Why Clement Greenberg Defaced David Smith’s Sculptures

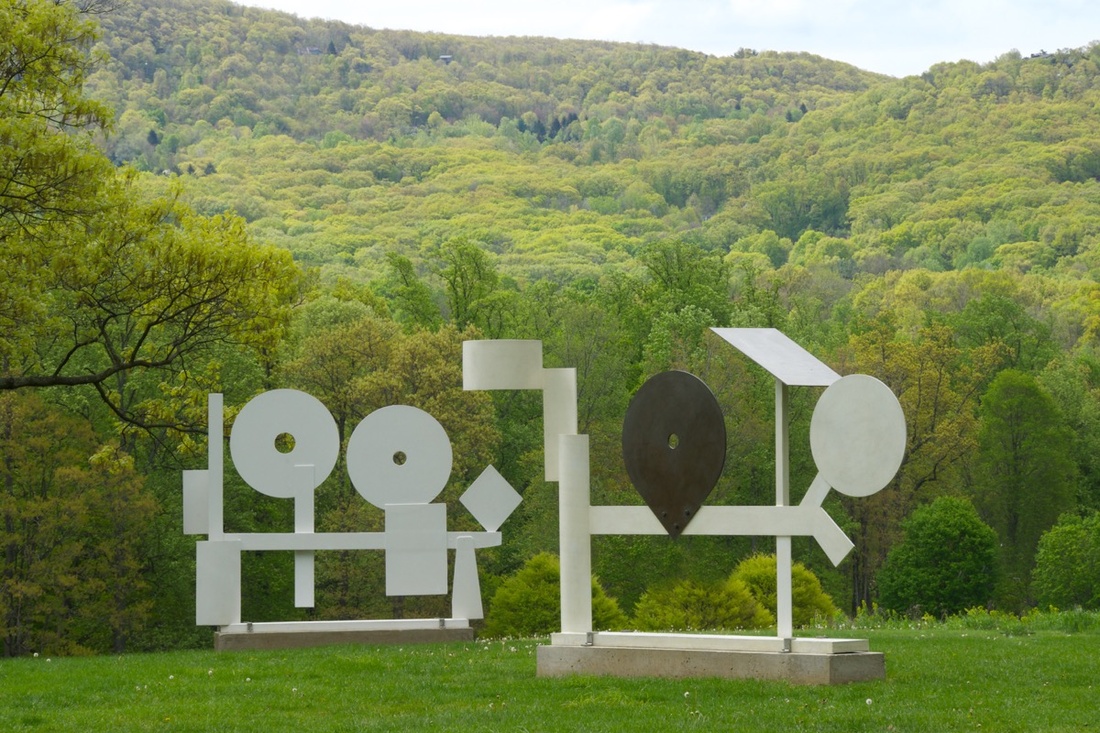

David Smith, Primo Piano I, 1962. Courtesy of The Estate of David Smith, New York, and Hauser & Wirth. © The Estate of David Smith/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo by Jerry I. Thompson, courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

David Smith, Primo Piano I, 1962. Courtesy of The Estate of David Smith, New York, and Hauser & Wirth. © The Estate of David Smith/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo by Jerry I. Thompson, courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

Clement Greenberg, arguably the most influential art critic of the 20th century, never liked David Smith’s painted sculptures.

Although he was a dedicated advocate of the American artist’s work, Greenberg believed that Smith’s use of color (as in all mid-century modernist sculpture) was problematic. “I don’t think he has ever used applied color with real success,” he wrote. In 1951, the critic went so far as to ask Smith’s permission to repaint a multicolored sculpture the artist had gifted him.

“It should be black,” Greenberg wrote in a letter. “We can always scrape it off again.” (The artist’s reply, if there was one, has never come to light.)

Then, in 1965, Smith died unexpectedly in a car crash. He was 59 years old, at the peak of his artistic career. Greenberg was named as an executor of his estate, along with artist Robert Motherwell and lawyer Ira Lowe. They were left to tend to Smith’s 80 acres at Bolton Landing—a parcel of land in the Adirondacks where Smith lived, worked, and displayed his pioneering welded-metal sculptures.

David Smith, 2 Circles 2 Crows, 1963. Private Collection, Florida. © The Estate of David Smith/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo by Jerry I. Thompson, courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

David Smith, 2 Circles 2 Crows, 1963. Private Collection, Florida. © The Estate of David Smith/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo by Jerry I. Thompson, courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

Years passed, and photographer Dan Budnik, who had befriended Smith a few years before his death, returned to Bolton Landing again and again to document the sculptures lining the fields. Sometimes these were silhouetted against snowdrifts, other times against a clear blue summer sky. In 1974, however, Budnick realized that more than the backgrounds were changing—a handful of sculptures had been deliberately altered.

He brought photographic proof to Art in America, which enlisted art critic Rosalind Krauss, then an associate art history professor at Hunter College, to write an accompanying essay. Her story would send shock waves through the art world, launching a contentious debate about the primacy of an artist’s intention.

As Krauss reported in the magazine’s September/October issue, several sculptures, originally white, had been “deliberately stripped of paint,” while others were simply left to flake in the sun without proper maintenance.

“Given the identity of the executors of the estate, all this becomes particularly disturbing,” she wrote. “These pieces reveal an impairment of the integrity of the oeuvre of a major artist, an aggressive act against the sprawling, contradictory vitality of his work as Smith himself conceived it—and left it.”

Installation view of work by David Smith. Courtesy of The Estate of David Smith, New York, and Hauser & Wirth. © The Estate of David Smith/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo by Jerry I. Thompson, courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

Installation view of work by David Smith. Courtesy of The Estate of David Smith, New York, and Hauser & Wirth. © The Estate of David Smith/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo by Jerry I. Thompson, courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

Greenberg took sole responsibility for the changes, stating that the sculptures were unfinished and their surfaces in bad condition. By stripping the paint, allowing them to rust, and then varnishing them, the critic argued that he had returned them to a more authentic state. (Smith had been known to leave sculptures outside through the winter, in order to achieve a particular level of rusting.) “Smith would hate to know that those seven sculptures stayed covered with alkyd white,” Greenberg claimed in 1978, citing his two-decade friendship with the artist.

There was an outpouring of opinion from historians, artists, dealers, and curators alike. Their responses appeared in the pages of Art in America and the New York Times—a debate, notes art historian Sarah Hamill, that hinged on the assumption that the white paint was simply a primer. Some agreed with Greenberg, that a temporary coat was less true to Smith’s intention than raw steel. Others argued that Smith’s artistic process itself should be preserved.

As sculptor Beverly Pepper wrote in Art in America in 1975, “Should we not value phases of an artist’s research as much as the conclusions he came to?”

David Smith, Primo Piano II, 1962. Courtesy of The Estate of David Smith, New York, and Hauser & Wirth. © The Estate of David Smith/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo by Jerry I. Thompson, courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

David Smith, Primo Piano II, 1962. Courtesy of The Estate of David Smith, New York, and Hauser & Wirth. © The Estate of David Smith/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo by Jerry I. Thompson, courtesy of Storm King Art Center.

In the end, white won out. His reputation tarnished, Greenberg resigned from the estate in 1979 and eventually apologized for his actions. Smith’s daughters took over, repainting the sculptures so they looked as they did when the artist died. This summer, five of these works are on view at Storm King Art Center, in upstate New York, as part of the exhibition “David Smith: The White Sculptures.”

But in the decades following the controversy, historians have wondered if perhaps Smith viewed white as more than a primer. According to Storm King curator Nora Lawrence, Smith said he applied up to 25 coats of paint to several of these works. “He had worked at a Studebaker factory in the 1920s, so he would say ‘I think that’s actually [more coats] than a Chevrolet,’” she said.

And these sculptures were white for several years before Smith’s death, Lawrence adds. “He was living with them like that,” she said. “It’s not completely clear that they were necessarily going to always remain white, that that was his final intention for them. But it is clear that he was interested in them.”

—Abigail Cain

No comments:

Post a Comment