Why Sculptor Flora Mayo Was Written Out of Art History

Film still from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Flora, 2017. Courtesy of the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

Film still from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Flora, 2017. Courtesy of the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

Alberto Giacometti is remembered by history as a sculptor, not a muse. But one photo, tucked in the artist’s 1985 biography by James Lord, tells a different story. In it, Giacometti sits beside a sculpture of his own head. Next to them is the bust’s maker: Flora Mayo. She looks over her portrait and subject with authority.

If Mayo’s name doesn’t ring a bell, you’re not alone. Until this past May, Lord’s Giacometti biography was one of only a handful of art history books that included her name. There, she’s discussed only in passing—and in blatantly sexist terms. “Flora looks at her lover wistfully, as she had cause to do,” Lord writes, describing the photo of her and Giacometti. “She is attractive but not beautiful, and there is something weak in her face.”

Artist duo Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, however, are setting Mayo’s record straight. Their 30-minute film, Flora (2017), is on view in the 57th Venice Biennale’s Swiss Pavilion through November. For the first time, it uncovers the circuitous, heartbreaking story of Mayo’s life and work, which were both shaped by expectations imposed on women during her lifetime.

Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Bust, 2017. Photo by Ugo Carmeni. Courtesy of the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

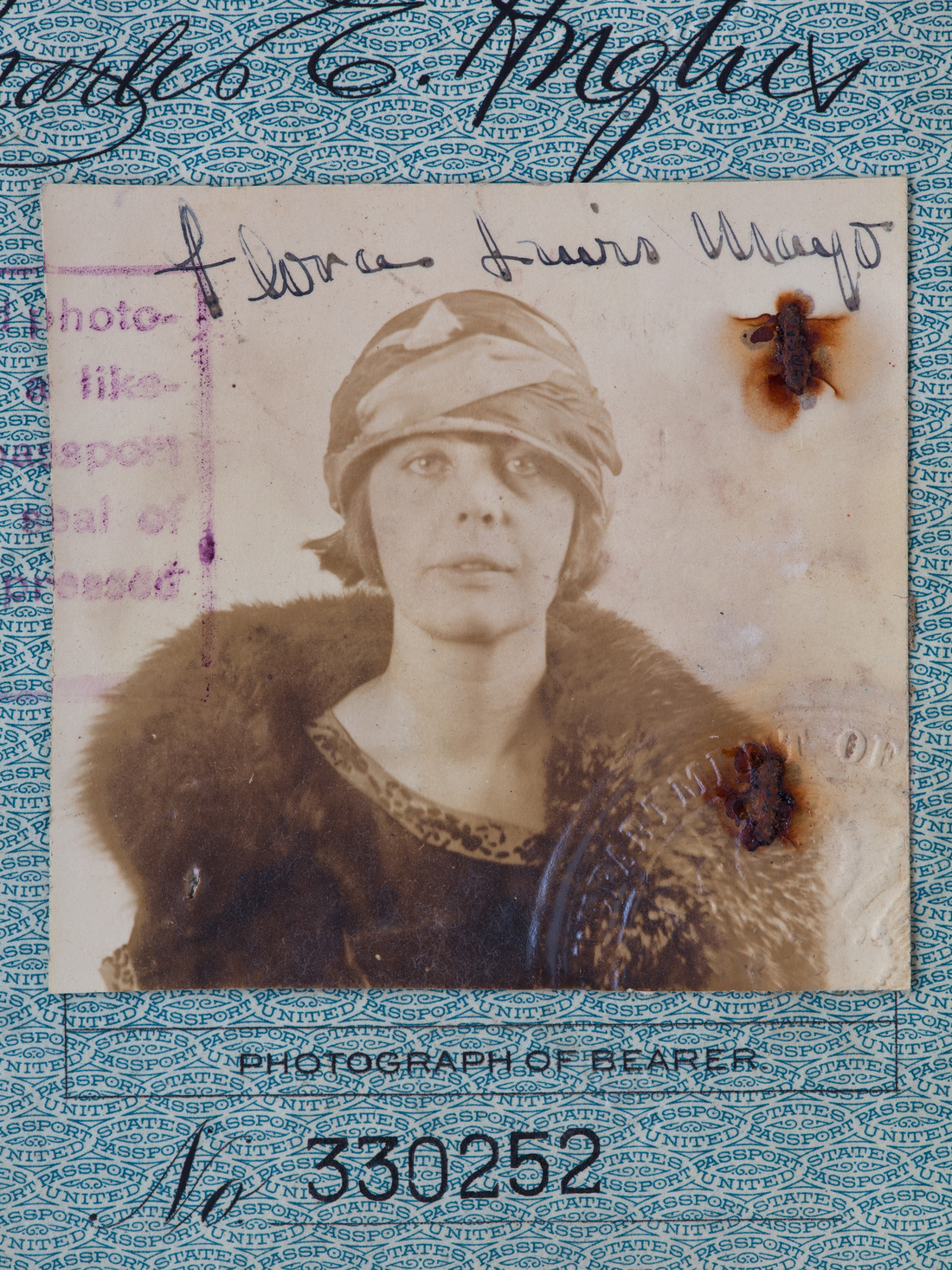

Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Bust, 2017. Photo by Ugo Carmeni. Courtesy of the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin. Production still from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Flora, 2017. Flora Mayo’s passport issued 1923. Courtesy of the Artists and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

Production still from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Flora, 2017. Flora Mayo’s passport issued 1923. Courtesy of the Artists and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

Hubbard and Birchler have long been inspired by the forgotten histories of the places they encounter. They began their Biennale project by researching Giacometti’s insistent refusal to represent Switzerland in Venice during his lifetime. But while reading his biography, it was the “sexist, brief mention of Mayo,” says Hubbard, that that stuck with them. Curiosity piqued, they embarked on an exhaustive effort to uncover the details of the forgotten artist’s life.

Lord’s text filled in some of her biographical details. Mayo was born in Denver to a wealthy family and was a free spirit from a young age. Her conservative teachers and family weren’t pleased: “You’re the kind of girl at whom the devil looks up from hell and says, ‘I want you down here,’” scolded one headmistress.

In an attempt to subdue Mayo, her family pushed her into a marriage to a man she didn’t love. Stifled, she escaped to New York and began taking classes at the Art Students League. At 25, she landed in Paris, rented a studio, began making sculptures, and befriended Giacometti, a fellow student at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere. Later, they became lovers. She called him “Jack;” he called her “the American.”

Film still from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Flora, 2017. Courtesy of the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

Film still from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Flora, 2017. Courtesy of the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

Lord’s account revealed little more than this. Big questions lingered for Hubbard and Birchler: Where did the rest of Mayo’s life take her? And where was her art? When other art history tomes proved useless, they turned to shipping and ancestry logs, census and housing records, and local newspaper accounts.

It wasn’t until Birchler made a “crucial research discovery,” says Hubbard, that they were able to flesh out Mayo’s story. The missing puzzle piece was Mayo’s son, David. He knew a different side of his mother that transpired after she left Paris, set her art aside, and made a new life in California. It was David who would become the subject of Flora.

“No one has ever contacted me wanting to know about my mother, Flora, ever,” says David, now 81, in the film’s opening moments. He was shocked when Hubbard and Birchler reached out to him, but an exchange began: The artists explained to David what they knew of Mayo’s life in Paris, and David what he knew of Mayo in her later years.

Flora weaves together these two distinct existences: in Paris, as an artist; and in California, as a mother and factory worker. The two-channel video is projected on opposing sides of a large screen that hangs in the Swiss Pavilion. On one side of a large screen, we see a fictional reimagining of Flora in the happy, confident throes of creating Giacometti’s bust. An actress portrays a young, lovely Mayo careening around her studio, studying her muse and building her sculpture.

Film still from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Flora, 2017. Courtesy of the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

Film still from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Flora, 2017. Courtesy of the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

On the other side of the screen, a tender interview with David unfolds, as he recounts Mayo’s later years, and struggle to support her son. David flips through photos of Flora. “My mother mentioned when I was a young person that she had a friend by the name of Giacometti,” he says. “I didn’t relate to that at all.”

It’s one of several moments in the film that emphasizes the sharp distinction between Mayo’s time in France and her years in the U.S. She was forced to leave Paris after her parents cut her off, so she returned to the states without money—and without her art. “She never told me anything other than she could not afford to bring the works that she produced home,” recalls David. “And I was never curious about what she did with them.”

After returning to the United States in the early 1930s and becoming pregnant with David (he never knew his father), Mayo quit artmaking. She worked as a turret lathe operator in a factory during World War II, and later as a janitor. But while she rarely spoke with David about her past life, she still longed for it.

As the film comes to a close, David recounts his mother’s last years. When he was 26, Mayo scrounged enough money together to go back to Paris by herself. The experience was disappointing; by that point, her friends were long gone. “I think perhaps she was living a little bit of a fantasy and found out that it was unrewarding,” David recalls. Not long after, Mayo headed back to the United States and lived out the remainder of her days in a building in Los Angeles called—seemingly by no accident—Versailles.

Film still from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Flora, 2017. Courtesy of the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

Film still from Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler, Flora, 2017. Courtesy of the artists, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York and Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.

Flora is the story of a woman whose dreams of becoming an artist were thwarted, but whose unbridled independence buoyed not only her own life, but that of her child. It’s not the film that Hubbard and Birchler set out to make, but pursuing unexpected storylines that emerge during their research is part of their process. “What’s important for us is curiosity in the seemingly mundane,” Birchler says, “and that our work continuously engages us in a journey in which we don’t know how, or where, it will end up.”

That journey’s resonance will come to fruition later this summer, when Hubbard and Birchler will bring David and his wife to Venice to see Flora. David never liked Lord’s description of his mother in Giacometti's biography. “[Lord is] totally ignoring her fortitude, that strength when she lost everything, and was doing her best to raise her son,” he says in the film.

With Flora, David will see his mother’s history rewritten—and at least some of her artwork come back to life.

—Alexxa Gotthardt

No comments:

Post a Comment