A Brief History of Women in Video Art

- Turbulent, 1998

In the 1960s, following the post-war advent of television in America, video cameras became available to consumers and quickly found their way into the hands of the international art scene. Lauded as the grandfather of video art, Nam June Paik was one of the very first to employ the technology, in 1963, with his Galerie Parnass show “Exposition of Music: Electronic Television”—and was soon followed by a slew of innovators like Vito Acconci and Peter Campus, who experimented with video in the early ’70s.

Unlike traditional mediums, however, this one wasn’t dominated by men. In video, women found a form free from the male-dominated canon, in much the same way that performance art provided unchartered territory for experimentation. Pioneering women like Valie Export and Joan Jonas quickly adopted the new technology, and today they are celebrated for their trailblazing legacy that paved the way for tenacious artists like Diana Thater, Shirin Neshat, and Sarah Morris. Now, a new generation of female artists including Rachel Rose, Chloe Wise, and Kate Cooper is building upon this rich history with bravado. Here, we take a look at how and why women became leading innovators of the digital medium.

Unlike traditional mediums, however, this one wasn’t dominated by men. In video, women found a form free from the male-dominated canon, in much the same way that performance art provided unchartered territory for experimentation. Pioneering women like Valie Export and Joan Jonas quickly adopted the new technology, and today they are celebrated for their trailblazing legacy that paved the way for tenacious artists like Diana Thater, Shirin Neshat, and Sarah Morris. Now, a new generation of female artists including Rachel Rose, Chloe Wise, and Kate Cooper is building upon this rich history with bravado. Here, we take a look at how and why women became leading innovators of the digital medium.

- Still from Touch Cinema, 1968

- Vertical Roll, 1972

Female performance artists of the 1960s and ’70s—including Hannah Wilke and Martha Rosler—were some of the first to adapt to video, using the medium to record and preserve their work. The relative portability of the aptly named Portapak (pioneered by Sony and used by many early video artists) made it easy to use for documentation and experimentation.

Austrian artist Valie Export grabbed headlines with works, like Splitscreen-Solipsismus (1968)—an 8mm film depicting a boxer fighting against himself—that wittily played with the medium’s formal qualities. Arguably Export’s most groundbreaking piece was Facing a Family (1971), which aired on Austrian television and showed a nuclear family watching TV and eating dinner. Through this mirror image of the TV-watching public, she disturbed the relationship between content consumer and creator in a way that pushed boundaries left unexplored by even most avant-garde cinema.

But it was Joan Jonas’s Vertical Roll (1972), in which she jarringly interrupted the video’s electronic signal while she performed in front of it, that really moved the dial, blending mediums and technologies. A fitting contemporary foil to Jonas’s Vertical Roll can be found at the New Museum, where artist Wynne Greenwood’s show “Kelly” focuses on her complete archive of performances as members of her “female band,” Tracy and the Plastics. Greenwood created the series by performing in front of a video projection, effectively allowing her to simultaneously perform as all three of the band’s members.

Austrian artist Valie Export grabbed headlines with works, like Splitscreen-Solipsismus (1968)—an 8mm film depicting a boxer fighting against himself—that wittily played with the medium’s formal qualities. Arguably Export’s most groundbreaking piece was Facing a Family (1971), which aired on Austrian television and showed a nuclear family watching TV and eating dinner. Through this mirror image of the TV-watching public, she disturbed the relationship between content consumer and creator in a way that pushed boundaries left unexplored by even most avant-garde cinema.

But it was Joan Jonas’s Vertical Roll (1972), in which she jarringly interrupted the video’s electronic signal while she performed in front of it, that really moved the dial, blending mediums and technologies. A fitting contemporary foil to Jonas’s Vertical Roll can be found at the New Museum, where artist Wynne Greenwood’s show “Kelly” focuses on her complete archive of performances as members of her “female band,” Tracy and the Plastics. Greenwood created the series by performing in front of a video projection, effectively allowing her to simultaneously perform as all three of the band’s members.

As Conceptual, Feminist, and Body Art movements developed during the 1970s, video represented a powerful new opportunity to resolve and represent the complex issues that were being surfaced by those crossover genres. Building on Andy Warhol’s earlier “Screen Tests,” starring green-lit personalities like Edie Sedgwick and Lou Reed, artists like Dara Birnbaum toyed with cinematic conventions on their own terms—which in her case meant mining the comic book Wonder Woman.

In her epic Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978-1979), Birnbaum appropriated imagery from the television show adaptation to reflect on the cultural discourse embedded in the feminine superhero. Video also allowed feminist artists like Export and Birnbaum to reach wider audiences (both artists have had their works appear on television channels).

In her epic Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978-1979), Birnbaum appropriated imagery from the television show adaptation to reflect on the cultural discourse embedded in the feminine superhero. Video also allowed feminist artists like Export and Birnbaum to reach wider audiences (both artists have had their works appear on television channels).

- Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet's Garden, Part 1, 1992

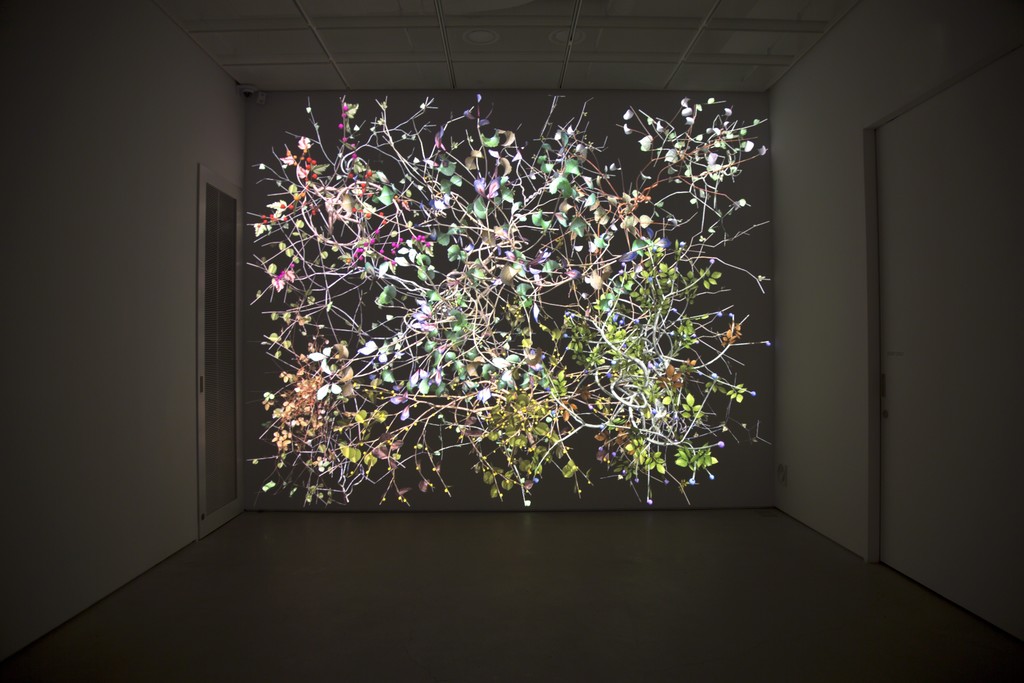

- Diaspore5, 2014

As the sophistication of video technology increased, so did artists’ familiarity with it—and they soon took to the edit button, distorting and manipulating footage, as well as lacing it together with other forms of art. Doris Totten Chase, who received early support from Nam June Paik in the 1970s and ’80s, began using computers to add effects to her light-filled dance performances. Her early riffs on these then-cutting-edge techniques paved the way for artists like Meriem Bennani, who inserted analogue animations into her online videos. Jennifer Steinkamp also experimented with animation in the 1980s, and her bursting trees and digitally fabricated florals have been shown around the world.

In the ’90s, Diana Thater—who currently has a retrospective at LACMA—stood out from the crowd with landmarks like OO FiFi, Five Days in Claude Monet’s Garden, Part 1 and Part 2 (1992), which she shot at the estate of the late artist before deconstructing the footage into video’s red, green, and blue (RGB) components. And Surrealist video artists Pipilotti Rist and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster garnered attention thanks to ambitious projects transforming everyday happenings into masterpieces.

Pickelporno (1992), in which a surveillance camera sweeps over a fornicating couple, won Rist notoriety as well as accolades for its strange take on the sensual. Gonzalez-Foerster’s installations collaged video together with architecture and design to create unique and immersive environments. And Sarah Morris combined the graphic painter’s eye for patterns with the perspective of the documentarian in the early 2000s with films like AM/PM (1999), Capital (2000), and Miami (2002).

Pickelporno (1992), in which a surveillance camera sweeps over a fornicating couple, won Rist notoriety as well as accolades for its strange take on the sensual. Gonzalez-Foerster’s installations collaged video together with architecture and design to create unique and immersive environments. And Sarah Morris combined the graphic painter’s eye for patterns with the perspective of the documentarian in the early 2000s with films like AM/PM (1999), Capital (2000), and Miami (2002).

In the late ’90s and early 2000s, Sharon Lockhart and Shirin Neshat continued in this documentary-style vein with eyes on different parts of the world. For Lockhart, far-flung locations like Japan’s Goshogaoka neighborhood interested her as much as the bucolic life of children in the Sierra Nevada Mountains that she captured in Pine Flat (2005). Neshat’s politically inclined films like Turbulent (1998) and Rapture (1999) intimately examined issues of gender and power in the Muslim world. And partners and sisters Jane and Louise Wilson similarly probed the narratives latent in our social and political environments with works like Gamma (1999), a Turner-Prize-nominated piece filmed at an abandoned U.S. military base.

- Grosse Fatigue, 2013

As in the 1960s, women video artists continue to chase new avenues of expression and embrace an increasingly complex world both online and off—with innovators like Camille Henrot and Hito Steyerl leading the pack.

—Kat Herriman

Cover image: Joan Jonas, Double Lunar Dogs, 1984. Image courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix.

—Kat Herriman

Cover image: Joan Jonas, Double Lunar Dogs, 1984. Image courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix.

No comments:

Post a Comment