Analysis

The Gray Market: Why Art Gallery Attendance Is the Wrong Metric to Measure (and Other Insights)

Our columnist on lessons from the Chelsea Art Walk, a subsidized House for Artists, and the complications of New York's Culture Pass.

Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, stories about multiple scarcities in the arts—and their effects on both the for-profit and nonprofit sides of the industry…

Chelsea’s Gallery District. Photo via Flickr.

WALK THIS WAY

On Wednesday, my colleague Rachel Corbett used the first-ever Chelsea Art Walk, an evening gallery crawl in New York’s most lux and concentrated for-profit art district, to examine dealers’ “vintage approaches” to the near-extinction of foot traffic in permanent commercial exhibition spaces around the world.

But with all due respect to the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA), who organized the event, and the member galleries who participated in it, my concern isn’t so much that they’re looking to the past for answers. It’s that they may not be interrogating history hard enough, or doing as much as they need to with the results of the inquiry, to actually solve the problem long term.

In fairness, I’m encouraged that even the Chelsea Art Walk’s originator sees the event as more of an opening act than a resolution. Corbett quotes Julie Saul, the Chelsea gallerist who proposed the idea to ADAA leadership six weeks ago, saying, “I don’t think this art walk is going to change anything that significantly.”

Still, I’d wager even that note of caution qualifies as an understatement. To me, expecting one gallery walk to re-ignite in-person viewership in the digital era would be like expecting one screening of Gone with the Wind to convince legions of teenagers to permanently abandon their favorite YouTubers and binge on Golden Age cinema instead.

Maybe it’s not a bad first step, but it does beg the question of what comes next.

Although I understand the impulse to simply get people back into galleries, I also strongly believe that gallerists, particularly those of the midlevel and emerging variety, would do much better to focus on engagement rather than sheer attendance. In other words, the goal should be to try to actively draw and meaningfully connect with potential viewers over and over, not just convince them to pop in and glance around occasionally.

Based on what I heard and read, the Chelsea Art Walk showcased both sides of the issue. While some galleries staged special programming, such as performances and artist talks, other were only nominally active. The latter group was open to visitors, but nearly devoid of staff (particularly the gallerists themselves), and they apparently offered little else to help introduce anyone to, or transfix anyone with, the works on view.

I’d love it if we lived in a world where significant numbers of people could waltz into a gallery once and be pierced by Cupid’s arrow, so that they instantly fall in love with contemporary art for the rest of their lives. But I also wish we lived in a world where major news organizations were rigorous enough about facts not to blindly parrot a fourth grader’s admirable but wildly flawed estimate that humanity uses 500 million plastic straws a day.

Sadly, the world we live in is neither of these.

Which is why I think galleries’ best chance for building (or rebuilding) sustainable audiences now revolves around developing robust, long-term, event-based programming on top of their exhibition cycles.

I covered this in much greater depth in my book, but the upshot is that both historical and recent evidence suggests that live, socially based experiences may be the most viable way to activate people’s interests in the arts, even in a digital age.

Remember, the original Parisian salons were as much see-and-be-seen social clubs as they were intellectual investigations. Fast forward to the 21st century, and IRL events are still drawing major crowds. In 2016, auditing giant PricewaterhouseCoopers estimated that ticket sales to live shows made up 43 percent of the US music industry—about 2.5 times all revenue from Spotify and other streaming outlets.

I’d also argue that gallery longevity has most often been built on establishing communities of engagement. Examples span a wide range of time periods and business sizes, from powerhouse Lisson Gallery’s start in the 1960s, to Night Gallery’s growth in Los Angeles in the 2000s, to Postmasters Gallery’s ability to hold steady in the mid-market since the 1980s (most recently with a crowdfunding campaign whose rewards eschew collectible objects). All of these galleries (and more) succeeded as much by becoming community hubs for kindred spirits as by showing interesting art.

In that sense, the healthy attendance at the ADAA’s first Chelsea Art Walk offers additional support to the idea that art events can still be magnetic in the social media era. The danger would be to fool ourselves into believing that intermittent programming and passive participation can be enough for galleries to regain traction. Here’s hoping more gallerists take the right lessons from history—and accept the challenge of activating their spaces with more events (and more frequent ones) than just exhibition openings.

The artist Grayson Perry in 2015. Photo Stuart C. Wilson/Getty Images.

A HOUSE DIVIDED

On Tuesday, Jess Denham of Homes & Property reported that former Turner Prize recipient Grayson Perry will lead a judging panel to award 12 British artists subsidized flats in a new development in Barking, East London. In exchange for “promot[ing] arts through arts groups, film screenings, and local meetings held in the building’s new community art center,” the winners will pay only 65 percent of the market rate for their two-bedroom apartments. Denham says that the building, appropriately dubbed A House for Artists, should be ready for its new residents to move in by November 2019.

On one hand, I think it’s great that 12 artists will be rewarded for their labor with brand new, reduced-rate housing in a global arts hub. With the possible exceptions of starry-eyed utopian dreamers and people who have just recently taken mind-altering drugs, everyone reading this recognizes that it’s relatively rare for artists to be able to sell enough work to cover 35 percent of the rent for a two-bedroom apartment in London.

A House for Artists at least reopens the door to an alternative art economy, in which artists can earn meaningful compensation without making and selling works in a harsh capitalist system dominated by big galleries and big names. That’s not nothing, especially if it’s a first step to many more significant ways to rethink the value of art and its makers.

At the same time, I think that celebrating any setup like this without some serious qualifiers would shoot so wide of the actual target that it could shatter windows in the nearest parking lot. In my eyes, A House for Artists is not unlike those “feel-good” stories where some unfortunate American without health insurance manages to crowdfund their own cancer treatment, or where caring co-workers give their unspent vacation days to expecting American mothers whose employers have no legal obligation to award them paid maternity leave.

Perry isn’t wrong when he calls A House for Artists “a golden opportunity.” I just think that the development is also an emblem of how a supposedly advanced society has transformed basic human rights like affordable housing into a scarce reward only bestowed upon a chosen few in a perversely meritocratic system—more Hunger Games than game changer.

To be clear, the UK is not the only leading art market both to resort to this concept and to get some good press out of it. Broadly similar subsidized housing projects for artists are either in development or already active in American metropolises like New York, San Francisco, and even Nashville. Which wouldn’t seem so dubious to me if the scarcity of affordable housing for anyone, period, wasn’t announcing itself as perhaps the next great global crisis.

If you’d like some examples, they range from the macro to the micro. A recent report estimated that, from 2000 to 2015 alone, “the US produced 7.3 million fewer homes than it needed to [in order] to keep up with demand and population growth.” In Los Angeles, the American art industry’s west coast capital, homelessness rose by 75 percent in the past six years. And as of this April, the median house price in San Francisco hit an unconscionable $1.6 million.

Again, I’m not trying to lash out at Perry or the rest of the organization behind A House for Artists. But before we congratulate them for gracing a few lucky artists with desirable real estate in exchange for non-market labor, we should consider what the program’s shining exceptionalism says about our baseline expectations for anyone living in a civilized society today, not just artists alone.

And from that perspective, maybe the best way to help artists would be to expand our lens far beyond a narrow focus on art world needs.

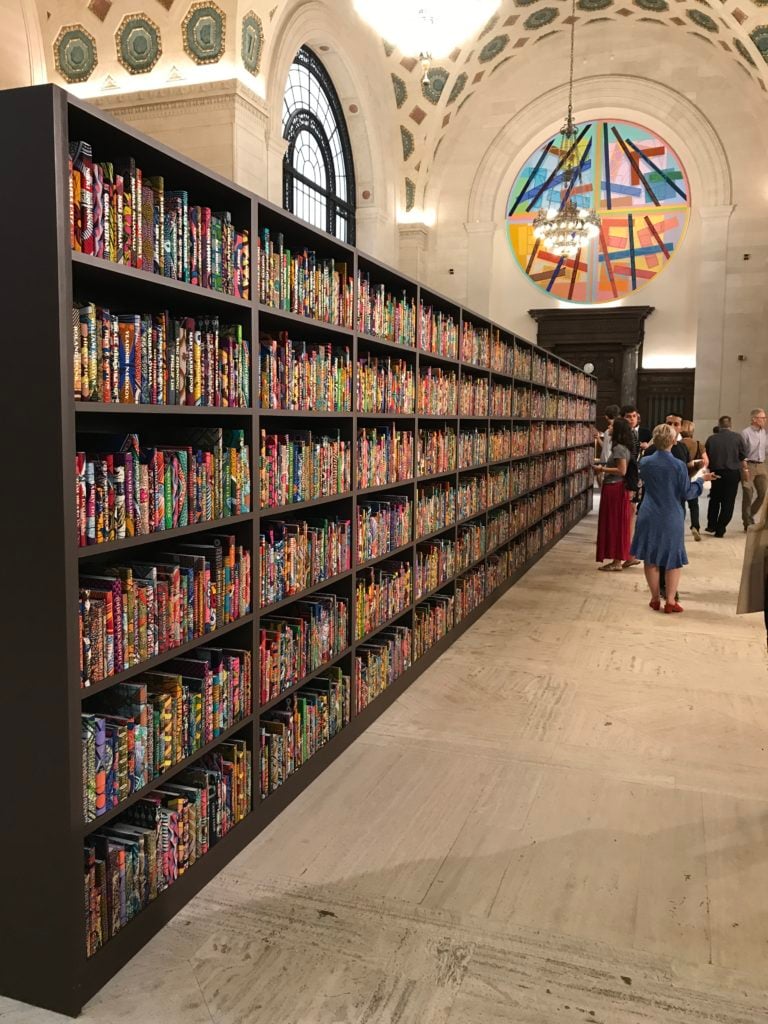

Yinka Shonibare MBE, The American Library, 2018. Photo by Tim Schneider.

JUST PASSING THROUGH

Finally this week, my colleague Sarah Cascone added a sobering update to a story that many people met with jubilation only a few days earlier. Monday saw the announcement of Culture Pass, a new initiative in which anyone with a New York Public Library, Brooklyn Public Library, or Queens Library card would be able to secure a set of up to four tickets annually from 33 museums and cultural institutions in the five boroughs.

In a year when the art world has gotten more aggravated by museum admission prices than old socialists by Kardashian scion Kylie Jenner’s alleged $900 million net worth, Culture Pass sounded like a huge win for New Yorkers, particularly since participating organizations could allocate blocks of tickets specifically for residents of underserved neighborhoods.

But one important detail of the program appears not to have been unpacked clearly enough in the triumphant press release: namely, that only a limited number of Culture Passes would be available from each museum in any given month. And in tandem with that detail, few people probably expected there to be as much truth as there is to Queens Library President Dennis M. Walcott’s declaration that “Culture Pass is going to be one of the hottest tickets in town for New York City’s public library cardholders.”

According to a spokesperson, 9,500 of October’s roughly 14,500 Culture Passes had already been reserved by last Friday. As of publication time, this initial surge of demand takes 10 of the 33 participating institutions—including the Met, MoMA, the Whitney, and the Frick—off the table completely for the initiative’s opening month. (The spokesperson says that organizers are in conversation about adding more passes to the monthly pool.)

Now, I’m generally in favor of anything that opens up access to cultural institutions for more people, especially in communities that have often been left behind. But Culture Pass’s limitations, which only took four days to emerge in blazing neon lights, also demonstrate an important wrinkle in the museum admission debate.

Outside of specially ticketed exhibitions, most people (understandably) tend to think of museums as what economists call a non-rival good. This means that my ability to access them has no effect on anyone else’s ability to do the same simultaneously.

Sure, the galleries can be more or less crowded. But how many times in your life have you been turned away from the general admission counter because the museum is at capacity? Probably fewer times than you and your neighbors have had to ration running water (another non-rival good in developed countries).

Yet this is a misconception of how museums work. Even if you want to ignore the attendance limits set by fire code, museums can only serve a certain amount of people at a certain time. Otherwise, the galleries would overflow with frustrated patrons, security would be overwhelmed, art would get knocked around like it had been installed on a rugby field, and pandemonium would ensue.

Nor can museums stay open 24/7 to meet the demand. Staffing, utilities, maintenance—you need all of these to present exhibitions to the public, and each comes at a price. As I wrote earlier this year, there’s no such thing as a free museum. It’s just a matter of who’s paying the costs—and why.

Culture Pass reinforces this idea. Why are the tickets free for New York library cardholders? Because the entry fees are being paid by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, the Charles H. Revson Foundation, and the New York Community Trust’s Thriving Communities program.

This fact highlights that there are really only two ways to generate more Culture Passes in a given month: Get those same foundations to contribute even more cash, or source more funding from other philanthropists. Otherwise, we’d be asking the museums themselves to sacrifice their own operating revenue to create more “free” tickets. And given how many of them are already struggling financially, I don’t think that’s really a viable plan.

In short, I understand why people who were overjoyed about Culture Pass last Monday might feel hoodwinked a week later. But I also understand why the unglamorous realities of running museums make Culture Pass more complicated than most people (including me) would like. It’s not a perfect program, obviously. Let’s just not make the mistake of turning the perfect into the enemy of the good, however modest it may be.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, here’s hoping that, in another seven days, our problems are all a little scarcer than today.

Follow artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

SHARE

No comments:

Post a Comment