Opinion

State of the Culture, Part I: Museums, ‘Experiences,’ and the Year of Big Fun Art

In a look back on the epochal shifts we experienced in art and culture in 2017, Ben Davis explains how we got to the odd place we are today.

Last year, the day after the election, the headline of the New York Timesblared “TRUMP TRIUMPHS.” Below the fold, another story was teased beneath the heading “FAILED PREDICTIONS,” whispering something else: “Media Didn’t See It Coming.”

As I tried to imagine what to say about this intense year, I thought of that. In 2017, the political outrages were so many and so battering that it’s easy to lose track of the ways that basic assumptions about how art functions are changing. Without some assessment of the latter, it’s hard to know if art is properly responding to the moment at all. With all of the flashes of controversy in the air, we may miss the larger, slower, destabilizing tectonic shift underfoot.

In other words: We may not see it coming, again.

So I thought I would end the year with some reflections on the shifting art-and-media landscape, and how it is affecting museums, artists, and critics. Here we go.

A Bit of History

What are the conditions under which art reaches a broad audience today? Museums are probably the biggest stage for art. How are they faring?

The idea of art as a popular spectacle has a complex history. In the 1800s, when painting was still far more advanced than photography in its ability to convey the detail of the world, huge crowds could turn out for artists like Turner, Church, or Géricault, whose large-scale canvasses served as the IMAX entertainment of the day.

But then, in the 19th century, the opposition between highbrow and lowbrow culture was still solidifying.

Fredric Edwin Church, Heart of the Andes (1859), from the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection.

The church-like atmosphere that came to characterize modern museum culture was designed specifically to be anything but populist. The preciousness of the “white cube,” as Brian O’Doherty famously termed the space of the modern gallery space, had an embedded message: “Esthetics are turned into a kind of social elitism.”

And so, the demands of radical art activists in the anti-establishment ’60s focused on making the museum less aristocratic, more accessible to a wide-ranging audience. In that sense, the idea of the truly mass-appeal museum is recent-ish—born yesterday, in art-historical time—and is thus still evolving.

In the 1966 essay on “The Historical Function of the Museum,” the art critic John Berger recounted a scheme proposed by an unnamed “French curator” in a then-recent book. “[T]he museum of the future will be mechanized: the visitors will sit still in little viewing boxes and the canvases will appear before them on a kind of vertical escalator. ‘In this way [the curator wrote], in one hour and a half, a thousand visitors will be able to see a thousand paintings without leaving their seats.’”

In the ‘70s, the highly hyped and merchandized “blockbuster” exhibition arrived, and museum culture began to dance to the tune of “King Tut”. Trying to justify their existence amid the changing, post-’60s culture, as the less buttoned-down Baby Boomer sensibilities went mainstream, museums (or those museums that had the budget) turned towards touring spectacles to draw big crowds.

Queues for the “Treasures of Tutankhamun” exhibition outside the British Museum, London, April 1, 1972. Photo by Steve Wood/Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

“The capitalist achievement does not typically consist in providing more silk stockings for queens but in bringing them within reach of factory girls,” libertarian bard Joseph Schumpeter once famously said. When art observers repeat the demand, today, that we bring “art into life” or bring “art to the masses” (or “make art as popular as music”), this missionary imperative seems to me to ignore the degree to which that particular demand has already been fulfilled, just not in the form that people imagined.

“Art for the masses” already achieved a consumerist fulfillment in the museum gift shop: A poster in every dorm room, a print for every price point. As for the technological populism, envisioned by Berger’s curator, it was prophetic not of the solution to museums’ popular educational mission, but of the new challenges facing that mission that arrived in recent years.

From the Touring Blockbuster to the Mobile Internet

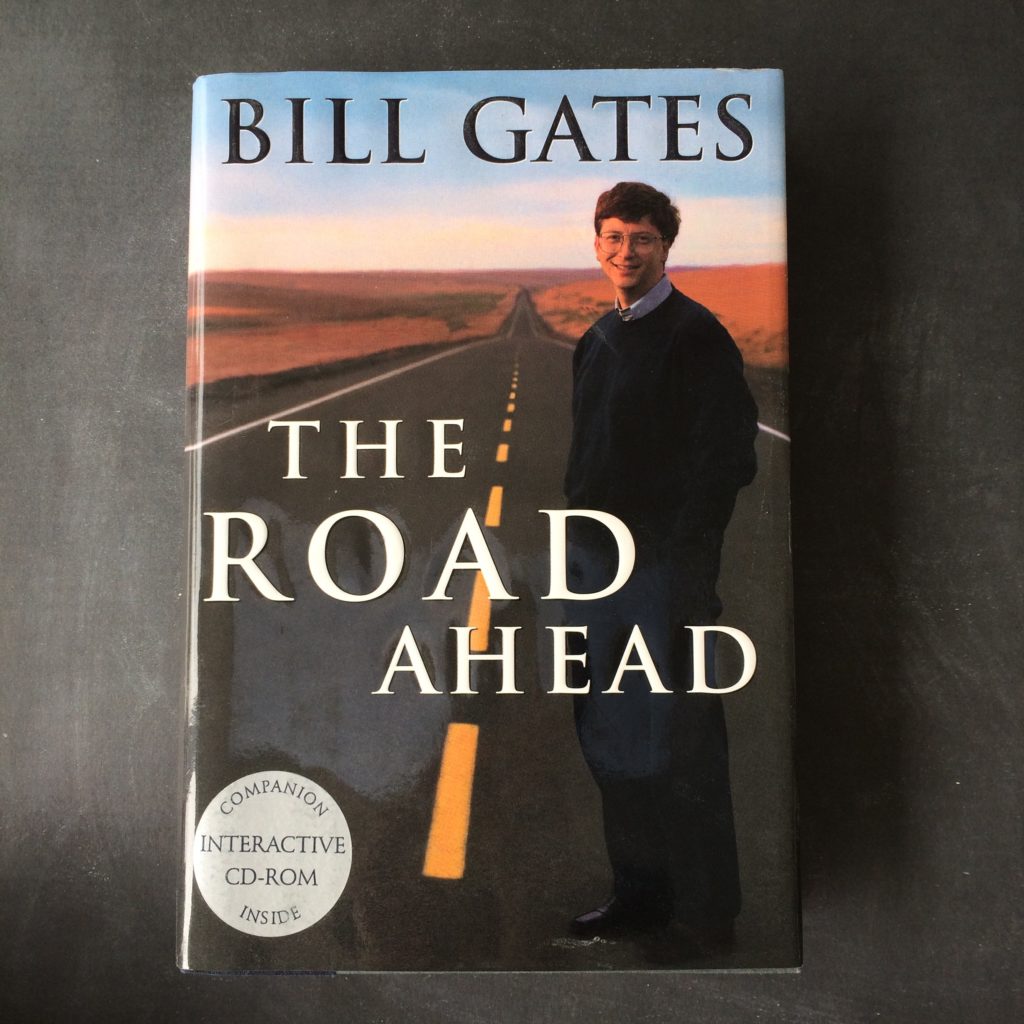

In 1995, Bill Gates released his autobiography, The Road Ahead. In it, he imagined a device called Interactive Home Systems, which would fulfill the functions of the encyclopedic museum—but now as home entertainment. It resembled, in its prototype form in the Gates household, a bank of Nam June Paik-esque TV monitors.

“If you’re a guest,” Gates wrote, “you’ll be able to call up portraits of presidents, pictures of sunsets, airplanes, skiing in the Andes, a rare French stamp, the Beatles in 1965, or reproductions of High Renaissance paintings, on screens throughout the house.”

This scheme foretold the collapse of different levels of culture into a single, on-demand media space—but it was still out-there stuff in the ’90s. The idea didn’t catch on. Eventually Interactive Home Systems was rebranded as Corbis, the stock photo archive, later purchased by Getty Images.

Two years later, when internet-based art was first inserted into a major art show, at documenta X, curators faced the problem of how to present it. They settled on an office-like environment of dedicated computer stations. At the time, this alien presence caused a prophetic shiver of anxiety to run through the space. As Domenic Quaranta explains, “the internet connection was often seen as an open invitation to the user to leave the work, go and check her email, or, even worse, to freely surf the internet.”

A little more than a decade later, Apple launched the iPhone, referred to at the time as the “God Device.” Now, another 10 years later still, the god-like capacities of the mobile internet have become such a boring, banal fact that it is hard to recall that something like it was envisioned as a utopian outcome for culture not so long ago.

Banal—but very alluring as an aesthetic object: The average person supposedly touches their phone more than 2,600 times a day. Whatever is in front of you, there is always a potentially more interesting thing available at the swipe of a finger—French stamps, Renaissance paintings, candy-based slot machine apps, whatever—with social consequences we all know (have you “phubbed” someone lately?). It’s an encyclopedic museum in every pocket.

As a result, the public is ever more encased in some form of culture or other at all times, at levels that weren’t imagined five years ago, let alone 50. This year, the average American adult consumed more than 12 hours of media a day, a staggering total only made possible by the fact that people are often consuming multiple streams at once. There are mobile video games designed to occupy bursts of as little as three seconds of your free time.

Art, in other words, has embedded itself pretty deeply into life.

The Culture Industry Begins to Deindustrialize

When people talk about “blockbuster” museum shows, they draw on the language of Hollywood, the archetypical “culture industry” of Horkheimer & Adorno’s apocalyptic tract on the commodification of aesthetic experience, Dialectic of Enlightenment. Blockbuster franchise cinema appeared on the scene at roughly the same time that “The Treasures of Tutankhamun” was touring the world, inaugurating the museum blockbuster, in the ’70s: Jawshit cinemas in 1975; Star Wars, 1977.

Well, what is the state of blockbuster cinema today? Have you noticed that Hollywood is in trouble? It is. Fewer and fewer people are going to see cinema, as the moviegoing experience is beset by competition from steaming services and video games and social media.

Stormtroopers pose at the red carpet for the Chinese premiere of ‘Star Wars: The Last Jedi’ at the Shanghai Disney Resort in Shanghai on December 20, 2017. Image courtesy Chandan Khanna/AFP/Getty Images.

The internationalization of the film market and rising ticket prices keep the industry afloat. But, as a result, character-based mid-budget movies have all but ceased to matter in theaters, while the war for your attention is commanded by tentpole franchise films aimed at the broadest possible audience, armed with the most iconic IP (Star Wars, Marvel, and Pixar, to name only the ones Disney owns) and propelled by marketing budgets in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

This stratified dynamic definitely finds an echo in the gallery scene, where the biggest gallery chains and fairs are consolidating a hold over event-driven art crowds. Smaller galleries weigh whether it is even worth it to maintain a physical space, as foot traffic dries up. Record-setting blockbuster museum shows in tourist capitals and splashy new private museums have emerged parallel to a now decades-long erosion in the audience for the fine arts.

A Big Fun Year

Last year, I visited Meow Wolf, an art (or para-art) experience in Santa Fe, New Mexico, partly funded by George R. R. Martin. The brainchild of a collective of talented artists, it is very successful and amounts to an interactive haunted house, full of tricks and tactile attractions and eye-popping props, with a pulpy sci-fi backstory that you could unravel upon repeat visits.

Outside of Meow Wolf in Santa Fe.

It was impressive, and bound by dint of its popularity to be influential. I thought we needed a name for what it represented, to take it seriously as a trend, and I proposed Big Fun Art. At the time, I said, “this kind of art’s influence is likely going to spread quickly from the margins, putting pressures on museums to embrace it or define themselves against it.” The year since has proved that hypothesis, in spades.

Meow Wolf’s creators had theorized what they were doing, arriving at their attraction by studying what worked in the larger contemporary museum ecology. “What we did was focus on kids, because the admissions-based market is driven by kids,” Meow Wolf frontman Vince Kadlubek told Albuquerque Business First. “We also didn’t want to alienate adults and teenagers so we still stayed true with very mature themes inside our exhibit.”

A mysterious beast, an attraction at Meow Wolf. Image: Ben Davis.

For its part, Meow Wolf structures its environment around the same kind of popcorn sci-fi narrative that undergirds the present-day blockbuster movie economy. It’s fantastical, but familiarly archetypical enough to tap into a broad audience.

In its Google search index, Meow Wolf puts the words “Immersive Art Installation” even before its own name. In the end, a sense of you-have-to-have-been-there immersion is its most important draw. Meow Wolf, in effect, offers a fabulated cabinet of curiosities, all of it designed to be very photogenic.

Sharing photos of things has now become the main driver of the outside-the-home experience economy, with design implications for everything from restaurants to architecture to vacation resorts, which are being reworked around the principle. This year, social media advertising became more important channel to reach culture consumers than print, according to Culture Track.

Not long ago, museums were trying to curb phone use and picture-taking. Now museums beg audiences to share their shows under dedicated hashtags, the vast majority of which fall comically flat in the virtual scrum.

This year, the Takashi Murakami show at the MFA Boston offered this label, which says it all:

A Kusama Sundae

Another name for the Big Fun Art phenomenon might be Kusamafication.

The Hirshhorn leveraged the mania around Yayoi Kusama‘s mirror rooms to increase its membership by 6,000 percent—so of course other attention-starved institutions are realizing that their future is intimately bound up in catching the viral social media wave too. In LA, so ardent were the crowds looking to share a photo from the storied Japanese artist’s installations that the Broad Museum instituted a 30-second rule for the actual in-person experience, which is about just enough time to snap a decent picture.

Yayoi Kusama at David Zwirner, 2017. Photo: Sarah Cascone.

The genre-blurring of postmodern art was rooted in Marcel Duchamp’s hostility to “retinal” art. How funny, then, that conceptualism yielded up “relational aesthetics” and various forms of new-media installation, which then, in turn, have merged together with the more powerful interactive capacities of the smartphone to create a new form of art that is pretty much the ultimate in “ocularcentrism”: art environment as photo backdrop, aka “selfie factories.”

Big Fun Art doesn’t require any historical knowledge, context, or even patience to be enjoyed (except the patience of waiting in a line). On the other hand, that also means you don’t really need something like a museum to vouchsafe it.

An installation from Juicy Couture at 29Rooms. Courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

The war for relevance in the “attention economy” hits new heights. Branded experiences (like the art/sponsored-content hybrid known as “29 Rooms,” from Refinery29) compete with retail spaces looking to refashion themselves as “experiences” to get some advantage over online shopping (Behold Yankee Candle’s “Candle Power” exhibition). These in turn compete with the various new para-art pop-ups that now go head to head with museums for the adult theme-park dollar.

Here’s how that Culture Track study summed up the trends facing museums this year: “For today’s audiences, the definition of culture has democratized, nearly to the point of extinction. It’s no longer about high versus low or culture versus entertainment; it’s about relevance or irrelevance. Activities that have traditionally been considered culture and those that haven’t are now on a level playing field.”

Such cultural flattening echoes the effects of capitalist globalization and information technology on labor markets, where the “disruption” of old ways is pushed as a dogma and local borders no longer defend workers from competition from half a world away.

In 2017, facing the headwinds of audience indifference, the Indianapolis Museum of Art cannily rebranded itself as Newfields: A Place for Nature and the Arts. The refreshed identity promotes the institution less as an arc of timeless culture and more as a hub for experiences, focusing on attractions like artist-designed mini-golf, a beer garden, Christmas light shows, and its outdoor nature park.

The Museum of Ice Cream Miami. Photo courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

That’s the highbrow version of the trend. As Newfields ditched the “museum” label, the touring juggernaut that is the Museum of Ice Cream has colonized it, and has already been hailed as the pop-up millennial answer to Disneyland. It is an attraction that quite literally aspires to be the visual equivalent of junk food, featuring various ice cream-themed environments tailor-made for selfies. It is a very, very serious force to be reckoned with, rivaling the popularity of actual museums in any city it lands in.

At year’s end, Instagram said that it was the 10th most photographed museum in the world, already in the same league as the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Mona Lisa on the same level as a pool filled with plastic ice cream toppings.

Revolution in the Air

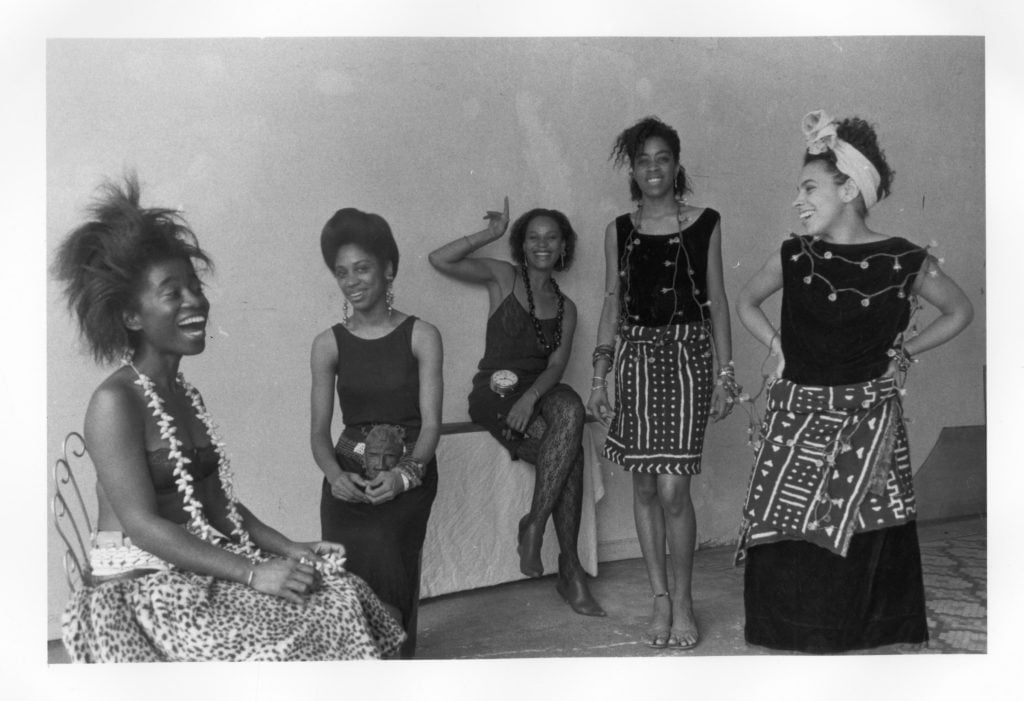

Were there very good shows this year that pointed a different way? Oh yes, absolutely. “We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–1985” at the Brooklyn Museum was its own kind of new-model blockbuster. Surfacing history that hadn’t been given its due, it has the potential to have powerful aftershocks, opening up the canon and speaking to new audiences.

“We Wanted a Revolution” affirmed what museums can do at their scholarly best. It had important discoveries. It had a mission. It also packed in a ton of history and context. The crowds that came out for it were definitely there for more than a 30 second photo op.

Lorna Simpson, Rodeo Caldonia (Left to Right: Alva Rogers, Sandye Wilson, Candace Hamilton, Derin Young, Lisa Jones) (1986), as seen in “We Wanted a Revolution.” © 1986 Lorna Simpson

Such a show takes time and resources, faith in an audience’s intelligence, and careful thought about how the past informs the present. Maybe museums can balance both that mission and the other pressure—but the centrifugal pressures on art institutions are only increasing as the attention space grows more crowded.

“As the world bifurcates into fast and slow lanes, museums will have to find temporal or spatial ways to accommodate different paces,” the Center for the Future of Museums warned, already a few years ago now.

The Museum of Ice Cream Miami. Photo courtesy of Sarah Cascone.

But, look, to be clear: The Museum of Ice Cream and its ilk aren’t the End of Culture. Fun things aren’t bad. Everyone likes a good milkshake once in a while. Milkshakes bring people together. And if you were taking your 13-year-old niece or nephew to something, you might suck it up and pay the $38 for the Museum of Ice Cream rather than the $25 for the Museum of Modern Art. But if your only plan to feed your nephew is to give him milkshakes, you are in trouble.

How do museums navigate, productively, the Big Fun Art present? To rise to that challenge, they need the vision of artists and the support of critics. What this year offered those two constituencies, I will tackle next time.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

Article topics

No comments:

Post a Comment