A Brief History of the Artist’s Studio

It

was 2 a.m. when the skies of Paris opened over Claude Lantier. Dashing

through the rain, the gifted but impatient painter arrived at his studio

facing the river Seine to discover a young woman seeking shelter from

the storm. After weathering the downpour inside—she on the bed, he on

the couch—Claude awoke to find the woman asleep, covered in little else

but sunlight. Inspired, the artist began to sketch his unconsenting

model, quietly, attentively, until she woke herself and discovered him

in the act.

So begins the 1886 novel The Masterpiece by Émile Zola, a fictional portrait of a tortured Impressionist painter. Drawing on the bohemian trappings of 19th-century Paris, the lives of a number of French artists, and male fantasies that entwine creative talent with sex and power, Zola’s text offers what is now a stereotypical vision of the artist’s studio as the locus of creativity—one that persists (if to a lesser degree) today. So why does the artist’s studio still hold such magnetism, and what can we learn from studying an artist’s workspace?

The studio of Paul Cézanne, one of the most influential painters in history and a primary source for the fictitious Claude Lantier, is still preserved today. Nestled on a hill in the South of France, with an airy view of Mont Sainte-Victoire, the studio is maintained by the government of Aix-en-Provence, with scores of the artist’s accoutrements on display. And Cézanne’s is just one in the constellation of studios that welcomes visitors each year. Other noteworthy examples are the distinctive “Blue House” of the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City; the “Villa des Brillants,” which served as the sculptor Auguste Rodin’s studio and home on the outskirts of Paris; the recently opened Manhattan home of Louise Bourgeois; and the evolving performance and installation manifested in conceptual artist David Ireland’s house at 500 Capp Street in San Francisco.

So begins the 1886 novel The Masterpiece by Émile Zola, a fictional portrait of a tortured Impressionist painter. Drawing on the bohemian trappings of 19th-century Paris, the lives of a number of French artists, and male fantasies that entwine creative talent with sex and power, Zola’s text offers what is now a stereotypical vision of the artist’s studio as the locus of creativity—one that persists (if to a lesser degree) today. So why does the artist’s studio still hold such magnetism, and what can we learn from studying an artist’s workspace?

The studio of Paul Cézanne, one of the most influential painters in history and a primary source for the fictitious Claude Lantier, is still preserved today. Nestled on a hill in the South of France, with an airy view of Mont Sainte-Victoire, the studio is maintained by the government of Aix-en-Provence, with scores of the artist’s accoutrements on display. And Cézanne’s is just one in the constellation of studios that welcomes visitors each year. Other noteworthy examples are the distinctive “Blue House” of the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City; the “Villa des Brillants,” which served as the sculptor Auguste Rodin’s studio and home on the outskirts of Paris; the recently opened Manhattan home of Louise Bourgeois; and the evolving performance and installation manifested in conceptual artist David Ireland’s house at 500 Capp Street in San Francisco.

Though

Cézanne was more sympathetic than Zola’s protagonist, the alluring

mystique of the modern artist in his studio may have found its

archetypal expression in Pablo Picasso.

His most iconic portraits depict women in the studio, like those of

Dora Maar, his “private muse.” In 2001, the Cleveland Museum of Art

exhibition and accompanying catalogue Picasso: The Artist’s Studio explored the artist’s work in the context of his workspace. And the theme has endured; Picasso: In the Studio was the subject of a spring 2016 issue of the journal Cahiers d’Art and a show in its Paris gallery featuring previously unpublished photographs of the artist at work—where else?—in the studio.

The studio is where strange magic happens, as much for the artist’s imagination as for the public’s. It’s the conjuring place of new concepts, styles, or forms. Sometimes it even comes to be seen as sacred, a place where visitors become pilgrims to the altar of art. On the other hand, as the artist Joe Fig recently told me, it is also “a place where mundane tasks and very non-glamorous things go on.” A sculptor and painter, Fig has also authored two books of interviews, Inside the Painter’s Studio (2009) and Inside the Artist’s Studio (2015), that explore artists’ working habits and the places that nourish them. Both aim “to shed light on the real day-to-day process of the artist, the time, hard work, and persistence it takes to succeed,” as he explains.

The modern artist’s workspace has its roots in the Renaissance, when masters taught apprentices in workshops. By the 17th century, artists were inviting patrons into these spaces. In her celebrated book Rembrandt’s Enterprise: The Studio and the Market (1988), the art historian Svetlana Alpers argued that by selling works produced by studio assistants, the Dutch master exerted unprecedented control over the sale of his own work, effectively transforming the meaning and market value for paintings like The Jewish Bride (1665). Opening the studio turned out to be good business.

The studio is where strange magic happens, as much for the artist’s imagination as for the public’s. It’s the conjuring place of new concepts, styles, or forms. Sometimes it even comes to be seen as sacred, a place where visitors become pilgrims to the altar of art. On the other hand, as the artist Joe Fig recently told me, it is also “a place where mundane tasks and very non-glamorous things go on.” A sculptor and painter, Fig has also authored two books of interviews, Inside the Painter’s Studio (2009) and Inside the Artist’s Studio (2015), that explore artists’ working habits and the places that nourish them. Both aim “to shed light on the real day-to-day process of the artist, the time, hard work, and persistence it takes to succeed,” as he explains.

The modern artist’s workspace has its roots in the Renaissance, when masters taught apprentices in workshops. By the 17th century, artists were inviting patrons into these spaces. In her celebrated book Rembrandt’s Enterprise: The Studio and the Market (1988), the art historian Svetlana Alpers argued that by selling works produced by studio assistants, the Dutch master exerted unprecedented control over the sale of his own work, effectively transforming the meaning and market value for paintings like The Jewish Bride (1665). Opening the studio turned out to be good business.

The studio gradually evolved to become a kind of stage for the performance of

making art. By the 19th century, the growing arts community in the

United States had come to understand this theater of art as valuable

real estate. When completed in 1857, the Tenth Street Studio Building in

Manhattan became the first facility of its kind in the United States or

Europe. Built with the needs of artists (and their potential patrons)

in mind, the Studio Building became the epicenter of the American art

scene. Any painter worth their weight in salt had a space there,

including the most famous member of the so-called Hudson River School, Frederic Edwin Church.

Church recognized the benefits of using the studio to stage his work in dramatic ways. When he exhibited his monumental canvas Heart of the Andes (1859) in the Tenth Street Studio galleries, he requested that visiting members of the public bring opera glasses to pick out salient details from the large painting. And his audience consisted not only of the public; with other renowned artists like Albert Bierstadt, Winslow Homer, John LaFarge, and William Merritt Chase also renting space in the same building, it was a place for artists to cross-pollinate and measure themselves against one another.

While the Studio Building was pivotal for Church’s career, Olana, the name of his opulent home and studio overlooking the Hudson River Valley, is justly more famous. Drawing architectural inspiration from Greece and Persia, Church transformed the house into, in his words, “a feudal castle.” Part villa, part fortress, Olana was adorned with bright bands of color and filled with intriguing objects collected during his travels. Now officially named the Olana State Historic Site, it is a National Historic Landmark and still holds, among many other artworks, the final large study for Heart of the Andes.

Olana is also part of another preservation network: Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios (HAHS). Founded in 1999 under the National Trust for Historic Preservation, HAHS has grown to a coalition of more than 30 museums that were once the homes and working studios of American artists.

Church recognized the benefits of using the studio to stage his work in dramatic ways. When he exhibited his monumental canvas Heart of the Andes (1859) in the Tenth Street Studio galleries, he requested that visiting members of the public bring opera glasses to pick out salient details from the large painting. And his audience consisted not only of the public; with other renowned artists like Albert Bierstadt, Winslow Homer, John LaFarge, and William Merritt Chase also renting space in the same building, it was a place for artists to cross-pollinate and measure themselves against one another.

While the Studio Building was pivotal for Church’s career, Olana, the name of his opulent home and studio overlooking the Hudson River Valley, is justly more famous. Drawing architectural inspiration from Greece and Persia, Church transformed the house into, in his words, “a feudal castle.” Part villa, part fortress, Olana was adorned with bright bands of color and filled with intriguing objects collected during his travels. Now officially named the Olana State Historic Site, it is a National Historic Landmark and still holds, among many other artworks, the final large study for Heart of the Andes.

Olana is also part of another preservation network: Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios (HAHS). Founded in 1999 under the National Trust for Historic Preservation, HAHS has grown to a coalition of more than 30 museums that were once the homes and working studios of American artists.

Among

the legacies that HAHS helps to maintain are those of important but

lesser-known artists, such as Grace Carpenter Hudson (1865-1937), whose

modest craftsman-style home stands in the small town of Ukiah,

California, at the southern edge of the Mendocino National Forest. It

testifies to the lifetime Grace and her ethnologist husband Dr. John

Hudson spent representing and recording the lives of the local Pomo, an

indigenous people of coastal California. Hudson’s home and studio

effectively documents a period of Pomo cultural reconstruction following

massacres and dispossessions by the U.S. government, offering insights

into how European Americans tried to see Native Americans as the

frontier came to a close.

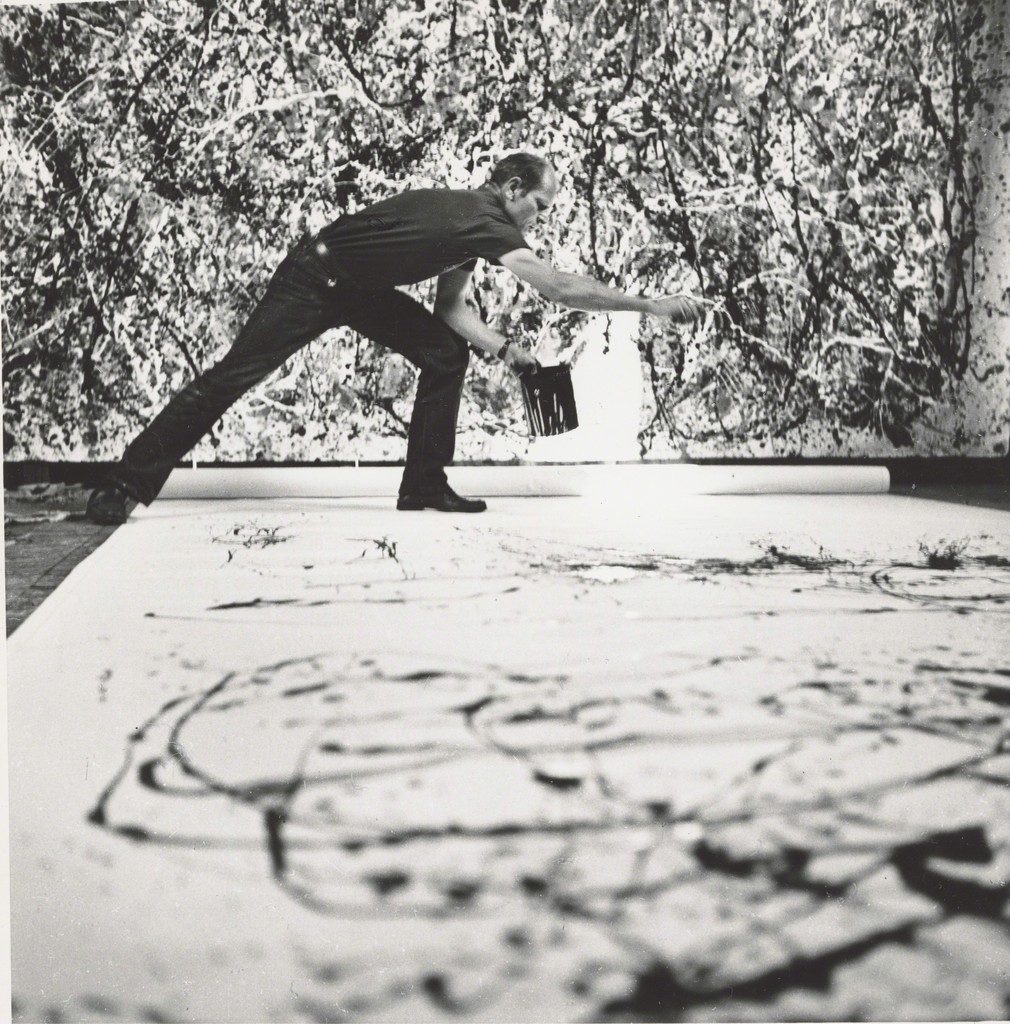

HAHS also counts studios of some of the most famous artists on its roster. After they married in 1945, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner moved from New York City to a small 19th-century fisherman’s home on Long Island’s East End. Although Pollock had already emerged as a leader of the Abstract Expressionist movement, a move away from the city—and the vices it whipped up—proved a needed change. It was there, in a converted barn, that Pollock made his legendary innovation: He began to pour, drip, and fling paint across canvases spread on the floor.

Helen Harrison, director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, says that the almost numinous quality of the place has been invaluable to other artists, filmmakers, and scholars. This is the very scene that Joe Fig painstakingly reproduced in miniature as part of his series of models of artists at work in their studios. It’s the historical setting that actor and director Ed Harris said was essential for filming the Oscar-winning biopic of the artist, Pollock. And it’s where documents stashed in a suitcase in the attic were discovered (in addition to several unpublished works on paper), shedding new light on Pollock’s and Krasner’s personal and professional lives. Pollock scholar Francis V. O’Connor says these discoveries represent the most gratifying moments of the ongoing work of preserving studios.

HAHS also counts studios of some of the most famous artists on its roster. After they married in 1945, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner moved from New York City to a small 19th-century fisherman’s home on Long Island’s East End. Although Pollock had already emerged as a leader of the Abstract Expressionist movement, a move away from the city—and the vices it whipped up—proved a needed change. It was there, in a converted barn, that Pollock made his legendary innovation: He began to pour, drip, and fling paint across canvases spread on the floor.

Helen Harrison, director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, says that the almost numinous quality of the place has been invaluable to other artists, filmmakers, and scholars. This is the very scene that Joe Fig painstakingly reproduced in miniature as part of his series of models of artists at work in their studios. It’s the historical setting that actor and director Ed Harris said was essential for filming the Oscar-winning biopic of the artist, Pollock. And it’s where documents stashed in a suitcase in the attic were discovered (in addition to several unpublished works on paper), shedding new light on Pollock’s and Krasner’s personal and professional lives. Pollock scholar Francis V. O’Connor says these discoveries represent the most gratifying moments of the ongoing work of preserving studios.

One

might also argue, of course, that the mythology of the studio as an

active creative force is another high modernist fantasy, one eroded by

the emergence of conceptual art in the 1960s. Robert Smithson

invoked Cézanne directly when describing the necessity of moving out of

the studio and into the world to make his site-specific land art. “We

now have to reintroduce a kind of physicality,” he insisted in an interview,

“the actual place rather than the tendency to decoration which is a

studio thing.” In his 1971 essay, “The Function of the Studio,” Daniel

Buren called the studio “purgatory,” a space of “ossification,” one that

John Baldessari would also later rail against in his “Post-Studio Art” class at CalArts.

For these artists, the post-studio practice was as much a political stance as an aesthetic one, an attempt to dissolve the constrictive joints between studio, gallery, and museum. But the rapidly rising costs of city life since the 1980s has had other, more practical consequences for artists, especially those grappling with the fraught financial conditions that tend to go with the beginning of a career. The Jeff Koonses of the world aside, how do artists afford a functional studio in a place like New York or London, where rent checks siphon off most of your income?

Then again, do you even need a studio at all? As web-based media, mobile interventions, and 3D printing proliferate in the art world, an artist working today with a phone or laptop might find the studio an antiquated notion altogether.

—George Philip LeBourdais

For these artists, the post-studio practice was as much a political stance as an aesthetic one, an attempt to dissolve the constrictive joints between studio, gallery, and museum. But the rapidly rising costs of city life since the 1980s has had other, more practical consequences for artists, especially those grappling with the fraught financial conditions that tend to go with the beginning of a career. The Jeff Koonses of the world aside, how do artists afford a functional studio in a place like New York or London, where rent checks siphon off most of your income?

Then again, do you even need a studio at all? As web-based media, mobile interventions, and 3D printing proliferate in the art world, an artist working today with a phone or laptop might find the studio an antiquated notion altogether.

—George Philip LeBourdais

No comments:

Post a Comment