previously (2018) about the same manuscript

2 articles

...|...

Art World

Did Artificial Intelligence Really Decode the Voynich Manuscript? Some Leading Scholars Doubt It

Scholars questioned the methodology of the paper that sparked the reports.

Last month, some remarkable news surfaced: the fabled Voynich manuscript had finally been decoded by artificial intelligence. But it turns out that the content of the cryptic 600-year-old, 240-page document—written in a language nobody has ever seen before or since—may still be a mystery.

Scholars and Voynich experts quickly sought to set the record straight, expressing doubts over the accuracy of the research methodology applied in the 2016 paper that claimed to have cracked the ancient puzzle.

Most scholars agree that the manuscript is written in a substation cipher, a simple code in which certain letters of the alphabet are interspersed with made-up ones. The problem that has confounded researchers for centuries is that nobody knows what language (or alphabet) the document was originally written in.

In Decoding Anagrammed Texts Written in an Unknown Language and Script, written by computer science professor Grzegorz Kondrak and graduate student Bradley Hauer of the University of Alberta in Canada, the researchers developed a methodology for finding the source language of ciphered texts and then tested the algorithm they developed on the ancient manuscript. In the end, Kondrak and Hauer concluded that the Voynich was originally written in Hebrew. But scholars are questioning the methodology they used to arrive at this conclusion.

Kondrak and Hauer wrote an algorithm to identify certain patterns in texts such as how often each letter or combination of letters appears. Next they used the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (which is translated into 380 languages) as a sample text to teach the algorithm to identify the original language of a text encrypted with substitution ciphers—which worked—but when they turned the algorithm on the Voynich manuscript, problems began to emerge with some of their underlying assumptions.

Lisa Fagin Davis, executive director of the Medieval Academy of America, told the Verge that an algorithm trained to identify modern languages cannot reliably be used to identify the language of a document that has been carbon dated to the 15th century. “The grammar, spelling, and vocabulary would have been quite different, especially for a manuscript like the Voynich that is scientific in nature,” Davis said.

In addition, Kondrak and Hauer’s algorithm merely produces suggestions for potential matches but doesn’t evaluate the likelihood of these matches. Beyond that, the researchers based their analysis on a debatable theory that the Voynich is also encoded in anagrams, a hypothesis that has been suggested before but which is not supported by scholarly consensus.

Kondrak and Hauer admit in the paper that they had to make some adjustments for the translation to make sense in Hebrew, writing that the first attempt was “not quite coherent.” The adjustments included making “a couple of spelling corrections” before using Google Translate to convert the text into English. “Any time you have to resort to Google Translate over someone who has actually studied the language, you’re going to lose some credibility,” Fagin said.

Speaking to the Verge, professor Shlomo Argamon, a computational linguist at the Illinois Institute of Technology, concluded that “their method… gives them huge latitude in doing this sort of impressionistic interpretation. They take this decoded sentence, squint at it through thick eyeglasses, and say that’s good enough for us.” Nick Pelling, a Voynich expert who’s written several books on the mysterious document goes even further, saying that the paper’s likelihood of being correct is “So close to zero percent as makes no practical difference.”

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

Art World

AI May Have Just Decoded a Mystical 600-Year-Old Manuscript That Baffled Humans for Decades

The secret to the Voynich Manuscript? It's in a language no one expected.

One of the world’s most infamous mysteries may have just been solved, thanks not to human genius, but to artificial intelligence. Named after Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish book dealer who purchased it in 1912, the 240-page Voynich manuscript is written in an unknown script and an unknown language that no one has been able to interpret—until now.

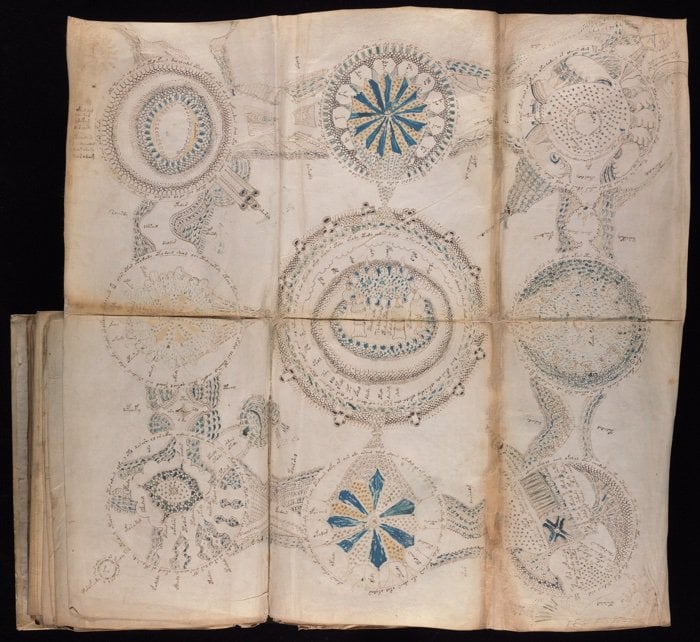

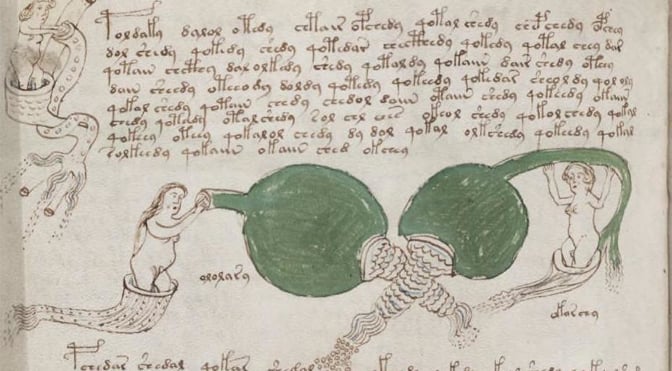

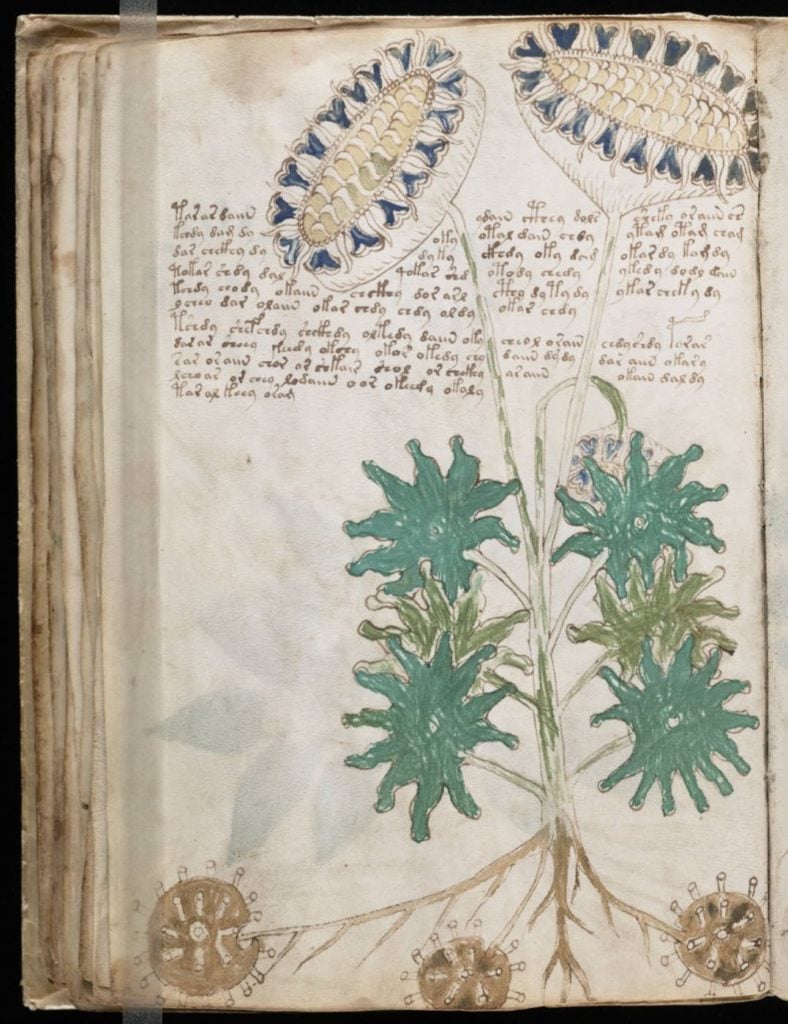

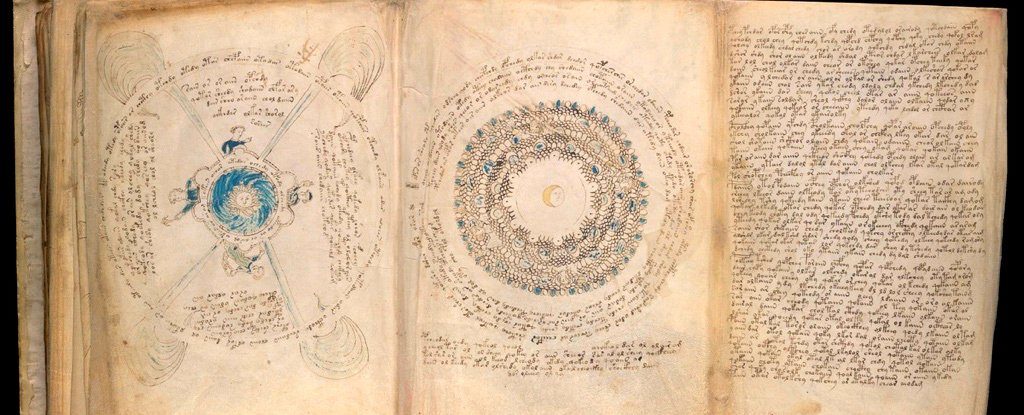

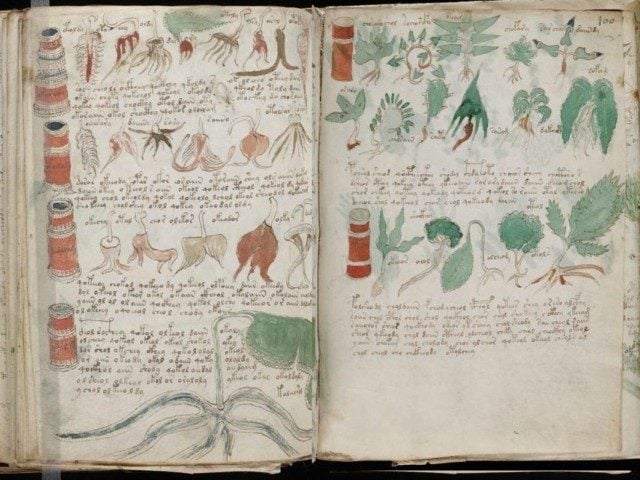

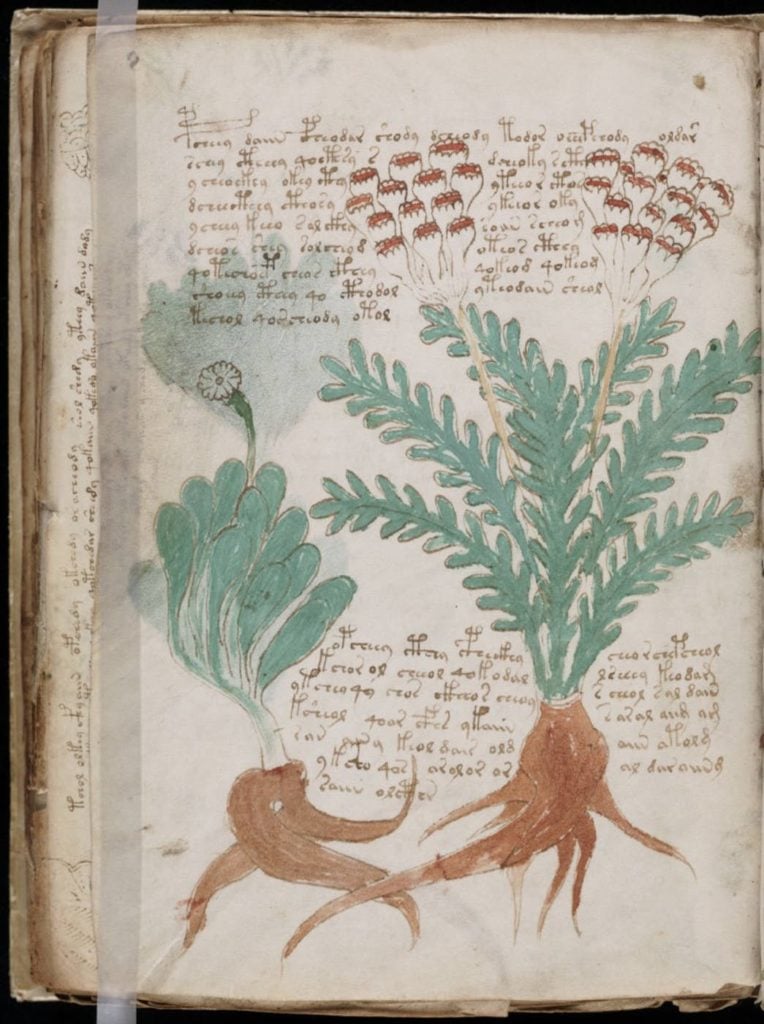

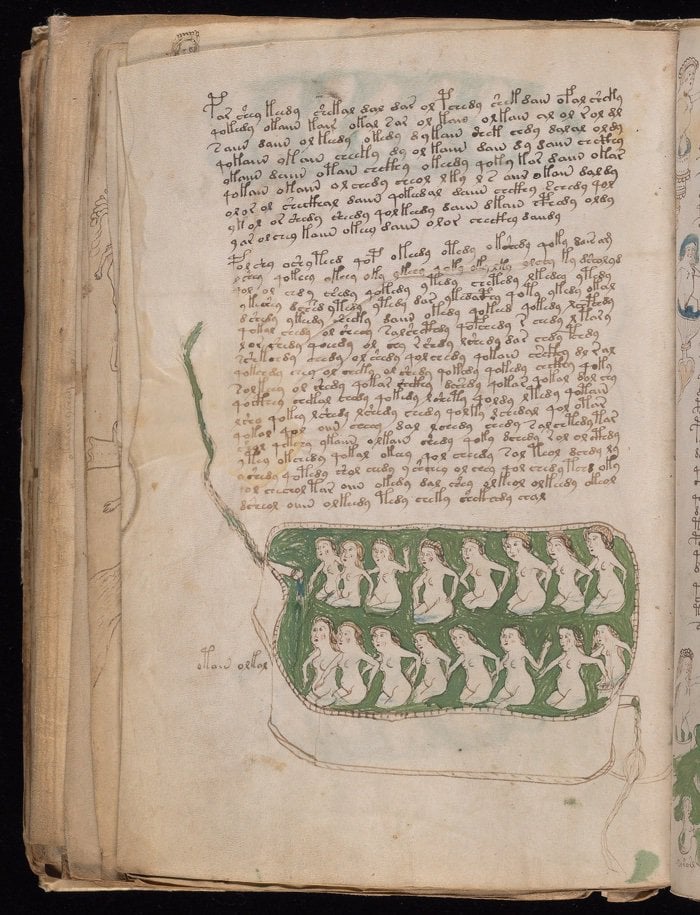

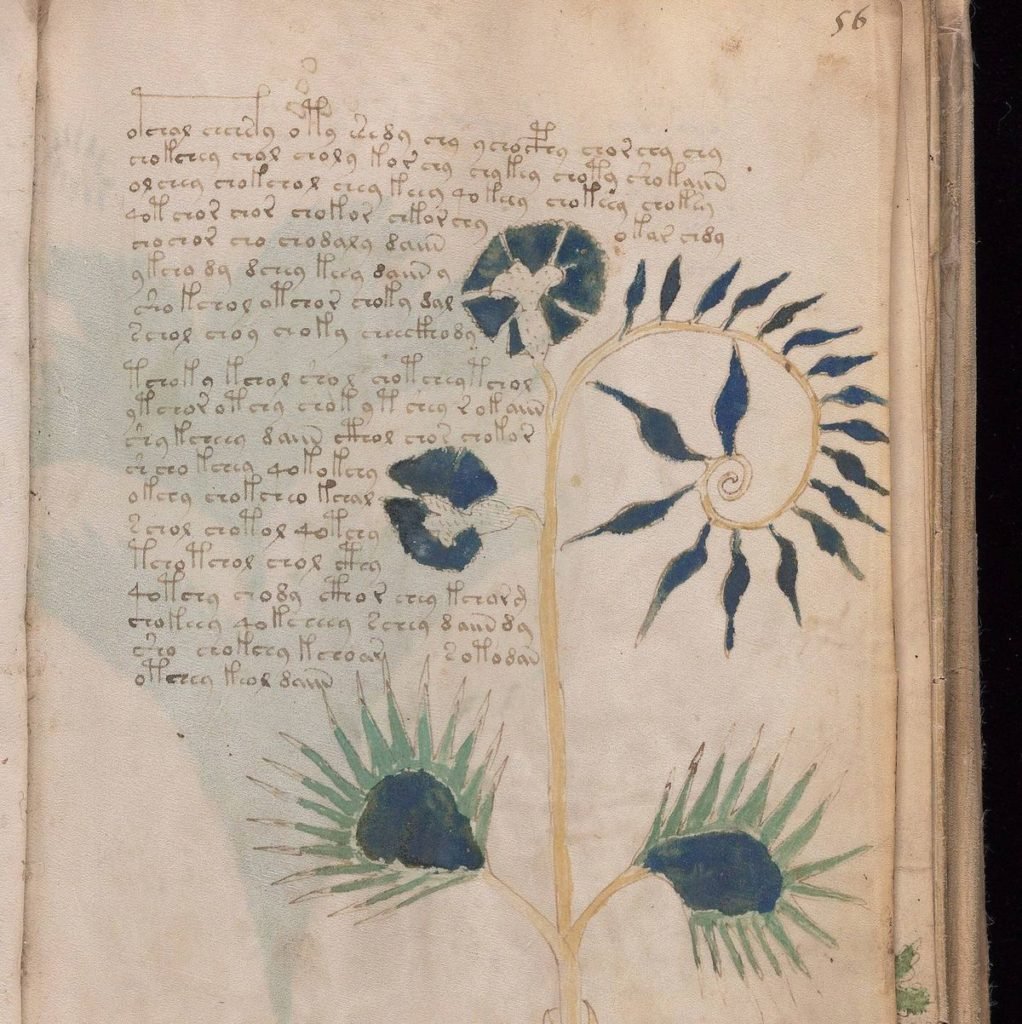

Computing scientists at the University of Alberta claim to have cracked the code to the inscrutable handwritten 15th-century codex, which has baffled cryptologists, historians, and linguists for decades. Stymied by the seemingly unbreakable code, some have speculated it was written by aliens. Experts have even posited that the whole thing is a hoax with no hidden meaning. Today, housed at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in New Haven, Connecticut, the manuscript’s delicate vellum pages are illustrated with botanical drawings, astronomical diagrams, and naked female figures.

When it came to tackling the centuries-old mystery, professor Greg Kondrak and grad student Bradley Hauer put their expertise in natural language processing to good use, running algorithms that compared the document’s text to the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” in no less than 380 different languages. According to the computer, the Voynich manuscript was written in Hebrew.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Canadian computing scientists believe they are cracking the code with the help of artificial intelligence. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Other researchers had previously hypothesized that the document had been encoded using alphagrams, the letters in each word rearranged in alphabetical order. Based on that theory, Kondrak and Hauer used an algorithm to solve each anagram in the first 10 pages.

“It turned out that over 80 percent of the words were in a Hebrew dictionary, but we didn’t know if they made sense together,” Kondrak told the university. (He published his findings in the journal Transactions of the Association of Computational Linguistics.)

Their colleague, Hebrew-speaking computer scientist Moshe Koppel, took a crack at reading the first line to no avail. But, aided by a couple of spelling corrections, Google Translate had better luck.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Canadian computing scientists believe they are cracking the code with the help of artificial intelligence. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

If the Alberta team is right, the first sentence of the manuscript reads “she made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people.” Weird, yes, but an impressive breakthrough nonetheless.

Of course, after all these years, the Voynich Manuscript isn’t giving up all its secrets at once. Last year, scholars quickly debunked the claims of Nicholas Gibbs, who announced he had translated the tome from an abbreviated version of Latin and that it was a women’s health manual.

In their paper, Kondrak and Hauer acknowledged that more work needs to be done to definitively prove the accuracy of their discovery, but called their findings “a starting point for scholars that are well-versed in the given language and historical period.” Hopefully, Hebrew experts will follow up on this groundbreaking research and solve this mystery once and for all.

See more pages from the Voynich Manuscript below.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Canadian computing scientists believe they are cracking the code with the help of artificial intelligence. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Canadian computing scientists believe they are cracking the code with the help of artificial intelligence. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Canadian computing scientists believe they are cracking the code with the help of artificial intelligence. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Canadian computing scientists believe they are cracking the code with the help of artificial intelligence. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Canadian computing scientists believe they are cracking the code with the help of artificial intelligence. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Canadian computing scientists believe they are cracking the code with the help of artificial intelligence. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Canadian computing scientists believe they are cracking the code with the help of artificial intelligence. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Canadian computing scientists believe they are cracking the code with the help of artificial intelligence. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

Article topics

No comments:

Post a Comment