Art and Law

The Year of the Fake: The 8 Biggest Forgery Controversies of 2016

The most ridiculous—and expensive—fake art scandals and spats of the year.

Fakes and forgeries in the art world are the stuff of legend, the subject of books, films, and television series the world over. In real life, they land people behind bars. 2016 brought us many unwanted things, but it also appears to have been a year when a huge amount of authenticity disputes took place. The spats took shape from contested provenance, to painters faking their own work, to a multimillion dollar Old Masters scandal. From farce to tragedy, we’ve compiled the highlights of this year’s biggest art forgery scandals below.

When a painting that appeared to be the long-lost second version of Judith Beheading Holofernes by Caravaggio turned up in an attic in France, the world was watching. Before the authenticity of the painting was even established, an unnamed American institution tried to put in an offer for the potential Baroque masterpiece.

The painting was claimed to be a fake by Caravaggio expert Mina Gregori, but in light of some recent mistakes on her part, judgement was still reserved. Then, expert Eric Turquin stepped in to authenticate and value the painting at €120 million.

While the authenticity of the painting remains unconfirmed, the “yeses” were enough for some. The work went on view to the public on November 10 at Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, to some outcry from the art community.

Lee Ufan poses near one of his artworks entitled “L’arche de Versailles” (‘The arch of Versailles’), on June 11, 2014. at the Chateau de Versailles, during the exhibition “Lee Ufan Versailles”. Photo courtesy Fred Dufour/AFP/Getty Images.

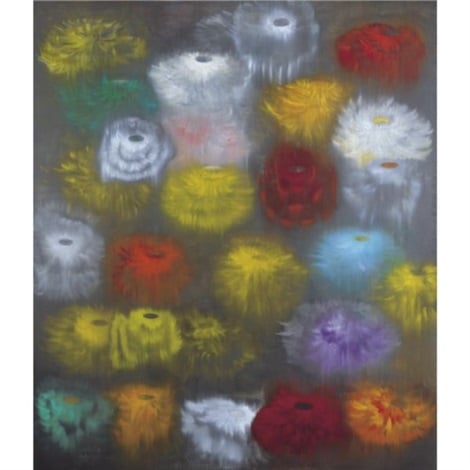

The forgery scandal surrounding the work of minimalist South Korean artist Lee Ufan was puzzling at best. In the first instance, the accused forger, known as Hyeon, confessed to police—only to have Ufan himself contradict him, verifying that thirteen alleged fakes were, in fact, genuine.

In an added twist, new charges were brought against a second Korean forgery ring. This involved a master forger known only as Park selling forgeries to a Seoul gallery for hundreds of thousands of dollars. The gallery, run by a husband and wife known as Kim and Ku, then sold them on for millions. Park confessed to forging a total of forty works.

The scandal led the Korean government to introduce new legislation to prevent the eruption of any more similar scandals. In the aftermath, however, all owners of Ufan’s work are undoubtedly checking their provenance.

Alexander Liberman, Agnes Martin with Level and Ladder (1960). Photography Archive, Getty Research Institute. Photo ©J. Paul Getty Trust.

The London-based Mayor Gallery launched legal action against the estate of Agnes Martin in October, after they refused to authenticate 13 works that the gallery had already sold. The potential costs were both the gallery’s reputation, and around $7.2 million in refunded sales.

The works in question were Night and Day, an untitled work, and eleven more works on paper.

In an added twist, Pace Gallery‘s Arne Glimcher was named in the suit because, as both the founder of the Agnes Martin Foundation and the owner of Pace, Glimcher could be involved in a conflict of interest, which could void the estate’s rejection of the works.

If the case finds in favor of the estate—which is the most common result in cases such as these—the works will be rendered valueless. The gallery, which has already refunded two of the three clients involved, would have to refund its third client in this matter to the tune of millions.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Venus (1531). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The image of the dapper crook knocking out Raphaels in a garret, secretly making millions, is fodder for many a Hollywood script, but it’s most fascinating because it really happens. This summer, a multi-million dollar forgery scam came to a head around the first iteration of TEFAF New York.

In a hot mess that drew in everyone from European Royalty to London’s National Gallery, forgeries of work by 25 Old Masters totalling an estimated $225 million were brought to the market by the French dealer Giulano Ruffini.

The scandal kicked off with the high drama of French authorities seizing Venus by Lucas Cranach the Elder—owned by the Prince of Liechtenstein—from the Caumont Centre d’Art in Aix, and spread through the art world like wildfire, taking Orazio Gentileschi’s David with the Head of Goliath, and Velázquez’s Portrait of Cardinal Borgia with it, calling the authenticity of the Old Master works into question.

The original source of the suspected forgeries is a mystery, although they were of such a high standard that they passed muster at such prestigious institutions as Christie’s, The Met, and the aforementioned National Gallery.

Ross Bleckner, Sea and Mirror (1996). Image courtesy Artnet.

This has all the elements of a classic New York art world spat. From celebrity and art world royalty, to in-court name calling and accusations of interstate tax evasion, this case had it all.

The crux of the matter is that Alec Baldwin claims he thought be was buying the original work Sea and Mirror (1996) by Ross Bleckner, whereas Boone claims he always knew the work would be a copy, painted for Baldwin by the artist.

The case rumbles on, but pinnacles so far have included Baldwin likening Boone to a bank robber in a court of law, and Boone trying to have the case thrown out of court on the grounds that Baldwin had the work shipped to LA, and then New York, to avoid paying sales tax. The saga continues.

A suite of four Louis XVI gilt-walnut armchairs stamped by Louis Delanois that sold at Christie’s Paris in 2015.

These pesky forgers don’t limit their scams to painting, and are capable of turning their hands to many types of fakery. In the case of this set of six Louis XIV chairs—sold by highly-respected Parisian antiques dealer Kraemer Gallery to the Palace of Versailles itself—it emerged after the sale was made public that there just were not as many chairs in the court of Versailles as there are currently in circulation. The natural conclusion would be that some of the presumed authentic chairs must indeed be fakes.

The authenticity of the chairs is still under investigation by the French authorities, but the scandal attached to the story led the respected Kraemer Gallery to drop out of of the Biennale des Antiquaires.

Lawrence Ulvi. Photo courtesy Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office.

Lawrence Ulvi spent years running a tidy little business in fakes of the Northwest School, including works by Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, and Kenneth Callahan.

Ulvi had been knocking out and selling these works to galleries in Canada and the US since 2008, netting himself a cool $66,232 in the process.

Once caught, the artist’s lawyer pleaded for no prison term on the grounds of ill health. Facing a maximum sentence of twenty years, the presiding judge did offer some leniency to the forger, sentencing him to one year and one day in prison, and encouraging him to bring his paintbrushes and artistic talent with him behind bars.

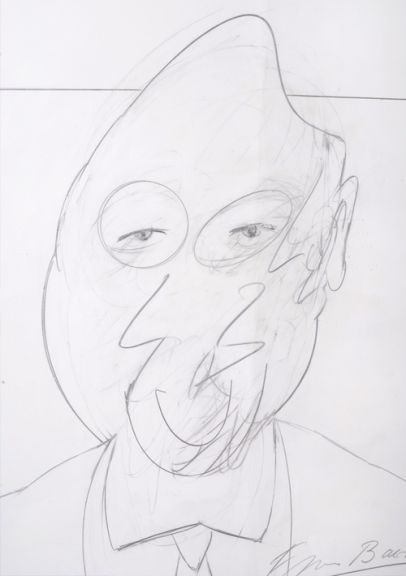

Drawing signed Francis Bacon. Photo courtesy Herrick Gallery.

8. Fakon

Fakon: Fake Bacon. Francis Bacon made it notoriously difficult to authenticate his work, by refusing to take part in the compilation of his catalogue raisonné or speak to those entrusted with the task.

That being said, when these gems (see above) came onto the market via an ex-boyfriend of Bacon, they were rejected from the catalogue raisonné before going up for sale at a London gallery. Just looking at these loose sketches, one is forced to consider—even if Bacon himself did make them—whether he would ever want them to see the light of day.

Follow artnet News on Facebook.

SHARE

Article topics

No comments:

Post a Comment