Art World

‘We Shouldn’t Own These Things’: 5 Takeaways From a Landmark Conference on Collecting Land Art

The event at the Frick Collection in New York was full of revelations.

In the 1970s, Land artists like Michael Heizer, Nancy Holt, and Robert Smithson had a vision: not only to create artworks at monumental public scales, but also to break free from the gallery-collector business model and what they deemed to be an overactive art market. They wanted to make artworks no one person could truly own.

And yet, throughout the history of Land art, there were financiers and supporters who funded their expensive and elaborate projects, including dealers like Virginia Dwan and collectors like Robert Scull.

So how, exactly, did those relationships work? That was the topic of discussion at a one-day symposium organized by the Center for the History of Collecting at the Frick Collection in New York last week.

Participants at the conference, titled “Collecting the ‘Uncollectible’: Earth and Site-Specific Sculpture,” included Dia Art Foundation director Jessica Morgan, artist Michelle Stuart, National Gallery of Art curator James Meyer, mega-collector and ex-Dia chairman Leonard Riggio, and his fellow collector and ex-NPR CEO Jarl Mohn, who offered the event’s choicest quote: “We shouldn’t own these things.”

Here are 5 takeaways from the event.

Jessica Morgan, director of the Dia Art Foundation, in conversation with collectors Jarl Mohn and Leonard Riggio at the Center for the History of Collecting’s Land art symposium. Photo: George Koelle.

What Is Now Coveted Was Once Unwanted

In his lively presentation, James Meyer (who curated the National Gallery of Art exhibition “Los Angeles to New York: Dwan Gallery, 1959–1971“) framed dealer and patron Virginia Dwan as a devoted supporter of avant-garde art—up to a point.

The 3M heiress had the first bi-coastal gallery (in Los Angeles from 1959–67 and in New York from 1965–71), and showed tons of now-blue-chip artists: Franz Kline, Philip Guston, Yves Klein, Robert Rauschenberg, and Roy Lichtenstein, among others.

But nothing sold, as Meyer pointed out, and the wealthy Dwan’s business became so unsustainable that she was forced to close the gallery in 1971.

Robert Smithson, Spiral Jetty (1970). Courtesy James Cohan Gallery.

Land Art Penetrated the Cultural Consciousness Even When It Was New

New Yorker cartoonist Warren Miller was hip to Land art and its patrons when it was still an avant-garde form, art historian Suzaan Boettger pointed out in her talk.

In 1972, Miller published a cartoon of a businessman in a suit, seated in a booth with a wary-looking woman, delivering a punch line that updated a familiar trope: “How’s about you and me flying out to Utah and taking a gander at some of the earthworks I’ve financed?”

In another cartoon, from 1979, Miller acknowledges the fraught state of collecting Land art, as an irate office worker points to a heap of soil piled up against a colleague’s wall and says, “You call this a mere bagatelle?”

Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels (1973–76) in the Great Basin Desert in Northwestern Utah. © Estate of Nancy Holt/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Courtesy the Estate of Nancy Holt.

By Nature, Land Art Is Vulnerable

Art vandalism goes back centuries—just visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Temple of Dendur to see some ancient names scrawled by heedless visitors. But Land art, away from the watchful eyes of museum guards, is especially open to abuse, conservator Rosa Lowinger stressed.

Roy Lichtenstein’s public sculpture Mermaid, on the lawn of the Fillmore at the Jackie Gleason Theater in Miami, includes a pool of water in which homeless people are known to bathe. Meanwhile, Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s Dropped Bowl With Scattered Slices and Peels (also in Miami) is sometimes used as a skateboarding ramp.

And while you can fix some things, there are others you just have to live with.

People fire guns into Nancy Holt’s masterwork Sun Tunnels in the Utah desert, Lowinger said, pointing out that the traces cannot be removed because they are literally molten metal.

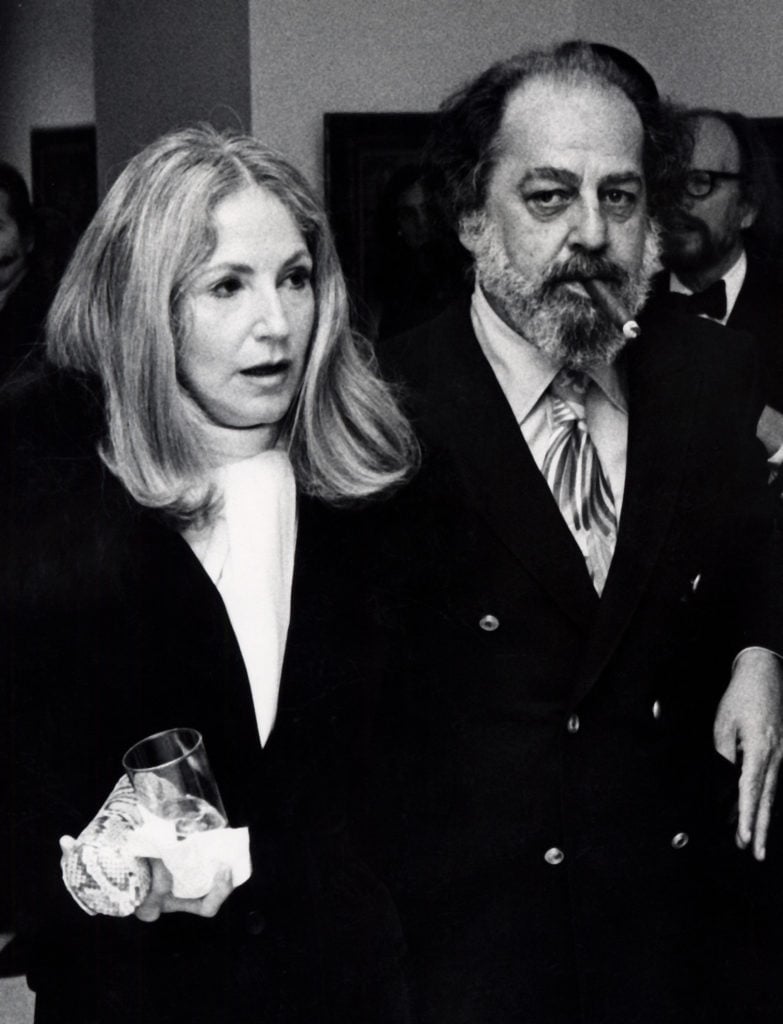

Ethel Scull and Robert Scull. Photo by Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection/Getty Images.

Men Often Got Patronage From Collectors, but Women Had to Scramble for Grants

Then, even more so than now, women fought an uphill battle to get support to create anything near the scale of Smithson’s or Heizer’s projects, said Kelly Kivland, an associate curator at Dia.

Michelle Stuart noted that even when she got Guggenheim, NEA, and state arts grants to support her work, the amounts were often measly. In the 1970s, she received just $2,000 from the Portland Center for the Visual Arts to create Stone Alignments/Solstice Cairns (1979) in East Columbia Gorge, Oregon.

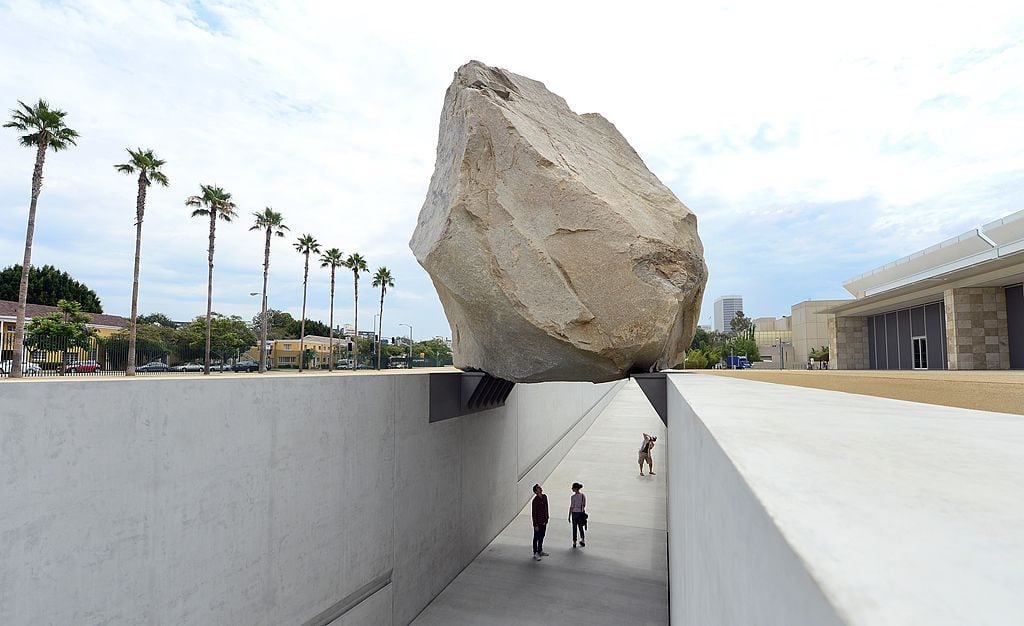

But when Michael Govan, director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, needed support for Michael Heizer’s mammoth Levitated Mass, he went back to Jarl Mohn so many times, Mohn said, that when he finally wrote a check, it was on the condition that Govan not call him again for two years.

And sometimes, such requests created friction between collectors and artists.

Dia curator Alexis Lowry noted that collector Robert Scull underwrote projects by Heizer with the promise that the artist would give him a leather-bound book about his massive Nine Nevada Depressions. Scull gave the artist $17,000, but in the end, the artist found the book project so contrary to the spirit of his work that he took it back and destroyed it.

James Turrell’s Roden Crater (ongoing). © 2017 Skystone Foundation. © James Turrell.

Jarl Mohn Has One Final Project on His Mind

Asked whether he had a dream project that he would support if money were no object, Mohn said he would install Marcia Hafif’s 1973 work An Extended Gray Scale (which consists of 106 22-inch-wide paintings) in a single row, not in a grid, as it has often been displayed.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

No comments:

Post a Comment