Looming Crisis Can Crash Europe’s Banks

euconedit

You may also like

As I explained in my two recent articles about the French government’s budget problems, there is a significant risk that the second-largest economy in the euro zone sinks into a full-scale debt crisis. Last time that happened in Europe, it had major repercussions for the financial institutions—banks—that owned large amounts of low-credit, high-risk government debt.

Now that Europe is about to repeat the last big economic crisis, there is an elevated risk for another bank meltdown.

Before we get to the numbers that suggest an imminent debt-and-bank crisis, let me first recap exactly where Europe is today. Almost every member of the European Union has built a large welfare state that gobbles up two-thirds or more of all government spending. It is this very spending that creates perennial fiscal problems, yet cutting welfare state benefits beyond cosmetic measures has proven to be an insurmountable task for Europe’s elected officials.

The welfare state’s combination of work-discouraging social benefits and growth-discouraging taxes has weighed heavily on the European economy for decades; so far, it has led to two fiscal crises:

- The one in the early 1990s, which was mild by comparison but broke the back of, e.g., the British and Swedish economies; and

- The Great Recession that started in late 2008.

In both these crises, there were repercussions for the financial sector, but the exposure to bad-credit government debt was much bigger in 2008 than 15-20 years earlier. Therefore, the European Central Bank, ECB, had to intervene and save Europe’s financial system; the ultimate goal was to save the euro, a goal that had many absurd consequences that I cannot list here.

In response to runaway credit problems among euro-zone governments, the European Central Bank launched a program to buy bad-credit government debt, both directly and indirectly through cheap loans to the financial institutions.

The strategy worked. It was costly, and it disrupted essential components of the free-market economy, but it confined government defaults to Greece. Pressured by the ECB, among others, Athens unilaterally declared that it would no longer honor 25% of its debt.

This hit Greece’s lenders hard, especially financial institutions, but thanks to the unending commitment by the ECB (and to a large degree, the IMF), the private banking system itself never collapsed.

We may not be as lucky this time around. To see why, let us go back to the reason why banks failed in the Great Recession: their investments in government debt. When the economic crisis gained full force in 2009, credit-challenged governments across Europe borrowed massive amounts of money—and financial institutions were more than willing to lend a pretty penny. In The Rise of Big Government, pp. 107-109, I give examples of this:

- In 2010, Ireland borrowed €39.5 billion, 59% of it from financial institutions;

- In 2011 and 2012, the Spanish government borrowed €323 billion, with €230 billion, or 71%, coming from financial institutions;

- Facing stressful credit downgrades, in 2010 Portugal borrowed €64 billion; financial institutions sold 55% of that new debt.

Common sense demands an answer to a very simple question: if these governments were being downgraded in terms of credit, then why would financial institutions expose themselves to this extravagant exposure to risk?

The simple answer, again, is that the ECB intervened with giveaway loans to financial institutions, on the explicit or implicit premise that they buy treasury securities from credit-challenged euro zone governments. This procedure cost the ECB dearly in the form of monetary expansion and meant the virtual eradication of returns on sovereign debt. However, it stabilized the financial system and prevented a continent-wide banking meltdown.

We are now entering a similar scenario, but with one important difference: the ECB will go into this crisis with so much money supply already pumped out in the euro zone economy that there will be very little room for money-printing for the same purposes as last time. The amount of euros floating around out there, relative to the euro-zone GDP, is of such dangerous proportions already that only a small salvage program for credit-suffering governments risks a rapid eruption of monetary inflation.

Fortunately, not all European governments are in a situation where they can contribute to a new, major fiscal crisis. To begin with, the indebtedness in the euro zone is unevenly spread out. Figure 1 reports consolidated government liabilities as a share of GDP; the numbers are from 2023, the latest year for which Eurostat has published their liabilities breakdown:

Figure 1

Six countries have a debt-to-GDP ratio above 100%; two-thirds, or 14, of the euro zone’s members are above the constitutionally mandated 60%-of-GDP debt cap.

Most of these countries have a troubling debt trend. From 2020 to 2023,

- Austria’s debt-to-GDP ratio has risen from 91% to 97%;

- Estonia has increased its ratio from 21% to 29%;

- Latvia has gone from 50% to 62%;

- Lithuania is up from 52% to 57%;

- Luxembourg has increased its debt ratio from 27% to 32%;

- Malta is up from 54% to 60%;

- Slovakia has gone from 63% to 73%.

Some euro zone members have eased their debt ratio a little bit, but their positive trends are in no way strong enough to counter the rapid increases in these predominantly smaller member states.

The debt-to-GDP ratio is an acute problem for the euro zone, given that they share the same currency. Last time around, during the Great Recession 15 years ago, the ECB, the IMF, and the EU forced several member states to execute harsh, deficit-fighting but socially crippling austerity measures. The purpose was to save them as euro zone members by aligning their debt ratios with less fiscally wrecked parts of the currency area.

Today, a widespread deterioration of the fiscal situation in multiple euro zone countries would be followed by similar calls for austerity, but far from as harsh. The tolerance for such measures among the general public is far lower, as is the European economy’s ability to absorb tax hikes. This limits the ECB’s ability to impose ‘debt ratio alignment’ measures on euro countries.

It is unlikely that the ECB will lament this very much. In the event of a major crisis, they will have their hands full trying to save the banks—again. Help from the IMF will be much appreciated in order to extend such salvage operations to EU members outside the euro zone. As shown in Figure 2, financial institutions own significant portions of government debt all across the EU:

Figure 2

Sweden, where banks are by far the biggest owners of government debt, has a low debt-to-GDP ratio. However, due to the sagging economy with high unemployment and stagnant private consumption, tax revenue will increasingly fall short of spending in the coming 6-12 months. This will force the incumbent center-right government into a rapid increase of the debt ratio.

With other countries doing the same, the question is who will buy their new debt. If we go back to France for a moment, their debt is owned by two categories of investors—and should therefore expect to have to go to them for more debt:

Figure 3

This structure of debt, or distribution of debt ownership, is the same in most European countries. As a result, they are highly vulnerable to disturbances in either the financial industry or the international economy. This, again, reinforces the point made by Figure 2: when the credit status of excessively indebted governments begins to fall like it did in 2010-2014, Europe will quickly face a banking crisis.

Not all countries have been so irresponsible as to become beholden to foreign lenders and to enter a mutually destructive debt-credit relationship with financial institutions. A small number of EU member states, led by Hungary, have managed to bring in their nations’ households as owners of government debt:

Figure 4

The Hungarian success in encouraging households to invest in government debt is the direct result of intelligent policymaking. A three-step policy reform led to major growth in household ownership of Hungary’s government debt; last year, one million Hungarians had invested in their nation’s sovereign debt.

This, in turn, has given Hungary a drastically different debt structure than, e.g., France:

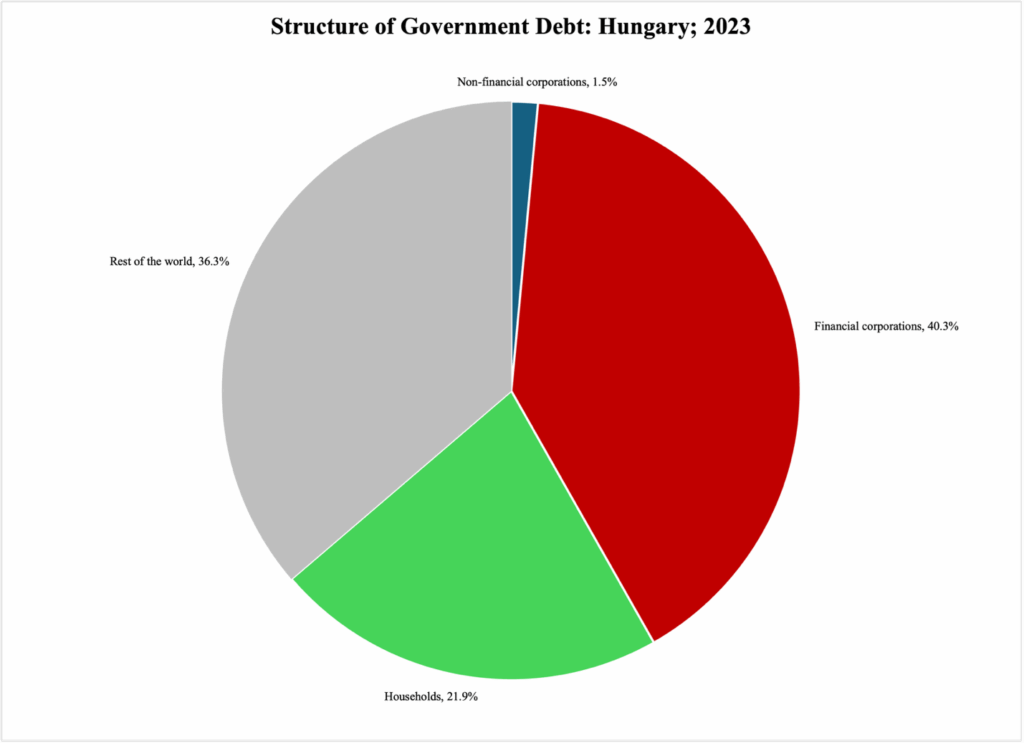

Figure 5

The high household ownership of Hungary’s public debt not only reduces dependency on foreign creditors, but also serves as a good protective coating for the Hungarian banking system if, against all odds, the Hungarian government should be pulled into the next debt storm.

When the next debt storm hits Europe, no country will escape unharmed. However, those who have taken prudent steps to reduce their debt exposure to the rest of the world will stand tall and steady while others fall. Maybe it is time for the rest of Europe to follow Hungary’s example and diversify their debt structures.

- Tags: ECB, economic crisis, euro zone, GDP, government debt, Hungary, IMF, Sven R. Larson, welfare state

No comments:

Post a Comment