The Shanghai Art Factory That’s Constructing Massive Public Artworks

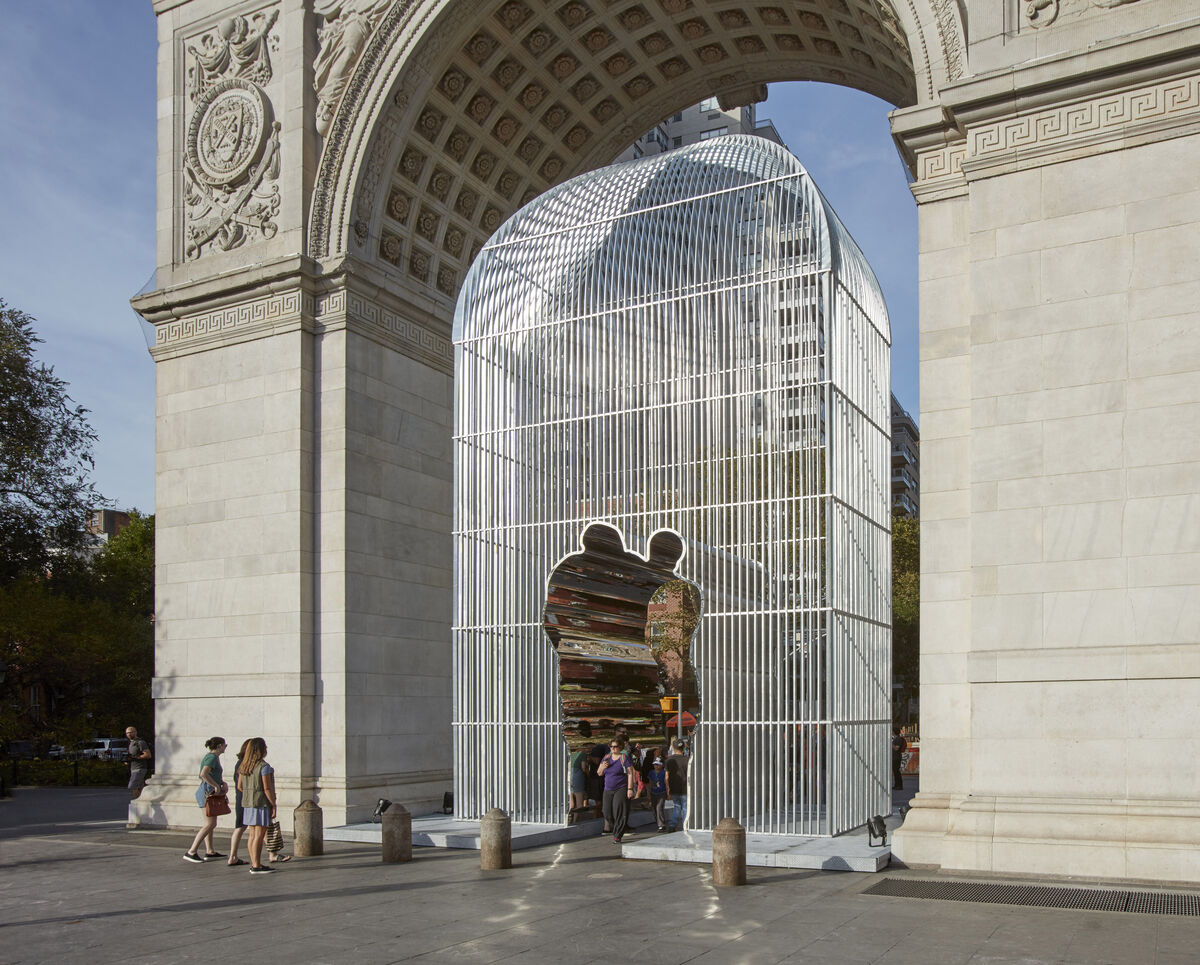

Ai Weiwei, Arch, 2017, New York. On view as part of the citywide exhibition“Good Fences Make Good Neighbors,” presented by Public Art Fund. Courtesy of UAP.

One of the jewels of Ai Weiwei’s “Good Fences Make Good Neighbors”—the sprawling Public Art Fund project the Chinese artist mounted across New York City last fall—was a gleaming steel cage that sat within the arch at Washington Square Park. The work quickly became a destination for droves of locals and tourists alike, but few likely knew that the work itself was made in a factory on the other side of the globe, in a suburb of Shanghai, China.

Ai’s piece was the first partnership between the New York-based nonprofit and the global design studio, Urban Art Projects (UAP). Specializing in commissioning, building, and installing large-scale public artworks, UAP now operates out of China, New York, and Australia.

The company’s wide swathe of international clients includes prominent artists, art galleries, architects, designers, art fairs, governments, and property developers. Past collaborators include Frank Gehry, Shop Architects, Sean Kelly Gallery, and Sullivan+Strumpf, plus artists like Leo Villareal, Sopheap Pich, and Richard Sweeney. To date, UAP’s 200-person-strong team has worked on projects in over 50 cities, with more than 2,600 collaborators.

Lawrence Argent’s Beyond Reflection being made at the UAP workshop in Shanghai. Courtesy of UAP.

UAP’s beginnings trace back to Australia in 1993, when brothers Daniel and Matthew Tobin were recent art school graduates living in Brisbane. They opened a 400-square-meter metal foundry in an outer suburb of the city, where they and fellow creatives could produce large works.

“I’d always been interested in public art,” Daniel told me with a laugh, recalling his undergraduate thesis show at the Queensland University of Technology. He had installed a figurative, fiberglass sculpture in a bathtub at a local mall. “It wasn’t amazing,” he admitted, but the project fulfilled his desire to bring art outside of white-cube galleries—an ambition that has become essential to all of the projects that UAP puts its name on.

Slowly, the Tobins built up a network of artists, curators, and architects, with whom they produced projects in the foundry, and helped foster a dialogue among these collaborators. In the original foundry, they cast their first public work, a piece by the Aboriginal artist Judy Watson. And while early site-specific installations like this one were heavily rooted in celebrating and visualizing Australian identity, UAP soon expanded its reach and repertoire. The Tobins moved their Brisbane operations to a 5,000-square-meter space, formerly used for train fabrication, where they continue to operate and have a foundry, paint shop, pattern shop, and metal shop.

Lindy Lee, The Life of Stars, 2015, Shanghai, China. Courtesy of UAP.

It wasn’t until 15 years into their practice, in 2009, that they opened a new factory in Asia. They chose to set up shop in China in hopes of breaking into what was then an untapped market—a growing upper class, expanding cities, and a rapidly developing property industry.

At the time, UAP had already established a global presence through works commissioned from the United States and the Middle East. For example, they worked with HOK Architects at King Abdullah University of Technology in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia, to install public works by Carsten Höller and Richard Deacon, among others; and they collaborated with artists Jeff Kopp, Chris Doyle, and David Trubridge on works for the Los Angeles mall Westfield Culver City. But working with Chinese clients had proved challenging.

UAP had run into logistical nightmares when it came to shipping works into China. Import taxes in the People’s Republic of China are known for being high (though this has fluctuated over the years), but other factors, too, made the endeavors extremely costly. The necessary paperwork must be reviewed meticulously in multiple languages, ensuring that all questions are answered correctly and meet bureaucratic standards. If any errors do occur, large works could easily get stuck in customs.

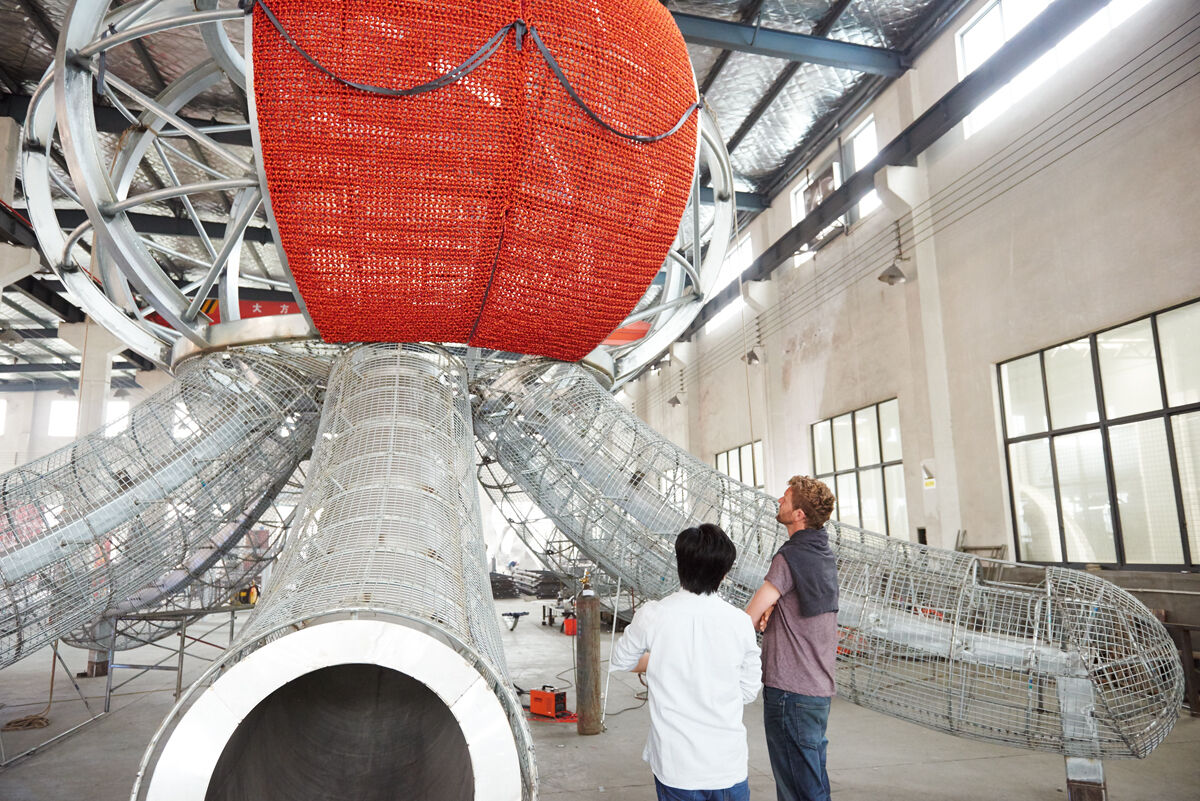

Florentijn Hofman visiting the UAP workshop in Shanghai, as his work, Kraken, was being made. Courtesy of UAP.

When working under deadlines, the Tobins explained, if a piece did get stuck, it would cost less to simply remake the work, and “file again under due process,” as it could take months to refile. In order to effectively work within the country’s borders, it became clear that artwork needed to be produced locally.

Since opening a workshop in China, UAP solidified design and construction contracts, established partnerships with artists, and has been able to ensure high-quality production that meets international standards. The Chinese workshop is of a similar scale to the Brisbane headquarters, and has facilities for pattern-making and metal fabrication. (UAP also has a mill-workshop in Long Island City, New York.)

Over the years, UAP has built up a global supply chain of fabricators who specialize in materials like hand-blown glass, ceramics, and stone. Additionally, the crew has been working with the Australian universities Queensland University of Technology and RMIT to incorporate innovative technologies into manufacturing, including robots that can build massive artworks.

Projects executed through the Shanghai factory evidence UAP’s versatility and deft ability to actualize a wide range of artworks.

Lawrence Argent, Beyond Reflection, 2017, in Shenzen, China. Courtesy of UAP.

In 2015, for example, Chinese-Australian artist Lindy Lee worked with UAP’s curatorial team to complete a six-meter-tall piece made from hand-beaten panel and mirror-polished stainless steel for Taiwanese property developer Ting Hsin. The resulting piece is a gleaming silver oval, titled The Life of Stars, which glows, thanks to an internal lighting system that sends luminous beams through perforations on the sculpture’s surface.

Another notable project, from 2016, was a collaboration with New York’s Sean Kelly Gallery to realize British artist Idris Khan’s 90-meter-long monument for Abu Dhabi’s Memorial Park, Wahat Al Karama. Comprised of 31 leaning panels, made from recycled aluminum sourced from decommissioned armored vehicles, the fabrication of the structure was split between the Australian and Chinese factories.

Recently, in 2017, UAP worked with Chinese master Song Dong to install neon, LED strip lights onto the heritage facade of Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum for his most recent retrospective, and later in the year, UAP’s design team helped Lawrence Argent create a 16-meter-tall, faceted dragon sculpture that sprawls over two levels of a sunken mall plaza in the southern city of Shenzhen, one of the fastest growing economic zones in the country. “Some of our most adventurous commissions are in China, in malls and the like,” Tobin explained.

Artwork by Idris Khan at the Wahat Al Karama memorial park in Abu Dhabi. Courtesy of UAP.

Another example of this is a massive interactive playscape by Dutch artist Florentijn Hofman (best known for his massive, floating rubber duck sculpture), which was commissioned for a waterfront park and mixed-use development also in Shenzhen. This site-specific piece, titled Kraken (2017), is inspired by its namesake, a mythological sea monster, but is decidedly less threatening, taking shape as a friendly, giant red octopus with a hat. A massive jungle gym made from colorful woven rope and metal armatures, it’s become a local landmark and photo-friendly destination, frequented by families with small children and school groups.

With a growing capacity and a respected practice, the Shanghai UAP studio has become ideal not just for local distribution, but for exports as well. Within the past few years, UAP has even been approached by major international art galleries seeking out potential manufacturing partnerships, hoping to create opportunities for their artists while minimizing unnecessary expenses.

China’s rapid urban development and a maturing cultural interest in the arts paved the way for UAP to make its mark on the industry and the country, through what managing director Steven Shen refers to as catching the right wave.

Florentijn Hofman, Kraken, 2017, Shenzen, China. Courtesy of UAP.

Back in 2008, “the business was so unique compared to the majority of what we were seeing,” Shen said of his first encounter with the Tobins, back when he was working at the Queensland Government China Trade Office. “When Matt Tobin came to my office to discuss how they could expand into China, after half an hour I still couldn’t figure out how we could help him. He talked a lot about art, artists, and urban development…it was so rare, 10 years ago.”

Since then, it’s become essential to the development of the market. “The integration of art into a broader business strategy is going to be really important going forward,” Shen elaborated, reflecting on the growth UAP has seen in its business, and in its clients’ approaches to a wide range of projects. With the availability of selfie-consultants these days, and a growing interest in technology like augmented reality, it’s clear to Shen and his team that the future of urban development, especially in China, lies in the arts. And UAP might be in just the right place to drive that conversation.

The way the company has developed within the PRC speaks not only to its business acumen, but to the notion that “Made in China” can be a testament to quality, and not simply affordable manufacturing.

New York’s Public Art Fund chose to develop a continuing partnership with UAP after it offered to cover the initial cost of Ai Weiwei’s work, and due to its proven commitment to high-quality production.

It’s become clear that UAP is investing not only in its collaborators, but in the future of public art.

Sarah Forman

No comments:

Post a Comment