We Koreans, my father once argued, have thicker legs than our Asian neighbors, a trait that comes with athletic benefits and drawbacks. Big legs are good for short bursts, but the added muscle weight leads to stamina issues. This was in 1992, and my father, a chemist who tended to see things in terms of inputs and outputs, was explaining why our home country, South Korea, which had never meaningfully competed in the Winter Olympics, had won a handful of medals in short-track speedskating. (A decade later, he would revise this theory for our run to the semifinals of the World Cup in soccer. We had finally found a manager, he said, who understood genetics.)

In the 26 years since then, Koreans have come to dominate other things, many of them unrelated to innate leg strength. We rule the world in women’s golf, e-sports, break dancing, drinking (by volume of shots per week) and archery. The specificity of these pursuits has led to wild speculation among the diaspora about why we’re so good at such random sports.

We might not actually want to know the answer. The most sensible and palatable explanation, of course, is economic. “In the ’80s and ’90s, the national athletic association was looking for Olympic sports that Koreans could do well in,” the anonymous writer behind the influential blog “Ask a Korean!” told me. “They decided to focus on short track because it was a relatively new event.” Skating programs opened up at every rink; high schools and universities started sponsoring teams. A national infrastructure was built. Korea, in effect, cornered a new medals market.

But a more compelling, if troubling, reason for Korean short-track domination might be glimpsed, oddly enough, in “Planet B-Boy,” a 2008 documentary about international break-dancing culture. In one memorable scene, the Gamblerz, at the time the Yankees of break dancing, are rehearsing in their studio in Seoul. As the dancers contort and invert their bodies, you see that break dancing, which must look stylishly effortless, is actually created by brute strength and technical repetition. A Gambler named Still explains why his teammate Laser became the best head spinner in the world. “Laser has spent the past five or six years spinning on his head,” Still says matter-of-factly. “He doesn’t really do anything else, and to be honest, he’s not that good at any other moves.”

Koreans, in other words, are really good at repetition. “Everyone has a theory about why Koreans are dominant at short track,” Simon Cho, a retired Korean-American skater who competed in the 2010 Olympics in Vancouver, told me. “What it really comes down to is early discipline — Korean skaters are technically trained from a very early age.” This was a life Cho knew intimately as an immigrant whose family moved to the States when he was a young boy. His father saw the growing Korean success in short track and put his son in skates when he was 3. As Cho progressed, he was coached by a series of Korean coaches accustomed to a ruthless national athletic program that winnowed down a vast pool of young skaters through a steady diet of corporal punishment and repetition that set the hips deeper into crouches, the shoulders leaning at the correct angle, the thighs pumping with precision. Cho was beaten with hockey sticks and forced to run endless laps by his Korean coaches, and when he was ultimately suspended from the sport for tampering with a Canadian competitor’s blade, he said his Korean coach had put him up to it.

Those Korean coaches who showed up in the States in the ’90s and ’00s brought with them an idea of competition forged through decades of rapid economic development after a war that destroyed the country and ripped families apart. “That period in history made Koreans an overzealously proud people,” Benson Lee, the director of “Planet B-Boy,” says. “That competitiveness comes from this idea of han — a deep-rooted desire to be a contender because of missed opportunities and being driven to succeed because you suffered so much.”

Immigrants tend to cling to these sorts of cultural explanations, perhaps out of unrequited homesickness. We second-generation immigrants who see our motherlands only through spectacles like Olympic competitions are usually disappointed by the realities behind them. But that’s what allows a hybrid identity to emerge, one more attuned to our new homes. Cho believes that he — or really any American skater — would not have been able to compete on the world stage without Korean instruction, but he also believes there’s another way. He now coaches in Maryland; many of his skaters are the kids of second-generation Korean-Americans who were brought up in the States. Some have been punished in the old ways by previous coaches, but others are only vaguely aware of what Cho and his generation of skaters experienced. Parents “would be horrified if I coached their kids the way I was coached,” Cho says. “That’s gotta be progress, right?”

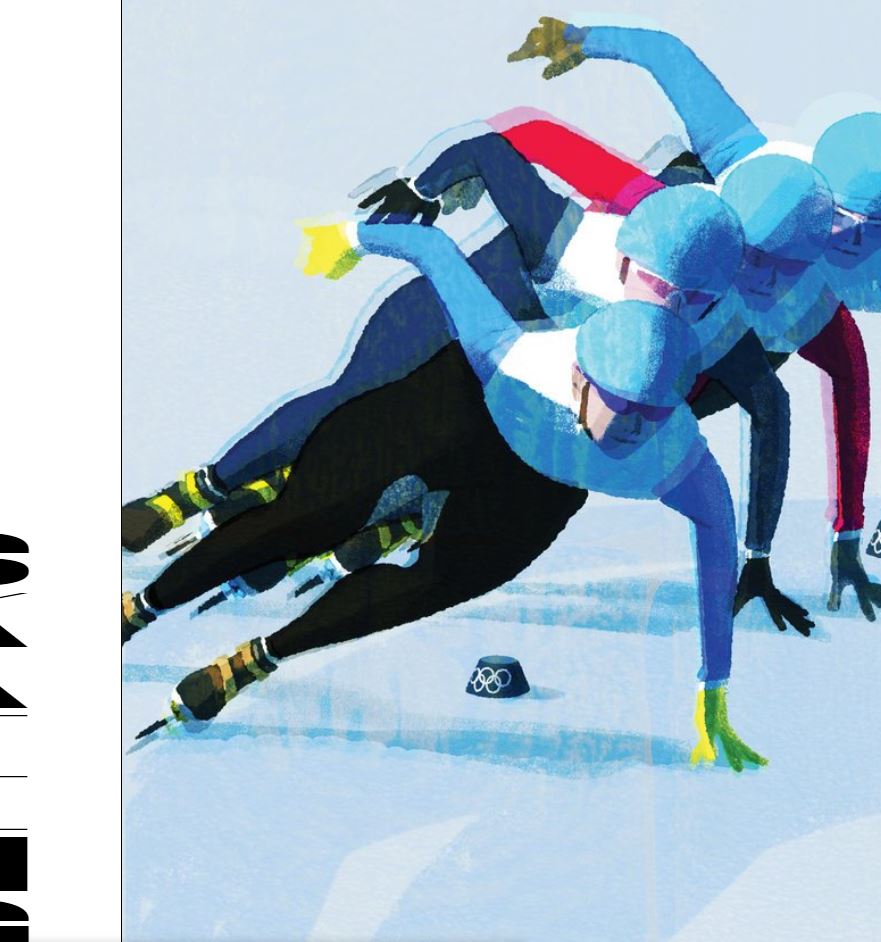

Jay Caspian Kang is a writer at large for the magazine. He last wrote about the insurgent media company Barstool Sports. Tatsuro Kiuchi is an illustrator and a painter based in Tokyo who is known for illustrated children’s books and advertisement work.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week.

WINTEROLYMPICS2018

MORE IN THIS ISSUE

The Workout That Saves Lindsey Vonn From Wipeouts

Want to Launch Yourself Off a 4-Meter Ramp Like a Freestyle-Skiing Olympian?

If Curling Can Make It in Tampa, It Can Make It Everywhere

Once Prohibited, Women’s Ski Jumping Is Set to Take Flight

The Hidden Drama of Speedskating

The Unabashed Beauty of Jason Brown on Ice

The Search for Stillness at the Heart of Biathlon

The First African Team to Compete in Bobsled

Why Koreans Are So Good at Speedskating

What Cross-Country Skiing Reveals About the Human Condition

The Lonely Mission of India’s Sole Luger

Why Skeleton Racing Is So Brutal on the Body

The Remaking of the Hockey Goalkeeper

‘Big-Air Snowboarding’ to Make Its Big Olympic Debut

Gearing Up in Nordic Combined

No comments:

Post a Comment