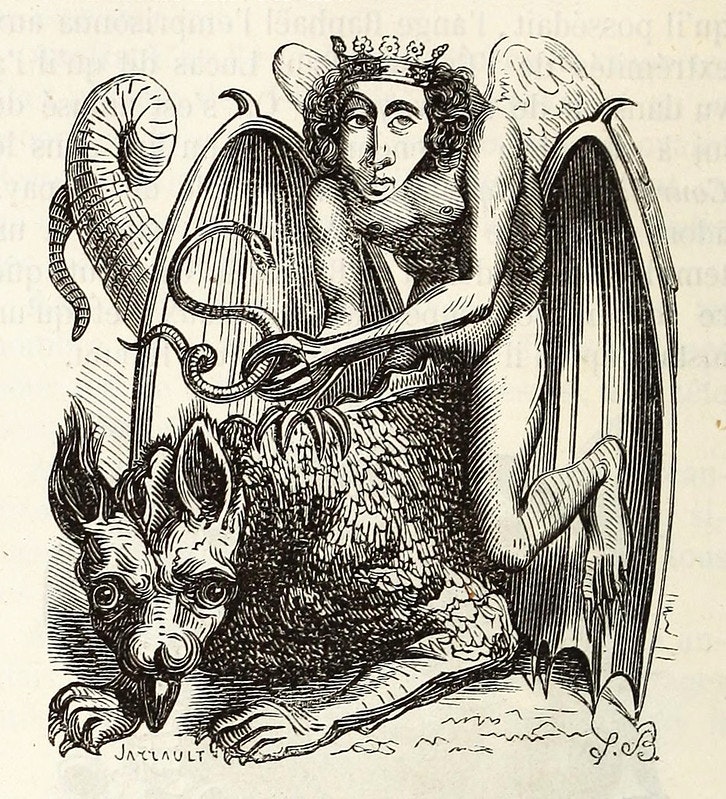

Astaroth, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

There, between the entry for a seventeenth-century Anglican theologian named Assheton and one for the Levantine goddess Astarte, is the demon Astaroth. As depicted by the French artist Louis le Breton for his fellow countryman Jacques-Albin-Simon Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire infernal, Astaroth is a skinny man with reptilian claws punctuating long hands and feet, hobbled over on the back of a lupine demon sporting a massive pair of bat wings and a serpentine tail. His face — described by Collin de Plancy as that of a “very ugly angel” — is rendered by le Breton as thin and effete, almost equine, with eyes dismissive and uncaring, a slight sneer of cold command. Ignoring Astaroth’s claws and demon mount, his look of calculated intelligence could easily be that of one of the armchair intellectuals who dined with the philosophes of the Enlightenment Paris of Collin de Plancy’s youth.

Not an entirely inappropriate connection, for the Dominican inquisitor Sebastian Michaelis, who classified the demons he encountered as an exorcist at the infamous monastery of Loudun in the seventeenth century, associated Astaroth with the new rationalist philosophies that were just being born in France. Michaelis’ Astaroth was a kind of hellish René Descartes, who drew the nuns and priests of Loudun astray with the pernicious promises of Epicureanism and invitations to “Do what thou wilt”. Perhaps for Collin de Plancy, born almost two centuries later amidst the convulsions of revolution, the thin, reptilian demon with the aristocratic bearing still represented some of the dangers of the new learning, for Astaroth “willingly answers the questions he is asked about the most secret things, and . . . it is easy to have him talk about creation”.

Astaroth is a convenient symbol for the oddity of Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire, for the demon represents a muddle of cultural forces: rationalism and superstition, systematization and the occult, the Enlightenment and the Romantic movement. When the Dictionnaire was first published in 1818, Collin de Plancy was a dutiful student of the new rationalism who set out to catalogue what he called “aberrations and germs or causes of errors”. As he labored at subsequent editions, however, the secular folklorist found himself more and more pulled in by the lure of demonology, a passion which would eventually lead him, by the 1830s, to enthusiastically embrace Catholicism. By the Dictionnaire’s final edition of 1863, the publishers could assure the reader that the “errors” previously highlighted had now been eliminated, the catalogue now fully congruent with Catholic theology. The preface authoritatively claimed that Collin de Plancy had “reconfigured his labors, recognizing that superstitious, foolish beliefs, occult sects and practices . . . have come only from deserters of the faith.”

All together, across nearly six hundred pages, Collin de Plancy provided entries for sixty-five different demons, including favorites from the pages of Dante, Milton, and others, such as Asmodeus, Azazel, Bael, Behemoth, Belphégor, Belzebuth, Mammon, and Moloch. The most interesting edition of the text is the final one of 1863, illustrated with creepy exactitude by le Breton, whose brilliant Doré-esque engravings elevate the work beyond the relative staidness of previous editions.

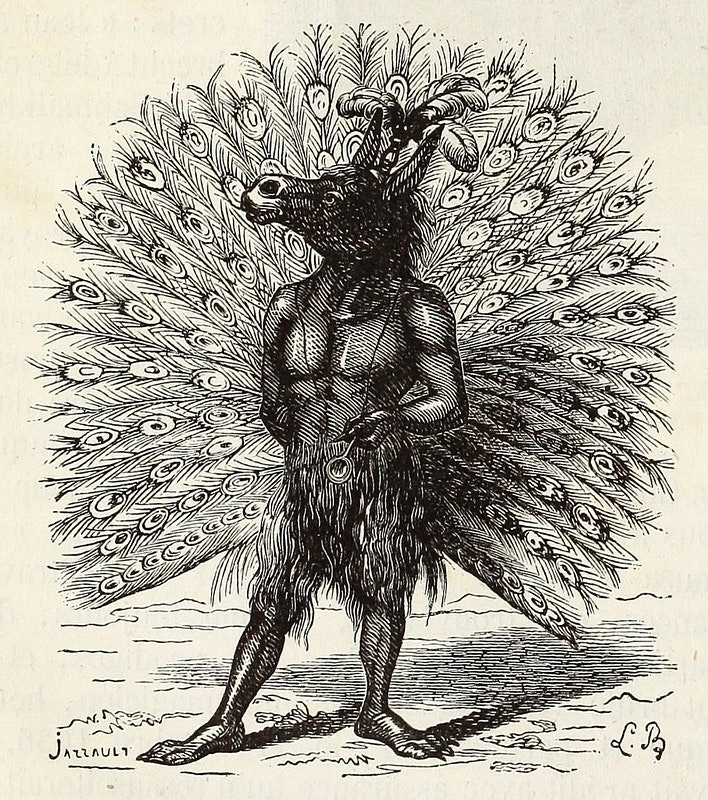

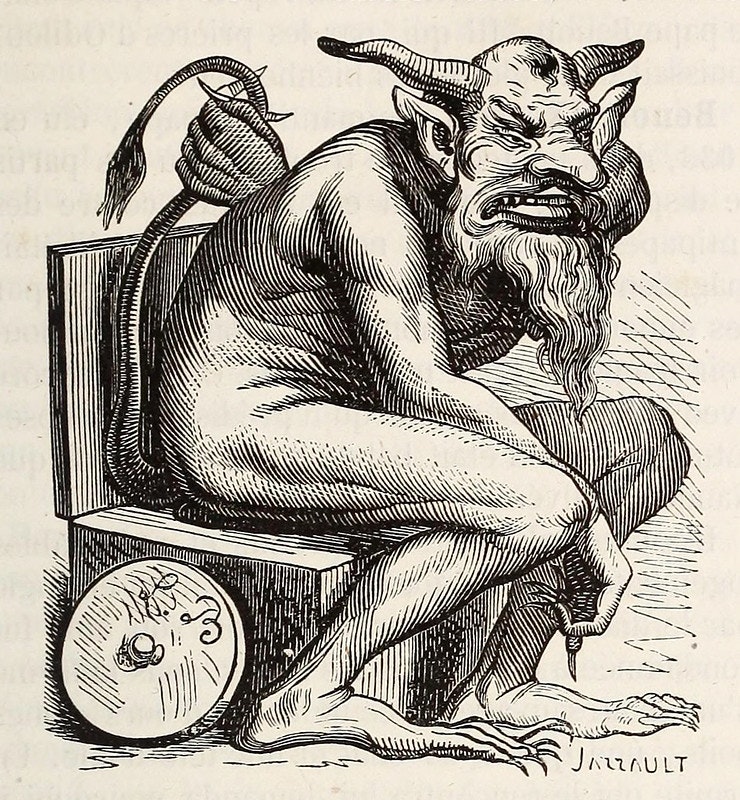

Adramelech, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

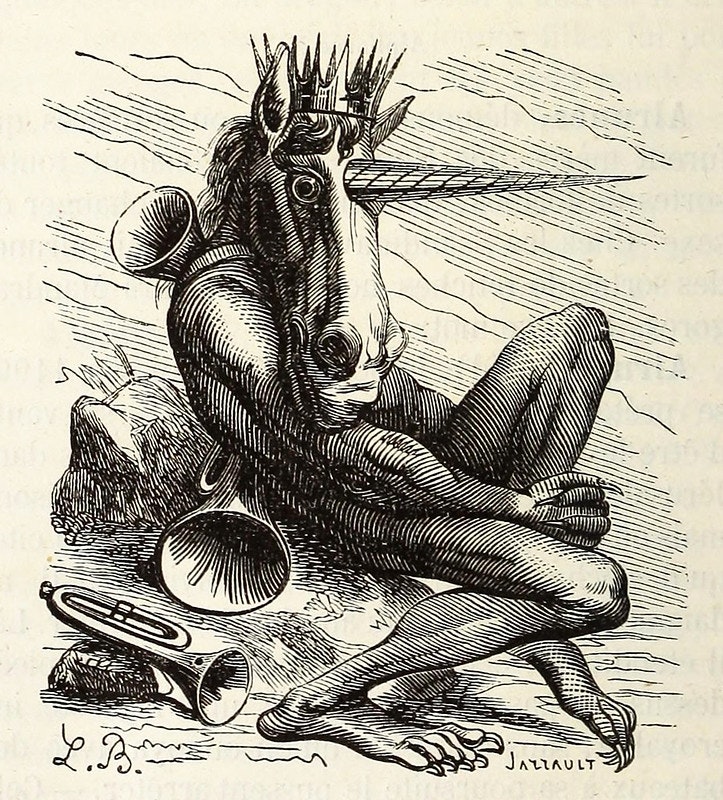

It’s both edifying and frightening to consider the magnificence of some of these illustrations. For example, among the more minor demons there is “Adramelech, great chancellor of the underworld, steward of the wardrobe of the sovereign of the demons, president of the high council of the devils”, who “showed himself in the form of a mule, and sometimes even that of a peacock”. Le Breton’s illustration portrays him in full pompous glory as an ass-headed version of the Yazidi’s “Peacock Angel”. Or there is Amduscias, in “the form of a unicorn”, to whose voice “the trees bow”, and who “commands twenty-nine legions.”

Amduscias, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

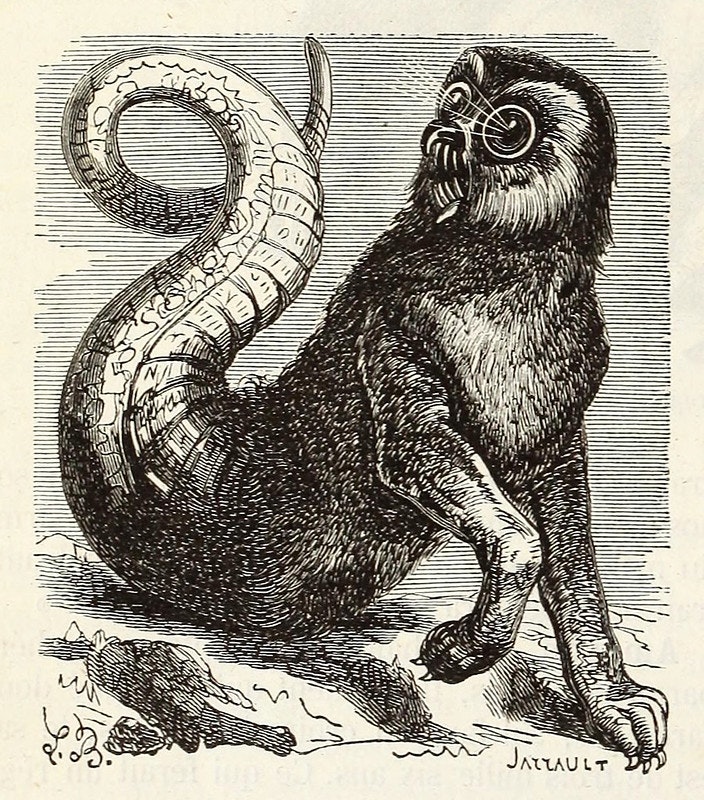

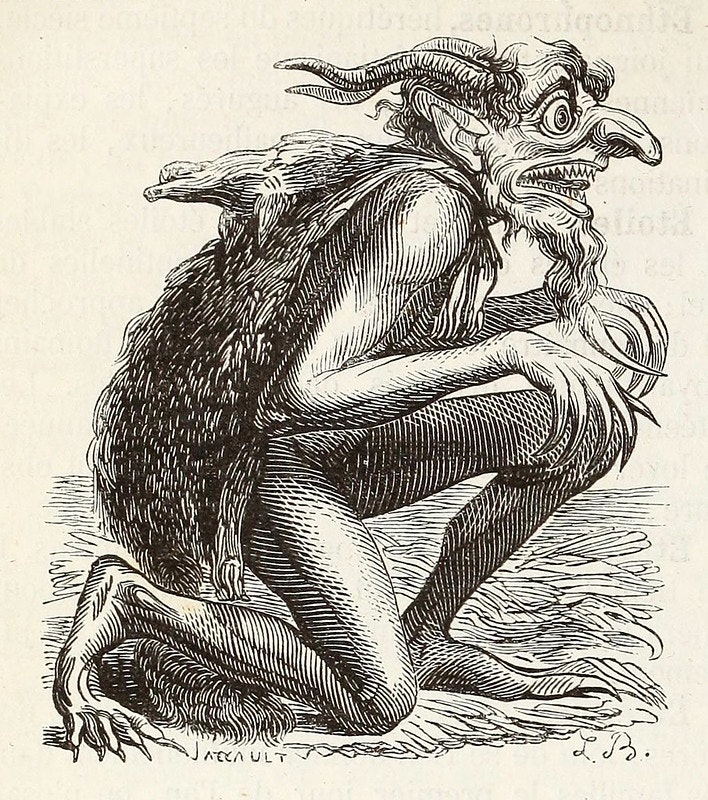

A few pages later there is Amon, a horrific hell beast with globular pitch-black eyes, a “great and powerful marquis of the infernal empire” who appears as a “wolf, with a serpent’s tail . . . [whose] head resembles that of an owl, and its beak shows very sharp canine teeth.” As if le Breton’s rendition of the beast wasn’t terrifying enough, Collin de Plancy reminds us that this nightmare creature “knows the past and the future”.

Amon, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

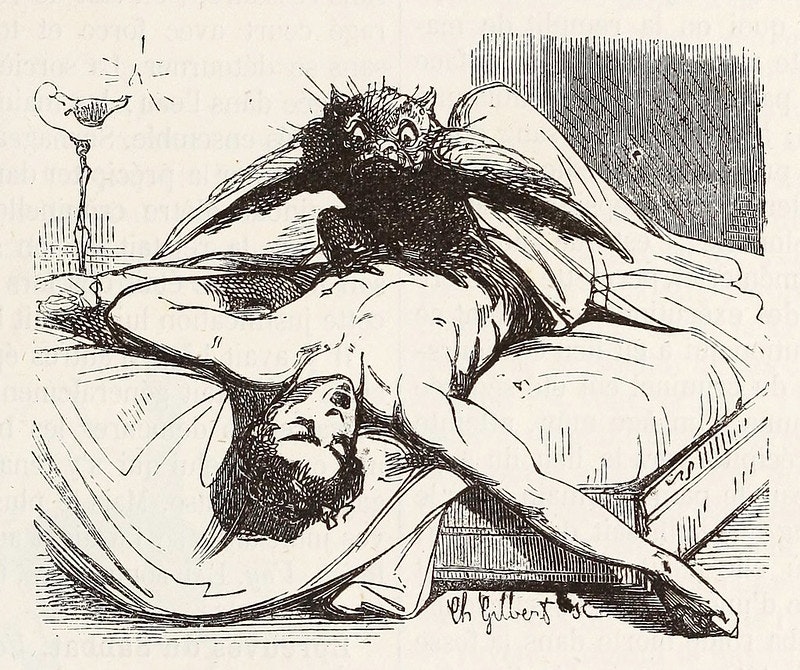

And then there is Ephialtes — a pug-faced, bird-winged, wild-eyed little gremlin perched atop the chest of a man, like Fuseli’s Nightmare — who Collin de Plancy describes in just a single sentence, explaining that he derives from the “Greek name for the nightmare . . . a kind of incubus that stifles sleep.”

Ephialtes, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

Eurynome, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

Belphégor, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

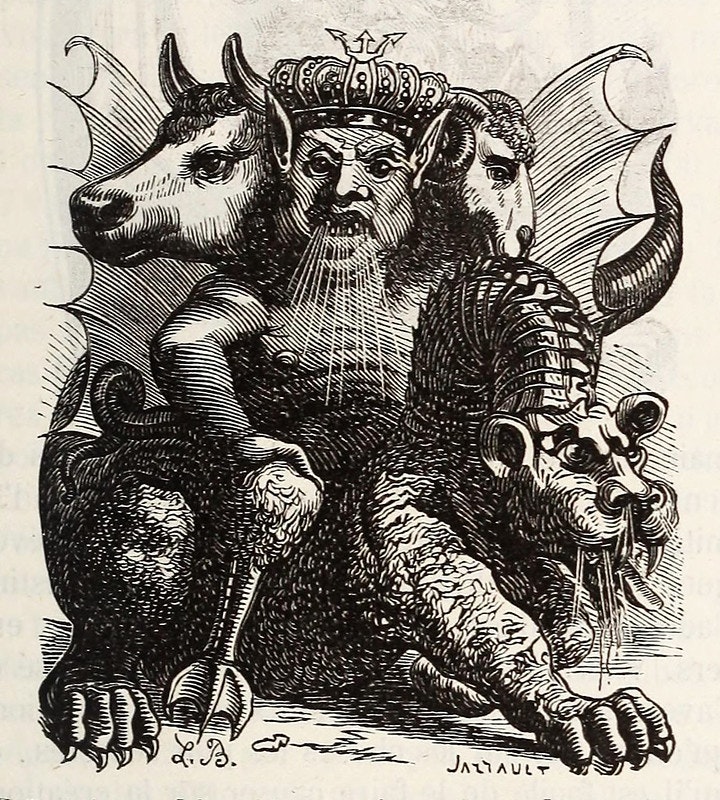

Of course, Collin de Plancy’s concern in the Dictionnaire infernal wasn’t just the defecation of minor demons. He also aimed to provide instruction on both the history and the practical utility of the more exalted among Satan’s minions. There is Asmodeus, who the Talmud claimed was born of a succubus who slept with King David, but who Collin de Plancy argued was “the ancient serpent who seduced Eve.” Associated with lust, Asmodeus is presented as a fearsome three-headed monstrosity, though not one above doing the bidding of King Solomon (regarded by the occult tradition as having had a special ability to control demons), who “loaded him with irons and forced him to help build the temple of Jerusalem.”

Asmodeus, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

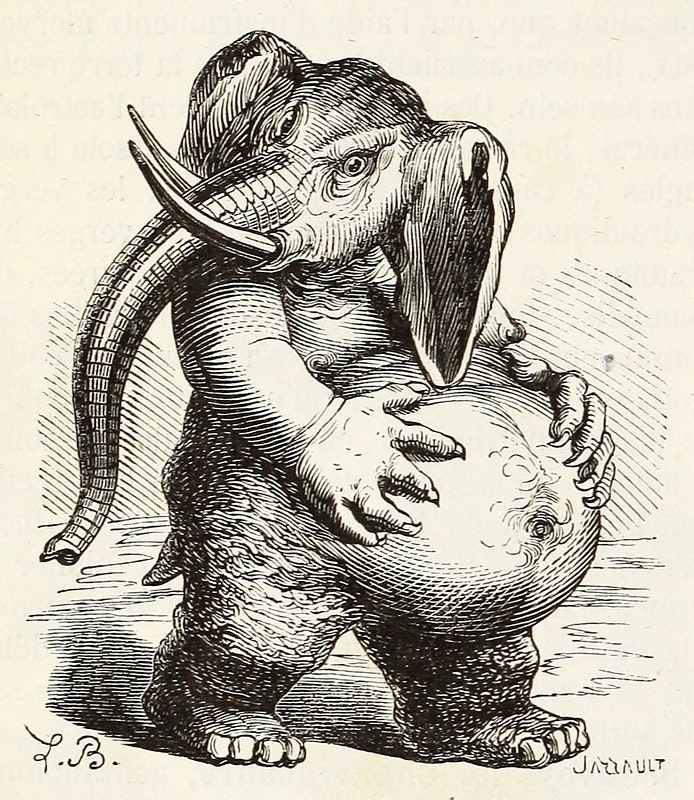

Or reflect upon that “heavy and stupid demon” Behemoth. Calling to mind his appearance in the Book of Job, Collin de Plancy wrote that some “commentators pretend that it is the whale, and others that it is the elephant”. Le Breton chose to depict Behemoth as a bipedal version of the latter, clutching his hairy, engorged belly like some sort of malevolent Ganesh.

Behemoth, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

Bael, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

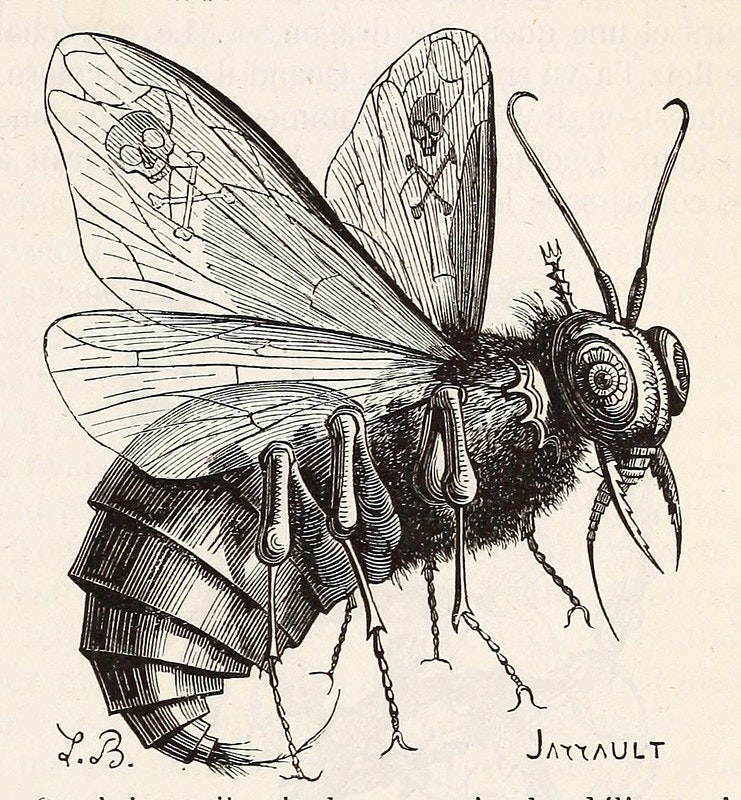

The Phoenician god Ba’al, from whom Collin de Plancy’s Bael derives his name, was associated with all manner of idolatries and blasphemies, and is also the inspiration for that other lieutenant of hell, Belzebuth (or Beelzebub), the trusted advisor of Lucifer whose name appears in the records of exorcists from Loudun to Salem. As Belzebuth literally means “Lord of the Flies”, le Breton decided to depict this demon as a startlingly biologically accurate insect, with long pinching mandibles, weirdly human eyes, and a skull and crossbones upon his paper-thin wings. If anything, the strange verisimilitude of the insect-like creature makes le Breton’s image all the more terrifying. His segmented thorax and spindly arms recall the flea magnified by Robert Hooke two centuries earlier, the English polymath's Enlightenment monstrosity demonstrating that the nightmares of reason and superstition are not always as divergent as we might think.

Belzebuth, from the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

This connection between the ideals of the Enlightenment and the old world of magic and superstition from which these demons sprung was, in many ways, made literal by the figure of Collin de Plancy himself. He was born in 1793, only four years after the crowning (or most condemnatory) event of the Enlightenment: the French Revolution. Perhaps in reaction to that affair, he added the aristocratic “de Plancy” to his otherwise plebeian name. Indeed it was not just a plebeian name, but one with positively republican associations, for Collin de Plancy’s maternal uncle was none other than George Danton, the radical president of the Committee on Public Safety who, like so many of his fellow Jacobins, ultimately found his severed head looking up at the guillotine blade one morning in the month of Germaine.

Like his uncle, Collin de Plancy was originally a partisan of liberty, equality, and fraternity, an enthused reader of Voltaire and a zealous rationalist and skeptic; also like his uncle, he would ultimately see himself reconciled to that Church he had rejected, though with a detour through the darker corners of demonology. As with the many demonic chimeras that populate his dictionary, Collin de Plancy was a mélange of disparate parts. He combined the rectilinear logic of men like Voltaire and Diderot with the chthonic visions of the symbolist and decadent poets of a generation later — Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and Verlaine, who drunkenly stomped through the rainy streets of Paris clutching their fleurs du mal. Collin de Plancy did not just convince himself that demons were real, but indeed he developed a wish to control them through language, a desire as fervent as that of his Enlightenment forebears to categorize and define words and ideas in dictionaries and encyclopedias. The demonologist was a man stuck between logic and faith, the salon and the Hellfire club, who heard the screams of horrific monsters while writing with the sober pen of a naturalist.

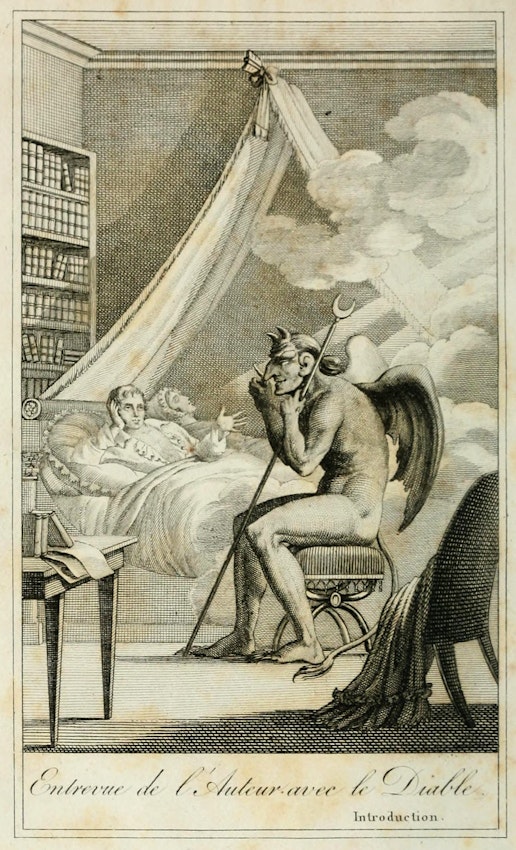

Frontispiece to the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy Le diable peint par lui-même: ou, Galerie de petits romans, de contes bizarres, d'anecdotes prodigieuses, in which the "author" (Collin De Plancy) is shown chatting to the devil in the night — Source.

Like its creator, the Dictionnaire spanned the interests of two eras. It recalls such grimoires (practical manuals of magic) as Johann Weyer’s sixteenth-century Pseudomonarchia Daemonum, or the seventeenth-century Lesser Key of Solomon, as much as it does the Enlightenment’s systematized compendiums of knowledge, such as Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie. There is ambiguity in the book’s project itself, for what could be more modern than the dictionary, and yet what could be more antique than the knowledge collected in this particular dictionary?

Despite ancient and medieval precedents across several different cultures (one can think of Aristophanes of Byzantium, who compiled a type of dictionary called the Lexeis two centuries before Christ), the dictionary and especially the encyclopedia were products of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. For Dr Johnson and his Dictionary of the English Language, or James Murray, who, in the Bodleian’s scriptorium, assembled the testament to humanity that is the Oxford English Dictionary, positivist knowledge could be found in the process of collection and measurement. The dictionary was sober, rational, and practical. Etymology was like dissection, another Enlightenment innovation, and the dictionary a sort of dissection theater. For Johnson, the dictionary was a reaction to “speech copious without order, and energetick without rules”, it served to tame vocabulary, for its approach to language was one “reduced to method”.

But what then of Collin de Plancy’s infernal version? Is it a dictionary by name only, or could the affinities touch a deeper vein? In his Grimoires: A History of Magic Books, the historian Owen Davies writes of how grimoires are marked by a “desire for knowledge and the enduring impulse to restrict and control it”, a description that could certainly be applied to the projects of Johnson and Murray. “Grimoires exist”, he goes on, “because of the desire to create a physical record of magical knowledge, reflecting concerns regarding the uncontrollable and corruptible nature of . . . sacred information.” While it’s true that the grand experiment of the Enlightenment was supposedly to shine the light of rationality upon the shadows of superstition, the desire to assemble all possible information is one which the grimoire and the dictionary share. And this yearning towards completion and the all-encompassing is not just a superficial similarity, for in their obsessions with words and language, the grimoire and the dictionary share a common faith — that mere verbal pronouncements have the ability to rewrite reality itself. Both kinds of book are partisans of a Platonist philosophy that sees a type of word magic as being able to enact transformations in real life. For the rationalist lexicographer this means that mastery of rhetoric and syntax can affect our lives through the ability to explicate and convince; for the wizard this means that the magic of words can conjure alteration. In both cases, words have the power, if they’re properly organized, to change the world for better or for worse.

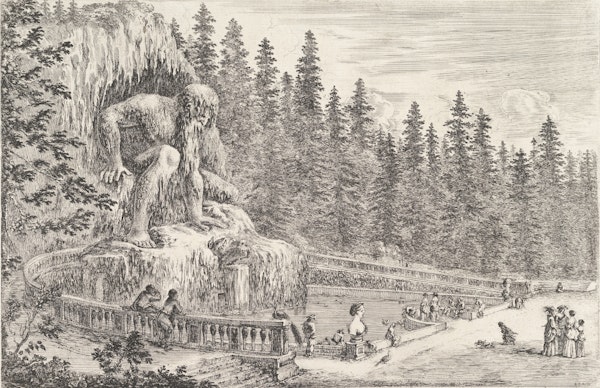

Detail from the frontispiece to the 1863 edition of Collin de Plancy's Dictionnaire infernal — Source.

At the heart of this shared mission is the fact that both magic and reason have a motivating belief in the inherent explicability of reality: that there is a given order to the world and that human minds can comprehend and control this order. Whether that order is supernatural or natural is somewhat incidental; that there is structure to the system is what is important. Collin de Plancy’s dictionary may be a grimoire, or his grimoire may be a dictionary, but fundamentally the distinction between them is less stark than might be supposed.

Ilan Stavans writes that “dictionaries are like mirrors: they are a reflection of the people who produced and consumed them.” If this is true, then the Dictionnaire infernal is not just a reflection of Collin de Plancy, a man who dwelled among shadows yet desired to illuminate, but also a reflection of our own modern world. With their words listed like demons, their concern with proper order and grammar (lest our spells don’t work), dictionaries can be seen as modern, secular grimoires. The Dictionnaire infernal, far from being an archaic remnant, reminds us that sharp distinctions between antiquity and modernity ultimately mean little. Ours has always been, and always shall be, a demon-haunted world. But, with apologies to C. S. Lewis, what grimoires prove is not that demons exist, but that they can be tamed. If there is any consolation to be found, it’s that controlling our demons is possible if we’re able to name them, whether they are of the supernatural or of the rationalist variety — and in either case, a dictionary is what we shall need.

Ed Simon is a staff writer for The Millions, which the New York Times has called the “indispensable literary site”. A specialist in early modern and early American literature, he holds a PhD in English from Lehigh University, and his most recent book is Printed in Utopia: The Renaissance's Radicalism (Zero Books, 2020).

No comments:

Post a Comment