|

|

The museum of the future: how architects are redefining cultural landmarks

What does the museum of the future look like? As art evolves, so do the spaces that house it – pushing architects to rethink form and function

It could be said that an art museum is the ultimate project for an architect: they’re high-profile, often come with a handsome budget, are open to the public, and allow for creativity at its greatest expression. A handful of top architecture firms, including Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Frank Gehry, and Herzog & de Meuron, have made cultural institutions and museum projects a cornerstone of their practices, and for good reason.

They’re temples dedicated to creative freedom and radical expression, among other ideas, and are increasingly serving as community gathering spaces. Following the decline of the mall and the rise of technology that has moved so much of life online, one could argue that they’re perhaps the last great public space. But as attendance records swell and audiences change, and art continues to evolve beyond what can fit in a frame or on a plinth, so must the museums that house it, requiring architects to rethink what the contemporary museum and its surroundings look and feel like.

Centre Pompidou

The museum of the future: what is it?

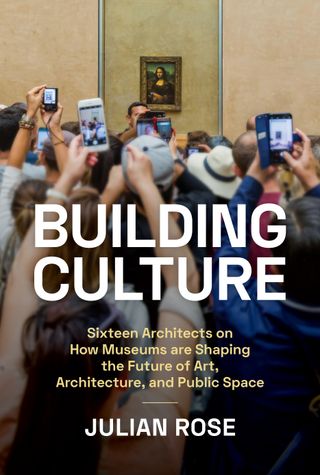

'As contemporary art has evolved beyond modern art, it has become much more compatible with the space of the museum,' explains art and architecture historian Julian Rose, the author of Building Culture (Princeton Architectural Press, 2024), which features 16 conversations with leading architects about the role museums play in shaping the future of art, architecture, and public space. Whereas much of 20th-century art was to be viewed in the homes belonging to private collectors or in white cubes, contemporary artists are expanding their practices to include more film-, performance-, digital-, and immersive-based pieces. This is more collective in its experience and intended specifically for larger audiences than a single viewer.

And so, throngs of leading museums across the globe recently have been or currently are in the process of re-examining what their institutions should look and feel like by enlisting the expertise of the world’s leading architects to usher them into the future. Think: MoMA’s 2019, $450 million renovation and expansion by Diller Scofidio + Renfro with help from Gensler, which created 40,000 sq ft of more gallery space, like the Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Studio that’s dedicated to performance and sound exhibitions.

There is the forthcoming Centre Pompidou’s $280 million multi-year closure from 2025 to 2030 to add over 200,000 sq ft of new exhibition space to accommodate contemporary and multidisciplinary creations that will invite diverse audiences in, building upon Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ intent to foster a social utopia; or, take landscape architect Walter Hood, whose thoughtful and layered open spaces around the International African American Museum in Charleston allow for reflection and gathering.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art reimagined galleries dedicated to the Arts of Africa, the Ancient Americas, and Oceania, by Kulapat Yantrasast of WHY Architecture

This spring alone will see the re-opening of a slew of projects following ambitious renovations, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Michael C Rockefeller Wing for the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas designed by Kulapat Yantrasast, as well as Annabelle Selldorf’s visionary redesign of New York’s Frick Collection and her reconfiguration of the entrance to the National Gallery’s Sainsbury Wing in London.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art reimagined galleries dedicated to the Arts of Africa, the Ancient Americas, and Oceania, by Kulapat Yantrasast of WHY Architecture

The draw of the museum for an architect is that such a commission plays to their strengths; it’s a balance of light, scale, movement and materials that allows for artistic expression and making a statement, but it’s also, at its core, building a structure for the community. 'What I do is always fuelled by thinking about the visitor, thinking about how someone would perceive the space, how they would move around in it… In many ways, of course, it is about making the spaces for the art, but in an equal manner also making the trip to the museum something that is much more agreeable,' says Selldorf. The experiential aspect of architecture has always been a guiding principle for architects, and in the 21st century, more are taking note to be thoughtful in considering what the visitor requires and how museums can respond to it.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The Frick Collection, New York, by Selldorf Architects

The cover of Rose’s book features Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, perhaps the world’s most recognisable work of art, surrounded by a battery of cellphone-wielding visitors, eyeing the work through their screens. The experience of viewing the work in person amidst record-breaking crowds has become so tension-wrought that the Louvre has recently announced its decision to move the work to its own dedicated gallery.

Selldorf Architects' plans for the National Gallery's Sainsbury Wing, London

The relocation serves to set an important precedent for museums facing similar problems with their star pieces, but Rose is optimistic about the future of museums and the solutions architects can provide. 'If you’ve ever gone to a museum to try and see an artwork as famous as the Mona Lisa in person, you know that many of these tensions are still unresolved, and architects will have to continue to think creatively about how to respond to new technologies and to the shift they cause in our culture.'

Katherine McGrath is a writer, editor, and creative consultant based in Paris. She has spent over a decade covering art, culture, architecture, travel, luxury, and design, as well as food, film, and fashion on occasion. Her work has appeared in T: The New York Times Style Magazine, Vogue, Condé Nast Traveler, Cultured, L’Officiel, Artsy, and Creative Nonfiction, among other publications. She previously held editorial roles at Architectural Digest and Assouline, where she oversaw the editing and development of both in-house and client titles. She lives by the Bastille with her boyfriend and their dog.

No comments:

Post a Comment