Art World

Is Getting an MFA Worth the Price?

When you crunch the data on where successful artists went to school, the pattern is striking.

What’s the value of going to art school? The question has become a hot topic of late.

The charge that contemporary art has become over-academic, producing “zombie” art, is not new. “The proverbial romantic artist, struggling alone in a studio and trying to make sense of lived experience, has given way to an alternate model: the university artist, who treats art as a homework assignment,” Deborah Solomon wrote in an article about the MFA boom in the New York Times. That was 1999.

In the 2000s, the MFA was pitched as a Golden Ticket, with an ever more youth-oriented art market generating rumors of dealers snapping up artists right out of school. A degree that was originally designed to allow you to teach became seen as the pathway to a gallery career.

Related: The USC Roski Fiasco Points to the Corrosion of Art Education Nationwide

In more recent years, angst about art school has become entangled with the political debate about student debt’s crushing toll. Art collectives like the Bruce High Quality Foundation have founded their own alternative art schools, while the group BFAMFAPhD seeks to raise awareness about the high number of art students who default on their loans. The Atlantic calls the MFA “an increasingly popular, increasingly bad financial decision.”

Is it?

To try and answer that question, Caroline Elbaor and I created a list of the 500 most successful American artists at auction from artnet’s Price Database,

looking at figures born in 1966 or later. We picked that year because

it gave us a neat 50-year time span, and roughly corresponds to the

beginning of Generation X, essentially a way of getting a snapshot

of the market fortunes, to date, of millennials and the generation

immediately prior.

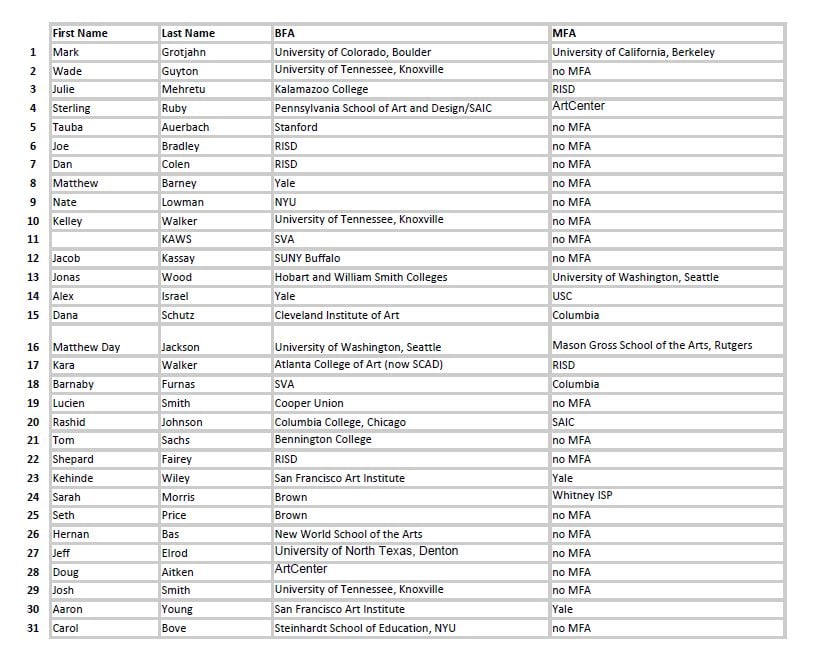

The sample ranges from figures with records in excess of $100 million (Mark Grotjahn, with more than $184 million at auction, or Wade Guyton, with $130 million), down to figures whose fortunes, as measured by this method, are quite modest, with just over $13,000 in career sales at auction.

We tracked down where each artist on the list went to graduate school, either from publicly available sources or by contacting the artists or their representatives. (For a very few, we were unable to find any information; we’ve left their fields blank in the attached table.) With that data in hand, we could then look for patterns as to how educational choices correlate with this measure of early-career success.

Related: Why You Should Be Suspicious of the ‘Creative Economy’

Some caveats, before we look at the results: The secondary market for art is one sign of success, but certainly not the only one. There are artists who make a good living but, for whatever reason, do not create works that are resold at auction. Some artists focus on public or community-based art, or simply don’t create objects. An auction track record simply means that someone thought a particular artist’s work was valuable enough, over time, to resell it.

A second point: Getting your art sold is certainly not the only reason to go to art school. Some artists go to hone their craft, or to learn to communicate their ideas, or to teach, or simply because they need the time to focus on themselves—all fine things.

But if someone is pitching you a career in art, here are some things to think about first.

The Persistence of the Non-Academic Artist

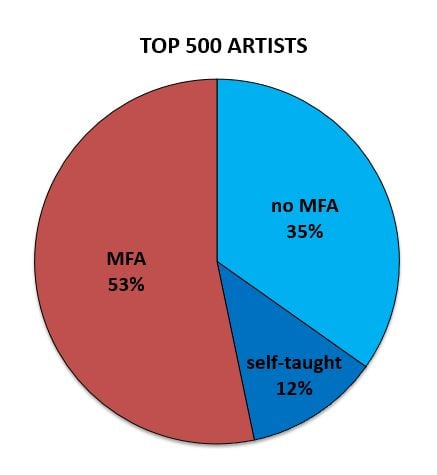

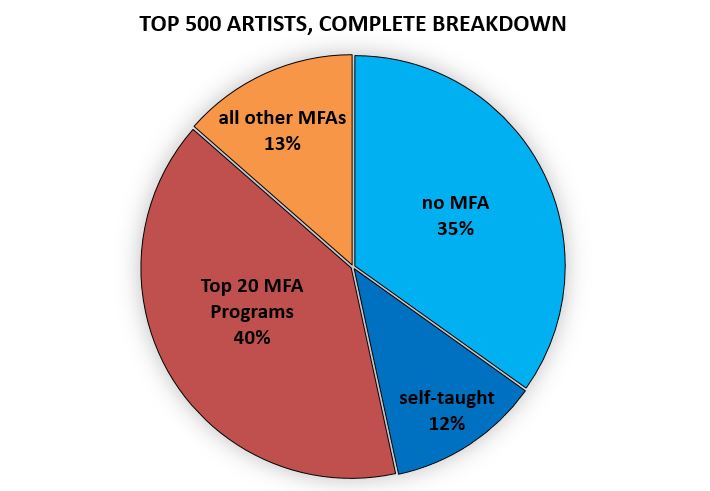

There is hope for those who hate school: Despite the widespread perception that contemporary art is dominated by an MFA mafia, nearly half of the figures on our list of 500 successful early-career artists either did not have an MFA, or didn’t study art academically at all.

Even among the 10 most successful figures, six lack an MFA: Wade Guyton (#2), who “attended,” but did not graduate from Hunter, as far as we can tell; Tauba Auerbach (#6); Joe Bradley (#7); Dan Colen (#8); Matthew Barney (#9); and Nate Lowman (#10).

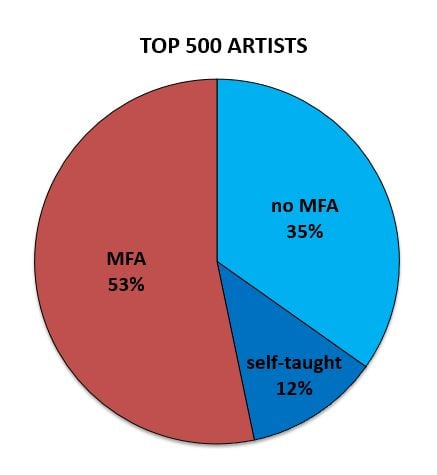

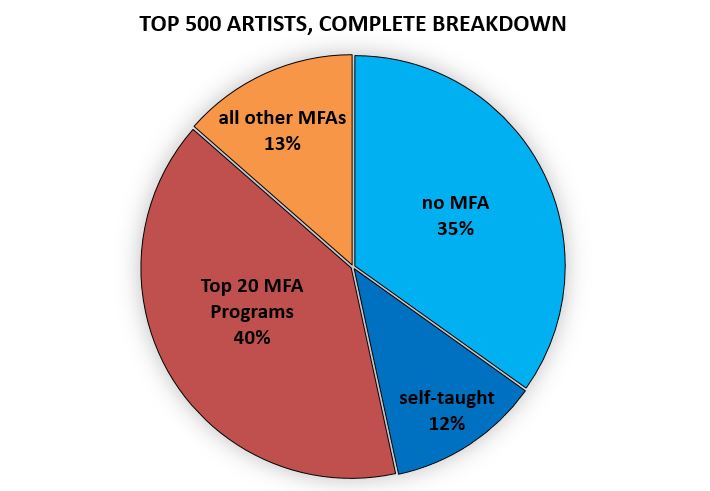

Overall, some 35 percent of artists here have no MFA—and another 12 percent have no degree in art, period. (For our purpose, we counted artists who attended a school but didn’t finish as “self-taught.”)

Something else worth noting: A substantial chunk of the non-academic figures came to attention not through the gallery scene, but through street art: KAWS (#12), RETNA (#55), Chris Johanson (#83), etc. Arguably such figures represent a totally different career path than the one set out by the MFA, with a different set of gatekeepers altogether.

Related: 11 Affordable Art Schools in Art World Centers (and Some Alternatives)

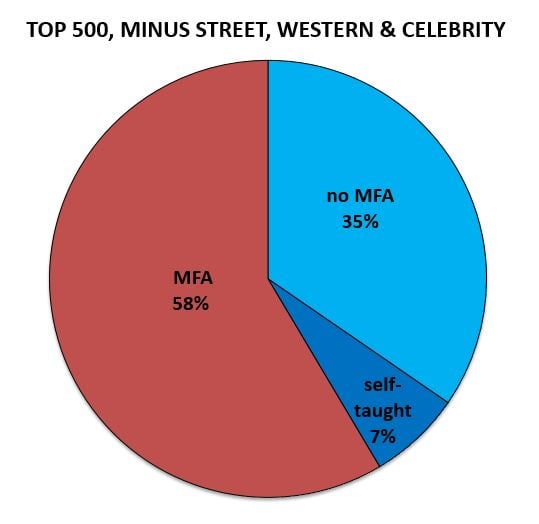

The art scene of the American West, which encompasses figures like Kyle Polzin (#59), Nicholas Coleman (#115), or Logan Hagege (#138), is also something of its own world. And there are a few figures on the list—modern-day Michelangelos such as Adrien Brody (#167), Marilyn Manson (#218), and Kurt Cobain (#277)—who are celebrities first, artists second.

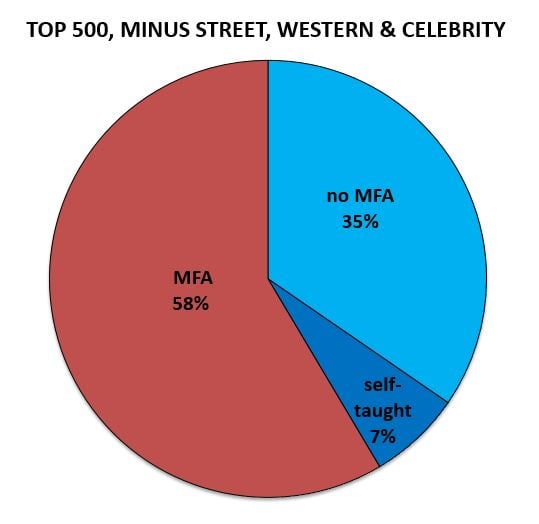

If we subtract such figures, does it change the picture? Excluding from our tally the 52 names that fit these categories does make the “self-taught” approach look like a slightly less viable route to success. In this graph, the MFA-trained artists are more clearly in the majority:

Yet even looking at things this way, over 40 percent of the Top 500 artists did without an MFA or were self-taught, proving that the degree is far from a necessity.

Yale and the “Power Law”

If you can, is it worth going to graduate school for art, though? The answer is fairly clear. Yes—if you go to Yale.

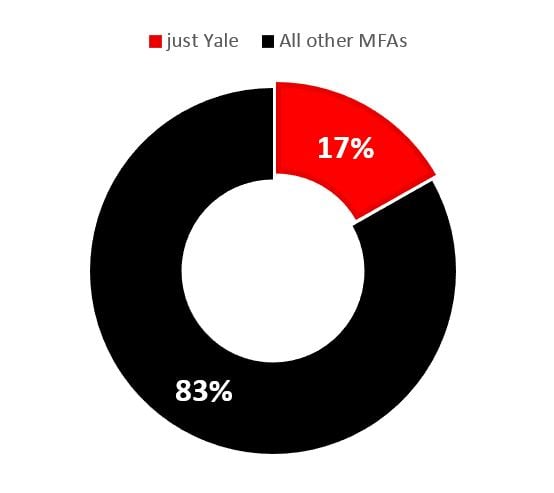

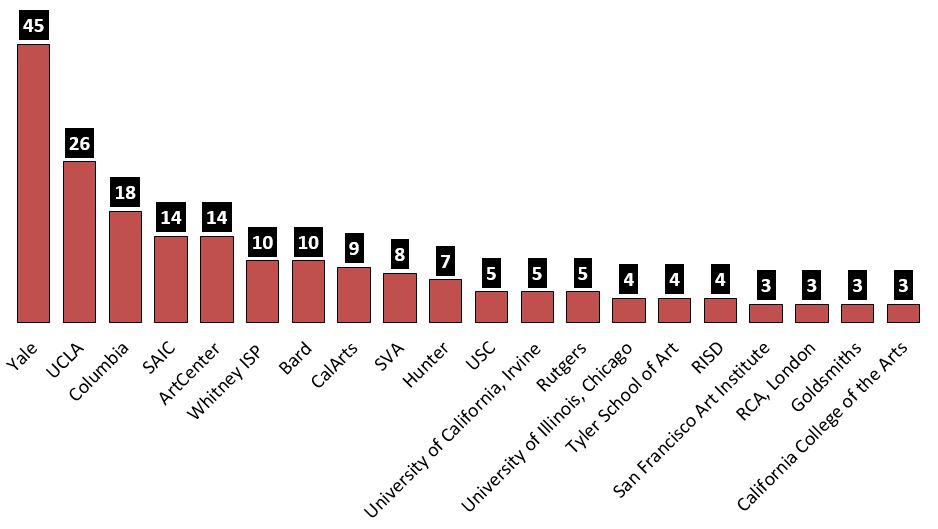

Over this 50-year period, Yale’s Graduate School of Art has pumped out nearly 10 percent of all our successful artists.

Indeed, if you look at the distribution of schools on the list, it follows what statisticians call a “power law”—is has a tall head and a long tail. As one blog on the concept explains, “power law” distributions are ones in which “a small number of outcomes have dramatically higher values than the remaining population.”

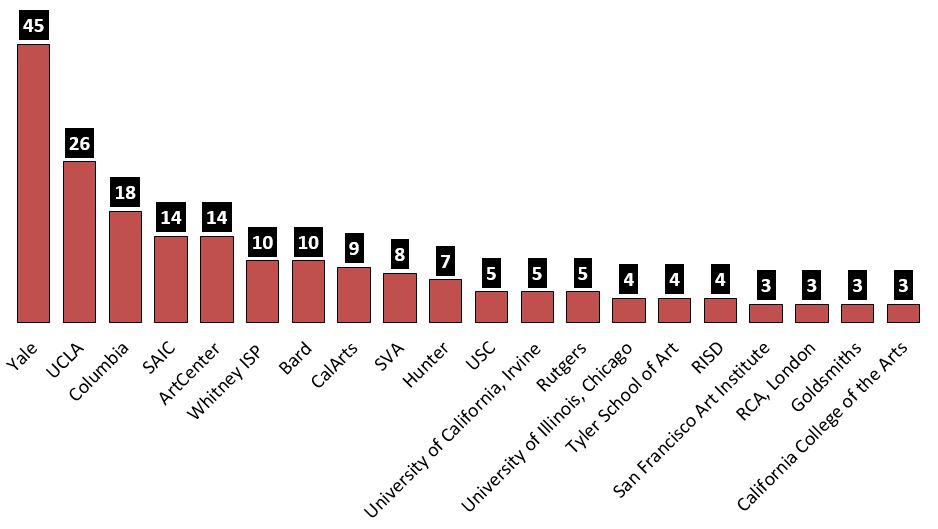

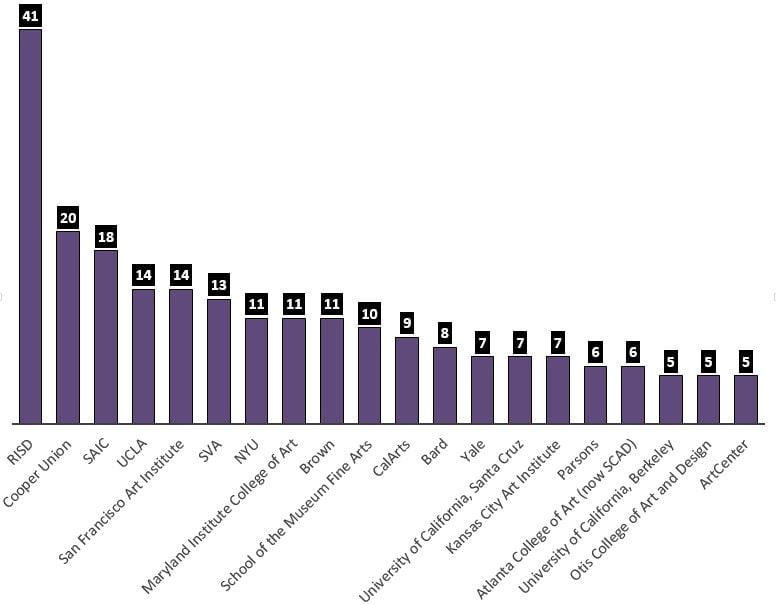

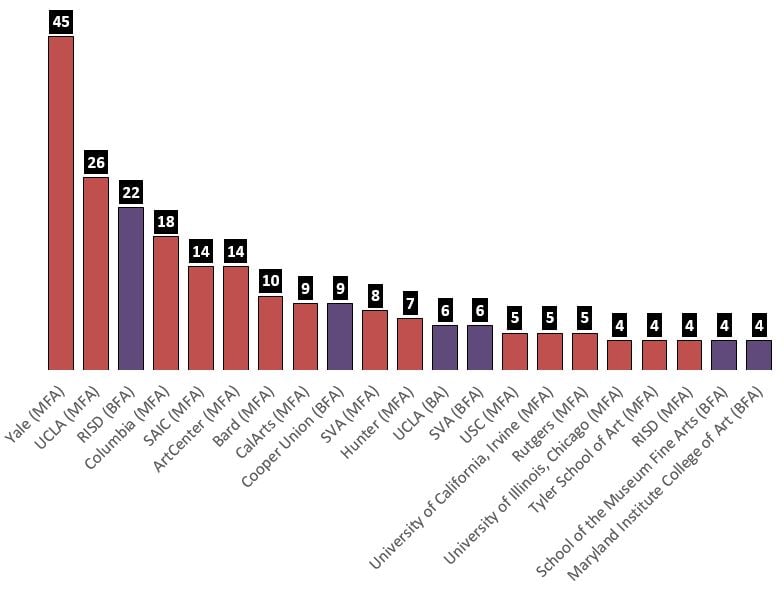

Here is the list of the top 20 MFAs in this sample, with the number of artists holding the credential:

When it comes to art, what this means, practically, is that going to the best school really, really matters—but very quickly the value of any program over any other levels off.

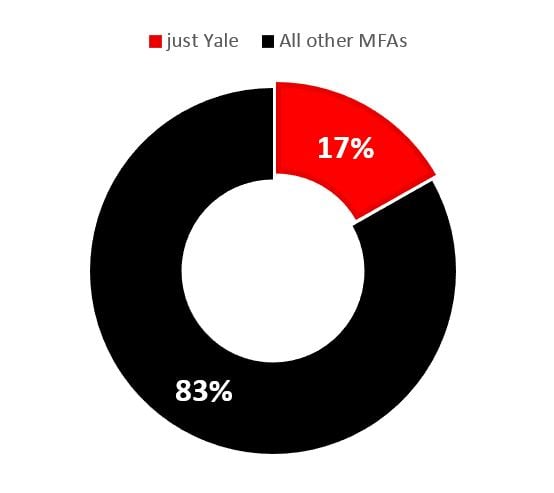

Yale’s weight in this Top 500 is already more than its next two competitors, UCLA and Columbia, combined. Looking just at the MFA-trained artists on this list, a full 17 percent went to Yale.

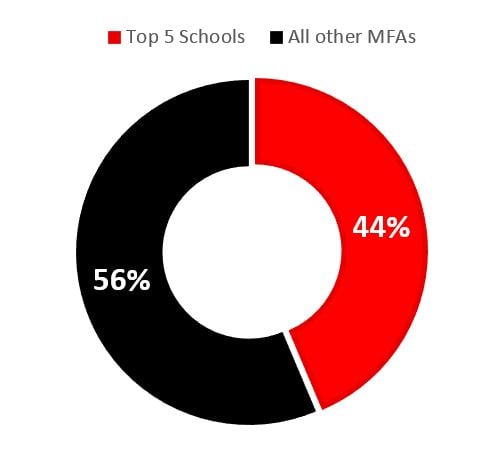

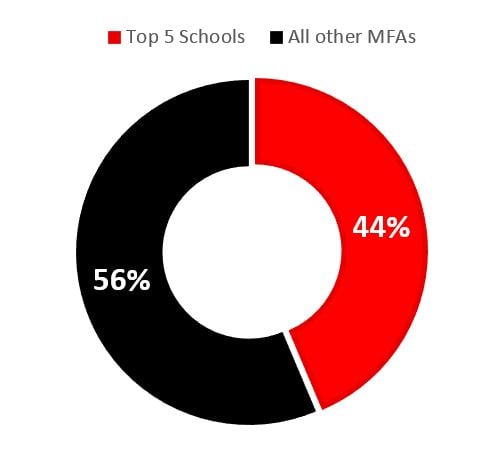

Expanding the selection to look at the Top Five programs, they account for 44 percent of all the MFAs in the Top 500.

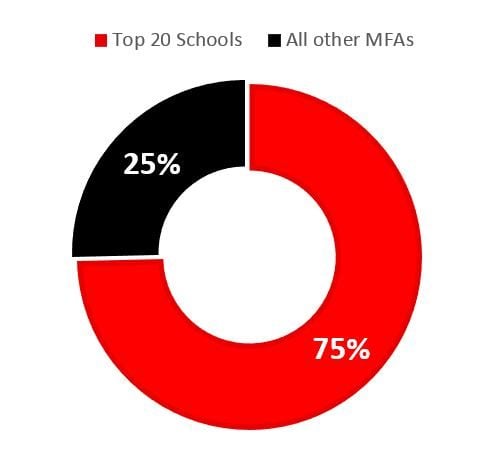

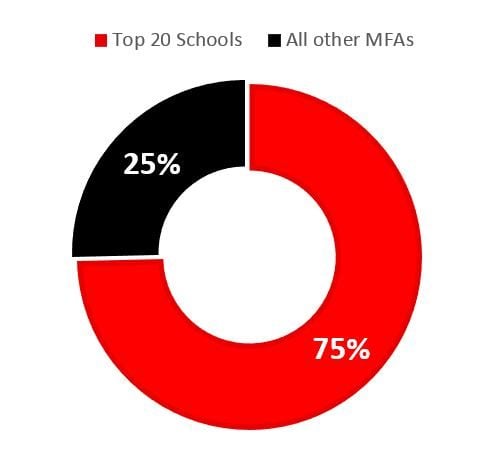

Finally, expanding to the Top 20 schools takes us to 75 percent. That is, of all the artists who got an MFA and went on to the kind of early-career success captured by our Top 500, three quarters went to one of just 20 schools.

Leaving the top 20 graduate programs represented here, you are talking about a large number of schools with no more than two artists on the list—and many, many with only one. That makes these schools’ ability to predict early-career success appear fairly random, since a single sale by an artist from another institution could shake up the ranking.

RISD Rules

We also looked at undergraduate studies.

In general, the data is much fuzzier, and harder to parse (NYU appears in the top, for instance, which is misleading, since artists like Nate Lowman or Carol Bove went there, but not as art students).

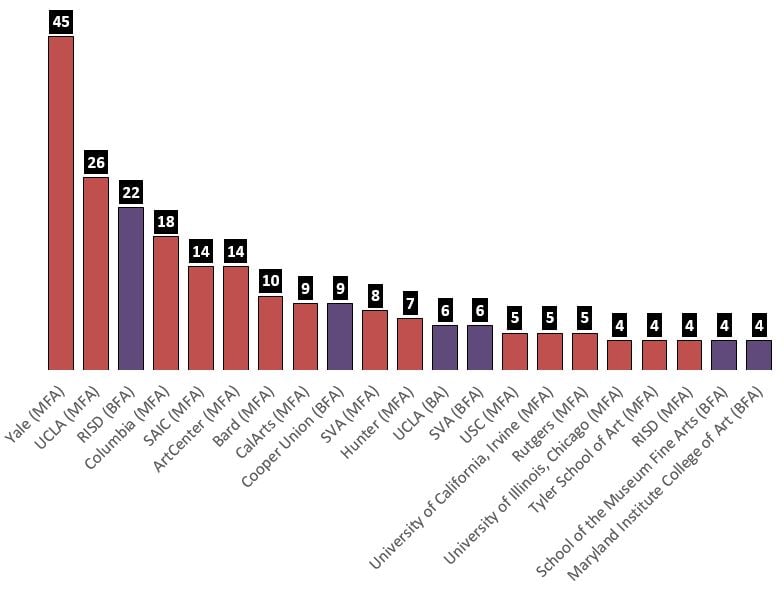

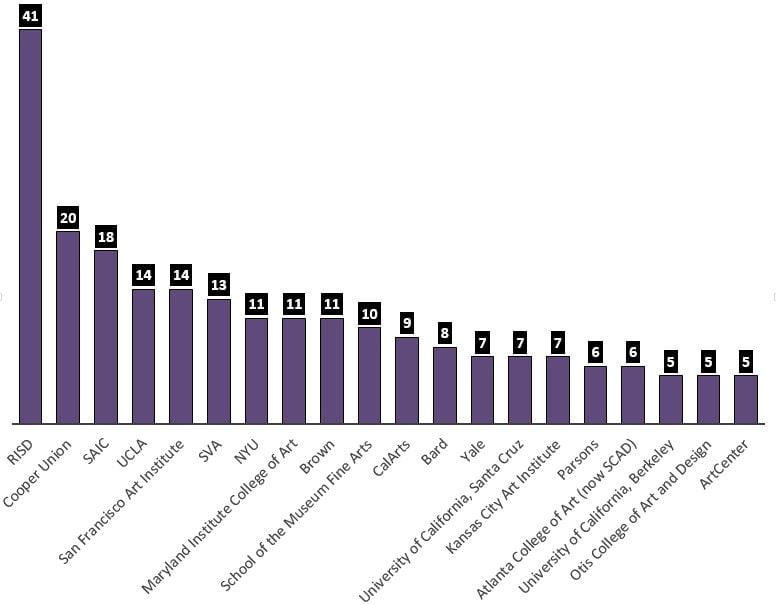

But the results still follow the same “power law” distribution, with the Rhode Island School of Design in the top spot.

Related: Sydney’s Art World Up in Arms Over Plans to Close Art School

Indeed, RISD has more than twice the weight on the list as Cooper Union, its nearest competitor. The School of the Art Institute of Chicago comes in next, followed by UCLA (which eats Yale’s lunch at the undergraduate level) and the San Francisco Art Institute.

Looking deeper, we find 22 artists in the Top 500 list who went to RISD but have no MFA. That makes the RISD undergraduate degree about as predictive of success, here, as an MFA from UCLA, which has 26 figures on the list, and more valuable than an MFA from Columbia, which has 18.

Looking just at the most common terminal degrees on the list, here is what you see:

School Ties

Are there particular combinations of undergraduate and graduate programs that came up over and over again?

The Takeaway

What accounts for the extreme skew towards a few programs?

Perhaps the top schools get the best of a small pool of gifted applicants, and offer resources that allow students to flower in a way that they don’t elsewhere. But are Yale grads really twice as creative as graduates from UCLA? Probably not.

It seems likely that, in art, connections and pedigree open doors, and that the best MFAs signal to dealers and collectors that students are proximate to these status networks, making their art more bankable.

On this level, the value of the MFA as a signal would decline rapidly, since the whole point is to signify that the artists in question belong to an exclusive set. (“Power law” phenomena often occur in fields that follow a “rich-get-richer” pattern.)

The exact proportion of the two factors is hard to reckon without further research.

Looking at the backgrounds of American artists born since 1966, you could sum up a potential lesson of the recent past like this: If you can get into one of the very top programs, it may well give you a better shot at cracking the puzzle of art-career success than going without. Even that decision, though, has to be weighed against the high number of artists who have skipped that step, with the time and expense that it entails.

Outside of those elite brands, though, going to art school becomes a very different kind of choice. It may be worthwhile for a great many artistic reasons, but it does not have a noticeable career-boosting effect, at least not among the first rank of peers. You are essentially following your own path.

Indeed, it looks very much like you could have not gone to school at all, and have been about as likely to capture the attention of the art market.

The charge that contemporary art has become over-academic, producing “zombie” art, is not new. “The proverbial romantic artist, struggling alone in a studio and trying to make sense of lived experience, has given way to an alternate model: the university artist, who treats art as a homework assignment,” Deborah Solomon wrote in an article about the MFA boom in the New York Times. That was 1999.

In the 2000s, the MFA was pitched as a Golden Ticket, with an ever more youth-oriented art market generating rumors of dealers snapping up artists right out of school. A degree that was originally designed to allow you to teach became seen as the pathway to a gallery career.

Related: The USC Roski Fiasco Points to the Corrosion of Art Education Nationwide

In more recent years, angst about art school has become entangled with the political debate about student debt’s crushing toll. Art collectives like the Bruce High Quality Foundation have founded their own alternative art schools, while the group BFAMFAPhD seeks to raise awareness about the high number of art students who default on their loans. The Atlantic calls the MFA “an increasingly popular, increasingly bad financial decision.”

Is it?

A

picture taken on January 26, 2016 shows a visitor walking past an

ancient Roman marble statue at Rome’s Capitoline Museum on Capitol

Hill. Courtesy of FILIPPO MONTEFORTE/AFP/Getty Images.

The sample ranges from figures with records in excess of $100 million (Mark Grotjahn, with more than $184 million at auction, or Wade Guyton, with $130 million), down to figures whose fortunes, as measured by this method, are quite modest, with just over $13,000 in career sales at auction.

We tracked down where each artist on the list went to graduate school, either from publicly available sources or by contacting the artists or their representatives. (For a very few, we were unable to find any information; we’ve left their fields blank in the attached table.) With that data in hand, we could then look for patterns as to how educational choices correlate with this measure of early-career success.

Related: Why You Should Be Suspicious of the ‘Creative Economy’

Some caveats, before we look at the results: The secondary market for art is one sign of success, but certainly not the only one. There are artists who make a good living but, for whatever reason, do not create works that are resold at auction. Some artists focus on public or community-based art, or simply don’t create objects. An auction track record simply means that someone thought a particular artist’s work was valuable enough, over time, to resell it.

A second point: Getting your art sold is certainly not the only reason to go to art school. Some artists go to hone their craft, or to learn to communicate their ideas, or to teach, or simply because they need the time to focus on themselves—all fine things.

But if someone is pitching you a career in art, here are some things to think about first.

The Persistence of the Non-Academic Artist

There is hope for those who hate school: Despite the widespread perception that contemporary art is dominated by an MFA mafia, nearly half of the figures on our list of 500 successful early-career artists either did not have an MFA, or didn’t study art academically at all.

Even among the 10 most successful figures, six lack an MFA: Wade Guyton (#2), who “attended,” but did not graduate from Hunter, as far as we can tell; Tauba Auerbach (#6); Joe Bradley (#7); Dan Colen (#8); Matthew Barney (#9); and Nate Lowman (#10).

Overall, some 35 percent of artists here have no MFA—and another 12 percent have no degree in art, period. (For our purpose, we counted artists who attended a school but didn’t finish as “self-taught.”)

Something else worth noting: A substantial chunk of the non-academic figures came to attention not through the gallery scene, but through street art: KAWS (#12), RETNA (#55), Chris Johanson (#83), etc. Arguably such figures represent a totally different career path than the one set out by the MFA, with a different set of gatekeepers altogether.

Related: 11 Affordable Art Schools in Art World Centers (and Some Alternatives)

The art scene of the American West, which encompasses figures like Kyle Polzin (#59), Nicholas Coleman (#115), or Logan Hagege (#138), is also something of its own world. And there are a few figures on the list—modern-day Michelangelos such as Adrien Brody (#167), Marilyn Manson (#218), and Kurt Cobain (#277)—who are celebrities first, artists second.

If we subtract such figures, does it change the picture? Excluding from our tally the 52 names that fit these categories does make the “self-taught” approach look like a slightly less viable route to success. In this graph, the MFA-trained artists are more clearly in the majority:

Yet even looking at things this way, over 40 percent of the Top 500 artists did without an MFA or were self-taught, proving that the degree is far from a necessity.

Yale and the “Power Law”

If you can, is it worth going to graduate school for art, though? The answer is fairly clear. Yes—if you go to Yale.

Over this 50-year period, Yale’s Graduate School of Art has pumped out nearly 10 percent of all our successful artists.

Indeed, if you look at the distribution of schools on the list, it follows what statisticians call a “power law”—is has a tall head and a long tail. As one blog on the concept explains, “power law” distributions are ones in which “a small number of outcomes have dramatically higher values than the remaining population.”

Here is the list of the top 20 MFAs in this sample, with the number of artists holding the credential:

When it comes to art, what this means, practically, is that going to the best school really, really matters—but very quickly the value of any program over any other levels off.

Yale’s weight in this Top 500 is already more than its next two competitors, UCLA and Columbia, combined. Looking just at the MFA-trained artists on this list, a full 17 percent went to Yale.

Expanding the selection to look at the Top Five programs, they account for 44 percent of all the MFAs in the Top 500.

Finally, expanding to the Top 20 schools takes us to 75 percent. That is, of all the artists who got an MFA and went on to the kind of early-career success captured by our Top 500, three quarters went to one of just 20 schools.

Leaving the top 20 graduate programs represented here, you are talking about a large number of schools with no more than two artists on the list—and many, many with only one. That makes these schools’ ability to predict early-career success appear fairly random, since a single sale by an artist from another institution could shake up the ranking.

RISD Rules

We also looked at undergraduate studies.

In general, the data is much fuzzier, and harder to parse (NYU appears in the top, for instance, which is misleading, since artists like Nate Lowman or Carol Bove went there, but not as art students).

But the results still follow the same “power law” distribution, with the Rhode Island School of Design in the top spot.

Related: Sydney’s Art World Up in Arms Over Plans to Close Art School

Indeed, RISD has more than twice the weight on the list as Cooper Union, its nearest competitor. The School of the Art Institute of Chicago comes in next, followed by UCLA (which eats Yale’s lunch at the undergraduate level) and the San Francisco Art Institute.

Looking deeper, we find 22 artists in the Top 500 list who went to RISD but have no MFA. That makes the RISD undergraduate degree about as predictive of success, here, as an MFA from UCLA, which has 26 figures on the list, and more valuable than an MFA from Columbia, which has 18.

Looking just at the most common terminal degrees on the list, here is what you see:

School Ties

Are there particular combinations of undergraduate and graduate programs that came up over and over again?

You might expect the RISD/Yale path to dominate, and there are indeed three figures who followed it: David Benjamin Sherry (#215), Adam Helms (#224), and Schandra Singh (#460).

For what it’s worth, though, several combinations

of schools actually had a higher representation in the Top 500,

occurring four times each:

- School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston to Yale, a path followed by Kristin Baker (#58), Nathan Carter (#297), Laurel Nakadate (#331), and Justin Lieberman (#336).

- San Francisco Art Institute to Yale, the path of Kehinde Wiley (#24), Aaron Young (#31), Iona Rozeal Brown (#203), and Evan Nesbit (#404).

- RISD to CalArts, the path of Laura Owens (#46), Tomory Dodge (#90), Carter Mull (#398), and Brett Cody Rogers (#423).

The Takeaway

What accounts for the extreme skew towards a few programs?

Perhaps the top schools get the best of a small pool of gifted applicants, and offer resources that allow students to flower in a way that they don’t elsewhere. But are Yale grads really twice as creative as graduates from UCLA? Probably not.

It seems likely that, in art, connections and pedigree open doors, and that the best MFAs signal to dealers and collectors that students are proximate to these status networks, making their art more bankable.

On this level, the value of the MFA as a signal would decline rapidly, since the whole point is to signify that the artists in question belong to an exclusive set. (“Power law” phenomena often occur in fields that follow a “rich-get-richer” pattern.)

The exact proportion of the two factors is hard to reckon without further research.

Looking at the backgrounds of American artists born since 1966, you could sum up a potential lesson of the recent past like this: If you can get into one of the very top programs, it may well give you a better shot at cracking the puzzle of art-career success than going without. Even that decision, though, has to be weighed against the high number of artists who have skipped that step, with the time and expense that it entails.

Outside of those elite brands, though, going to art school becomes a very different kind of choice. It may be worthwhile for a great many artistic reasons, but it does not have a noticeable career-boosting effect, at least not among the first rank of peers. You are essentially following your own path.

Indeed, it looks very much like you could have not gone to school at all, and have been about as likely to capture the attention of the art market.

—Research by Caroline Elbaor.

Follow artnet News on Facebook.

Share

Article topics

No comments:

Post a Comment