Coined by Thomas More in 1516, the word “utopia” stems from the Greek ou-topos—which means “no place” or “nowhere”—but also refers to eu-topos, meaning “a good place.” The very origins of the word therefore reflect the question of whether a good or perfect place can ever exist. Throughout history, religious reformers and visionary starchitects alike have attempted to answer that question by establishing spiritual communes and crafting masterplans for cities of the future. Below, we highlight seven that didn’t quite pan out.

Palmanova, Italy

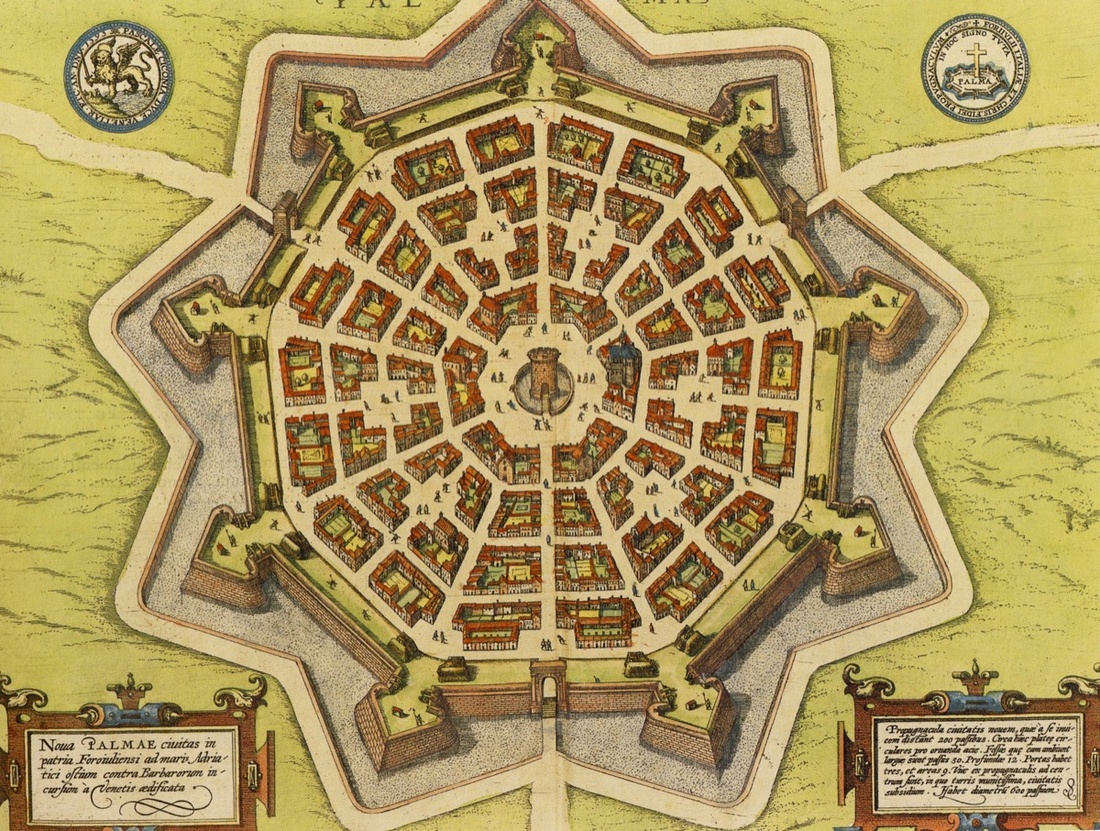

The Venetian model city of Palmanova from Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg, 1572-1680.

Built strategically near what is now the Slovenian border to defend against the Ottoman Empire in the late 16th century, the fortress city of Palmanova boasted some of the era’s most cutting-edge military features, including nine protruding ramparts as well as a surrounding moat and three guarded entryways. Its harmonious radial symmetry was intended to reflect the goodness of its incoming inhabitants—except no one actually wanted the risk of living in what was essentially a military citadel. Eventually, the Venetian government pardoned prisoners and gave them property in the city to fill its street. Today, Palmanova is home to about 5,400 residents.

Arcosanti, Arizona

Photo by arcosanti apse, via Flickr.

The sign at the entrance of Arcosanti, in the middle of the Arizona desert, reads: “If you are truly concerned about the problems of pollution, waste, energy depletion, land, water, air and biological conservation, poverty, segregation, intolerance, population containment, fear and disillusionment, join us.” Founded in 1970, the town is the brainchild of Italian architect Paolo Soleri, who envisioned a multi-story housing complex for 5,000 people. There, they would grow their own food, bring no harm to the environment, and support themselves by producing and selling windchimes. Expected to be completed within five years, the town today is three percent complete, though a cohort of about 50 residents continues to cast and carve away at bells in the “New Age crafts retreat,” as The Guardian called it.

Ordos, China

Photo by @matt_e_, via Instagram.

Hundreds of hastily constructed yet nearly uninhabited “ghost towns” have cropped up across China in the past few decades as the country sees unprecedented economic growth and real estate development. New Ordos, located just south of Old Ordos in Inner Mongolia, is one extreme example. In the early 2000s, the Chinese government invested billions of dollars to construct the supercity on bare land in the Gobi Desert. The larger-than-life architectural projects include a huge statue of Genghis Khan overlooking its central plaza, and “Ordos 100,” a now-terminated project by Ai Weiwei and Herzog & de Meuron, featuring 100 villas designed by architects from around the world. Yet the tremendous cost of building the city resulted in some of the country’s highest property values—second only to Shanghai—so, unsurprisingly, few wanted to move in. As photographer Raphael Olivier said following his visit, “The whole place feels like a post-apocalyptic space station from a science-fiction movie.”

Drop City, Colorado

Photo by Clark Richert.

In the spring of 1965, three college graduates bought six acres of land in southern Colorado. It cost $450. There, they established Drop City, a community in which punishment was prohibited, meals were communally prepared, and property was shared among all. For a little while, the inhabitants of this early “hippie commune” all got along: They planted gardens, raised chickens, made art, and built their signature geodesic dome residences from recycled materials. Drop City’s death bell starting ringing in early 1967, when one particularly unruly member proposed hosting a “Joy Fest” for music and art. As the number of residents—and the use of illegal drugs—escalated, members began abusing the communal funds for personal goods. Finding it increasingly difficult to stick to their no-punishment rule, the founders eventually gave up and abandoned their utopian dream.

Le Corbusier’s Radiant City

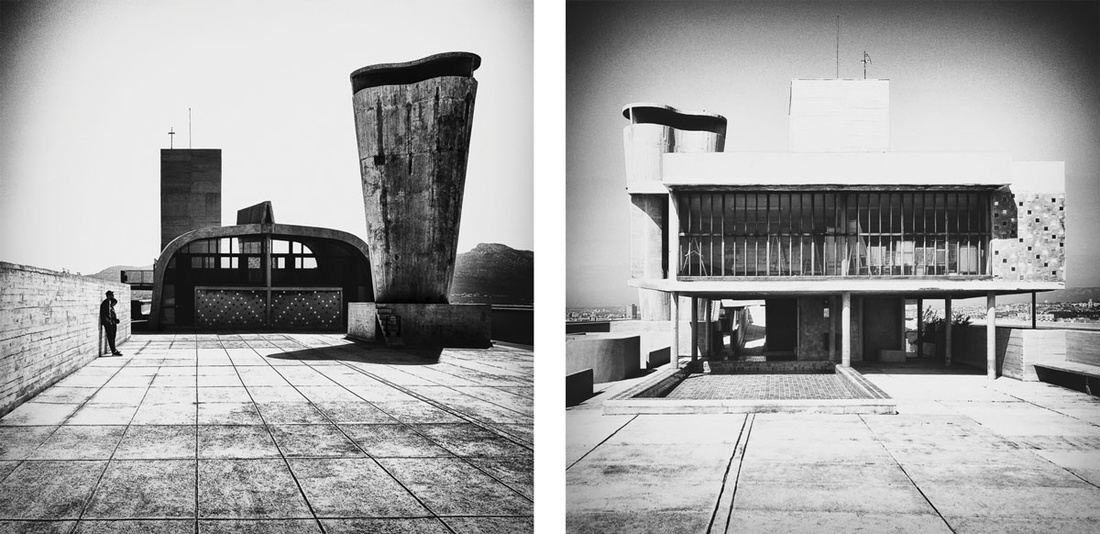

Photos by Napafloma-Photographe, via Flickr.

Presented in 1924, Le Corbusier’s plan for the Ville Radieuse (Radiant City) never actually came to fruition—though many of its principles went on to influence modern planning and urban housing complexes across the globe. The city was to operate as a “living machine”: Different areas would be designated for commercial, business, leisure, and residential purposes; a transportation deck in the city center would connect city dwellers, via underground trains, to housing districts consisting of towering premade buildings called “Unités.” Though it was envisioned as a utopian city, modern-day manifestations of Corbusier’s ideas have drawn criticism for their lack of public spaces and a general disregard for livability. Unité-like apartment complexes on urban fringes are now subject to high levels of poverty and crime.

Auroville, India

Photo by ccarlstead, via Flickr.

Established in 1968 by Mirra Alfassa, a French woman known as “the Mother,” Auroville (“the City of Dawn”) is the world’s largest spiritual utopia. A four-point charter outlines its founding ideals, including that it “belongs to humanity as a whole” and that it will be “a place of an unending education, of constant progress, and a youth that never ages.” Its labyrinthine, circular plan is anchored by the central “Matrimandir,” a huge dome covered in gold plates. Protected by UNESCO and supported by the Indian government, Auroville is today home to 2,500 people, and it seems to be in good shape—though its idealistic reputation has been undermined by questions of who controls its funds and whether its rules are actually followed. Crime and corruption are significant problems, too.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City

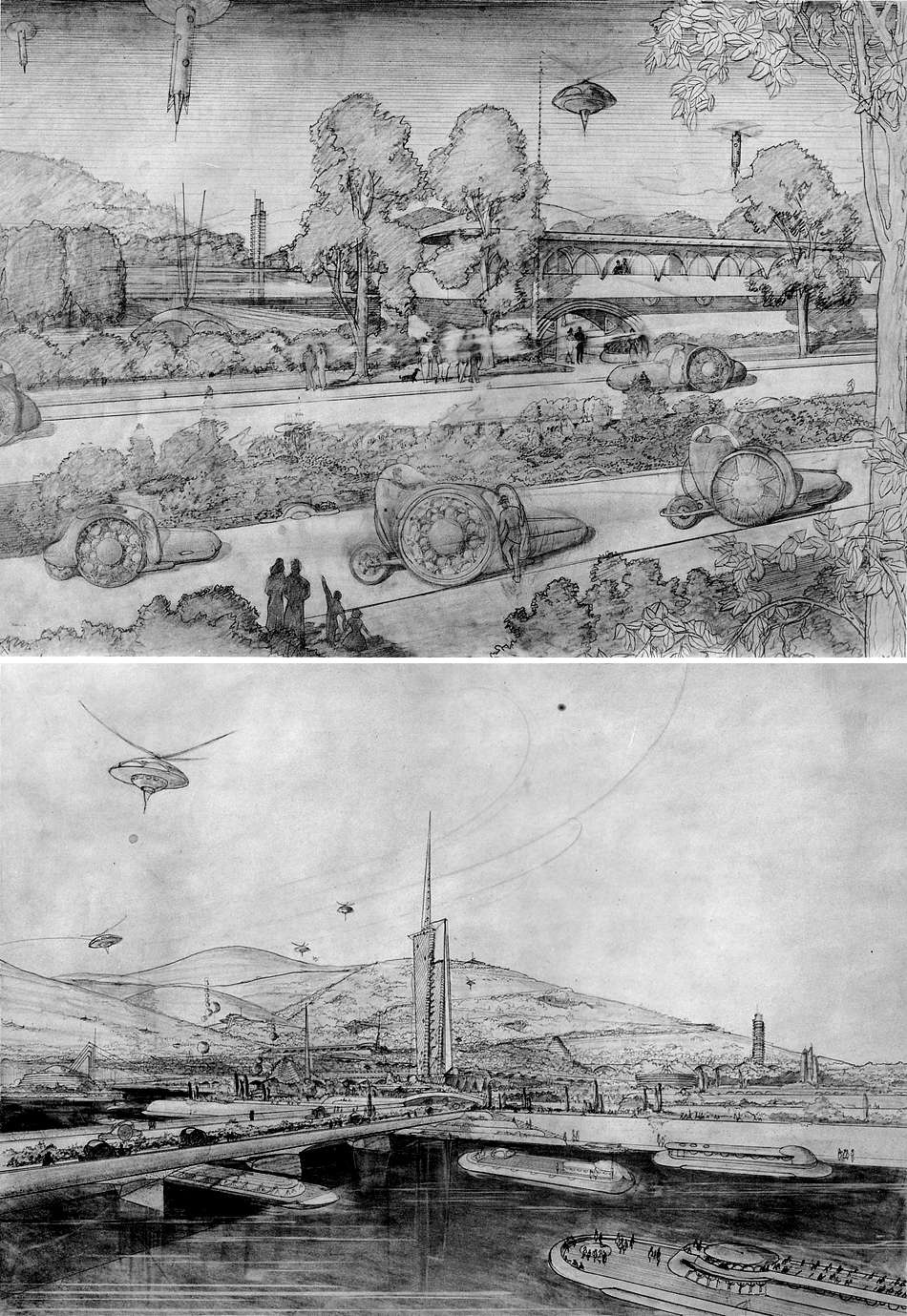

Photo by Kjell Olsen, via Wikimedia Commons.

Le Corbusier’s nemesis and fellow starchitect envisioned a different city for America—one that resembled more of a cookie-cutter suburb than a bustling metropolis, with more open space and sprawling landscape than skyscrapers. His city was based on modern technologies found in the automobile, electronic communication, and standardized mechanical production; everything from the size of roads to the proximity of schools and commerce would be based on “a new standard of space measurement—the man seated in his automobile.” However, Wright’s contemporaries found his plan wasteful and egotistical. Art historian Meyer Schapiro deemed it “perfectly consistent with physical and spiritual decay.”

—Demie Kim

No comments:

Post a Comment